Leading the Conservative Party: what qualities do you need to have?

We can guess at likely candidates for the Conservative leadership but no-one has declared yet: so what are the characteristics and talents we should look for?

Introduction: the landscape of defeat

I knew the overwhelming likelihood was that the Conservative Party would lose the general election. If the result had been anything else, it would have been the biggest upset for popular expectation and opinion polling in history. Anything can happen at backgammon, of course, and there was always a more-than-zero chance the unimaginable would transpire, but, much more than I was as a 19-year-old undergraduate at the time of the party’s last ejection from office in 1997, I had begun to prepare mentally for the disappointment, shock and—this is not a ridiculous word to use—trauma of defeat.

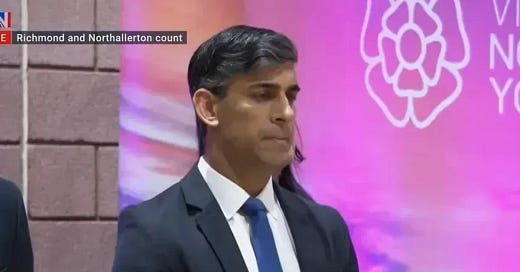

Just as defeat was the almost-certain outcome, so it followed that Rishi Sunak would step down from the leadership of the party. Our political culture now is unforgiving, and if you lead one of the main parties to electoral defeat, you are rarely given a second chance: since the departure of Edward Heath in 1975 (he lost three of the four elections in which he led the Conservatives, yet was still surprised and bitter when he was ejected), the only leaders to be given the benefit of the doubt have been Neil Kinnock after 1987 and Jeremy Corbyn after 2017. It’s a rough game but everyone is a volunteer. So even if he had wanted to, and there was little sign of that, Sunak would not have been left unmolested at the head of the party.

The Conservative Party had already changed leader in 2016, 2019 and twice in 2022, so leadership contests were becoming familiar exercises. Speculation about who might take the helm in the event of defeat had been widespread for more than a year, and some senior ministers were judged almost daily through the lens of what significance their actions had in relation to a pitch for the top. It was clear to me that my preferred candidate was Penny Mordaunt, whom I know well, but it was also no secret that in the event of a heavy defeat, her Portsmouth North majority of 15,780, which would usually be a comfortable margin, placed her in the danger zone. So it proved: in the end, despite a tireless local campaign, she lost by just 780 votes to her Labour challenger, Amanda Martin. I was and am bitterly disappointed, but I knew it was a realistic possibility.

Of course Penny is not the only possible contender whose progress has been arrested for the moment by the electorate. Eight full members of the cabinet and four ministers “also attending” lost their seats, including the Defence Secretary, Grant Shapps (Welwyn Hatfield). He had been touted as a potential runner, while Mark Harper (Forest of Dean), Transport Secretary, had stood for the job in 2019 (although he had come second last). Although it was an unlikely eventuality, Liz Truss’s defeat in South West Norfolk rules her out of any formal role.

That leaves me on the open market, as it were, uncommitted to anyone’s cause and waiting to see what the choice looks like when the contest is finally held. The timing is uncertain: we know that the field will be gradually slimmed down to a final two by the parliamentary party, after which the whole membership will choose between the finalists, but the fine detail will be decided by the 1922 Committee, which met on Wednesday 10 July to elect its chairman and executive (I explain this body here). Sir Graham Brady (Altrincham and Sale West) had chaired the committee since 2010 but stood down from the House of Commons, and Harrow East MP Bob Blackman defeated Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown (North Cotswolds) by 61 votes to 37 (though there was some controversy over the organisation of the voting).

The timing of a leadership election

Opinions vary on when the leadership contest should take place. In terms of duration, it is to a degree dependent on how many candidates are nominated: in 2022, there were eight candidates, while 10 stood in the 2019 contest, and five initially took part in 2016 (though the membership vote did not take place as Andrea Leadsom withdrew after reaching the final two, leaving Theresa May unopposed). The 2022 election took seven weeks, roughly the same as the 2019 iteration, while the truncated 2016 race only lasted a fortnight. But when should the formal process begin?

There are essentially two schools of thought. The first argues that the party can make no real progress until a new leader is in place, and will be a less effective opposition so long as it has an outgoing and hobbled Rishi Sunak and an interim shadow cabinet. However, a counter-argument runs that potential candidates should be given a while to adjust to opposition: only a fifth of current Conservative MPs have ever sat on that side of the House. Assuming that most of the likely challengers are already on the front bench, delaying the contest until some time in the autumn will give them the opportunity to show their skills as shadow ministers. This may be particularly important as 26 of the 121 Conservative Members are new and have never seen their colleagues at close quarters before, so may value a period of time to assess them.

The model cited for this second argument in the leadership contest of 2005. After the election of 5 May, which Labour won easily, Michael Howard, leader since 2003, announced the following day that he would not take the party into the next election as he was by then already 63. He said that he would provide an opportunity to review the rules for leadership contests but stand down “sooner rather than later”, and he reshuffled the shadow cabinet to include potential younger candidates for the succession. George Osborne became shadow chancellor, Liam Fox was moved to be shadow foreign secretary, David Willetts took on trade and industry, David Cameron was appointed shadow education secretary and Sir Malcolm Rifkind, returning to the Commons after eight years away, became shadow work and pensions secretary.

A consultation paper on reforms to the way the Conservative Party worked was circulated by Howard at the end of May but rejected by the Constitutional College in September. That at least allowed the leadership contest to begin: nominations would open on 7 October, MPs would whittle candidates down to the final two and the membership would vote before 5 December, with the result announced the following day. This allowed the party conference in Blackpool at the beginning of October to act as a platform for the would-be leaders—by that stage, David Davis, Cameron, Fox, Rifkind and Kenneth Clarke—to make their pitches to party members. Cameron, of course, emerged victorious on 6 December, concluding a process which had lasted seven months from Howard’s initial announcement.

I see the value in allowing candidates to stretch their legs in opposition, but I think waiting until the end of the year to choose a new leader is too long a delay. My own preference would be for a process which produces a result just before this year’s party conference in Birmingham, beginning on 29 September. That would allow the new leader to use the conference as a launchpad for his or her stewardship of the party. Of course there is the unknown factor of Parliament’s sitting times over the summer: the House of Commons was scheduled to rise on 23 July and the Lords two days later, but there were suggestions in the media that Sir Keir Starmer might keep both Houses going until the beginning of August to give his ministers as much time as possible to begin work on new policies. The State Opening of Parliament only took place today, Wednesday 17 July, and the summer adjournment may therefore be squeezed to only a few weeks. We will know soon enough.

Executive search: what does the ideal leader look like?

Since there are currently no declared candidates, and I have no committed preference at this stage, I want to look not at the potential contenders at this stage, but instead at some of the qualities a leader of the Conservative Party—and leader of His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition—under the current circumstances should possess. I would not expect to find them all wholly embodied in any one candidate, and this is partly the construction of a Platonic ideal, but there is value in having some kind of metric when a field does begin to emerge.

Humanity

You could attach all sorts of labels to this quality, which I think may be the most important of all, but what I mean is the ability to communicate with the public in an unforced, natural way, to establish a connection of trust and respect. To be blunt, we desperately need a leader who can “do human”. I don’t mean that the party should simply choose a plausible salesman; it is much more profound than that. Acknowledging that politicians in general are disliked and distrusted, that the political system is believed to be ineffective and that Conservatives in particular are weighed down by a legacy of scandal and policy failure, there is a distance between politicians and voters which is draining energy and credibility from our public life.

There are many reasons for this. The increasing prevalence of MPs who go from university to advisory or staff jobs with political parties and think tanks before finding nominations for safe seats in Parliament is believed to have created a cocoon around too many politicians, isolating them from the priorities, concerns and experiences of voters. There is some truth in that: of the new cabinet of 22, eight come from a broad political advisory or party background and two were trades union officials. That is not to meant to favour the Conservatives, as the 22-member shadow cabinet contains six people who had political or advisory roles and four who worked in the financial sector, although nearly a third worked in private enterprise of various kinds.

A more important factor in demonstrating this sense of isolation, of a separate political class, is, I think, the way in which politicians talk and attempt to communicate. This stems, of course, partly from the number of senior MPs who have spent their whole careers around government, Parliament and political parties. But it struck me with renewed force earlier this year, as I described in my weekly City A.M. column. It was prompted by the Labour Party’s production of their “campaigning bible” for parliamentary candidates, a verbal and data resource on which aspirants can draw. I said that it:

teems with slogans and punchy phrases which activists can use to hammer home a consistent, coherent, disciplined message. The slickness, the calculation and the straightforwardness are in some ways the final triumph of New Labour, the culmination of everything that Sir Tony Blair and Lord Mandelson worked so hard to create 30 years ago.

My argument is this: while the communications gurus in all political parties work tirelessly to condense complex policy ideas into memorable slogans only a few words long, and believe that with relentless repetition these slogans will stick in voters’ minds and therefore influence their voting behaviour, something else is happening. What they intend to be message discipline in fact limits and distorts the everyday language of politicians, robbing them of spontaneity, natural expression and an ability to engage with each other. It reduces their public utterances to disjointed ejaculations of catchphrases which lose meaning with every repetition. As I said in January:

Voters now hear politicians using a register which has become remote and artificial, so unlike the way that people talk in real life that it is inauthentic and cynical. It is as if we can now see the joins: the way which slogans are designed to elicit a specific response is obvious, and that robs the trick of its magic.

The consequence of this strange, distorted style of communication is to make politicians seem unable to engage in dialogue in normal way. Instead they “look self-absorbed, deaf to arguments and evasive”. If you are sceptical of this proposition, (re)watch any of the television encounters between Rishi Sunak and Sir Keir Starmer during the general election campaign. It is true that they make a pair of unusually uncharismatic leaders, but even so they seemed forced, rehearsed, robotic and lacking in warmth and spontaneity. I was reminded of A.A. Gill’s (unkind) remark about the Japanese, which is in fact more apposite for our political class: “the people that aliens might be if they’d learnt Human by correspondence course and wanted to slip in unnoticed”.

This is the habit a new leader has to break. We need a candidate who speaks fluently but not glibly, with conviction and authenticity, someone who has natural warmth and charisma. This is a substantial challenge, as television and radio can act as a filter and blunt the personalities of otherwise-dynamic politicians, and it also requires a degree of deprogramming. We all have bad habits and platitudinous verbal tics which we would rather not use but can fall unconsciously into our speech patterns.

It is worth saying that the quality I am trying to describe here is not the same as “relatability”, a currently popular concept but one I have very little time for. This weekend Jo Ellison wrote a column in The Financial Times which praised the new Deputy Prime Minister, Angela Rayner, as “the most relatable MP I’ve ever seen”. I realise that Ellison is writing in a relatively light-hearted spirit and I don’t share some of the sharper, often harsher, criticisms often levelled at Rayner. She seems to me at heart a dedicated, well-intentioned, politically savvy woman whose appearance a few months ago on Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell’s Leading spin-off from the podcast The Rest Is Politics showed her to be quietly impressive, thoughtful, open and self-aware.

Ellison and I overlap slightly in that she describes Rayner at one point as “a welcome dose of human in a cabinet of ruthlessly uptight”. But she frames this in a matey, slightly mimsy narrative which is very different from my conception.

Rayner recalls every other sleep-deprived mother (or, like her, grandmother) trying to rouse some action on the PTA: her bronze eye shadow might be brassy, and her wacky lipstick smudgy, but by God she’ll have you volunteering for a shift on that tombola at the school fete next weekend.

I don’t want politicians to be “relatable”, particularly. I have no interest in their “ordinariness” or the extent to which their personal lives might be rackety or chaotic, as if that makes me feel better about any racketiness or chaos in my own. I’m more than content for those who seek high office to be more impressive, more organised and more focused than I am. I don’t expect or want them to come from the same kind of background—or, indeed, a different background; I’m indifferent—but I would like the next Conservative leader to be able to speak clearly, incisively and persuasively, to understand the danger of falling into Westminster and Whitehall jargon and group-think, and to demonstrate the ability to take a step back and measure policies and rhetoric against the milieu in which ordinary voters exist.

I want a leader who recognises the mangled, obscurantist meaninglessness of “starting the work on driving growth” and “mission delivery boards to drive through the change that we need” (Starmer) or “launching a bold plan to make science and technology our new national purpose” and “bold action and a clear plan… [to] create a secure future” (Sunak). It is not a matter of dumbing down: voters are not stupid but they are impatient, sceptical and uninterested. But principles and policy can be expressed in a variety of ways which resonate, and which can inspire, without being cloaked in disjointed, staccato vacuity that is simply not a way in which anyone actually talks. A leader does not need to be the same as the electorate, but he must be of the same species.

Buoyancy

Whoever is elected to succeed Rishi Sunak has a long, hard slog ahead. Having lost a general election by a catastrophic margin and been reduced to only 121 MPs, the Conservative Party is relegated to relatively political irrelevance for a while. As John Major said in his farewell to the party conference in 1997:

It’s difficult being the leader of a newly defeated party. For a while, people won’t wish to listen to what we have to say… We now have the luxury of time to think anew—and we should use it to build up policies that the broad mass of the British people will know are right—and feel comfortable with.

This, of course, requires humility, and any sane Conservative should not find it challenging to bring that emotion to the surface. Whatever observations might be made about Labour’s victory—that it was achieved on a share of the vote not even two per cent larger than Jeremy Corbyn won in 2019, that it was enabled by a manifesto stripped almost bare of tangible commitments, that it reflects an electoral coalition which is “broad but shallow”—should be made by commentators, analysts and scribblers, not by the Conservative Party. You play the game by the rules of the time and abide by the result, a fundamental tenet of the democratic process. We must not seem either poor losers or, worse, unable and unwilling to absorb the scale of defeat.

This humility must, however, be accompanied by a resilience and inner strength. Week after week, the new leader will have to face Sir Keir Starmer across the dispatch box at Prime Minister’s Questions, in a House of Commons dominated by the Labour Party. That will be thankless and gruelling, as William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard at least will tell you. Even if the next leader is demonstrably better and more mentally and linguistically agile in these encounters, it will make no difference. Hague was commonly agreed to have been a better debater than Tony Blair, and Blair was acutely aware of it, but in the broad sweep of history it made no difference. After four years, the Conservatives gained one seat overall at the 2001 general election, and their share of the vote rose by one per cent.

Despite that, these weekly clashes matter for the morale of the parliamentary party, and they matter for the general tenor of the party’s image. The leader of the opposition must go into PMQs every week poised, positive, punchy and confident. It would be disastrous if the next leader seemed at any point despondent, or looked like someone who had already given up.

This is one facet of a wider disposition. History and psephology tell us that it is almost impossible for the Conservatives to hope to return to government after one parliament in opposition, in 2028 or 2029. “Almost” but not completely: Labour’s transformation between 2019 and 2024 was “unprecedented”, the vaunted Attlee government ran out of steam and almost lost its majority after less than five years, and the Liberal landslide of 1906 disappeared into parity with the Unionist opposition at the first election of 1910. “Unprecedented”, a word beloved of political journalists, simply means that something has not happened before. It gives no indication of why or what the likelihood is, or, as Rory Sutherland puts it in his brilliant Alchemy, “it’s important to remember that big data all comes from the same place—the past”.

We can all accept that a government with a majority of 174 being ejected after one term is unlikely, and a Conservative leader would seem unrealistic if he insisted that the party’s whole focus was on winning in 2029. But he must seem quietly confident that there is scope for significant progress and that better times are ahead. After all, if the leader of the opposition does not believe in the party, why should anyone else? There will be crises of confidence, such as the one suffered by Starmer when Labour lost the Hartlepool by-election in May 2021 and he contemplated resignation, but, as Starmer did, the leader must make these purely private affairs.

In this parliament, opposition will be in many ways a ritualistic affair. The government will not be defeated in the division lobbies, yet the Conservative leader must be at the head of his 120 colleagues day after day, night after night, registering formal dissent in the face of massive majorities. Amendments must be tabled to bills in the certainty of rejection, public bill committees must have a functioning opposition, ministers must still be questioned on the floor of the House. These may be empty habits now, but they will not always be so. The leader must set an example and show quiet confidence that every day will be a little better than the last; not reckless exuberance or a detachment from reality, just a resilience and buoyancy which says to colleagues, and to the electorate, “We can do this”.

A sense of purpose

Leadership is a role on which whole libraries have been written over the years, and we are always trying to learn lessons and transfer virtues from one sphere to another. In politics, it is not always successful, because the traits required for leadership of a party in a parliamentary democracy are varied, ever-shifting and sometimes almost contradictory. Most frequently expressed is a desire to bring the habits of the private sector, of business leadership, into politics, about which I wrote in October 2022. Rishi Sunak was, after all, the first prime minister to have an MBA, though it did not seem to help him greatly (the only US president similarly qualified was George W. Bush). And the list of successful businessmen who have smashed themselves on the rocks of politics is hardly short: John Davies, Archie Norman, Gus Macdonald, Shriti Vadera, Digby Jones, Jim O’Neill, Mark Price. None achieved as much as they might have hoped, and most walked away again.

This means that when I say the next leader of the Conservative Party must be decisive, I immediately have to qualify or define that. Politics is a team sport, and any team works best when each member is fully committed and feels valued and respected, so the leader must be collegiate and consultative. The shadow cabinet must be a genuine forum for discussion, and no-one should feel unable to express themselves freely: the condition of the party is such that we cannot throw ideas and contributions away unexamined. The same is true of the 1922 Committee, the party’s board and various policy groups: all must feel they can contribute freely and openly, and that they are valued.

The trick of successful political leadership is knowing when and how to draw that consultative process to a close and make a decision. Thereafter the required qualities become quite different: once a conclusion has been reached, it should be defended and enforced. We cannot have endless arguments over policy, with leaking and counter-leaking, and those on the losing side constantly seeking to re-open the debate. Healthy, robust, free-speaking discourse must be followed by determined decision-making and loyal acceptance of the party’s policy and approach. In short, the new leader must consult, decide and enforce.

This is by no means easy. We are bombarded by caricatures of past leaders: the autocratic and friendless Heath, the dogmatic and unyielding Thatcher, the vacillating and indecisive Major, the don’t-sweat-the-small-stuff instincts of Cameron, the directionless, eager-to-please Johnson. None of them is wholly false but none is wholly accurate either. Thatcher became remote and unwilling to listen in her later years but at the height of her premiership relished fierce, well-informed argument with ministers. As Kenneth Clarke, who served in her cabinet from 1985 to 1990, recalled:

She loved political rows. She was extremely combative, but then, so am I. It was great fun if you could stand the hassle… she could be extremely rude if she disagreed with you. She was unbelievably persistent… she used to drive me up the wall sometimes.

Yet he rated her, with Clement Attlee, as one of the two greatest peacetime prime ministers of the 20th century.

Conversely, John Major deliberately adopted a more consensual style when he succeeded Thatcher in November 1990, an absolute necessity given the significance of her apparent imperiousness and unwillingness to concede had played in her downfall. As the late Hugo Young noted, the Conservative Party “wanted Thatcherism pursued by non-Thatcherite means”. Major began his first cabinet meeting by saying “Well, who’d have thought it?”, while one minister—I cannot now find a reference—compared his colleagues to the Hebrew slaves in Verdi’s Nabucco. (I have written about the early days of the Major premiership here.)

I talked about the Platonic ideal, and in terms of purpose the model would be a leader with the decisiveness of Thatcher, the collegial spirit of Major, the wit and charm of Macmillan and the sheer amiability of Douglas-Home. That may be an impossible ambition, but it gives the party and its chosen candidate something to aim for.

Intelligence

This last quality should be taken as read if a model political leader was being sketched out, but the British electorate has always had a vague suspicion of intellectuals and the intelligent, summed up in the Marquess of Salisbury’s damning and idiotic condemnation of Iain Macleod as “too clever by half”. Politicians are, in some respects, surprisingly representative of the population, which means that they range from a very few unquestionably brilliant minds to some genuinely stupid people with the majority sitting somewhere in the middle.

Ed Miliband was sometimes characterised as an intellectual, and he certainly immersed himself more deeply in the detail of policy than most party leaders (though ultimately without success), while Roy Jenkins and Tony Crosland were genuinely powerful intellects (as was Harold Wilson, though perhaps in a narrower sense). Thatcher was fiercely intelligent and remorselessly questioning, though some of the heavy ideological lifting of what became Thatcherism was done by Sir Keith Joseph (and, before him, avant la lettre, by Enoch Powell), as well as Angus Maude. You could identify Conservative Miliband equivalents, dedicated policy wonks, in David Willetts, Oliver Letwin and perhaps Jo Johnson. Of the surviving Conservative MPs—and this is not endorsement of or encouragement to a leadership bid—Jesse Norman, Danny Kruger, Julian Lewis and Nick Timothy stand out as capable of deep and analytical thought, admittedly across the spectrum of opinion within the party.

The recovery of the Conservative Party from the low point of 4 July 2024 will require a great deal of organisational and institutional change, as James Price recently argued in The Critic. But it will also need to be a work of ideology and ideas, as profound as the one the party undertook after 1945. As I explained a couple of weeks ago, we should not be afraid or ashamed of ideology: it is the glue that binds policies together, the framework of intellectual coherence in which individual proposals are set. This time there must be a twin-track approach: we must examine our basic ideas about the world, but also examine where we have professed them in the past but fallen short, and understand why. It is not a matter of a blank slate but of a re-examination of the instincts and philosophy of the kind of conservatism that has proved so effective, in office as well as electorally, over the past 150 years.

To lead this does not require a professor of political science or someone who has read every last word that Smith, Burke, Hayek, Kirk, Friedman, Popper and Scruton wrote. (It would be a positive advantage if they had not read Dorries or Truss.) But we will require someone with imagination, intellectual curiosity, breadth and agility to work with political philosophy and be at home debating ideas. The leader will have to convincing when explaining the Conservative vision and its underpinnings to the electorate, and that will require not only the communication skills I talked about under “humanity” but also an authentic seriousness and sense of conceptual ease.

Building the perfect beast

As I made clear, I have no attachment at this stage to any likely leadership candidate. At the time of writing, shadow security minister Tom Tugendhat is thought almost certain to stand, as is shadow housing and local government secretary Kemi Badenoch, while it is reported that former home secretary Dame Priti Patel intends to offer herself as a candidate. There is a growing feeling that Suella Braverman’s hopes, never in my view great, are fading fast, but her former deputy, Robert Jenrick, has been mooted since before the general election. However, on the basis of the last two leadership elections in 2019 and 2022, there may be some wild cards: remember the aspirations of Sam Gyimah, Kit Malthouse, Steve Baker, Bill Wiggin and Rehman Chishti?

That means I offer these suggestions in all impartiality, not tied to a candidacy. I think they will all be necessary for a new leader to make significant progress in helping the party recover, whether that leader turns out to be the next Conservative prime minister or a more transitional figure.

(It was striking at the time that until William Hague assumed the role in 1997, the only Conservative leader of the 20th century never to be premier was the luckless Austen Chamberlain, who “always played the game and always lost it”. He was a stopgap leader in 1921-22, having been a Liberal Unionist until the two parties merged in 1912, though to his credit had he acted differently he might well have become prime minister in 1922 or 1923. After Hague’s four-year tenure, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard also led the party without ever crossing the threshold of Downing Street.)

Let me make it abundantly clear, because my cynical instincts can see this coming, that I am not arguing here for some centrist managerialism, stripped of any ideas or principles. Quite the opposite, I have said repeatedly that ideology is the lifeblood of politics and we should never be ashamed of it, instead using it to systematise our ambitions. I have a bugbear about film reviews which complain that the film isn’t about what the critic wanted it to be about, and in a similar vein, this essay is about personal characteristics, not ideology. Take it on its own terms: it does not claim to be exhaustive and will very much not be my last word on the subject.

The choice of leader is, of course, shared by two very different electorates. It is the 121 remaining Conservative MPs who will nominate candidates, make an initial assessment of them and narrow the field, if necessary, to two. Then it will be for the party membership, 172,437 at the end of the summer of 2022 but very possibly smaller now, to decide which of the final two candidates should lead them. I don’t expect them to have read this essay, but I do hope, very fervently, that they are entrusted with a decision which has consequences far beyond their own numbers, and that they think deeply and choose wisely.

Who in God's name would want the job? It's pointless futile painful and dreadful. And that's in good times. Now through combination of appalling circumstances beyond its control, pandemic & ukraine, plus self inflicted injuries Truss and Partygate, the tories are condemned to years of opposition. It might never recover. Reform the libs and greens might split the bipolarity in England forever, the nationals in Wales and Scotland have already done so. Voters are now no longer bound by class. Some remain fiercely tribal many like me are ruthlessly mercenary, putting their vote in who looks least awful today. I've no fixed loyalty. They certainly have none to me. I'm looking forward to watching the working class hating snobs in the tories squirm in opposition like Mitchell and good riddance to Clark may and Cameron forever. At least lab feel and smell like they actually care and try to help. The tories deserve this, they've largely brought it on themselves.

I'mnot sure anyone would want to take on the job given it might be a long-term responsibility with no likely success until well after 2029. Historically, failing leaders (beaten at a general election) resign leaving the role to others. Perhaps Badenoch will bide her time before applying?