The men in grey suits: the 1922 Committee explained

We hear a lot about the Conservative Party's parliamentary group when there is a leadership crisis, but how do they influence events?

I was considering what to tackle next for this series of essays. I am at the moment rather fixated by the House of Commons, and I make no apology for that: I have been fascinated by it for most of my adult life, I worked there for more than 10 years, and it is, despite all anxieties to the contrary, still the central arena of our national politics. Its procedures can have a huge impact on current events, its support is the prime requirement for a British prime minister, and if we are ignorant about it we are ignorant about the news.

A very old friend, who is politically aware but not an obsessive, suggested I might write something about the 1922 Committee. This is the gathering of the Conservative parliamentary party which represents the feelings of backbenchers and had a pivotal role in the choice (and removal) of leaders of the party, as we have seen more often recently than we might have expected. It struck me, after a moment’s thought, that this might be helpful for some readers, so here we are.

Any government depends on the support of its own backbenchers. It is therefore a truism that any government must have some way of maintaining a consultative relationship between ministers and the foot-soldiers on whom they rely for control of the elected House. The Labour Party, blissfully wedded to internal structures, power balance and byzantine wranglings, performs this function through the Parliamentary Labour Party, which is the collective body of all the party’s MPs. It has a chairman elected by those Members of Parliament: from 1921 until 1970 the chairman of the PLP was also the leader of the party, but for the last half-century there has been a separate chair who acts as shop steward for Labour backbenchers. The post is currently held by the veteran left-wing MP for Leyton and Wanstead John Cryer; both his parents were Labour MPs, as is his wife, Ellie Reeves.

The Conservative Party, reflecting its traditions as a creation of the aristocracy and the gentry, is perhaps less rigorously democratic, but nevertheless has a body to represent its backbench MPs, the 1922 Committee. Two things may surprise you about “the ’22”, as it is known. The first is that it was not founded in 1922 (it evolved into being between 1923 and 1926). The second is that it is not really called the 1922 Committee, but is formally the Conservative Private Members’ Committee, a name which is slightly more accurate but not wholly correct.

To understand the ’22, we must go back to that year, 1922. Until that time there had been no real representation for backbenchers, nor had there really been much in the way of formal structures within the parliamentary party. There was not even an overall party leader at all. When in power, the Prime Minister was automatically regarded as filling that role, and was chosen, of course, by the sovereign, albeit on advice from leading parliamentarians. In opposition, there was a leader in each House, both regarded as formally co-eval, but neither post automatically entitled the holder to become premier after a general election victory.

When Lord Salisbury eventually stood down as Prime Minister in 1902, to be succeeded by his nephew A.J. Balfour (hence the origin of the phrase “Bob’s your uncle”), it was, little though anyone knew it at the time, the end of governments being led from the House of Lords. The upper chamber’s powers were significantly trimmed by the Parliament Act 1911, and thereafter it seemed unlikely that a peer would be invited to lead a government. When Andrew Bonar Law left Downing Street in 1923, terminally ill with throat cancer and unable to speak, the succession was felt to be between the hugely experienced and clever Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, and the middle-aged Worcestershire industrialist Stanley Baldwin, who had been Chancellor of the Exchequer for rather less than a year.

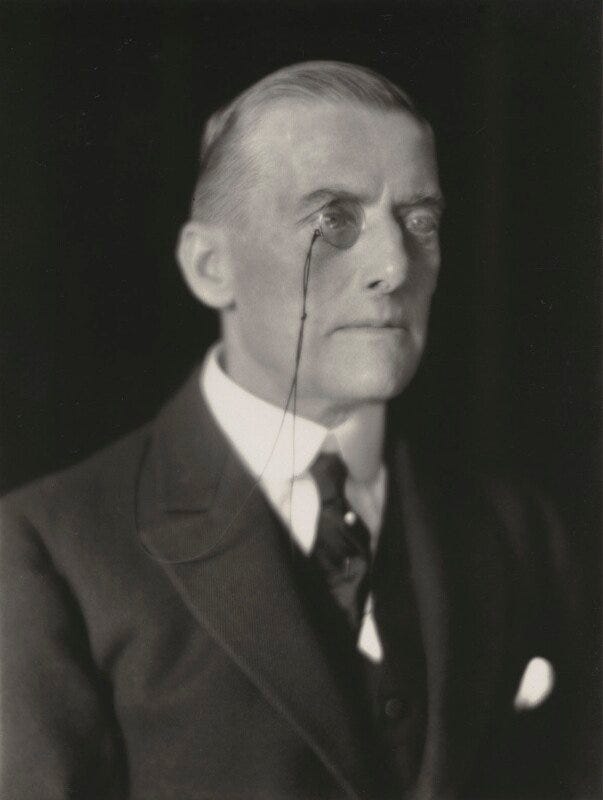

It should not have been much of a contest. Baldwin was a late starter in politics, having joined the Commons in his 40s, a wealthy iron and steel merchant who replaced his father as MP for Bewdley. He did not set the political heather on fire. It was 1917 before he was given any ministerial office, becoming Financial Secretary to the Treasury, and he only crept into the cabinet as President of the Board of Trade in 1921, by which time he was 53 years old. (He remains, curiously, the last graduate of the University of Cambridge to reach the premiership, a record which seems unlikely to be broken soon.)

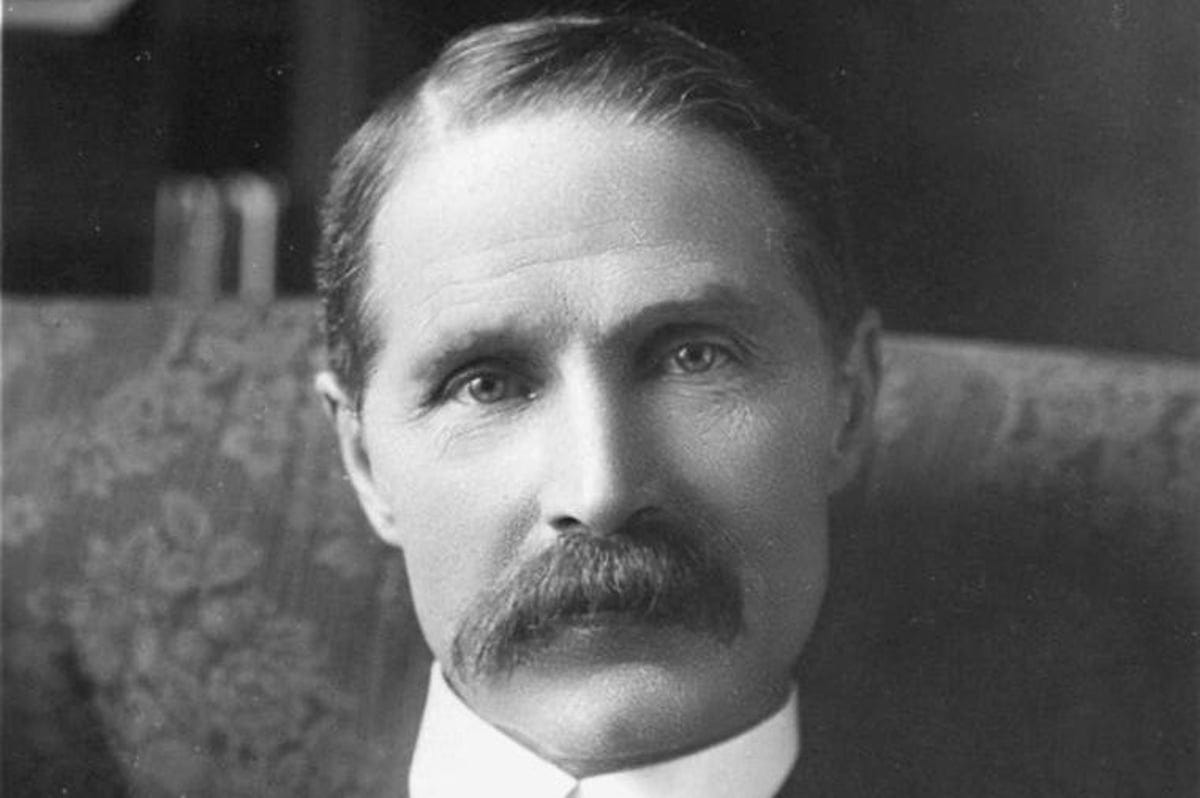

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, was a bird of a very different feather. From an ancient Norman family, he was educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford, that hothouse of Victorian statesmen, and was appointed Viceroy of India a few days before his 40th birthday. He was a formidable intellect, a Fellow of All Souls, Oxford, and a gifted speaker from his university days, though it was felt that he carried from the Oxford Union to the Commons and then to the Lords a decent measure of pomposity and arrogance as well as eloquence and wit. After his stint governing the 250 million subjects of British India, he had moved eventually and to no-one’s surprise into the cabinet in 1915 before becoming Foreign Secretary, a job he seemed both born and bred to hold, in 1919.

A generation earlier, the succession to Law would have been a foregone conclusion. The gifted and experienced Curzon would have been the obvious choice to lead the country and it would have been regarded as his birthright. By 1923, however, the main opposition party was the Labour Party, who had almost no representation in the House of Lords. That fact, added to the declining influence of the upper house, led to a feeling, particularly held by George V’s Private Secretary, Lord Stamfordham, that a peer could no longer reasonably be the head of government. As a result, the King summoned Baldwin, the ostensibly junior and less impressive candidate, to become Prime Minister.

We must dwell on history a little more: it is a vital influence all through out political culture, all the more so in the Conservative Party. Although the 1922 Committee was not formed in its titular date, 1922 was a formative year for the party and for the relationship of backbenchers to the government. By the autumn, David Lloyd George had led a coalition government for nearly six years. Although he was a Liberal, the government was dominated by Conservatives, who had won 379 seats at the 1918 general election (Lloyd George’s Coalition Liberals had 127 MPs while their former Liberal colleagues, led by H.H. Asquith, had slumped to 36). Conservative backbench MPs were growing weary of the brilliant, mercurial and venal Prime Minister: although Lloyd George was a master of politics, his judgement was deeply variable, and in September 1922 there was a war scare with Turkey over an obscure British garrison at the Anatolian town of Çanakkale.

The Welsh wizard maintained an almost hypnotic hold over his Conservative colleagues at the top of the government, like the Tory leader Austen Chamberlain, Leader of the House of Commons, the Lord Chancellor the Earl of Birkenhead, and the former Prime Minister and now Foreign Secretary the Earl of Balfour. But the spear carriers of conservatism, the backbench MPs, felt it was time for a change. Lloyd George might have been the right man to lead Britain through the First World War, but nearly four years later the mood was for a new Conservative prime minister and the jettisoning of the Coalition Liberals.

On 19 October 1922, Chamberlain called a meeting of Conservative MPs at the Carlton Club, then at 94 Pall Mall. (It was hit by a German bomb in 1940 and moved to its current home around the corner at 69 St James’s Street.) He hoped that his MPs would agree to continue the coalition government under Lloyd George, and there was to be a formal vote on how to proceed. This was a major innovation. For perhaps the first time, Conservative MPs were being given the chance to decide the future of the party. Here, understandably, the Conservative Party sees the wellspring of its own internal democracy.

The Carlton Club meeting did not go as the leadership hoped. Despite the imploring of Chamberlain and his senior colleagues, there were critical interventions in favour of leaving the coalition from Bonar Law, at that point a former leader, and Baldwin, the President of the Board of Trade. A senior backbencher, E.G. Pretyman, MP for Chelmsford, tabled a motion which declared:

That this meeting of Conservative members of the House of Commons declares its opinion that the Conservative Party, whilst willing to cooperate with Coalition Liberals, fights the election as an independent party, with its own leader and its own programme.

The 1920s were days of less rigorous record-keeping and openness, and we cannot be certain of the precise result. However, it is most commonly believed that, with 286 Members present, 187 voted in favour of the motion to leave the coalition and just 87 voted against. There are believed to have been around a dozen abstentions, and at least 11 MPs were absent.

This show of feeling by backbench MPs was decisive. Those ministers who had voted to come out of the coalition, like Baldwin and Sir Arthur Griffith-Boscawen, the Minister of Agriculture, resigned their offices. The pro-coalition grandees followed suit, and by the afternoon of 19 October, Lloyd George had gone to the Palace to resign as Prime Minister. By the beginning of the following week, Bonar Law had been re-elected unanimously as leader of the Conservative Party and was appointed Prime Minister later that day. Law’s cabinet was formed without many of the party’s leading figures, Chamberlain, Balfour, Birkenhead, Sir Robert Horne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the nominally Liberal Winston Churchill all standing aside. The new administration, lacking those senior figures, was dubbed “a government of the Second XI” by Churchill, while Birkenhead mordantly observed that the cabin boys had taken over the ship.

Law called an election almost immediately, and was returned with a solid majority. A few months into the new parliament, in April 1923, a small dining society of MPs elected the previous year. It quickly evolved into a sort of ginger group of backbenchers, designed to provide a platform for them to exercise some influence over the leadership. More newly elected MPs were added after the general elections of 1923 and 1924, and in 1926 it was named the Conservative Private Members’ Committee (though for shorthand known as the 1922 Committee) and opened to all backbenchers. The ’22 was finally born.

The extension of the 1922 Committee to all backbench Conservative MPs (ministers were formally admitted under pressure from David Cameron in 2010, though they cannot vote for its officers and executive) gave it the principal role it has today, which is to exist as a sounding board of backbench opinion and, in the person of its chairman in particular, a representative of the parliamentary party. This function was vitally important before 1965, when the party had no formal mechanism for electing or appointing its leader. The chairman would therefore be a key adviser on who would command the confidence of backbenchers in the event of a vacancy.

For backbenchers, the ’22 and the Conservative Party in general, 1965 was a critical year. Sir Alec Douglas-Home was at the helm, Leader of the Opposition since Harold Wilson’s general election victory the year before and previously Prime Minister. Home was not at all suited to opposition; although he had a dry, careful and surprisingly sharp wit, he was a man of government, ill at ease with the rough-and-tumble and day-by-day conflict of opposition. If he had been a somewhat reluctant premier, he certainly had never anticipated leading the opposition, and the party was in general agreement that he should be replaced (an outcome with which he was quite content).

Home’s accession to the premiership had been controversial. Harold Macmillan had resigned due to ill health on the eve of the 1963 party conference. Although choosing his replacement as prime minister was a matter for the Queen, she expected to receive advice as she had done in 1957, when Sir Anthony Eden had quit, and the fact that the party’s great and good had gathered in one place in Blackpool made the selection more public, chaotic and uncertain than anyone expected or wanted. Macmillan was confined to the King Edward VII’s Hospital in Marylebone, where on 10 October he underwent an operation on his prostate.

Macmillan’s initial preference as his successor, if ill-health was to curtail his term of office, was the Lord President of the Council, Viscount Hailsham, eligible in practical terms only because peers could by that time, under the terms of the Peerage Act 1963, disclaim their titles and then seek election to the House of Commons. Hailsham was a strange contradiction: a distinguished lawyer and a brilliant intellect who had won a first-class degree in classics at Oxford then a prize fellowship of All Souls, he was also an emotional, voluble and charismatic figure who had been a successful party chairman in the 1950s. Though some, including Randolph Churchill, were his fervent partisans, many in the party found him unpredictable and vulgar.

The nominal front-runner was Rab Butler, First Secretary of State and Deputy Prime Minister, who had been a fixture on the Conservative front bench since the mid-1930s. Butler had experience, cunning, intellect and ability: but some felt he lacked the killer instinct. He had been soundly beaten to the premiership by Macmillan in 1957, despite being in many ways senior, and many of the doubts which had denied him then still haunted him. In the absence of Macmillan, he delivered the leader’s speech at the party conference, and it flopped. It was not the key to his failure, but it was the final straw.

There was another set-piece speech given at every party conference, usually to little acclaim, that of the President of the National Conservative Convention, the body which represented the party’s volunteer win. By chance, the president for 1963 was the Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Home, who spoke well and was, it was soon noticed, also potentially able to give up his peerage to return to the House of Commons (where he had represented Lanark 1931-45 and 1950-51. The emergence of Home as a serious candidate would take many tens of pages to explain, but the idea emerged quickly, and, most importantly, came to be supported by Macmillan (allegedly because he had been advised that the US administration of John F. Kennedy was alarmed by a Hailsham premiership).

On 18 October, the Queen visited Macmillan in hospital. He presented her with a memorandum on the succession, which she forced him to read aloud: it essentially rehearsed the arguments in favour of Home becoming Prime Minister and recommended that the Queen send for him. She followed his advice later that day, and the following day Home returned to accept the invitation to form a government.

Some senior Conservatives felt that the Queen had been manipulated, that Butler had been cheated and that Home was not the best candidate. Two, Enoch Powell and Iain Macleod, felt so strongly that they refused to serve in Home’s cabinet (though both joined his shadow cabinet formed after the election the following year). Macleod quickly accepted the post of editor of The Spectator, and in January 1964 wrote a detailed and critical account of the leadership battle, dubbing it the result of a conspiracy of an Old Etonian “magic circle”. The name stuck, and it soon became received wisdom that the process was outdated and discredited. Humphry Berkeley, the moderate Conservative MP for Lancaster, was tasked with creating a set of rules for an open election, which were published in 1965. The voters in the election were to be Conservative MPs, and the 1922 Committee would oversee the process. In July 1965, Home resigned to trigger a contest, and Edward Heath was narrowly elected to succeed him.

By 1965, then, there was a clear election process administered by the ’22 to select leaders of the Conservative Party. There was, however, one peculiar lacuna in the rules: there was no mechanism for a challenge to a sitting leader. Perhaps Berkeley had felt that including a dagger within the mechanism of election would be a hostage to fortune; or perhaps he could not conceive of the circumstances under which a Conservative leader would lose the confidence of the party and yet attempt to remain doggedly in office. In any event, this gave a yet more prominent role to the Chairman of the 1922 Committee, as it was his responsibility to advise the leader honestly and frankly of the feelings of backbenchers.

This became an issue in 1974, when Edward Heath lost two general elections, in February and October, allowing the Labour Party to regain office. Heath’s position was not, prima facie, strong. He had lost three of the four elections he had contested, he had been Prime Minister for less than four years, he had made a significant economic U-turn in 1972 which was felt to have undermined his government, and he had little enthusiastic support among backbenchers. Heath was a chilly and standoffish man, difficult to talk to and brusque to an extreme. He had cut back on the honours usually distributed to backbenchers, which had caused offence, and his relations with even Tory-leaning press barons was poor.

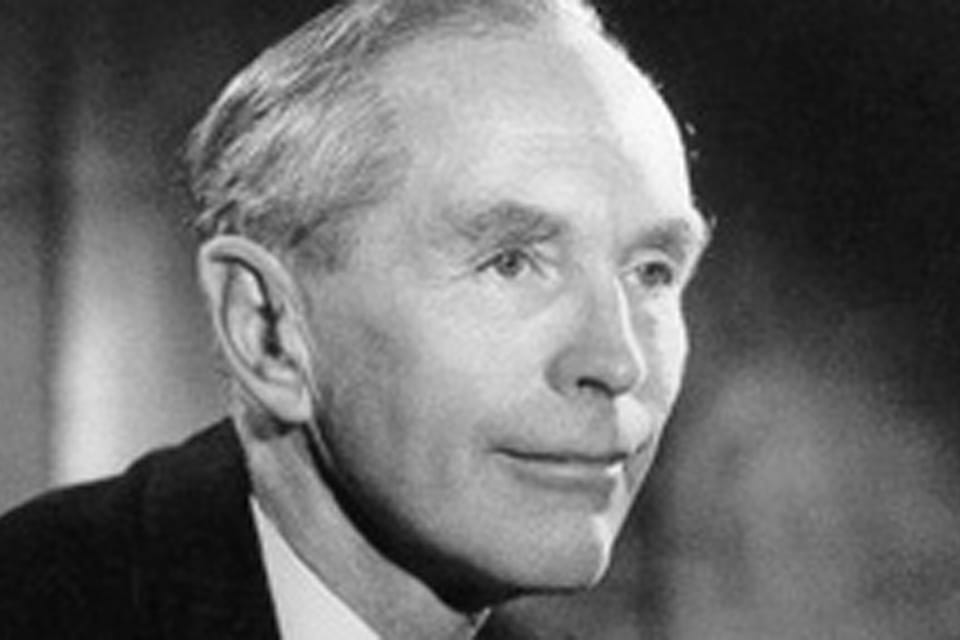

The Chairman of the 1922 Committee at this time was Edward du Cann, a 51-year-old financier who had been dropped as party chairman by Heath in 1967 and nursed a genteel grudge. Du Cann remains an enigmatic figure in Conservative annals. He was smooth and clubbable, prone to squeeze elbows and whisper in ears, but his adventurous business career as well as his personal manner made some old-fashioned Tories feel he was somehow non-U. Nevertheless, he seemed an obvious rival to Heath, much more obviously right-wing and with considerably more charisma. As Chairman, he summoned a meeting of the executive of the ’22 at his office in Milk Street which caught the attention of the press, and he looked like he was on manoeuvres, the attendees being dubbed “the Milk Street mafia”. As a leader he had qualities to recommend him, and was untainted by the failures of the Heath government.

Two things were happening. Du Cann’s 1922 Committee was believed to be lobbying Heath to consider his position, and Alec Home was revising the rules for leadership elections to create a provision to challenge an incumbent. Neither boded well for Heath. One ray of sunshine for the leader, however, was that Sir Keith Joseph, the former cabinet minister who had undergone an agonisingly public conversion to free-market economics and seemed to offer an alternative direction for the party, suddenly self-combusted. In October 1974, he gave a speech on poverty and the family. (Interestingly, the bulk of the speech was drafted by Jonathan Sumption, then a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, but from 2012 to 2018 a justice of the United Kingdom Supreme Court.) Typically of Joseph, it was a frank and heartfelt speech, but it was poorly phrased.

A high and rising proportion of children are being born to mothers least fitted to bring children into the world… Some are of low intelligence, most of low educational attainment. They are unlikely to be able to give children the stable emotional background, the consistent combination of love and firmness... They are producing problem children... The balance of our human stock, is threatened.

There was a whiff of eugenics about the speech, and the public reaction was poor. Joseph had never been a particularly suitable candidate for the leadership of the party. He was austere and convolutedly intellectual, and had no real sense of communicating with the general public.

With Joseph all but ruled out, du Cann was then scuppered. At the end of 1974, a government report on the activities of Keyser Ullman, the merchant bank of which du Cann had been chair since 1975, was heavily critical of the institution, and described du Cann as “incompetent” in his duties, allowing activities which were reckless and injudicious. It could have been designed to emphasise some of the doubts Conservatives had about the Chairman of the 1922 Committee, and he, too, was instantly no longer a plausible candidate.

Heath eventually submitted himself to a vote of the parliamentary party in February 1975. He expected—indeed, he felt he deserved—to be re-elected, demonstrating the poor judgement of his colleagues which would never leave him. Certainly, with Joseph and du Cann ruled out, and Enoch Powell having deserted the party to become an Ulster Unionist, there seemed no credible alternative, as the leading members of the shadow cabinet remained loyal while Heath was in office. He certainly had no inkling that his deputy Treasury spokesman, Margaret Thatcher, would unseat him. But that was exactly what happened. In the first ballot, she outpolled him 130 votes to 119, and while he eventually withdrew to allow loyalists Willie Whitelaw, James Prior and Sir Geoffrey Howe to enter the lists, the momentum was with Thatcher and she won comfortably.

Du Cann remained Chairman of the 1922 Committee until 1984. He was a soothing figure as the parliamentary party’s shop steward, and it is significant that the most prominent challenges to Thatcher in her early years came from within the cabinet rather than from backbenchers. By the time Cranley Onslow, a former spy and Foreign Office minister, was elected chairman in 1984, the Prime Minister was in her pomp. Onslow, however, exercised considerable influence. In 1986, he advised Thatcher that the Trade and Industry Secretary, Leon Brittan, should resign over the Westland affair (a scandal now remembered chiefly for Michael Heseltine’s dramatic walk-out from cabinet rather than the details of the titular helicopter manufacturer and the involvement of the government’s law officers).

By the end of the 1980s, however, Conservative backbenchers were restless again. Thatcher passed her 10th anniversary in office with seemingly no intention of retiring—she had said in a television interview in 1987 that she hoped “to go on and on, because I believe passionately in our policies.” This failed to reassure her supporters, especially as some of those policies like the Community Charge ran into huge popular opposition. Moreover she had no obvious successor: Cecil Parkinson, her first heir apparent, had fallen from grace in 1983, her long-serving Chancellor, Nigel Lawson, resigned in 1989, and that same year saw the dismissal of one of the shortest-lived and most improbably dauphins, John Moore, Social Services Secretary.

By this time there was an annual opportunity for the leader to be challenged. Every November there would be a confirmatory vote, and in 1989, a stalking horse emerged in the extraordinary and doomed figure of Sir Anthony Meyer, the 69-year-old MP for Clwyd North West. Meyer was an obscure baronet and passionate pro-European, from a rich family connected to the De Beers diamond concern, and he had spent some years as a diplomat. His profile outside Westminster was virtually nil, and he gained only 33 votes against Thatcher’s 314, but the full arithmetic revealed that 60 of the 374 Conservative MPs had failed to support the Prime Minister.

The following year, famously, saw Thatcher’s downfall. Her power was already waning, and she was already 65 years old; the determination of her earlier days had become imperious stubbornness, and discarded enemies on the backbenches were accumulating. Many factors came into play. Sir Geoffrey Howe’s famous resignation speech on 13 November 1990 was a breathtaking tour de force in mild-mannered savagery, and the following day Heseltine announced he would challenge Thatcher for the leadership. The Prime Minister’s campaign was little short of a disaster: she expected the fealty of her party (as, ironically, Heath had done 15 years before), and placed her future in the hands of her PPS, Peter Morrison, an ineffectual alcoholic and closeted homosexual who would later be accused of paedophilia. Morrison’s father had been Chairman of the 1922 Committee from 1955 to 1964, but the son had none of his feel for the party. At one point, Alan Clark, a dedicated Thatcher supporter, found Morrison asleep in his office.

When Thatcher failed to win the leadership on the first ballot, Onslow was among those who advised her to withdraw. He saw, as she, at that point could not, that even a technical win would be a catastrophic loss of authority. In another eerie echo of Heath’s downfall, Onslow insisted she needed to pull out so that her senior ministers could join the contest and prevent the victory of the insurgent Heseltine. Where Heath had failed, Thatcher was more successful. When she agreed to resign, John Major, her Chancellor, stood for election and won.

The 1922 Committee remains a hugely influential body in the fortunes of the Conservative Party, but in 1998 a considerable chunk of its power was given away. After the leadership election which had installed William Hague, a decision was taken to widen the franchise. Conservative MPs would no longer control the fate of the leadership, but would now simply narrow down the candidates to two, who would then be presented to the party’s membership at large for their choice. This has been a decisive change. In 2001, the MPs preferred Kenneth Clarke over Iain Duncan Smith by 59 votes to 54 (with Michael Portillo only one vote behind on 53), but the membership could not stomach the Europhile Clarke and elected the untested but ideologically pure Duncan Smith by 60% to 40%. It was, as we now know, a disastrous choice.

Those rules remain broadly in place. The leadership election of this summer saw Conservative MPs select Rishi Sunak as their favourite with 137 votes, and Liz Truss narrowly secured second place with 113 votes. Penny Mordaunt, who had been seen as a potential favourite among the membership, missed out on 105. The party members, as was widely suspected, did not warm to Sunak as a potential leader. The MPs’ favourite was beaten by Truss by 58% to 42%.

Perhaps the key role of the Chairman of the 1922 Committee now is as the recipient of letters of no confidence. The party rules state that an incumbent leader can be challenged if 15% of MPs submit letters which state they have no confidence in him or her. Critically, the Chairman is not required to reveal how many letters have been received or for whom, and need only notify the leader and the party when the 15% threshold has been met. As the current Prime Minister faces ongoing doubts in her leadership, the Chairman of the ’22, Sir Graham Brady, is once again in the spotlight.

Brady has been in post since 2010, longer than any other chairman. He stepped down for a few months in 2019, as Theresa May’s leadership crumbled and he considered a bid of his own. He is a popular man with his colleagues, and has managed backbench opinion carefully and deftly during a turbulent period. He was a Brexiteer, a sceptic of lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic and opposed the Northern Ireland backstop, giving him a solidly but not unsettlingly right-wing standing in the party. More than anything else, he is regarded as a fair and trustworthy umpire, which is vital for the working of the 1922 Committee.

This has been a much longer essay than I planned. Partly it is due to my inability to pass by a vaguely interesting anecdote, but I think the history of the ’22 and how it has performed in various leadership crises is a useful background for those watching the current political events. At the time of writing, only three Conservative MPs have openly called on the Prime Minister to resign: Reigate MP Crispin Blunt, serial critic Andrew Bridgen (who has now called for the resignation of every leader since David Cameron) and Jamie Wallis, the MP for Bridgend famous principally for walking away from a car crash and announcing that he is transsexual. More senior names have issued coded warnings, like Sir Malcolm Rifkind, former Chief Whip Andrew Mitchell and newly elected Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee Alicia Kearns. But we are not at the tipping point yet.

Only Sir Graham knows how many Conservative MPs have submitted letters of no confidence. It is in theory irrelevant, as a newly elected leader cannot be challenged under the current rules for a calendar year. However, that, like any of the rules, can be varied by the executive of the ’22. I will conclude by noting that that executive will meet today for the first time since Parliament returned from its conference recess.

Fascinating account of the 1922 Committee which must have taken some in-depth research. I love the history of politics (both here and in the USA) so look forward to further essays. Might not be long before the committee gets that 15% lack of confidence levy satistfied...let's wait and see.