Thatcher, Thatcher, leadership snatcher

Margaret Thatcher was a surprise challenger for the Conservative leadership in 1975, but she didn't appear from nowhere

More than any other leader since Churchill, Margaret Thatcher is hedged about with legends and illusions. Her usurpation of the top job from Edward Heath is seen by some as inevitable, a necessary part of the Conservative story as the party went from the electoral and intellectual doldrums to the triumphant dominance of the 1980s. This in some ways means she requires no back story, no origin myth: she was simply there when she was needed, as if someone had sounded Drakes’s Drum.

In any case, the real tale is inconvenient, as she spent the whole of the Heath government from 1970 to 1974 in the cabinet, as secretary of state for education and science, and her colleagues did not afterwards recall her objecting fiercely to any of the policies she would later repudiate. She retained that portfolio partly due to the prime minister’s “determination to keep her corralled in a department removed from the central business of the Government”, according to one of her biographers. In the summer of 1973, the chief whip, Francis Pym (Con, Cambridgeshire), told Heath that Thatcher was well regarded, and deserved promotion, though did not want to be moved to the Department of Health and Social Security. Heath was not persuadable; indeed, in the aftermath of her withdrawal of free milk for schoolchildren over seven in 1971, he had given careful consideration to sacking her.

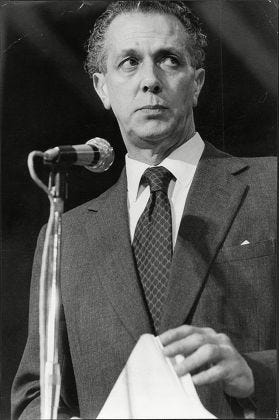

The counterbalancing narrative is that Thatcher was not important for herself when Heath reached his Götterdämmerung in 1975, but was simply the most convenient vehicle for anti-Heath sentiment. There is a sliver of truth in this. Crucial to the tactical management of her victory was Airey Neave (Con, Abingdon), a secretive and sly former intelligence officer and prisoner of war who had been the first British officer to escape from Colditz in the Second World War. Elected to the House of Commons in 1953, Neave had suffered a massive career setback six years later when he had a heart attack at the age of 43, not helped by heavy smoking and drinking (though he gave up alcohol after his illness). It is said that Heath was notably unsympathetic, allegedly telling him “That’s the end of your ministerial prospects” (though Heath would strongly deny this years later). In any event, by the 1970s, Neave, hardly an ideological fellow-traveller of his leader, had come not only to despise Heath but to be determined he must go.

Neave had told Heath the brutal news after the second election defeat of 1974, but the leader was not in listening mode. It was part of Heath’s impenetrable self-confidence that after nearly a decade at the head of the Conservative Party, despite having lost three out of four general elections to Harold Wilson and the Labour Party and leaving Downing Street in ignominy among economic crisis and industrial unrest, he still believed himself the best man for the job. (“Man” is the operative word; Heath had few friends and even fewer female friends, promoted very few women MPs to senior office and would have found it inconceivable that any female Conservative was qualified for the leadership.) Neave therefore began to look for an alternative candidate.

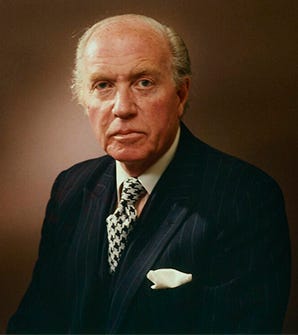

His first choice was Willie Whitelaw (Con, Penrith and the Border), the party chairman, but Whitelaw was unshakeably loyal to the leader and would not move against him (though he would prove willing to contest the top job when Heath was no longer in contention). Next Neave approached the chairman of the 1922 Committee, Edward du Cann (Con, Taunton), who had harboured enmity towards Heath—whose ministerial deputy he had been at the Board of Trade in 1963-64—since being dropped as party chairman in 1967, then denied office in 1970. Du Cann was more enthusiastic about the prospect of succeeding Heath, and for a while in the autumn of 1974 he looked like the most plausible candidate.

But he had a shady reputation in the City of London, where he had earned a great deal of money, not least as chairman of Keyser Ullman, a venerable merchant bank which was very active in corporate finance. It had made some very unwise loans and was badly exposed, and there was no shortage of people to place the blame at du Cann’s door. He was smooth but regarded as untrustworthy: even Tiny Rowland, whom Heath had described to the House of Commons as “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism”, remarked “Edward du Cann is so oily, you could bottle it.” These kinds of uneasy feelings were still enough to cause shockwaves in the Conservative Party in 1974-75, and du Cann began to dither about the leadership. By the beginning of 1975, he was making it known that his wife did not wish to be the spouse of a leading politician. Not least of her considerations was financial: du Cann’s City role was well paid, whereas the leader of the opposition received a salary of £4,500 (about £48,000 at 2023 rates).

Sir Keith Joseph was another potential replacement for Heath, at least in ideological terms. A brilliant but indecisive thinker who had won a first in jurisprudence at Magdalen College, Oxford, then been elected to a prize fellowship at All Souls’, where he began a thesis on political, racial and religious tolerance, Joseph, like Thatcher, had held the same cabinet position throughout the Heath government, as secretary of state for social services. He had presided over one of the highest-spending departments in Whitehall, and, again like Thatcher, had not kicked appreciably against the Heathite pricks. Unlike Thatcher, however, he admitted to a kind of Damascene conversion in the months after the defeat of the Conservative government in 1974; indeed, he was if anything too abject in his recantation of his former views as he embraced the free market, monetarism, Hayek and Friedman. He declared that year that:

it was only in April 1974 that I was converted to Conservatism. (I had thought that I was a Conservative but now I see that I was not really one at all).

This frank and self-flagellating confession made others who lacked Joseph’s honesty uncomfortable. And it infuriated Heath. In what he perhaps imagined was a charitable judgement, the leader declared that Joseph was:

A good man fallen amongst monetarists. They’ve robbed him of all his judgment. Not that he ever had much in the first place.

It was stereotypically Heath that he could not resist that last barb: he would forever say the quiet part out loud.

Joseph was, in the absence of Enoch Powell, who by the second election of 1974 was the Ulster Unionist Member for South Down, the intellectual dynamo behind the reinvention of Conservatism. Without him, the Thatcher revolution would simply not have happened. And his clarity of thought, and ruthless honesty, for a while made him seem the obvious choice to lead the party to its new philosophical home. In fact it was never a realistic prospect. Joseph had no political antennae nor that intuition for what would and would not fly to take the top job. And his effective departure from the contest demonstrated it amply; later he would say candidly and without rancour or regret “it would have been a disaster for the Party, country and for me”.

On 19 October 1974, Joseph, then shadow home secretary, gave a speech to Edgbaston Conservative association at the Grand Hotel in Birmingham. (Students of the curious might note that it is a few hundred yards from the Midland Hotel, where in 1968 Enoch Powell had given his so-called “Rivers of Blood” speech.) He began by lamenting that the recent general election campaign had been dominated by economic arguments, and suggested that politics could and should be concerned with wider issues than that. He talked about “liberties, decentralised power, individual responsibility and interdependence”, and then identified his main theme, “the family and civilised values”.

A wiser politician might have heard alarm bells ringing as he launched into a discussion of the central importance of social institutions to the fabric of the political nation. He was soon making reference to Rousseau—in Edgbaston they speak of little else—good and evil, self-discipline and the permissive society. His essential argument would still resonate with conservatives today: “The Socialist method would take away from the family and its members the responsibilities which give it cohesion.” He refuted the supposed connection between deprivation and crime, reminding his audience that Britain was more prosperous than it had ever been, even in the slough of the mid-1970s, yet there had been a huge rise in “delinquency, truancy, vandalism, hooliganism, illiteracy, decline in educational standards”. There was more. “Teenage pregnancies are rising; so are drunkenness, sexual offences, and crimes of sadism.”

This was reliable o tempora o mores! stuff for a Conservative constituency association, and all might have been well, but it was a lurch towards the end that would see Joseph come unstuck. “I am not saying that we should not help the poor, far from it,” he declared, proof positive that there was a good chance people would think exactly that. But help had to be cooperative and fostering self-reliance, not creating more dependancy. Then it all went horribly wrong:

The balance of our population, our human stock is threatened… a high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers least fitted to bring children into the world and bring them up. They are born to mother who were first pregnant in adolescence in social classes 4 and 5. Many of these girls are unmarried, many are deserted or divorced or soon will be. Some are of low intelligence, most of low educational attainment. They are unlikely to be able to give children the stable emotional background, the consistent combination of love and firmness which are more important than riches. They are producing problem children, the future unmarried mothers, delinquents, denizens of our borstals, sub-normal educational establishments, prisons, hostels for drifters. Yet these mothers, the under-twenties in many cases, single parents, from classes 4 and 5, are now producing a third of all births. A high proportion of these births are a tragedy for the mother, the child and for us.

You did not have to be especially suspiciously minded to hear the horrible echo of eugenics in this paragraph. This was, remember, less than 30 years after the Second World War, since the discovery of the horror of the concentration camps and death camps of the Nazi régime. Of course Joseph himself was Jewish, quietly but firmly so, and no-one would have suggested that he was a latter-day Mengele lovingly cradling his craniometer and hypodermic needle. And there were many renowned figures who had genuinely and wholly steeped themselves in the ghastly implications of eugenics, from Beveridge and Keynes to Shaw and Wells.

The speech created a firestorm. The Evening Standard’s headline screamed “SIR KEITH IN ‘STOP BABIES’ SENSATION”. It was almost immediately obvious that if Joseph had ever had a serious intention to run for the leadership—and that is far from clear—then it was a forlorn hope now. He began to make it clear that he was not a contender, and it was at this point that Thatcher came to the fore. Hearing that Joseph, whom she respected enormously and for whom she had a strangely tender fondness, was abandoning any hopes of the crown, she told him “If you’re not going to stand, I will, because someone who represents our viewpoint has to stand”. Joseph’s response, perhaps partly in relief, was “I will give you all my support”.

Finally Neave had his candidate. From hereon in, the story is well known. Neave used all his guile and wits developed during wartime to persuade wavering Conservative MPs to back Thatcher just to give Heath a fright, or to force a second ballot in which the “real” candidates (which by this stage largely meant Whitelaw) would emerge. Was Thatcher just lucky, in that everyone else self-destructed while she held firm, avoided catastrophe and was left to pick up the pieces? Is it fair, to take the argument to its extreme, to think that Neave could have made almost any leading Conservative a challenger to Heath? I think not. Of course she was lucky, but all successful politicians are lucky, and there is truth in Gary Player’s observation that “The harder I practice, the luckier I get”. And there is one neglected strand to the narrative which helps to explain how Thatcher was able to be in a position to have a crack at the ball when, using Boris Johnson’s phrase, it came loose from the back of the scrum.

After the October 1974 general election, the Labour Party was confirmed in government by the narrowest of margins, going from a minority administration to having majority of three. Labour was hardly in vigorous health: not only was it operating with a wafer-thin plurality, it was deeply divided on the matter of Europe and on other issues as well, and Harold Wilson, now in his seventh year overall as prime minister, was tired, increasingly paranoid and fearful that his formidable mental faculties were beginning to erode.

But the opposition was hardly in a fit state to capitalise on Labour’s woes. On the day of the election result, pleas of Heath that he should resign had come from Lord Carrington, the sceptical, witty aristocrat who had until recently been chairman of the party and was leader of the Conservative peers; Jim Prior, the avuncular farmer who was shadow leader of the House of Commons and one of Heath’s closest advisers; and Sara Morrison, vice-chairman of the party, wife of Charles Morrison (Con, Devizes) and great-granddaughter of Irish Unionist leader Walter Long, as well as one of Heath’s only female friends. Incredibly, Morrison’s first choice to replace Heath was Ian Gilmour (Con, Chesham and Amersham), a lanky, languid, very liberal soon-to-be baronet who had been defence secretary in the dying days of the Heath administration. To imagine him as party leader was more than bizarre; it was positively surreal. He was an indifferent speaker, enormously grand (his wedding had been attended by Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth) and enormously rich, and he bore the wearily accepting patience of a man whose brilliance the world was failing to recognise. In 1973, Pym had recommended Heath drop him from the government. But I digress.

I have written previously about the last year of Heath’s leadership in terms of how he wanted to shape the Conservative Party. He made some shadow cabinet changes after the October defeat, and Margaret Thatcher was one of those affected. She had spent the brief 1974 Parliament as shadow environment secretary, not a glamorous brief but one which gave her responsibility for housing and local taxation, two important bread-and-butter issues. She was generally felt to have performed well both in the Commons and in the election campaign, although at this stage—late 1974—she did not believe there would be a female prime minister any time in the near future, as she had famously declared on BBC1’s Val Meets The VIPs in March 1973. Her ambition, therefore, was to be chancellor of the exchequer, a position which, writing in 2023, has still never been held by a woman (the only remaining cabinet post to have that distinction).

Heath was never likely to appoint Thatcher as his shadow chancellor. He had not yet developed the titanic antipathy towards her which would mark their later relationship, but he regarded her as a middling colleague at best, and found her personal manner abrasive—in his defence, he was hardly alone in that regard—and in any case he never willingly appointed those whom he found uncongenial to senior positions. In fact he retained Robert Carr (Con, Carshalton), who was not especially suited to the role; he had been a smooth and emollient employment secretary (though he had passed the Industrial Relations Act 1971 to which the Labour Party had been bitterly opposed, and which had been repealed the previous July); and he had steadied the ship at the Home Office after Reginald Maudling’s (Con, Barnet) resignation in 1972. But he was no fierce attack dog, and was significantly outgunned at the despatch box by the chancellor, the fearsome and hard-punching Denis Healey (Lab, Leeds East), who was emerging as the hard man, both oratorically and intellectually, of the tepid Labour government.

What Heath did do was make Thatcher number two in the Treasury team, shadow chief secretary opposite the warm, cerebral Manchester Jew Joel Barnett who was renowned for a firm grasp of detail and had won his spurs first on the Public Accounts Committee and then as a frontbencher in opposition. On the face of it, this was a slap in the face for Thatcher: although she remained in the shadow cabinet, she was a former departmental chief in office and was now relegated to a supporting role.

Nigel Lawson, the newly elected Member for Blaby in Leicestershire, reflected on this unlikely pairing in his memoirs, The View from No. 11: Memoirs of a Tory Radical. He described Heath’s appointments as “giving the job of the front legs of the pantomime horse to Robert Carr and that of the back legs to Margaret Thatcher”. But Lawson, who would serve alongside Thatcher on the standing committee scrutinising the forthcoming Finance Bill, noted that her principal task was to take Labour on over their impending Budget. With commendable practicality, therefore, and a lack of pique which was creditable and wise in an ambitious politician, she buckled down to the task presented to her. Her performance over the following few months would go a considerable way to moving her towards the party leadership.

Thatcher was given her opportunity to shine very quickly. On Tuesday 12 November 1974, Healey introduced his third Budget of the calendar year. The previous day, sterling had hit a 10-month low against other major currencies, closing at $2.33 while gold dropped to $182 an ounce. The measures increased VAT on petrol to 24 per cent in an attempt to cut consumption, given that the oil crisis caused by the Yom Kippur War had hit only 13 months before, and cut subsidies to nationalised industries. They also eased the Price Code to allow businesses to pass on raised costs to the consumer. In addition, the chancellor replaced Estate Duty with Capital Transfer Tax (renamed Inheritance Tax in 1986). The overall aim was to ease pressure on the company sector, and the total financial benefits were expected to be around £1½ billion.

Healey was in full crisis mode, defying the opposition to take on the measures he had announced as vital to restoring a degree of economic health. He hoped that there would be no “pressure on resources, a further deterioration in our balance of payments [or] a disproportionate increase in the money supply” (an interesting whisper of monetarist policy to come). He concluded by arguing that he had taken the steps necessary, and that there was no other responsible course of action.

I have struck a balance which I dare say will satisfy nobody completely. But I believe that in our present situation it provides a sound foundation for that fundamental reconstruction of our economy which we need. In that sense, I ask the House to approve it as a basis on which all sections of our people can combine in a united national effort to restore Britain to the place she should have in the world.

On 14 November, the debate on the Budget measures began in earnest, opened by the chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster, Harold Lever. Like Barnett from the Jewish community in Manchester, he was the prime minister’s economic adviser and what his obituarist called “a financial wizard”, sitting on all the relevant cabinet committees and deploying his substantial business and investment experience to tackle the knottiest problems facing the government. It would be Thatcher who replied on behalf of the Conservative Party, giving her an advantageous dose of the limelight at a difficult time.

By her own slightly dour standards, she was in high spirits, remarking that:

I always felt that I could never rival him at the Treasury because there are four ways of acquiring money, to make it, to earn it, to marry it and to borrow it. He seems to have experience of all four.

She went on to damn him with faint praise, commending his enthusiasm for private enterprise but emphasising how isolated in the Labour Party that made him. Again she twitted him: “just as I have been a statutory woman in the Cabinet, he is perhaps a statutory moderate in the Cabinet now”. And she had ammunition to spare for the chancellor too, saying derisively of Healey “I have never known a Chancellor take so long to communicate so little to the general public”. Thatcher proceeded to work through the Budget measures one by one, paying close attention to the financial and economic details.

In a way which would become characteristic of her parliamentary style, Thatcher was withering about Healey’s references to profitability and a healthy private sector. These were firmly in her bailiwick, after all, increasingly so as she began to absorb and articulate free market and monetarist ideas. She wound up by accusing Healey of masking bad news amid technical jargon and statistics, or “sacrifice by instalments”. Her conclusion was scathing and minatory.

We got what sometimes happens in Budget speeches. There was a reaction the first day which was quite different from the reactions on the following days as people began to understand the Budget. It would have been better if he had prepared the people for what lay ahead. The people were ready. The Chancellor was not. He and they will regret it.

She had performed well, with vigour and a firm grasp of details. Of course, this kind of close combat played to her strengths, and she was careful to remind her colleagues of it. Her education had been in science, and her early professional career as a research chemist instilled in her a concentration on facts and a logical and deductive method of argumentation. She then undertook legal training, was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1953 and specialised in taxation: she could hardly have had a better grounding for the task of taking on the Treasury team on Budget measures.

Thatcher’s next significant outing was to lead for the opposition on the Finance Bill in December. After a Budget is announced, the House agrees the resolutions which the chancellor has unveiled. Those resolutions are then translated into a finance bill, which has a quirk compared to normal bills. While most legislation is considered in committee either by the whole House or by a standing committee (now public bill committee), the finance bill is generally split, with some clauses being considered on the floor of the House and others being “taken upstairs” in a legislative committee.

The House considered the bill at second reading on Tuesday 17 December. The debate was opened by Joel Barnett, the chief secretary, while Thatcher, opening for the opposition, presented a reasoned amendment (this is a device which objects to a second reading and gives the grounds on which the House should vote against it). It was a comprehensive rejection of the bill, whose provisions “in the present critical state of the economy, are inadequate and in some respects damaging and which also provides, without good reason, for the retrospective repayment of tax to one section of taxpayers”.

Thatcher tore into Barnett’s speech, and at this relatively early point you can hear phrases which would become resonant and characteristic of the Thatcherite creed: “tax on wealth”, “favours the spender but penalises the saver”, “prosperous companies and good dividends are vital”, “the nation would be living on its seed-corn, which is a sure recipe for calamity”. In an interesting presentational twist, to underline the harm it was doing to the economy, she warned the House that “inflation was one of the biggest single taxes”. It was a good punch. Finally, she concluded by attacking the government on a broad ideological front, trying to put what we now call “clear blue water” between the parties.

There is a doubt whether the Government want a flourishing, independent, private enterprise sector in industry. It is not enough to say that he does want such a sector—his actions must prove that he does.

Barnett had warned Thatcher that there would be a large number of amendments to the bill and the committee stage would be intense. He had picked the wrong target, as Thatcher had always relished hard work. She batted the warning back, expressing surprise that the government had only scheduled 10 sittings in standing committee if there were so many amendments expected. “Let me warn the Chief Secretary that I am a very good night worker.” Clearly the opposition would not want for stamina.

Thatcher’s speech was not stylish or ringing. It produced no phrases which were captured for posterity or tucked away for miscellanies. But that was not Thatcher’s way: the quotations which are preserved were mostly written for her, and she often had to be coached heavily to get the intonation right. Instead, it was an address that was detailed, closely argued, logical and aggressive. This was a grim time for the Conservative Party, and both sides felt quietly that they might be running out of solutions to what seemed like persistent economic crisis. If Labour’s mightiest brawler, Denis Healey, had come out swinging with his Budget speech in November, here was Thatcher producing a response at least as ebullient and self-confident.

The strength of her contribution was immediately notice, and attracted remarks from some unlikely quarters. One new Member, Margaret Jackson (Lab, Lincoln), who would become more famous under her husband’s name, Beckett, observed “I have never heard the right hon. Lady speak before and was much impressed by her fluency and by the logic of many of the arguments she put forward”. Equally, the Liberal Treasury spokesman, John Pardoe (Lib, Cornwall North), who had a reputation as a harsh partisan, described Thatcher’s speech as “a splendid demolition job”.

Perhaps a more unexpected if characteristically ambivalent commendation came from the new Ulster Unionist spokesman, Enoch Powell (UUP, South Down). Although Powell had been one of the very first Conservatives to embrace free market economics, resigning along with the rest of Macmillan’s Treasury team in January 1958 over increases in government expenditure, he had since drifted a long way from the party—or, as he put it, the party had drifted far from him, and in the first election of 1974 he had not only declined to stand as a Conservative candidate but had advised the electorate to vote Labour. This had caused a great deal of ill-feeling among loyal Conservatives, even those who were generally sympathetic to his views, but Powell was a prisoner of his rigorously logical brain. “Poor Enoch,” his friend Iain Macleod had said, “driven mad by the remorselessness of his own logic.”

Powell’s exile from the House of Commons which he loved proved brief. With a second election in October 1974, the field opened again, and Powell had become friendly with James Molyneaux (UUP, South Antrim), a rather dour right-winger and senior Orangeman. He agreed with Molyneaux, who would become the Ulster Unionist leader at Westminster after October when the party chief, Harry West, was defeated in Fermanagh and South Tyrone, that he wanted to be a unionist candidate, and was selected, and elected, for South Down. This gave him a ringside seat for the Conservative leadership struggle on which his views were often sought, and for which he was occasionally, if impractically and implausibly, bruited as a candidate.

Powell’s own speech in the second reading debate is worth reading. It has his characteristic timbre and rhythm, a manner of speech which came naturally to him without notes or rehearsal and could be so starkly compelling in the atmosphere of the House of Commons as well as on the public stage. But it is interesting in this case because one could easily imagine it, under other circumstances, coming from Powell the shadow chancellor on the Conservative front bench.

When he came to Thatcher’s contribution, he praised but wrapped the compliment in barbed wire, as he always seemed to feel obliged to do in relation to her. (Asked in old age whether he was pleased that she had carried many of his ideas into government, he paused and said “Yes, but I was never sure she understood them”.) He noted that her speech had been an effective attack on the government’s Budget proposals, but did very little to propose alternative policies.

I do not think I have ever heard inflation denounced more convincingly. Satan never rebuked sin with such eloquence as she denounced inflation. There was nothing missing. Inflation finished a prostrate opponent. Then one waited; for surely something ought to have followed.

It was a fair observation for a man who lived and breathed political ideas, but it equally ignored parliamentary and partisan reality: this was the beginning of a parliament, and while the government’s majority might be wafer-thin, it had the possibility of lasting for five years. What the opposition needed to at this stage was land some blows on the government. Offering up detailed alternatives, especially as the leadership was in some doubt, was simply not on the agenda. Perhaps Powell knew that.

Crucially, perhaps, given what would happen over the following months, Airey Neave was impressed. His diaries, given to Charles Moore for his authorised biography of Thatcher, recorded “I heard part of a brilliant speech by Margaret Thatcher on the Budget. She dealt very well with… the Social Contract, was amusing and increased her reputation.” An impartial observer might dispute the adjective “amusing”, but Neave’s brief comments and instructive in that the cover style and substance, as well as confirming that this was a shift in mood towards Thatcher. It is also interesting that his diary, presumably intended as a private record, refers to “Margaret Thatcher” rather than, say, “Margaret”. There was not, it would appear, a very close relationship between the two as late as November 1974, while they would develop a hugely close friendship during her time as leader of the opposition.

Revealingly, it was not just the strength of Thatcher’s performance which was noted. Members knew that there was a wider context and they knew what was at stake. Winding up for the government, the financial secretary to the Treasury, Dr John Gilbert (Lab, Dudley East), a rather grand, pinstriped intellectual with a sharp wit, wondered aloud why Thatcher had performed so strongly at this point in time.

I suspect that one could be forgiven for thinking that it was a two-day debate in connection with the leadership stakes of the Conservative Party.

The House responded knowingly, and he went on the suggest they might see other similar performances.

At the rate we are going, we can no doubt expect shortly to have the pleasure of maiden contributions on the Finance Bill from the right hon. Member for Bridlington [Richard Wood] and the right hon. Member for Penrith and The Border [Willie Whitelaw].

To digress for a moment, it is striking that he mentions Richard Wood, presumably as a potential leadership contender. He was the youngest son of the former foreign secretary and ambassador to Washington the Earl of Halifax, and had entered the House in 1950. Wood had been given ministerial office in 1955 and had risen to the rungs just below the cabinet, and for the whole of the Heath government he had been minister for overseas development. The Ministry of Overseas Development (ODM) had been created in 1964 and was a classic early Wilson project, combining the functions of the Department of Technical Cooperation and the overseas aid policy functions of the Foreign, Commonwealth Relations, and Colonial Offices and of other government departments and being headed by a cabinet minister, initially Barbara Castle. Heath had merged it into the Foreign Office but it retained a degree of autonomy.

Wood was not an obvious candidate to lead the Conservative Party in the mid-1970s. Modest and likeable on a personal basis, he was, like his father, a dedicated churchman and High Anglican, conservative on moral and religious issues. He opposed the liberalisation of the divorce laws; in March 1951, he had proposed a reasoned amendment to stop the second reading of Eirene White’s Matrimonial Causes Bill, which would have allowed a marriage to be terminated without fault after the husband and wife had lived apart for seven years (which hardly seems precipitate or reckless to modern sensibilities). After an offer by the attorney-general, Sir Hartley Shawcross, to refer the matter to a royal commission, Wood obtained the leave of the House to withdraw the reasoned amendment and White wanted to withdraw her bill; but there was a terrible procedural muddle which Speaker Clifton Brown managed rather clumsily and the bill was given a second reading. A royal commission on marriage and divorce, chaired by the experienced Scots law lord, Lord Morton of Henryton, was indeed set up in September 1951, but it took four-and-a-half years to report. It was split nine-nine on whether the grounds for divorce should be relaxed, and eventually concluded that they should not.

His most recent tenure, at overseas development, had hardly captured the public imagination. He and his sparky Anglo-Irish wife Diana had undertaken a great deal of foreign travel, but much of it had been rather hollow diplomatic formalities. During the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, he had presented the government’s policy of suspending aid to East Pakistan (Bangladesh) pending a political solution to the conflict, while maintaining that aid should in principle not be used as a tool of diplomacy. In July 1972, he had caused some feathers to be ruffled by refusing to publish the report of a committee chaired by former permanent secretary Sir Matthew Stevenson on the status and function of the Crown Agents, which his shadow, Judith Hart (Lab, Lanark), called “quite disgraceful”. So it was difficult to see why Wood should be considered a plausible successor to Heath, unless there were sections of the party which longed for the reassurance of a toff, educated at Eton and New College, Oxford, and an officer in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps during the war. Wood himself joked to a reporter “Some of my friends have ideas above my station”.

(There was one other consideration: Wood had lost both his legs in Libya in 1943, and walked on prosthetics. When he first saw his father, Lord Halifax, after sustaining his life-changing injuries, the older man said “I’ve had one hand all my life and I’ve managed. I’m sure you’ll manage without legs.” They never spoke of it again.)

I digress again. Clauses 5, 14, 16, 17, 33 and 49 of the Finance Bill had been committed to consideration on the floor of the House, while the rest of the bill went upstairs to a standing committee. The initial work was done by David Howell (Con, Guildford), briefly a civil servant in the Treasury’s Economic Section then for four years a Daily Telegraph journalist; in the Heath administration he had been a minister at the Civil Service Department then two lashed-up crisis departments, the Northern Ireland Office and the Department of Energy. He had a first in economics from Cambridge and was an enthusiastic and intellectual technocrat but sometimes a rather pedestrian speaker. But his methodical and exacting style was well suited to line-by-line consideration of a complex and technical bill.

While Thatcher would lead the opposition team in the standing committee, the other Conservative members are worth noting. As Lawson identified in his memoirs, no fewer than eight of them would go on to serve in cabinets under Thatcher: David Howell, Norman Lamont, John MacGregor, Tony Newton, Cecil Parkinson, Peter Rees, Nicholas Ridley and Lawson himself. Only really Lamont, Lawson and Ridley were signed-up free marketeers, though Parkinson would attach himself strongly to Thatcher’s leadership, gain her trust and esteem and for a time be regarded as her eventual heir, before he brought himself low with personal scandal. Ridley too self-destructed after comparing the Common Market to the Third Reich. But all would become at least middle-order batsmen in the Thatcherite XI, and Lawson would be much more than that.

The standing committee considering most of the Finance Bill sat from 15 January to 11 February. Thatcher was the lead spokesman, and so had to divide her time between the committee room upstairs and the chamber where the provisions committed to the whole House were debated. Taking a bill through the House, and especially through committee, is a gruelling task, and so too is opposing it. The latter task comes with no support from civil servants, and is perforce a largely reactive affair. The government has the numbers to keep going, and the opposition can only distract and delay. There are small but important practical considerations: committee rooms in the main building of the Palace of Westminster are mostly grand but frequently uncomfortable, with stiff-backed chairs and fixed desks. They bake in summer and freeze in winter. Sittings can be long, only water may be consumed in the committee room, and Members do well to ration toilet breaks because the proceedings will not stop for them (unless their departure means the attendance drops below the quorum: I once had to tell a Member who needed to use the bathroom that he was necessary for our quorum and that the committee would have to suspend, very visibly, if he left; alas his need was to great for him to be swayed, and suspend we did).

The first day of Committee of the whole House was Wednesday 15 January. Howell made the early running, with conscientious and meticulous attention. The shadow chief secretary kept her powder dry until the end of the debate. When Thatcher rose to reply to Joel Barnett’s wind-up, she started on an aggressive note: “Seldom have I listened to a more unsatisfactory reply to a debate, and seldom have I heard one which angered me more.” She was a rare politician who could use anger to her advantage in the House; as she anyway lacked humour, it projected a sense of disappointment that the government had failed to uphold the standards she expected. One new tax was dismissed as “constitutionally amoral”, and again she hammered away not just at the Budget measures but the government’s whole ideological platform: “This Government hate the wide distribution of private property and dislike people enjoying the fruits of savings income”. Nevertheless, the government’s numbers held and the Conservative amendment was negatived.

Although she then handed the baton back to Howell, she remained alert and ready to pounce. As Barnett outlined a measure dealing with those severely disabled by accident or illness, she intervened to accuse the government of proposing “wilfully to make the situation worse for this group of disabled people”. For Thatcher it was not enough that the Labour ministers were wrong; they knew they were wrong. It was striking, and surely Members present would not have missed the comparison, that when the shadow chancellor, Robert Carr, spoke later on, he was mild-mannered and almost consensual.

The House resumed its consideration on 21 January. Thatcher was quick out of the traps, demonstrating a sharp awareness of the House’s procedures. Raising a point of order, she sought the opinion of the chairman of ways and means, George Thomas (Lab, Cardiff West), on the admissibility of amendments. Essentially, one of the Budget resolutions had been so tightly drafted that it was impossible for the opposition to propose the changes they wanted. Quite properly, she did not challenge the selection of amendments, which is at the absolute discretion of the chair, but asked if the government could table an enabling resolution to widen the scope of debate. Thomas, who would later become famous as speaker of the House from 1976 to 1983 and the first speaker to be heard on radio when the Commons was broadcast from 1978, was charmed by Thatcher’s deference.

I am obliged to the right hon. Member for Finchley. She has interpreted the ruling much better than I was about to try to do… I am afraid that I can only rule that the amendments are out of order because they are beyond the scope of the resolution. I have looked at this difficulty in many ways to try to help the right hon. Lady. I am afraid that she must wait until the next Budget.

She then fell silent for a while as her colleagues took up the cudgels, though her continued presence can be traced through occasional interventions recorded in the Official Report. At one point she interrupted to warn the chancellor, Denis Healey, with what sounds like relish that “we have a great deal of work to do tonight”. It was almost 11.00 pm when she returned to the despatch box.

Healey had just finished speaking, and had to clarify that he had concluded his remarks rather than just given way. Immediately Thatcher was belittling him, no mean task in the case of the burly brawler of a chancellor. But she accused him of not understand what the debate was about.

The Chancellor has us worried not only that he does not understand estate duty, or the new tax which replaces it but that he does not appreciate the full effects of the capital transfer tax he is proposing on the life of individuals, on the economy of the country, or on the whole of free society.

There we have it again, the Thatcherite “free society” and “the life of individuals”. She launched into a defence of the right and ability, indeed responsibility, of individuals to save and invest. For her, that kind of personal thrift was the foundation of a prosperous society. She pretended to be unable to grasp why Healey could not share her point of view.

If two people come out of college or school together and start in an identical job, with identical wages or salaries, they will finish their lives with wholly different wealth: one could save and the other spend. The distribution of wealth between people would be different one from another. That would be totally fair because they would be aware that they had chosen to do it. One had chosen to pass on his wealth to his children. Why not? Why does the Chancellor take such objection to such efforts for one’s children? Some think of it as a duty and privilege.

That is the perfect Thatcherite dyarchy: duty and privilege. You should do something, and you should value your ability to do so. And this on an individual level, without the overbearing intrusion, let alone the positive discouragement, of the machinery of state.

Then she moved on to another critical proposition of free market economics, that the prosperity of a company affected not only those who owned the business but those who worked for it and therefore derived their incomes from it. Everyone depended on the success of private capital. Healey, she implied strongly, either could or would not accept that principle because his political world view was shaped around an overarching state.

It affects not only the few who have built up the business but all those who work in it. They will naturally be worried that the business cannot carry on under the same ownership. It will soon not be possible to sell the shares to pay duty. The only buyers then will be the bigger companies or the State. That is what the right hon. Gentleman wants. He wants such companies to be taken over by the State, and taken over easily.

Nor was it simply private capital which played a central role. For Thatcher, with some of her views shaped by a kind of stern Victorian liberalism imbued in her in her childhood home in Grantham, mutual assistance between individuals and the operation of private philanthropy was far preferable to the enforced charity of state hand-outs. “The Chancellor would prefer to see all beneficence come from the State and not from private charities,” she declared, which rather hit the nail on the head in her view.

Thatcher also felt that Healey was guilty of bad faith, which, in her rather stark and unyielding moral sense, was deeply distasteful.

That is the first time we have had a Chancellor putting a tax on a good turn. It was not foreshadowed in the White Paper [on Capital Transfer Tax]. It will affect many employees whose employers lend them money to buy a house at no rate of interest or a very low rate. They will be caught under this tax.

The idea of the Capital Transfer Tax was anathema to Thatcher. For her it was the rapacious hand of the state, reaching as far as it could to take away hard-earned capital. It was overbearing and it was interfering, and it inserted the state into a space where individuals should be allowed to earn, save and gift as they wished. “Let us keep the successful here instead of driving them abroad,” she concluded. “We shall oppose this clause.”

The House continued its consideration until well after 1.00 am. It had been another strong performance on Thatcher’s part. Not only was she able to deal the government several decent blows, but she had been able to identify some critical ideas and phrases, and she had begun, ever so tentatively, to map out a philosophical framework which was noticeable different from that which the government was assembling. This was not Thatcherism yet, but it shared some of its DNA.

The committee resumed shortly before 4.00 pm the following afternoon. These were times of hardier or more long-suffering Members; sitting into the small hours was in no way unusual, and was regarded as an ordinary part of parliamentary life. Moreover, the opposition was keenly aware that one of the few weapons available to it, even when the government had a slender majority, was delay. It could make government MPs work harder than they liked and sit for longer, and on all sides this was understood as part of the rhythm of business.

John Nott (Con, St Ives) opened for the opposition. In his early 40s, he had been a regular officer in the 2nd Gurkha Rifles during the Malayan Emergency before going up to Trinity College, Cambridge, to read law and economics. He was then called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1959, before being elected Member for St Ives in 1966. He had been minister of state at the Treasury for the last two years of the Heath government, but the scale of disenchantment he had experienced radicalised him and he became a fervent monetarist, taking responsibility for the banking and insurance industries and the technical aspects of monetary policy when the Conservatives went into opposition.

Nott set about the Capital Transfer Tax afresh, and asked that the matter be referred to the select committee on the wealth tax which had been set up the previous month to consider the government’s proposals and report in time for measures to be included in the Finance Bill in 1976. The government had conceded this form of scrutiny partly as a delaying measure, after adverse press the previous summer over the likely economic effects of a wealth tax. (In fact the idea would end up being shelved permanently.)

By the evening the chancellor and his shadow were both in their places. It was now that Healey, who could always spot a bon mot as well as a flagrant insult, was able to try out some of his best lines on Thatcher. His wind-up was a robust partisan performance, resented by some Members, but Healey had only ever had one mode of disquisition. He tried to characterise Thatcher, and her party more generally, as being on the side of wealthy individuals.

The hon. Member for Gainsborough [Marcus Kimball], I think it was, described the right hon. Lady as “the blessed St. Margaret”. The fact is that she emerged in this debate as La Pasionaria of privilege. She showed that she has decided, as the Daily Express said this morning, to see her party tagged as the party of the rich few.

Some Conservative Members sought the intervention of the chair, but Alan Fitch (Lab, Wigan), a member of the Chairman’s Panel of senior backbenchers, was having none of it and pressed ahead with the business. Thatcher had her opportunity to respond to Healey, and Fitch may well have taken the view that she needed no special protection from him.

She began with one of her most withering attacks on Healey, one which would be remembered for years. In a magnificently not-angry-just-disappointed tone of voice, she did her best to shred Healey.

I wish I could say that the Chancellor of the Exchequer had done himself less than justice. Unfortunately, I can only say that I believe he has done himself justice. Some Chancellors are macroeconomic. Other Chancellors are fiscal. This one is just plain cheap. When he rose to speak yesterday we on this side were all amazed how one could possibly get to be Chancellor of the Exchequer and speak for his Government knowing so little about existing taxes and so little about the proposals which were coming before Parliament. If this Chancellor can be Chancellor, anyone in the House of Commons could be Chancellor.

It was a good attack, sardonic rather than humorous (for she had no skill for the latter). And it suited her rather righteous, stiff-necked attitude, so different from Healey’s minatory bonhomie. It is certain the chancellor will not have taken offence, but again it showed an opposition spokesman always on her toes, always looking to land a punch. Moreover it showed someone unafraid of any Labour big beast. She carried on in the same vein. “I had hoped that the right hon. Gentleman had learnt a lot from this debate. Clearly he has learnt nothing.”

She then launched a barb that was to become characteristic of Thatcherism, and an inversion of the received wisdom of the two major parties. The tax the government wanted to introduce, she asserted, “will affect not only the one in a thousand to whom he referred but everyone, including people born like I was with no privilege at all. It will affect us as well as the Socialist millionaires.” That was a courageous swing. Healey was hardly redolent of middle-class privilege: his father was an engineer who had earned a scholarship to the University of Leeds and become a headteacher, while Healey himself was a grammar-school boy who had won an exhibition to one of the grandest and most cerebral Oxford colleges, Balliol. The chief secretary, Joel Barnett, was the son of a Jewish tailor in Manchester and had qualified as an accountant. They had risen on the strength of their considerable merits.

Yet Thatcher was able to leverage her own relatively humble origins, the daughter of a grocer, it was true, but one who had been a Methodist preacher and mayor of Grantham just after the war, to stand with the ordinary man and woman against a government which, she suggested, neither understood nor cared about their quotidian anxieties. It would be a much more familiar narrative a decade thence, but some might reasonably have raised an eyebrow if they had looked at, for example, Robert Carr (Westminster School, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge), whose family ran a metal engineering business, or another Conservative who had just spoken, Nicholas Ridley (Eton and Balliol College, Oxford), the younger son of a viscount who was a civil engineer and company director.

She was back on her feet shortly before 9.30 pm. Responding to Barnett, she began impatiently and in a manner which oddly foreshadowed the language and mood of Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn’s 1980s comic masterpieces Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister. Barnett had told the House that tax reliefs would be kept under review, but Thatcher was impervious to this kind of bland assurance.

I know full well that when a Minister has not a clue what to say he will say that he will keep the matter under constant review. It does not mean very much… It is a standard, stock reply. “Constant review” often means no review at all.

She emphasised that tax rates must be re-examined regularly by Parliament, not simply by the Treasury or the Inland Revenue. Alas this was a dedication to legislative scrutiny which would fade as her career progressed.

The debate continued into the small hours, other Conservative frontbenchers taking up the fight. But Thatcher was clearly still present, as she intervened occasionally. She spoke briefly, at about 1.45 am, on amendments 66 and 67 (local loans), after which the committee reported the bill to the House, ending the Committee of the whole House stage.

It was a demonstration of Thatcher’s punishing professional schedule at this point that on the day of the first ballot for the Conservative leadership, once Thatcher had declared a challenge to Heath, she was busy in standing committee. On 4 February, in a shock to the party, the media and the world, she outpolled the incumbent, gaining 130 votes to Heath’s 119, the eccentric Scottish aristocrat Hugh Fraser (Con, Stafford and Stone), who had stood for reasons which were mysterious to everyone, collected 16. Airey Neave, as Thatcher’s campaign manager, held a celebratory party for her in his flat, but she had not won outright; while Heath had been defeated, and holed below the waterline (to use a metaphor he would understand), her winning margin was too small to decide the leadership. A second ballot would be held a week thence. Meanwhile, Thatcher dined with the Neaves, then returned to the Commons for the Finance Bill standing committee, where she was occupied until 2.30 am.

The second ballot was 11 February. Heath having withdrawn, Whitelaw entered as the Heathite establishment candidate, but Jim Prior, Sir Geoffrey Howe and John Peyton also entered the lists, none of them really with a credible candidacy. Thatcher’s momentum was irresistible. She received 146 votes to Whitelaw’s 79, an emphatic win, while Prior and Howe each received 19 and Peyton trailed the field with 11. Neave had installed Thatcher and her parliamentary private secretary, Fergus Montgomery (Con, Altrincham and Sale), in his Commons office, where he found them to tell her that she was now leader of the Conservative and Unionist Party. The next day, the standing committee met again, and Thatcher had not yet appointed a new shadow team so arrived to continue her work. When she came into the room at 10.25 pm, she received a standing ovation from Conservative and Labour MPs. Barnett said “I am sure I speak for all my friends on this side of the committee when I say I hope Mrs Thatcher will continue as Leader of the Opposition for very many years”, to which there was laughter.

Report stage of the Finance Bill would not come until later in February 1975, after Thatcher had become leader and appointed a new shadow Treasury team led by Sir Geoffrey Howe (Con, East Surrey). There were procedural dramas to come, including Nigel Lawson (Con, Blaby) asking for a debate on the specific measures on forestry and farming under the provisions of Standing Order No. 9. There would also be complaints from the opposition about the late tabling and printing of amendments for report stage (on Friday 28 February the House only had access to a limited number of photocopies of an unmarshalled list of more than 700 amendments, which was clearly impossible and unacceptable). But for Thatcher they were, to a large extent, someone else’s problem.

If one accepts the argument that Thatcher was not merely an empty vessel into which Neave poured his desire for revenge against Heath, it is also abundantly clear that Thatcher herself became a highly credible candidate through hard work and determination. Timing was in her favour; as Heath’s leadership disintegrated, she was at that precise time on the opposition’s firing step, taking well-aimed shots at the government. At this point, the electorate which chose the party leader was the parliamentary party, and it was to this group that she was so prominently displayed and exposed, not only in standing committee but in the chamber too. For all that her appointment as shadow chief secretary had been a demotion—Lawson’s back end of the pantomime horse—it had also been the best opportunity Heath could have given her. Literally no other portfolio, not even shadow chancellor, would have been as advantageous.

However, it was not merely fortunate timing. Thatcher used the platform brilliantly. She displayed a mastery of detail, a tenacious debating style which was unafraid of any minister, and a grasp of something like an alternative policy, one which was designed to appeal to ordinary voters and would reward thrift, prudence and hard work. It was a perfect match of required skills and candidate, and evidently the word went round that Thatcher was more than capable and should be in people’s minds when they considered who might replace Heath.

It is a striking irony of this turn of events that it was a near-exact repeat of Heath’s own journey to the leadership a decade earlier. In the wake of the 1964 general election defeat, Sir Alec Douglas-Home had put Heath in charge of policy planning, but in February 1965 he switched him to be shadow chancellor, replacing Reginald Maudling who had failed to sparkle. It was with the Treasury brief that Heath led the opposition’s fight against the Finance Bill in 1965, shaking off—to some extent!—a reputation for stilted and wooden delivery in debate and showing himself dynamic and fearless. When Home stepped down as leader that summer, Heath beat Maudling to the position, not least because of his enhanced reputation.

Thatcher was never a great orator. Although she was a tenacious and skilled debater, able to marshal and use facts with impressive ease, she was never a “great parliamentarian”, and when she produced memorable phrases they were often written by others and she did not have a natural felicity for wit, humour or lightness of touch. Of course she was not the finished product in February 1975; she had a long way to go to become the dominant, majestic who in October 1990 would exclaim “No! No! No!” to the House of Commons as a useful shorthand for her views on the European Community. But the solid foundations were there, and they made a significant contribution to her succeeding as party leader when she challenged Heath.

There was one other quality which had shone through in her role regarding the Finance Bill, which would often sustain her in her leadership and later her premiership, and would, ultimately, make a substantial contribution to her downfall. She was fearless and possessed of iron-clad self-belief. It had shown in her disdainful dismissal of Denis Healey (“plain cheap”), who was probably the most robust debater in the cabinet, and in the consistent and logical articulation of a general economic outlook which contrasted with that of the government. And it showed when she became party leader: she was asked how she felt about taking on the old wizard Harold Wilson across the despatch box, and responded calmly “About the same as he feels facing me, I should think”. It was a good response.

This is not a breathless paean to Margaret Thatcher. Although chronologically I am largely a child of Thatcherism—I was 18 months old when she entered Downing Street—I have never been an uncritical admirer. She had some truly exceptional qualities including clear-sightedness, determination and a voracious appetite for hard work, and she was an absolutely necessary counterbalance to the declinism of the 1970s. Much of what she did was right, and her medicine, if sometimes unpleasant, was often vital for the nation’s well-being. But there were aspects of her character I find off-putting, such as her fanaticism and her vague sense of anti-intellectualism, particularly when it came to arts and culture, and her political judgement when it came to people could be poor.

Nevertheless she was easily the most transformative Conservative leader between Churchill and Cameron, and it is important to understand how she went from a largely ignored former education secretary to leader of the party within a calendar year. Some of the cards fell her way, and some of them tipped far enough for her to be able to move them herself. But she showed nous, talent and determination in exploiting the opportunities she was given. Her rise to the leadership may not have been predicted, nor even wholly predictable, but she dealt with the circumstances better than senior and more experienced colleagues, who were often left exasperated and nonplussed by her triumph.