Politics is something you feel as well as measure

We can adduce as much statistical evidence as we like for analysis and predictions, but part of politics will always be unquantifiable and subject to judgement

There is a fundamental contradiction in the commentary on and study of politics. If we’re diligent and well-intentioned, we crave facts, data, statistics, hard evidence to understand what’s going on and to support our theories about what has been or what will be, and why. The study of elections in scientific terms is called psephology, from the Greek psephos, or “pebble”, because ancient Athenian juries voted by the jurors using pebbles to indicate their decision, and the term was popularised in the 1950s by the late, great Sir David Butler, a truly remarkable political scientist. (I was lucky enough to see him speak once or twice in Parliament, then in his late 80s or early 90s, and anyone who by then still had tales of Churchill was spellbinding.)

The counterpoint to this relentless appetite for raw information is that politics is as much an art as a science. To take one example, I have often said—I don’t claim it’s an original thought but it’s true—that you will only understand the House of Commons properly if you grasp that it is not just a collection of 650 individual Members of Parliament (of course there are seven Sinn Féin MPs who never take their seats), but also a single organism, which can have moods and instincts and patterns of behaviour. For all that he has been subject to some (largely unfair criticism) recently, one of Sir Lindsay Hoyle’s great strengths as speaker of the House of Commons is that he is usually a very good judge of the feeling of the House, and that, actually, is one of the greatest attributes a speaker can have. His predecessor John Bercow (of whom my views are freely available) was procedurally very knowledgeable and learned, sometimes alarmingly so, but suffered from the blind spot that everything, ultimately, was about him.

This idea that there are currents and trends and directions of travel which cannot be measured or defined is especially true in the period before a general election. It is easy now to see Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 victory as an inevitable part of the story of politics, a turning point at which the old consensus-driven order of the post-war era finally breathed its last and a new broom arrived, transforming the landscape. Certainly, her majority of 44 in the new House of Commons was workable, though it perhaps concealed the extent to which she remained ideologically in a minority in her own cabinet, at least until the major reshuffle of 1981. And she won 44 per cent of the popular vote, to Labour’s 37 per cent, a margin of two million votes, when the two major parties took 608 of the House’s 635 seats.

That said, much about Thatcher was untested. She was the first woman to lead a major political party in Britain, and as late as 1973 she had told a television audience that “I don’t think there will be a woman Prime Minister in my lifetime”. (She was only 47 when she said that.) Her career before 1975, when she became Conservative leader, had been one of diligent application but neither brilliance nor breadth: she had been a minister for pensions and then education secretary, and in opposition had spoken on transport, fuel and power and the economy, and her immediate launchpad to unseating Edward Heath for the leadership was as number two in the shadow Treasury team. Of foreign affairs she had no experience, and had very little profile outside the UK, though the Red Army news sheet Krasnaya Zvezda did her an eternally good turn by dubbing her “the Iron Lady”.

There is also a theory that Jim Callaghan, who had succeeded a clapped-out and perhaps already mentally compromised Harold Wilson as prime minister in the spring of 1976, could have won a general election in the autumn of 1978. By the September of that year, opinion polls suggested a Labour lead, despite the government’s economic difficulties, with unemployment and inflation both falling. This is to an extent a dream sequence for the Left, imagining a renewed Labour mandate, no Thatcherism, SDP split and a 1980s dominated by responsible, moderate socialism. In any event, it was confounded on 7 September 1978, when Callaghan announced there would be no election that year. The Winter of Discontent was yet to arrive.

Callaghan himself was not so sure. Admittedly, he had cause to exonerate himself, but it is worth remembering what he said to Bernard (now Lord) Donoughue, the 44-year-old academic and journalist then running the Number 10 Policy Unit, in the last days of the Labour government in 1979.

There are times, perhaps once every 30 years, when there is a sea change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or what you do. There is a shift in what the public wants and what it approves of. I suspect there is now such a sea change—and it is for Mrs Thatcher.

Some have argued that this was a way of pre-empting personal responsibility for any electoral reverse, and Callaghan was a clever enough politician to have had that in his mind.

(He was a strange mixture of avuncularity, patriotism, decency, conservatism, deep party loyalty, shrewdness, ruthlessness and, when necessary, hard-nosed brutality. He was at that time the only post-war premier other than Churchill, who had attended the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, not to have gone to university and felt it acutely. But, as he reflected: “A lot of people say I’m not clever at all, I’m quite prepared to accept that—except that I became Prime Minister and they didn’t, all these clever people.”)

Nothing in politics is inevitable, but few events are as unforeseen as they sometimes appear. When we think of great political “upsets”, like the Leave victory in the 2016 Brexit referendum, or the Conservative Party’s fourth consecutive election win in 1992, or the Argentinian invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982, there were often in retrospect signs that could have been interpreted differently which would have suggested the outcome which came as a surprise. After Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October last year, I wrote about the way in which Israel had apparently been caught off-guard, and made the obvious comparison with the Yom Kippur War in 1973 when the Jewish state had been equally taken by surprise: after the conflict, the Agranat Commission, chaired by Chief Justice Shimon Agranat, examined the events leading up to the invasion and found that warnings had been overlooked.

In the same way, we are now in a period of politics in which a Conservative victory at the forthcoming general election seems almost impossible. I insert that “almost” not simply because I am a Conservative and am in deep gloom, unwilling completely to surrender to the thought of a Labour government, but because you genuinely can never be sure: when the BBC’s exit poll for the 2015 election declared that the Conservatives would win a majority, Paddy Ashdown, the former Liberal Democrat leader, was dismissive. “If this exit poll is right,” he said, “I will publicly eat my hat.” It was. Alastair Campbell, Tony Blair’s long-time communications guru, was almost as bold about the prediction of SNP support: “I won’t eat my hat, but I will eat my kilt if they get 58 seats”. They won 56.

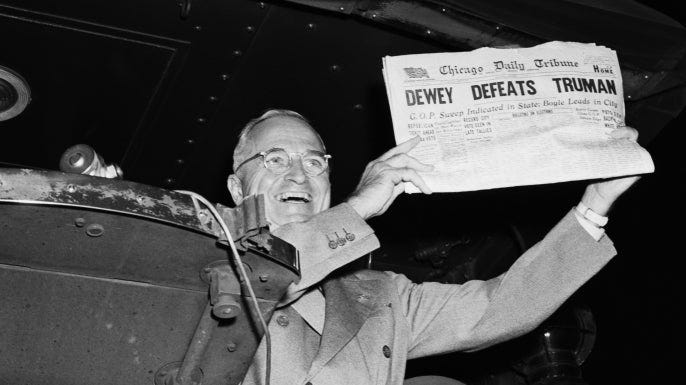

So stranger things have always happened, though I admit I would be struggling to find a historical parallel for what we would have witnessed if the electorate returned a Conservative majority at the election. It would make “Dewey Defeats Truman” look like a statistical margin of error. One can argue about whether the Labour Party’s genuinely extraordinary poll leads will translate into a historic, perhaps unparalleled victory which eclipses the Blair landslide of 1997 and perhaps threatens the very existence of the Conservative Party. The Electoral Calculus website currently translates the polling data into Labour winning 459 seats and a majority of 268, with the Conservatives humiliated on a mere 90 MPs and a Liberal Democrat surge to 49. This would trump even Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative majority of 209 in 1924, the largest for a single party since the Great Reform Act of 1832. Former New Labour strategist John McTernan, talking to Fraser Nelson on Spectator TV this week, cautiously suggested that it was not impossible that Sir Keir Starmer might lead the party to winning 500 seats or more in a House of Commons of 650, again unprecedented in modern times for a single party. In 1997, Tony Blair was one of 418 Labour MPs.

I will say this briefly and I fully admit I cannot “prove” it, and I am perfectly alive to the charge of wishful thinking. I think Labour will probably win, but I don’t think the margin will be as enormous or historic as the figures suggest. I don’t discount the polls or query their accuracy, but I do observe that people can respond one way in an opinion poll and vote another in the privacy of the polling booth. Mainly, though, I base my belief—you can validly call it an instinct or a hunch—on two factors.

The first is that, while the electorate certainly seems both evidentially and anecdotally absolutely done with the current government and very much in the mood for change, I don’t see statistical or anecdotal evidence that they are excited about Starmer’s alternative offering in anything like the way that Blair captured voters’ imagination in the period from 1994 to 1997. New Labour performed a remarkable task of first tacitly guaranteeing the elements of the Thatcherite revolution—in 2002 the former prime minister was asked what she regarded as her greatest achievement, and replied “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds”—while also somehow depoliticising large swathes of politics. There was a sense that Blair’s proposal for public services, the economy, Europe and other issues were the sorts of conclusions any reasonable, moderate person would reach. Throughout 1996 and into 1997, Blair was regularly being rated satisfactorily by half of those polled and achieving positive net approval levels of the order of 15 or 20 points.

By contrast, Sir Keir Starmer’s approval ratings are pretty desperate. Apart from a blip in the summer and autumn of 2022, during the fall of Boris Johnson and the 49-day wonder which was Liz Truss’s premiership, they have been relentlessly negative in net terms since the beginning of 2021, and last month he had a net approval rating of -13. It is certainly true that they are much less negative than the prime minister’s: Rishi Sunak’s approval rating late in March was a monstrous -46. That disparity will probably help power Starmer to a comfortable win and into Downing Street. But let’s be clear about what it also means. When the electorate thinks about Starmer, substantially more people think he’s performing badly than performing well. And this is front of the political equivalent of an open goal.

A survey released in January by UK In A Changing Europe, hardly Conservative cheerleaders, identified this issue. The commentary noted “Whilst public sentiment is anti-Conservative, it is not overwhelmingly pro-Labour”. It pointed out that nearly half of respondents did not know what Starmer stood for, more thought he had said “too little” about what he and a Labour government would do in office, and it concluded, in primly stinging terms, “Focus groups have described the Labour leader in varying terms, from ‘much of a muchness’ to ‘all fur coat, no knickers’.”

In crude terms, I see little evidence that Starmer or his senior colleagues have seduced the electorate. Certainly there is no sense, as there had been with Jeremy Corbyn in 2019, that the Labour leader is a threat to the nation’s economy or security, and, like Blair before him, Starmer seems to have satisfied voters that they can safely vote for him or contemplate his victory. But there is a two-pronged issue, firstly that people don’t really know what a Labour-governed Britain would be like, and, whether they think they know or haven’t given it much thought, they are not positively enthused by the prospect. The pervasive emotion seems to be one of merely longing for relief.

This brings me to my second reason for arguing against an overwhelming Labour victory, or at least for keeping a question mark over it. I fear turnout may be be very low. For decades we had a more than respectable rate of participation in general elections, the numbers never dropping below 70 per cent between 1922 and 1997. In February 1950, just shy of 84 per cent of voters made it to the polling stations. This is far higher than, say, presidential elections in the United States, where the turnout of 62 per cent in 2020 was the highest since Kennedy had (narrowly and dubiously) beaten Nixon in 1960. In 1996, when Bill Clinton won re-election over Republican Bob Dole, more voters stayed at home than voted.

In the UK, we slipped badly when Blair won a second election in 2001. Perhaps it was the culmination of New Labour’s depoliticisation of Britain, but only 59.4 per cent of us went to the polls (I certainly did, marking my paper loyally but hopelessly for Mike Scott-Hayward in North East Fife. He lost by 9,736 to the incumbent Liberal Democrat, Menzies Campbell, for whom I later worked on the UK delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.) The turnout figure has risen at subsequent general elections, and was 67.3 per cent in 2019, but we have still to break back through the 70 per cent barrier (though the turnout for the Brexit referendum in 2016 was 72.2 per cent).

None of this should surprise or baffle. We don’t like politics at the moment, we don’t trust politicians and we have very little faith in the ability of the system to bring about change. Data from the Office for National Statistics published last year showed that only 27 per cent of us trust the government in Whitehall, 24 per cent trust Parliament and 12 per cent trust political parties. (It grieves me slightly that Whitehall beat Westminster, albeit only by three points.) The media came in at 19 per cent. These are pretty poor numbers all round, and even the fact that the civil service (45 per cent) and local government (34 per cent) polled much higher is encouraging only in relative terms.

Ken Livingstone, an easy man to dislike, published a tract in 1987 called If Voting Changed Anything They’d Abolish It. It was not a Livingstone coinage: the Lithuanian anarchist Emma Goldman once said “If voting changed anything, they’d make it illegal”, and a similar sentiment, “If voting made a difference, they wouldn’t let us do it”, is attributed to Mark Twain (but then, what isn’t?). It was an odd expression, perhaps, for Livingstone to articulate in 1987, as he was elected to the House of Commons for Brent East that year, following the deselection of Reg Freeson in what was dubbed “political murder”. But it’s a phrase I’ve always hated, because it has a smug, knowing nihilism about it. If voting doesn’t change anything, what’s your proposed alternative?

It is, however, pervasive as well as corrosive. That phrase the UK In A Changing Europe cites, “much of a muchness”, seems bland but it can be devastating. If significant portions of the electorate simply don’t think it will matter whether they vote or not, they probably won’t, because we all have other things to do on a particular Thursday than go to a church hall or school gymnasium and queue up to collect a ballot paper. The two effects of this, or perhaps the two most immediate effects, are that politicians and political institutions lose legitimacy, and the results of elections reflect the participation of those who do make the effort to vote, who are often to be found towards the extremes of the political spectrum.

Election legend Professor Sir John Curtice of the University of Strathclyde has already warned that we could see low turnout at the impending election. If we look at the levels for 2015, 2017 and 2019—66.2 per cent, 68.8 per cent and 67.3 per cent—you would be optimistic to expect us to climb back beyond 70 per cent this time. Curtice summed it up neatly.

So you have an election where there isn’t much diversity in the parties, it’s obvious who is going to win, and the parties are extremely boring—that’s not a recipe for high turnout.

I think we’ll have dodged a bullet if turnout is above 60 per cent. If you catch me in a gloomy mood, I’d predict it will be somewhere in the 50s, which would be a very bad sign for our democracy, and I know friends who fear it may fall further than that.

Would a very low turnout influence the result of the election? Curtice thinks not, noting “it will probably affect supporters of all the parties”. It is, of course, impossible to say with any certainty. There was a time when we abided by very roughly drawn stereotypes, such as the idea that bad weather on polling day favoured the Conservatives because their natural voters were more likely to own cars and less likely to be reliant on public transport.

However, the Resolution Foundation published research in February which identified a growing gap in likelihood to vote between young and old. Bluntly, “millennial non-graduates and non-homeowners [have become] increasingly unlikely to vote compared to their graduate and homeowning counterparts since the last general election”. Conservatives should not see this as potential salvation, as the mountain to climb remains tall and steep, but I think it is at least possible that it may depress the extent of a Labour victory compared to the figures being shown in opinion polls.

I said all of that less “briefly” than I had intended but it is helpful (for me) to have set it out systematically. It is underpinned, in a strange way, by my original point, that there are distinct and almost irresistible tides in politics that can be sensed but not proven evidentially. Jim Callaghan proposed that such a tide was running against him in 1979, there was certainly one in favour of Tony Blair and New Labour in 1996/97 and there is one against the current government now. But, I suggest, the current tide is very much more anti-Conservative than pro-Labour. Indeed, it is not just anti-Conservative but anti-government, anti-establishment and anti-politics.

Though his arrival in Downing Street is almost certain, Sir Keir Starmer is not the leader to harness an anti-establishment tide. He has some fine qualities, but he is a 61-year-old white barrister who attended a fee-paying school, has an Oxford degree and became a Queen’s Counsel then director of public prosecutions (and by rank and position a permanent secretary). He is not especially charismatic or fluent, and this Adam Boulton-penned comparison with Harold Wilson is bizarre, ignoring the fact that however staid and stolid Wilson may appear to us now, he faced the electorate in 1964 as a modernising and dynamic figure. It is particularly striking that Starmer, a highly successful lawyer, does not even particularly shine at the despatch box, but it is also true that not all successful lawyers are gifted advocates; I am quite prepared to believe that Starmer is methodical, diligent and logical in his thought, and that is a major part of the legal profession.

Whatever happens, I hope we as an electorate somehow manage our expectations. I wrote in City AM last year of my worries that a Labour victory would be followed by acute disappointment when, through no-one’s fault, there is no immediate and dramatic change in our world. Such a response, which would be another grievous blow to our political system, seen too easily as another betrayal of the people by a nebulous “political class”, may be ameliorated by the argument I’ve been making that there is no buzz around Starmer’s Labour, no great sense of anticipation and enthusiasm.

I started writing this essay to talk about the way governments in decline seem to attract bad luck, but it didn’t turn out that way. The argument I’ve sketched out matters, though, and is in some ways a companion piece to this week’s long read in which I imagined what Whitehall might look like under a Labour government. In any event, I will be vindicated or found out in a few months’ time. The general election can come no later than 28 January 2025, but my money is still on October or November. The most important factor, however, is that I doubt a decision has been made. I think Rishi Sunak, the man with the power to trigger the process, is playing this by ear. So we shall see.

I listened to two Starmer interviews on sat whilst cleaning. He comes across as decent, thoughtful, passionate, but dull. He has no overt sparkle or fire that lifts him up and turns peoples heads. He wouldnt be man to lead you over the top. He's a Capt Darling. Pens, paperclips and papers. Nice chap, plays good game, claims he hates losing, so maybe he is ruthless, which may catch his opponents off guard. Its unfortunate his voice is bit of a drawl, and seems to have no accent. He cant be placed. Again possibly an adavatage,just like Rayners staunch Mancunian flat vowels may alienate some and attract others. Whether he will make a good PM, who kniws. Often its shaled by unforeseen events and factors even PM cannot influence. Lets wait and see.