Failing the intelligence test: Israel off guard

The wave of attacks by Hamas last weekend had not been foreseen, despite Israel's respected intelligence capabilities, but many factors can cause unpreparedness

The Day of Atonement

The sun set at around 5.19 pm in Jerusalem on Friday 5 October 1973; two minutes later, night fell in Tel Aviv-Yafo, 40 miles to the north-east. Most foreign embassies were located in Tel Avid because of international disputes over the status of Jerusalem, and East Jerusalem had only come under Israeli control in 1967. Sunset marked the beginning of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the holiest day in Judaism, marked by fasting, a long service in the synagogue and confession of sins. Television and radio ceased broadcasting, the country’s airports closed, public transport ceased and shops and businesses would not open. In effect, Israel, although it had adopted freedom of religion as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights when it joined the United Nations in 1949, turned for a day almost entirely away from the outside world and towards its relationship with G-d.

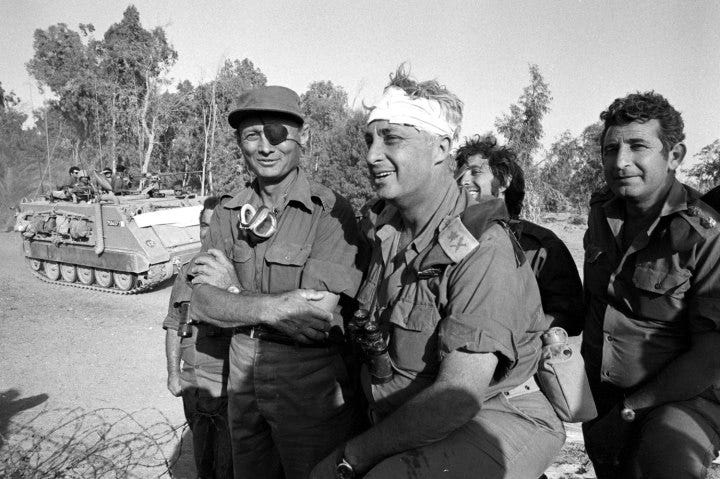

Yom Kippur continued into Saturday 6 October (the Jewish liturgical day runs from sundown to sundown). Overnight anxiety had rippled through the leadership of Israel’s armed forces, as indications, hints, signs began to be noticed that the country’s Arab neighbours were preparing for some kind of military action. Major General Ariel Sharon, who had retired from the army a few weeks before, frustrated at lack of promotion, had been shown intelligence revealing Egyptian units massed on the west bank of the Suez Canal. He contacted General Shmuel Gonen, his successor as head of the IDF’s Southern Command, and told him bluntly that a war was about to start.

Meanwhile Major General Zvi Zamir, director of the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service, had been given similar warnings, but had been unconvinced, doubting that the Arab states were ready for a conflict. Now, finally, he began to accept there was a risk. Early on 5 October, Zamir had received a cable from one of his most reliable agents saying war was certain. Rather than warn his superiors, however, he travelled to the agent’s location in Europe to make certain. At 3.45 am on 6 October, Zamir placed a call on an open line from an Israeli embassy somewhere in Europe to Major General Eli Zeira, chief of Aman, the military intelligence department of the IDF. Zamir told him that an invasion from Egypt and Syria simultaneously would begin at sunset that day, Saturday. However, in a horribly consequential Levantine version of Chinese whispers, this message became slightly distorted as it was disseminated throughout Israel’s leadership, and what had been “in the afternoon hours” became “sunset”. Worse, sunset coming at 5.20 pm, it was then garbled further into a definitive timing of 6.00 pm.

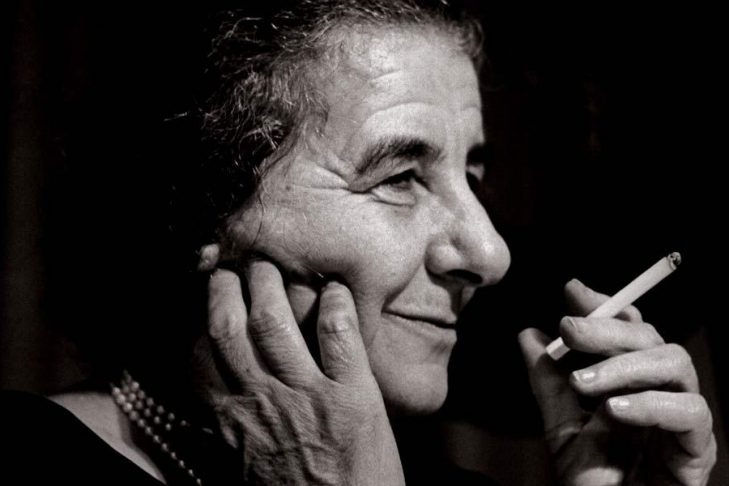

Precision matters. At 8.05 am, the prime minister, Golda Meir, met her minister of defence, the charismatic, eyepatch-wearing Moshe Dayan, and the IDF chief of staff, Lieutenant General Daniel Elazar. The latter proposed that the air force and four armoured divisions, more than 100,000 personnel, be mobilised, while Dayan suggested only two armoured divisions, 70,000 men, as well as the air force. Meir chose Elazar’s plan. After a few moments’ consideration, however, she rejected his further submission, that the IDF undertake pre-emptive strikes that afternoon on Syrian airfields, missile launch sites and ground units. At that late stage, Meir knew that Israel could not be seen to provoke the conflict; the United States had warned against undertaking proactive military action against its neighbours, and without US support, the IDF would be cut off at the knees. President Richard Nixon and his secretary of state, Dr Henry Kissinger, had repeated this warning again and again. So the Israeli high command waited while military units were frantically recalled from their Yom Kippur solemnities. At 10.15 am, the prime minister briefed the recently appointed US ambassador, Kenneth Keating, a congressman and judge from New York who had been emissary to India until the previous year, and assured him that Israel would make no pre-emptive move.

The forces in place for the unexpected attack were enormous. Egypt had 100,000 soldiers and 1,350 tanks in the Suez Canal zone, initially facing only the IDF’s 45-strong Jerusalem Brigade strung out along 16 forts. On the Golan Heights in the north, there were 28,000 Syrian troops and 800 tanks, with two more armoured divisions en route from the rear; the IDF could muster 3,000 soldiers and 180 tanks. Israel’s forces in situ were barely even a tripwire, but until the reserves could be activated, mobilised and deployed, they were the country’s first line of defence. At 2.00 pm, the war began. In the south, Egyptian units crossed the canal with ease and swept aside their opponents and punching through the defensive Bar-Lev Line. In the Golan, an hour of airstrikes and artillery barrage pounded Israeli positions, as well as civilian housing and infrastructure, before Syrian paratroopers raced south to capture the strategically important IDF observation post on Mount Hermon.

The end of the Third Temple?

For three days, the IDF, with its reserves gradually arriving and bolstering the front-line units, reeled, tottered and retreated. But they did not break, and the Arab armies ran out of momentum. Despite serious losses, the Israeli forces rallied and went on the offensive with dramatic effect. Within a week, IDF units were only 60 miles frorm Cairo in the south—much closer than Rommel’s Afrika Korps had ever managed during the Second World War—while in the north they were close enough to shell the outskirts of the Syrian capital Damascus.

For a short period, however, Israel faced a genuinely existential threat. It was perhaps no longer than two days. On 8 October, the IDF mounted its first counter-offensive in the south, as Ariel Sharon, who had been “unretired” and placed in command of an armoured division, prepared to strike westward and was even requesting instructions as to whether he could cross the Suez Canal. This all filtered back to the high command as positive news, but in fact communications had broken down, Sharon’s division had been roughly handled and repelled, and losses had been heavy. The army had lost a large number of tanks, which was bad enough, but it had lost soldiers too, and they were almost irreplaceable.

Although in the north there was better news, with fresh units arriving to take the fight to the Syrians, there was despair at the very top of government that the State of Israel had never seen before. By the evening of 8 October, Major General Benny Peled, the head of the Israeli Air Force, warned that his losses were running at a rate which meant that there would effectively be no air force within a week. Dayan, thrown into depression by Israel’s military setbacks, was heard talking about “the end of the Third Temple” (that is, the destruction of Israel), and Meir had to stop him from holding a press conference in which he planned to use those terms.

During the night of 8/9 October, the first discussions were had about the potential use of Israel’s nuclear arsenal. Almost nothing was or is officially known about the country’s nuclear capacity, but by 1973 it has been estimated that Israel possessed 13 nuclear bombs and 20 missiles. Some of these were relatively low-yield and primitive, comparable in effect to the bomb dropped on Nagasaki in 1945, though as Israel was the only regional power with any nuclear capability at all, that was not such a disadvantage. Some experts have argued that the weapons were unlikely to be stored complete, but would have been kept as components and would have needed a period of time of perhaps half a day to assemble and make ready. We also know nothing about the authorisation process for using nuclear weapons, assuming that the prime minister cannot order their use on his or her sole authority.

At some point, however, there seems to have been a private conversation between Meir and Dayan. The defence minister’s reference to the “Third Temple” was not accidental: “Temple” was the codename for nuclear weapons. In one sense, in a country as small by area, using nuclear weapons against invaders is insanity. Even striking at an enemy capital like Damascus or Cairo would be detonating a devastating device only a few hundred miles away. But one of the scenarios anticipated for the activation of “Temple” was the so-called “Samson Option”, circumstances under which the State of Israel faced the real and immediate prospect of not only conquest and occupation but elimination, destruction. If it was necessary to avoid the fate which Hitler had attempted to impose on the Jewish people, then Israel would have to threaten, credibly, to use its nuclear weapons to do something which would be globally catastrophic; it would have to emulate the biblical judge Samson, who pushed apart the pillars of the Philistine temple and caused to collapse, killing the thousands of Philistines gathered there—and himself.

Caught unawares, and paying the price

The Yom Kippur War of 1973 stands out in history of Israel because it was an existential crisis. Egyptian forces had crossed the Suez Canal and pushed 10 miles into the Sinai Peninsula with five divisions, nearly 100,000 men and nigh on 1,000 tanks. They had also created anti-tank defences armed with new Soviet Sagger guided missiles, which were taking a fearsome toll on the IDF’s armour. In the Golan Heights, Syrian forces had advanced to within 10 minutes of the 1967 border, after which Syria had lost so much territory. Added to these territorial losses the depletion of Israel’s manpower and materiel and the future of the state hung in the balance. How had this happened? Israel had some of the most respected and feared intelligence services in the world, yet the Arab nations had been given the opportunity to throw the first punch, and it had come very close to being a knock-out.

It could not be said there were no indications. In the broadest sense, Egypt was a known threat: by 1972, the country was in economic stagnation. Anwar Sadat had succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser as president in 1970 when the country’s hero had suffered a fatal heart attack, aged only 52. As vice-president, Sadat’s succession was obvious but he was not expected to last. But he proved to be surprisingly resilient and agile, and purged the closest supporters of Nasser in May 1971. He tried to liberalise the economy but foreign investment was sluggish. In October 1972, Sadat told the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces that he intended to begin military action against Israel within a year, whether the USSR supported him or not. He was known to be reequipping the military with new Soviet hardware, and had openly admitted he was willing to sacrifice a million Egyptian soldiers to recapture the Sinai Peninsula.

Sadat seemed to be in earnest: the Egyptian Army conducted repeated military exercises near the border with Israel throughout the summer of 1973, and staged another right by the canal a week before the actual invasion. But Sadat made a show of demobilising 20,000 soldiers, which persuaded the Israelis to think that the Egyptians were de-escalating. Yet the message was driven home. On 25 September, King Hussein of Jordan secretly flew to Tel Aviv to meet Meir, and told her that a Syrian attack in the north was likely. Egypt was likely to co-operate in such circumstances and move across the Suez Canal. Zvi Zamir, at the Mossad, reassured the prime minister that all was well. Although Israel received 11 separate warnings from reliable sources throughout September, the intelligence community could not accept that Egypt and Syria had the willpower or morale to start a conflict. The King of Jordan, Meir was told soothingly, had not said anything which Israel did not already know.

In a sense, they were right. The disastrous failure of intelligence in the Yom Kippur War was not a lack of information: the Israelis had plenty of evidence that a conflict might be imminent. But they could not believe it would happen. The received wisdom in strategic circles was that the Arab nations had been so battered and had lost so much in the Six-Day War in 1967 that they would not risk such an overt clash again, or at least not for some time. The IDF’s pre-eminence was taken as a given, and rationality assigned to decision-makes in Cairo and Damascus. As can happen in intelligence gathering and analysis, and is so dangerous, the leadership of Israel had fixed on a notion that they were safe from war, and every new piece of intelligence was absorbed in that context. It became a self-perpetuating circle.

The government of Israel had assumed that even in the worst possible scenario it would have 48 hours’ notice of any aggressive move against it. And although the Yom Kippur holy day should perhaps have been spotted as a vulnerability, it happened that year that the Day of Atonement coincided with the 9th day of Ramadan, when Muslim soldiers would be fasting during daylight and many had been given leave to perform the Umrah, or “lesser pilgrimage”, to the holy sites of Mecca. The 48-hour assumption could have held valid, had intelligence been interpreted differently, but as it transpired, the Israeli leadership only absorbed the fact that war was coming around 12 hours before Arab forces crossed the borders, and, as we have seen, communications errors caused the Israelis to fixate on a time which, although only a few hours out, was a vital element given the fine margins of error.

Suddenly nowhere is safe

It was 50 years and a day after the beginning of the Yom Kippur War when Hamas terrorists based in Gaza burst through and over the fortified border with Israel last weekend. The so-called “Iron Wall” is an enormously technologically sophisticated and expensive barrier of more than 140,000 tons of iron and steel, using hundreds of cameras, radar arrays and sensors to monitor movement along the border. It has systems designed to prevent tunnelling, after the IDF’s Operation Protective Edge in summer 2014 revealed that Hamas were using tunnels to hide and stockpile weapons, improve communications and move without attracting the attention of Israeli border forces. More than 60 miles of tunnel were destroyed by Israeli airstrikes during Operation Guardian of the Walls in May 2021, but this was the tip of the iceberg.

What Hamas remembered, but the IDF seems to have allowed to become obscured, is that a wall, no matter how high, how thick, how well defended and how lavishly supplied with high technology, is still a wall: the terrorists overcame it—literally, in some cases—by using drones to bomb the observation towers and sensors, using hang-gliders and paragliders to get over the barrier, and destroying some sections of the fence with explosives, allowing armed men through on motorbikes before using bulldozers to widen the gaps and make access easier. Little of this was deploying technology, compared to the sophistication of the Iron Wall itself, but it did require lateral thinking, inspiration and meticulous preparation over what must have been a period of weeks. That degree of forward planning should have revealed itself to Israel’s extensive intelligence networks.

Talking to Foreign Affairs, two-time US ambassador to Israel Martin Indyk highlighted some of the potential failures which allowed last weekend’s attacks to take Israel by surprise. He described it as a “total system failure on Israel’s part”, exacerbated by the Israeli leadership convincing itself, as it had done in 1973, that there was no mood for conflict on the scale which emerged.

They had been confident that Hamas was deterred from launching a major attack: they wouldn’t dare, because they would get crushed, because the Palestinians would turn against Hamas for causing another war. And the Israelis believed that Hamas was in a different mode now: focused on a long-term cease-fire in which each side benefited from a live-and-let-live arrangement.

This “hubris”, as Indyk described it, allowed Israel to believe that its own military strength had contained Hamas, and that the problem of cross-border security was not currently a pressing one. “They thought the problem was under control. But now all their assumptions have been blown up, just like they were in 1973.”

Professor Amy Zegart, a specialist in intelligence, risk and national security at Stanford, emphasised the duality of the Hamas approach: although it represented the defeat of a complex and highly sophisticated security apparatus with run-of-the-mill, low-tech approaches like explosives and bulldozers, the achievement of Hamas should not be underestimated.

This was not an amateur-hour operation. The assault came by air, land, and sea, and attackers fanned out to capture and kill across multiple sites simultaneously. That kind of large-scale sophisticated operation takes careful planning, coordination, time, and practice.

Because of this, there should—must—have been some warning signs which Israeli intelligence ought to have detected. In addition, the very conception of a major cross-border offensive should have been on Israel’s radar (literally as well as metaphorically). As Zegart put it, damningly:

This was a white swan event plotted by notorious terrorists next door. It was precisely the kind of worst-case disaster scenario that Israeli intelligence and defense officials were supposed to worry about, plan for, and prevent.

Yet it was not foreseen. Elena Grossfeld of the Department of War Studies at King’s College London has written a very acute summation for Foreign Policy, which is well worth reading.

Learning lessons after the fact

No doubt there will be some kind of post-mortem on the events of 7/8 October when the immediate crisis has passed. In 1973, a full month had not passed since the end of hostilities before the government asked the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Shimon Agranat, to chair a commission examining the period before the conflict began. The Agranat Commission consisted of the chief justice, Moshe Landau, another member of the Supreme Court, Yitzhak Nebenzahl, the state comptroller who oversees and audits government policies and deals with public complaints, and two former IDF chiefs of staff, Yigael Yadin (1949-52) and Chaim Laskov (1958-61).

The Agranat Commission produced an interim report in April 1974, a fuller version of that report in July and a final version in January 1975. Its headline recommendation in the first volume was the dismissal of four senior IDF officers, starting with the head of Aman, Eli Zeira. It largely exonerated Golda Meir, saying that on the morning of 6 October:

She decided wisely, with common sense and speedily, in favour of the full mobilization of the reserves, as recommended by the chief-of-staff, despite weighty political considerations, thereby performing a most important service for the defence of the state.

But Meir, in her mid-70s and never enjoying the best of health, was struggling. A general election in December 1973 had seen her Alignment bloc lose five seats in the Knesset, while the new right-wing Likud alliance, led by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon, won 39 seats, a spectacular result for a coalition only assembled in September. Meir could not find a combination which consolidated a majority in the Knesset, so, on 11 April 1974, only 10 days after the interim report was published, she resigned as prime minister.

Many have held Golda Meir substantially responsible for the intelligence failures and the close call which Israel experienced in the Yom Kippur War. She was the head of government, and had been since 1969, so she certainly attracts some ex officio blame. It was true that President Sadat had repeatedly offered peace talks over the summer of 1973 on the basis of Israeli withdrawal from Sinai, but they were at cross purposes. Although Meir had previously mentioned the possibility of ceding “most of the Sinai”, she would not countenance returning to the pre-1967 borders, while Sadat would not consider talks on any other basis. As stated above, the Agranat Commission had largely absolved her of responsibility, and there was a more-than-respectable argument that she had been rightly reliant on her advisers, especially the chief of staff and the intelligence chiefs, by the time the immediacy of the threat became apparent.

If she had made some errors of judgement in terms of timing on 5 and 6 October, it had to be remembered that the whole situation had been measured in fragments of hours. It was not as if she had rejected clear advice which turned out to be accurate: no-one had known what was happening, and Meir had certainly not got things more badly wrong than anyone else. Certainly she had not entered the long dark night of the soul which had stolen over Dayan, the defence minister. Dayan was a strange man, immensely charismatic and fearsomely intelligent but remote and hard to read. He vibrated with energy but was mercurial in the extreme. Sharon later said of him:

He would wake up with a hundred ideas. Of them ninety-five were dangerous; three more had to be rejected; the remaining two, however, were brilliant. He had courage amounting to insanity, as well as displays of a lack of responsibility.

Would Meir have survived in office without the election of December 1973? Perhaps. Her moral courage and resolution were beyond question, as was here physical stoicism: she wrote that her earliest memory was of her father boarding up the door of their home in Kyiv because there were rumours of an imminent pogrom. But she was already 71 and a widow when she became prime minister, and a heavy smoker who, unknown to the public, had been suffering from malignant lymphoma since 1966. She was also plagued by heart disease and had suffered a severe leg injury when a grenade had been thrown at the government front bench in the Knesset in 1957. Would good health have made her more determined to remain as prime minister? Again, perhaps. But it may be that her resignation and replacement by former IDF chief of staff and Israeli ambassador to the US, Lieutenant General Yitzhak Rabin, as well as the departure of Dayan as minister of defence when Rabin took over, took some of the heat out of the arguments over responsibility.

Does history repeat itself or merely rhyme?

This question must lurk in the minds of some of the current Israeli cabinet. There are, of course, more immediate concerns, and it may be that the self-confidence of the current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, is so armour-plated that he is not anxious. He is a deeply divisive figure, but what is undeniable is that he is experienced, intelligent and physically brave: for five years he served in the IDF’s special forces, in the most secretive and elite of the units, Sayeret Matkal, and after he left active service in 1972, he re-enlisted during the Yom Kippur War and was involved in commando raids both in the Sinai and the Golan Heights. (His brother Yonatan, of course, led Sayeret Matkal in the outrageous and successful raid to free Israeli hostages at Entebbe in Uganda in 1976, and was the only Israeli soldier killed in the operation.)

Netanyahu’s career is so long that it is hard to recall every aspect of it. He first entered public service as deputy chief of mission at the Israeli embassy in the United States in 1982, then became his country’s permanent representative to the UN in 1984. Young, articulate, fluent in English and comfortable in American English, with an easy sense of humour, he was a perfect spokesman for Israel on the world stage, a generation below the survivors of the Holocaust and the blunt, hard-as-nails veterans like Yitzhak Shamir and Shimon Peres with their grey hair and thick, guttural, eastern European accents. (Netanyahu was born in Tel Aviv and raised in Jerusalem and Philadelphia.) I remember first seeing him in 1990 when he was deputy foreign minister and a Likud member of the Knesset: during the first Gulf War, Netanyahu was the principal spokesman for the foreign ministry, as his chief, Morocco-born David Levy, spoke poor English. If you want a crash course in public diplomacy, you can do a lot worse than study Netanyahu’s media appearances from that time: it was essential for the Arab members of the vast multinational coalition George H.W. Bush had assembled against Saddam Hussein that Israel was not involved in the conflict at all, and Netanyahu played his hand with extraordinary skill.

In 1993, Netanyahu became chairman of Likud; in 1996, confounding many expectations, he beat Shimon Peres to become prime minister. Since then he has rarely been away from the front line of politics, and he is now comfortably the country’s longest-serving premier, having held the office for a total of 16 years (1996-99, 2009-21, 2022 to date). He has always been very tough on security and leveragd his reputation in that regard ruthlessly, but he has also pursued economic liberalism both as prime minister and as finance minister from 2003 to 2005; but he has also been accused of repeated instances of corruption and financial misdeeds. His ability to evade consequences, but he is now, one should not forget, on trial for various chargtes of fraud, bribery and breach of trust, but there is no verdict expected in the near future; prosecution witnesses are expected to be heard until the summer of 2024.

Netanyahu was ousted as prime minister in 2021 when Yair Lapid, leader of the centrist Yesh Atid, and Naftali Bennett of the New Right agreed an alliance in the Knesset which assembled eight groups to achieve a bare majority of 61. Netanyahu became leader of the opposition, Likud still the largest single party with 29 MKs. Al-Jazeera hailed the “end of the road” for the former prime minister and effectively wrote his political obituary. Politico chose the headline “Israel swears in new coalition, ending Netanyahu’s long rule”, but added, in apologetic and small letters “But he vowed to return to power”. Bennett, who became prime minister, had been Netanyahu’s chief of staff in opposition in 2006-08, and was trying to move Israeli politics on, but his former boss was not so easily left behind. He told the Knesset:

I will lead you in the daily struggle against this evil and dangerous leftist government in order to topple it. God willing, it will happen a lot faster than what you think.

Not for the first time, Netanyahu was right. After legislative elections in April 2019, September 2019, March 2020 and March 2021, the electorate was exhausted and disillusioned. The Knesset has a four-year term at most, so there might have been a pause until 2025, but the coalition had a majority of one and could not have been more vulnerable. In April 2022, the government’s coalition chairperson (effectively chief whip), Idit Silman, one of Bennett’s own Yamina MKs, resigned and left the coalition. A religious right-winger, she could not accept the use of leavened bread in public facilities during Passover, and, announcing “I cannot take part in harming the Jewish identity of Israel”, moved to the opposition benches, encouraging fellow religious MKs to follow. A government with 60 votes out of 120 was hopeless, so Israel went back to the polls.

So it was, after another election in November 2022, Netanyahu returned to office. He led Likud to 32 seats, a gain of two from the previous mandate, but the big story was the surge of the ultra-right religious parties like Shas, United Torah Judaism and the Religious Zionist Party. After protracted negotiations during November and December, Netanyahu brought together a coalition of seven parties—as well as Likud and the three parties above, the new government was backed by Otzma Yehudit, Noam and National Unity—and was sworn in as prime minister for the third time on 29 December 2022. He has never been short of enemies, and has managed to accumulate more this year by proposing sweeping reforms to the Israeli judiciary to reduce the influence of judges on legislation, restrict judicial review and give the government control of judicial appointments.

The prime minister’s reputation in the West is doomed by the tag of “ultra-right”, “far-right” or, worst of all, “religious”; the government he leads represents much we simply do not recognise in Europe, or, to an extent, America, particularly the significant influence of religion in the public square. He drives organisations like The New York Times wild, of course. A recent feature by Ruth Margalit, a Tel Aviv-based writer, carried the heavily loaded headline “Benjamin Netanyahu’s Two Decades of Power, Bluster and Ego”, and tried to portray him as a creator of the End of Days: “Netanyahu has pushed Israel to the brink”, “he is besieged on multiple fronts”, “the man looks exhausted”. Margalit grudgingly admitted that the programme of judicial reform, while supposedly unpopular with the electorate, “hasn’t diminished the passion of Netanyahu’s core supporters”, but the implication is that this core is, for want of a betetr phrase, a basket of deplorables. Yet she cites a poll which asked about suitability to lead the country: Benny Gantz, the former IDF chief of staff and defence minister who heads the centre-right National Unity Party, was the choice of 38 per cent, as was Netanyahu. The opposition leader, Yesh Atid’s Yair Lapid, could muster only 29 per cent. That doesn’t seem to demonstrate fringe support in a party system as fissparous as Israel’s.

But we also often nurse a misleading and unrealistic notion that the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians could be solved with a little more compromise, good sense and decency, so Netanyahu’s uncompromising security stance and support among the Jewish settlers in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights make us uneasy. These numbers are not small: there are around 450,000 settlers in the West Bank, another 220,00 in East Jerusalem and 25,000 in the Golan Heights. (The 21 settlements in the Gaza Strip were evacuated in 2005.) The “international community” generally holds these settlements to be breaches of international law, and particularly of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, and it is worth noting that this view, and Israel’s rejection of it, go back to 1967 and the aftermath of the Six-Day War. In general, the Israeli position is that the settlements are in areas which had a “sovereignty vacuum” after 1967, and that the final status of the territories is not yet determined. (It is difficult to see, in political if not legal terms, any Israeli government ceding control of East Jerusalem.)

Bibi in the balance as Israel reels

Netanyahu’s popularity seems to have slumped since the Hamas attacks. A Lazar Research/Panel4All poll this week showed Benny Gantz at 48 per cent as preferred prime minister, while Netanyahu had fallen to 29 per cent. Translated to the Knesset, the National Unity Party would win 41 seats with Likud on 19 and Yesh Atid on 15. Netanyahu has reacted to the security crisis with an unusually consensual move: on Wednesday, he created a three-man war management cabinet, in which he and defence minister Yoav Gallant and Gantz as a minister without portfolio. They will be joined by two observers: Ron Dermer of Likud, minister of strategic affairs and public diplomacy, essentially a communications role; and Lieutenant General Gadi Eizenkot, former IDF chief of staff and now a National Unity MK. A seat in the war management committee has been left open for Lapid. The war management cabinet will meet every 48 hours at least, and the Knesset has granted it powers to issue operational directives to security services, and expand war goals after its first meeting.

This mechanism is catnip to obsessives of systems and bureaucracies like me: but it is also very much standard practice. It was David Lloyd George who pioneered the use of a small group of ministers, largely without specific departmental responsibilities, to act as an overall executive body for conducting the war effort (although reality and efficient operation were achieved by the first secretary of the cabinet, Maurice Hankey); the practice was revived by Neville Chamberlain at the beginning of the Second World War and taken to its apotheosis by Winston Churchill. Robert Menzies, the prime minister of Australia, created a war cabinet in 1939, and President George W. Bush instituted a body with that name after 9/11, though in his case it was almost identical to the National Security Council and included half a dozen members who ran significant departments or other administrative bodies.

For Netanyahu, however, it is a significant extension of a hand across the aisle, and ties National Unity into the government for now; it remains to be seen whether Yesh Atid will eventually join. There are other measures too: five National Unity ministers without portfolio will be added to the political-security cabinet—Gantz, former justice minister Gideon Sa’ar, Eizenkot, Hili Tropper and former education minister Yifat Shasha-Biton—and these changes were agreed by the Knesset on 13 October. As a further bipartisan gesture, Netanyahu has announced that there will be no new legislation introduced nor major decisions made except those relating to the war until the conflict ends, and incumbents in senior public roles will have their terms extended as necessary.

All of these changes are either the actions of a prime minister who believes that the active involvement of other parties will give decision-making more authority and support, or a cynical ploy to tie and potential opponents in to the fate of his own coalition; or perhaps they are both. It is worth noting that at that stage, while Gantz and National Unity have accepted the offer of co-operation readily, Lapid has stood back; he has pledged that he and Yesh Atid will support the government in its prosecution of the war, but Lapid thinks the new structures are complicated and risk duplication (though it is wholly possible this is a cosmetic reason not to join).

The severity of the fall-out from the Hamas attacks on the Israeli government will depend not just on who is found to have been responsible for the lack of preparedness, however that is determined; it will also be affected by the context in which that conclusion is reached, by which I mean how Israel’s retaliation in Gaza progresses. Remember that Israel is now officially at war with Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the security cabinet having confirmed the declaration on 8 October, marking the first state of war since 1973; the Israeli Defence Forces have mobilised 360,000 personnel from their total Reserve Forces Corps strength of 465,000, commanded by Brigadier General Benny Ben Ari (despite fears over the summer that unhappiness with the Netanyahu government might persuade some reservists not to respond if summoned); and the counter-attack, codenamed Operation Swords of Iron, officially began last Saturday, 7 October. (Janes, the global open-source intelligence platform, has a useful timeline.)

Counter-attack: Gaza awaits the IDF’s arrival

Operation Swords of Iron has three principal objectives, as laid out by Netanyahu last weekend. The first, relatively modest and achievable, is “to clear out the hostile forces that infiltrated our territory and restore the security and quiet to the communities that have been attacked”. Essentially this is no more than driving Hamas back into Gaza and making sure that damage to the Iron Wall has been made good, and it was reported on Sunday 8 October that Netanyahu regarded that objective as already largely achieved.. The second objective is a punitive one, “to exact an immense price from the enemy, within the Gaza Strip as well”, and inevitably is unquantified and unquantifiable. But ministers and military commanders will want, to be blunt, big numbers in terms of Hamas losses, and major concrete achievements like the arrest or killing of senior Palestinian leaders and the degradation of Hamas’s military capabilities. This objective may require more careful framing and the construction of a positive narrative around whatever successes the IDF has, suggesting to the electorate that the armed forces are winning.

The third objective, said the prime ministers, is “to reinforce other fronts so that nobody should mistakenly join this war”. This is a message directed to Hezbollah, the Beirut-based Shia militant group, but also Iran, Hamas’s primary sponsor and great rival with Saudi Arabia for regional Muslim dominance. Egypt will of course watch closely but is unlikely to intervene, not least because it has no interest in a flood of refugees from Gaza pouring over the southern border of the Strip into its own jurisdiction.

Indeed, Egypt, if handled correctly, could be a supportive ally. It has a strong interest in the end of Hamas control of the Gaza Strip and its replacement by a group which is less committed to a winner-takes-it-all conflict with Israel. The late Hosni Mubarak, president from 1981 to 2011, was personally active throughout his presidency in trying to encourage the peace process, hosting a number of important summits and giving his director of the General Intelligence Service, General Omar Suleiman, considerable autonomy to work unofficially with Israel and try to undermine Hamas, especially after the withdrawal of Israeli forces and settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005. Relations suffered in the immediate aftermath of the Arab Spring in 2011, Israel’s embassy in Cairo being stormed and ransacked by several thousand anti-Israel protesters in September, but over the course of 2012, they gradually improved, and benefited greatly from the removal of Mohamed Morsi as president in a coup d’état in July 2013.

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Morsi’s successor after a year of an interim president, has proven much more congenial and co-operative. Sisi is undoubtedly autocratic, and becoming more so, allowing virtually no political opposition and turning a blind eye to serious human rights violations by his security forces. In a reductive sense, however, he is pragmatic and values his relations with Israel. In 2016, The Economist described him as “the most pro-Israeli Egyptian leader ever”, perhaps not so lofty a bar, but comforting for Netanyahu as Sisi effectively secures Israel’s south-western frontier.

It is, obviously, the second objective which will determine whether Operation Swords of Iron is successful or not. Netanyahu wants to punish Hamas, but this must also have an eye on extracting such a price that they are effectively removed as a significant threat for the foreseeable future. Given that the Iron Wall has been in place for some years, and there are extremely strict restrictions on what can be taken in and out of Gaza, especially “dual-use” items which might have a military application, additional measures will start from a high bar. Yoram Cohen, who headed Shin Bet from 2011 to 2016, has mooted a 1¼-mile wide, “shoot on sight” buffer zone along the border between Gaza and Israel, which would be a difficult sell internationally and offer almost daily provocation to the Gazan population.

Ambitious and costly though it may be, Israel has to aim for the wholesale dismantling of Hamas’s military infrastructure. The terrorist group has constructed hundreds of miles of tunnels underneath Gaza since it took control in 2007; Israel refers to this as the “Gaza Metro”, while Hamas claims that the network amounts to 500 kilometres—the London Underground system is kilometres, mostly above ground—and this has been used to smuggle arms and supplies into Gaza, to avoid the Iron Wall and move into Israeli territory, to provide facilities for command and control and to avoid the effects of Israeli air strikes. The IDF may seek to destroy this network but it brings challenges: there may be hostages being held in tunnels, some are used for shelter by civilians, some will cause buildings on the surface to collapse if they are destroyed. Meanwhile Hamas are ruthless and adept at using the population of Gaza as human shields to protect their installations.

(Dr Daphne Richemond Barak of Reichman University in Israel has written extensively on Hamas’s use of underground infrastructure and the challenges it poses to opponents. In 2018, she published Underground Warfare, the first comprehensive survey of the subject.)

The Israeli government has for some years accused Hamas of diverting resources from international humanitarian aid to construct military facilities like the extensive tunnel network. Without wishing to be flippant, given that London’s Crossrail has taken nearly 15 years to construct at a cost of nearly £19 billion, one is entitled to wonder how Hamas have been able to create such a formidable project without access to aid money. The near-destruction of the tunnel network must be a major priority of Operation Swords of Iron, or else Hamas will not be defanged, but achieving this will be slow, costly in Israeli military and Palestinian civilian lives and may leave widespread devastation. But realistically it seems like a sine qua non; if it is not a result of the action against Gaza, it is hard to see what will have changed.

It may be easier to degrade Hamas’s military strength significantly, if not completely. On Times Radio this morning, in anticipation of an imminent commencement of action in Gaza, Professor Michael Clarke explained that, notwithstanding recent improvement in. equipment and doctrine, Hamas has a choice to make.

If they choose to fight, most of them will die, because that’s the way the Israelis are now going to take this, they are not in a mood to take many prisoners, so they will die.

This, Clarke goes on, would be a conscious decision by Hamas to sacrifice itself to try to provoke a wider war involving Hezbollah, Iran and Syria, in the hope that such a coalition would be too powerful for Israel to resist. The IDF might, therefore, not have many options but to pursue the deaths of the majority of Hamas militants, no matter what the longer term consequences. In numerical terms, this will not be a small matter. The forces which breached the Israeli border with such horrific effect last weekend numbered around 2,500, but the total strength of Hamas’s armed wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, is thought to be around 40,000 trained terrorist fighters with a range of specialisations. Their training and equipment has improved enormously since Hamas assumed control of Gaza.

But this makes the imminent clash a peculiar one. There is no question is any serious commentator’s mind that the IDF is capable of winning. H.A. Hellyer, a fellow of the Royal United Services Institute who has written extensively on security in the Middle East, put it like this.

The question isn’t whether it’s possible or not. The question is what sort of price will be exacted on the rest of the population, because Hamas does not live on an island in the ocean or in a cave in the desert.

The IDF is being asked, effectively, like Kevin Costner’s Eliot Ness in The Untouchables, “You see what I'm saying is, what are you prepared to do?” The question applies not simply to the deaths of Hamas terrorists, which would have to be in the tens of thousands to be effective, but to the loss of civilian life in Gaza which, tragically, is inevitable and treads grimly in the footsteps of every outrage by Hamas; and it applies also, of course, to losses sustained by the IDF, which could be substantial. Fighting in a built-up, half-ruined urban area is almost the most hazardous setting imaginable; once you add tunnels and potential booby traps, it is a recipe for military units being bled white.

If we can judge from Benjamin Netanyahu’s rhetoric at the first meeting of his war management cabinet this week, he and his ministers have decided to go all in. In a television address, the prime minister was characteristically blunt: “Every Hamas member is a dead man. We will crush and destroy it.” Gantz was no less resolute, pledging readiness to “wipe this thing called Hamas off the face of the Earth”. A spokesman for the IDF said they were prepared:

To execute the mission we have been given by the Israeli government… to make sure that Hamas, at the end of this war, won’t have any military capabilities by which they can threaten or kill Israeli civilians.

The bar has been set high, and Netanyahu would be a fool—and he is not that—not to realise that he may effectively have tied his own political fate to the success of Operation Swords of Iron. RUSI’s Hellyer pointed out that the prime minister had weakened his own position before the attacks took place.

He expended all of this political capital and investment on “judicial reform” and avoiding jail. What's he got to show for it? A security apparatus that seems to have been completely caught unawares and by surprise. And the price of it, the cost of it: humongous.

This seems to be supported by opinion polls. Eighty-six per cent of respondents in a poll by Dialog Center said that the surprise attacks by Hamas represented a failure of Israeli leadership, and 94 per cent blamed the government for a failure of preparedness. A smaller number but still a majority, 56 per cent, believe that Netanyahu should stand down at the end of the conflict. Of course, the State of Israel is at a low and wounded ebb, mourning and on the defensive. With a land, sea and air assault on Gaza expected to begin any time now, as I write, the progress of Operation Swords of Iron could have a huge effect on public opinion either way.

There will be some kind of investigation. At the beginning of this week, Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari, chief of the IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, conceded that point but cautioned that it would not happen until the conflict was concluded. “First, we fight, then we investigate.” There have been suggestions that faulty, or ignored, or misinterpreted intelligence may not have been the only issue: violence has flared up in the West Bank three times this year, centred on the Jenin refugee camp, a stronghold of militant Palestinians, which has drawn resources and attention away from Gaza. Perhaps it will be found that the IDF had become too dependent on technological solutions to border security in Gaza: the human factor in any kind of military operation is always expensive, but its contribution is simultaneously invaluable and unquantifiable. Hamas have become alive to the technological threat too: there are reports that they have stopped using mobile phones and computers for sensitive communications, and hold meetings in rooms which are designed to be protected against surveillance. Netanyahu’s judicial reforms have also been unpopular and some reservists have threatened not to fulfil their responsibilities if called upon, which would have a serious effect on the IDF’s capabilities.

The price of failure

The point has been laboured that the fate of Golda Meir in 1973-74 does not bode well for Netanyahu’s future. But there have been other military setbacks with political consequences. When Israel invaded Lebanon in June 1982 to attempt to subdue PLO formations operating from beyond the border, the IDF found stiffer resistance than it had predicted, and the PLO in possession of more sophisticated weaponry that they had realised. There was also inaccurate intelligence on the potential influence and reliability of Israel’s allies in Lebanon, the Maronite Christians. Operation Peace for Galilee, the codename for the invasion, was compromised not by a lack of intelligence material but by the faulty analysis of what was available.

And there was a price to pay Ariel Sharon, who had reliquished control of Southern Command just before the Yom Kippur War, had become a Israeli Liberal Party member of the Knesset in the December 1973 election which had deprived Meir of her governing coalition, albeit serving only a year, and was then re-elected in 1977, initially for his own centre-right Shlomtzion party but then joining then governing Likud immediately after the poll. Prime minister Menachem Begin appointed him agriculture minister, but after the government was re-elected in 1981, he became minister of defence. Sharon took an extraordinarily hands-on approach to the planning and execution of Operation Peace for Galilee, intending to reshape the geopolitical situation to the north of Israel wholly; the opening phases of the war were marked by intense levels of violence including the almost-unremitting bombing of Beirut and the creation of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees. Coupled with his personal but indirect responsibility for the massacre of 2,000 Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila camps in September 1982, the lack of success in the war overall forced Sharon into resignation in February 1983, though he remained in the government without portfolio.

Intelligence failures happen in other countries, of course, and inquiries or post-mortems are often held. It is, I think, more or less settled opinion now that the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 could have been more clearly anticipated if there had been better information-sharing with the US intelligence community, especially between the CIA and the FBI; both agencies were pursuing al-Qa’eda as an organisation and Osama bin Laden as an individual, but each had different priorities and context. The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States sat from 2002 to 2004 under the chairmanship of Thomas Kean, a former Republican governor of New Jersey, and published The 9/11 Commission Report, which found that senior American leaders had failed to understand “the gravity of the threat” the US faced, as well as recommending structural changes to the country’s intelligence and security apparatus.

But the individual consequences were not high: George W. Bush was emphatically re-elected in the November of 2004 along with his vice-president, Dick Cheney, and the national security adviser, Dr Condoleezza Rice, was promoted to secretary of state for Bush’s second term. The secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld—whose first reaction to American Airlines Flight 77 hitting the Pentagon was, I’ve always thought quite admirably, to go to the site of the crash to help, at the age of 69—would remain in office until the end of 2006. The only significant departures, and they were not explicitly linked to the report, were the director of central intelligence, George Tenet, and his deputy director for operations, James Pavitt, who resigned just under two months before the commission published its findings. Tenet was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom that December.

In the UK, an inquiry into the government’s use of intelligence in the preparations for the 2003 invasion of Iraq was established in February 2004, publishing its findings in July 2004 (it was very much the “quick and dirty” counterpart to Sir John Chilcot’s squeaky-clean, seven-year, 12-volume, 2.6 million-word Report of the Iraq Inquiry). The Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction was chaired by former cabinet secretary Lord Butler of Brockwell, but excluded from its scope the role of politicians, which the opposition parties felt was the crux of the matter in terms of public perception. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats declined to participate officially, although veterna Conservative MP and former Army officer Michael Mates accepted a place on the review in a personal capacity.

Lord Butler concluded that the intelligence used to justify military action against Iraq had been unreliable; that the Secret Intelligence Service was not sufficiently rigorous in testing its sources and had sometimes relied on third-hand information; that caveats by the Joint Intelligence Committee, the body in the Cabinet Office which assesses and co-ordinates intelligence from across the UK’s agencies, had not been made sufficiently strong; that the opinions of Iraqi dissidents had been given undue weight; and—in a very Robin Butler phrase—the conclusions which had been drawn had stretched the available intelligence “to the outer limits”.

Like the 9/11 Commission in the US, though, the Butler Inquiry did not point fingers at individuals. Indeed, the only recommendation it made in that regard was that John Scarlett, who had taken over as chairman of JIC a week before 11 September 2001 and had become chief of SIS a few weeks before the inquiry published its report, should not be required to resign. The only ministerial resignations over Iraq came from those who opposed the invasion, most notably Robin Cook, the leader of the House of Commons, though he was followed by international development secretary Clare Short, health minister Lord Hunt of King‘s Heath and policing minister John Denham. The latter two would return to office after a decent interval. Sir Jeremy Greenstock, UK permanent representative to the UN, later disclosed to the Chilcot Inquiry that he had “considered” being ready to resign if UN Security Council Resolution 1441, arranging for weapons inspectors to return to Iraq, had not been passed in November 2002, but, heureusement, such a state of affairs did not come to pass. Less noticed at the time, Elizabeth Wilmshurst resigned as deputy legal adviser to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in March 2003, allegedly unhappy at the government’s legal authorisation for war. But no-one within government, either minister or official, was dismissed or forced into resignation as a result of the misuse or incorrect analysis of the intelligence material.

A slightly more analogous situation might be the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982. Amphibious forces landed near Port Stanley, the capital, on 2 April; the governor, Rex Hunt, had received a telegram from the Foreign Office at 3.30 pm the previous afternoon warning him that this might happen. It had hardly been worth the warning: the force available for defence of Stanley amounted to 68 Royal Marines under Major Mike Norman and 11 sailors from the survey team of HMS Endurance, an Antarctic patrol ship, with 25 local volunteers of the Falkland Islands Defence Force. The story of the conflict is well known, though anyone interested could do a lot worse than last year’s thorough and absorbing BBC documentary Our Falklands War: A Frontline Story, and Ian Curteis’s magnificent and punchy The Falklands Play, commissioned by the BBC in 1983, shelved, supposedly for being too favourable to Margaret Thatcher, in 1986 and eventually produced with a brilliant cast in 2002.

The point of convergence between the Falklands War and Hamas’s strike on Israel is that the British government was largely taken by surprise. Argentina had been pursuing a claim to the islands, which the British had settled in 1833, for 150 years, and in 1965 the United Nations had urged the two countries to conclude a deal. By the late 1960s, the Foreign Office, while confident of the UK’s legal claim to the islands, was quite prepared to negotiate, regarding the possession as a nuisance: the problems were Argentina, which demanded sovereignty, and the islanders, who rejected anything other than UK rule. There were inconclusive talks at the end of 1978, as the Labour government of James Callaghan dragged itself to its death, but in May 1979, Nicholas Ridley, the acerbic, clever, obnoxious aristocrat who was MP for Cirencester and Tewkesbury, was appointed minister of state at the FCO with the Falklands as part of his brief. Ridley, like many of his colleagues, regarded the maintenance of sovereignty as unreasonably expensive, and negotiated with Argentina a “leaseback” scheme whereby nominal sovereignty would be given to Argentina but British administration would be maintained for a fixed number of years, likely 99.

The deal was rejected outright by the islanders and many Conservative backbenchers, and progress stalled. Ridley told his colleagues in despair “If we don’t do something, they will invade. And there is nothing we could do.” He was half-right. At this point, Argentina, governed by a military junta, was beset by economic problems and widespread civil unrest, and in December 1981 General Leopoldo Galtieri became acting president. The new three-man junta was keen to seize the islands by force, believing that the UK would not be able to respond militarily and that a patriotic move would calm some of the domestic unrest.

The seizure of the islands was a humiliating shock. Three days later, the foreign secretary Lord Carrington resigned, to take responsibility and draw a line under the capture of the territory, and was followed out of office by his deputy and Commons spokesman, Humphrey Atkins, and the minister of state responsible, Richard Luce. The Argentine forces surrendered in 14 June, and three weeks later Thatcher announced the formation of a committee of privy counsellors:

To review the way in which the responsibilities of Government in relation to the Falkland Islands and their Dependencies were discharged in the period leading up to the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands on 2 April 1982, taking account of all such factors in previous years as are relevant; and to report.

The committee was chaired by Lord Franks, then 77 and a man who had held almost every office open to the Great and the Good: professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow before the Second World War; permanent secretary to the Ministry of Supply; Provost of The Queen’s College, Oxford; UK ambassador to the United States; chairman of Lloyds Bank; Provost of Worcester College, Oxford; chancellor of the University of East Anglia. The other members of the Falkland Island Review Committee were Lord Barber, former chancellor of the Exchequer; former paymaster general Lord Lever of Manchester; Sir Patrick Nairne, a former permanent secretary; Merly Rees, former Labour home secretary; and Lord Watkinson, former minister of defence.

Franks and his colleagues worked quickly and Thatcher presented the report of the committee to Parliament on 18 January 1983. Although it made some specific criticism of decision-making, it largely exonerated the government and concluded that the invasion could not have been foreseen. Franks admitted that the government had sometimes behaved as if the UK’s commitment to the islands was wavering or uncertain, but all that mattered for Thatcher was the final paragraph.

Taking account of these considerations, and of all the evidence we have received, we conclude that we would not be justified in attaching any criticism or blame to the present Government for the Argentine Junta’s decision to commit its act of unprovoked aggression in the invasion of the Falkland Islands on 2 April 1982.

There, as with its successor the Butler Review 20 years later, was the characteristic Whitehall approach to reviewing its own actions. In a passive sense, things may have been done wrong, but actively no-one had made any mistakes worth commenting on. There were no calls for resignations, though Peter Carrington had spiked those guns by offering himself as a sacrifice at the beginning of the conflict. The truth was that Franks, scrupulously fair-minded and decent, saw no advantage in hunting for scapegoats, and was aware that Thatcher’s government and James Callaghan’s which preceded it had made errors but should probably bear a sense of collective responsibility.

In any event, learning lessons from Hamas’s assault on Israel is now a process which can be set aside until the conflict is over. Whether this is a matter of weeks or months, it is impossible to say. The government of Benjamin Netanyahu does prima facie seem to have some serious questions to answer, but the history of inquiries in Israeli politics is more robust and critical than that we have here in the UK, or even in the United States. It may also be that nemesis is finally coming for Netanyahu, and he will suffer in part for who is rather than what he did or did not do. But, as he really ought to understand better than anyone, that is how politics, the cruellest of mistresses, works. As one of the great heroes of Red Clydeside, Jimmy Maxton, supposedly said, if you can’t ride two horses, you shouldn’t be in the bloody circus.