The week in politics: observations in the margins

The news agenda has been dominated by riots in the UK and the presidential election in the US, but other stories continue to develop which are worth noting

Last week I wrote an essay rounding up some political stories which had not quite made the virtual front pages and about which I hadn’t written at length but wanted to flag up. This week, like last, has been dominated at home by the public disorder and internationally by the presidential election campaign, but politics is rather like Alan Bennett’s description of history, “Just one fucking thing after another”, and events do not, alas, form an orderly queue. So here are a few stories to be aware of, in case they passed you by.

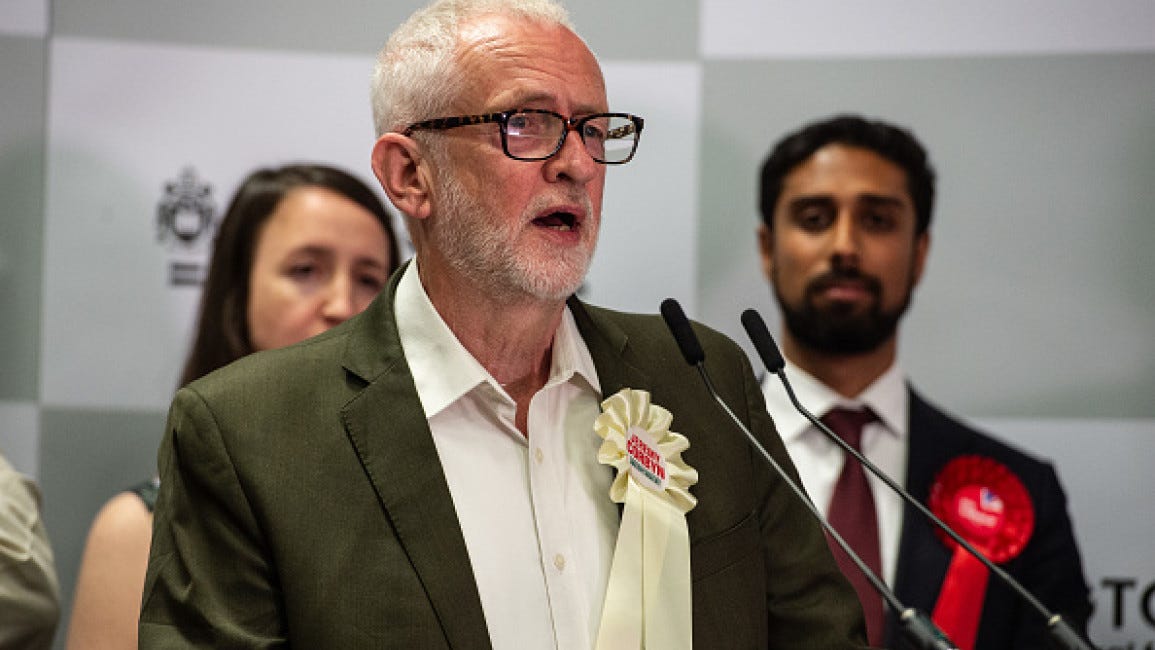

Oh Jeremy Corbyn

It is easy to overlook because of the Labour Party’s 174-seat majority, but the House of Commons now has six Members of Parliament elected as independents, an unprecedented number. The most high-profile, of course, is the former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn (Islington North), but he is joined by Shockat Adam (Leicester South), Adnan Hussain (Blackburn), Ayoub Khan (Birmingham Perry Barr), Iqbal Mohamed (Dewsbury and Batley) and Alex Easton (North Down). All are bona fide independent candidates with no hidden allegiances to mainstream parties, but Adam, Hussain, Khan and Mohamed campaigned principally on the plight of the Palestinian population of Gaza, while Corbyn is, of course, a veteran advocate of the Palestinian cause.

Easton is the outlier: formerly a Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) member of the Northern Ireland Assembly, he left the party in 2021 in exasperation, saying it had no “respect, discipline or decency”, and has then been an independent Unionist of a conservative and uncompromising stamp. He does, however, have a solid base of personal support in County Down (he was born and educated in Bangor and still lives and worships there). Although neither the DUP nor Traditional Unionist Voice put up candidates against him in July, which undoubtedly helped him to unseat the Alliance Party’s Stephen Farry by more than 7,000 votes, he has neither ties nor obligations to either party.

It is reported that the other five independent MPs are discussing the possibility of creating a formal alliance among themselves, given their common cause on Gaza. Their purported aim is to explore whether they can operate more effectively in Parliament as a co-ordinated group rather than as individuals, perhaps sharing resources and working tactically on scrutiny; they have already collaborated on amendments to the Humble Address following the King’s Speech last month. As a group of five MPs, they would be as large as Reform UK and the DUP, and larger than the Green Party, Plaid Cymru and the four smaller Northern Ireland parties, a fact of which they are fully aware.

However, unlike Reform UK et al, even if they established a formal umbrella group, they would not be eligible for additional public funds for their parliamentary duties, so-called “Short Money”1. The rules for Short Money are very clear. Funding is available to all opposition parties “that secured either two seats, or one seat and more than 150,000 votes, at the previous General Election”, and amounts to £22,295.86 for every seat won plus £44.53 for every 200 votes gained, as well as a share of a fund specifically for travel. The funding has a floor of £125,410 and a ceiling of £376,230.

But there is a catch, as far as the current independents are concerned. The terms of the relevant Resolutions of the House require that a qualifying party includes either “at least two Members of the House who are members of the party and who were elected at the previous General Election after contesting it as candidates for the party”, or “one such Member who was so elected and the aggregate of the votes cast in favour of all the party’s candidates at that election was at least 150,000”. The guidance issued by the Members Estimate Committee makes clear that these rules mean Short Money is not available to MPs elected without any party affiliation, whether or not they later adopt such an affiliation. One can take a view on whether this is fair, but it is the way the scheme currently works.

In truth, whether or not Corbyn and his potential allies qualify for some hundreds of thousands of pounds in public funding is a secondary issue. The government’s majority is not just large but crushing: it is in fact the third-largest House of Commons majority for a single party since the Great Reform Act, behind only the Conservative Party in 1924 (210) and the Labour Party in 1997 (179). In practice, a solid majority in the House of Commons puts the government in a very dominant position in parliamentary terms: the administration controls what business is considered anyway, and if it has the weight of numbers that Starmer enjoys, there is almost nothing any opposition parties can do to frustrate it.

The official opposition, with only 121 MPs, is facing a long and impotent parliament, so a potential grouping of five Members of Parliament would be barely a pinprick against the government’s thick hide. Even if the independents did form an alliance, they would not normally qualify for positions on select committees, and any advantage in terms of being called to ask questions would be almost imperceptibly marginal even if they were jostling with Reform UK and the DUP. (Indeed, I suggested recently in The Spectator that Nigel Farage, finally elected to Parliament on his eighth attempt, might be finding life as the leader of a minor party in the House of Commons disappointingly low-profile and frustrating.)

Whether or not they take the plunge or remain just friends, expect high-minded, frowning expressions of dismay from Corbyn, Adam, Hussain, Khan and Mohamed about the unfairly poor representation of minor parties in the procedures of the House, but the government has no motivation to make concessions, especially as all five independents beat Labour candidates into second place (and Adam unseated shadow cabinet member Jonathan Ashworth). If these pro-Palestinian independents have an influence on public policy, it will not come from within the House of Commons.

Peelers and planters: the Police Service of Northern Ireland

Although most of the media’s attention has focused on the recent riots across England, there has been related disorder in Northern Ireland: rioting began in Belfast on Saturday 3 August, alongside demonstrations in Bangor and Carrickfergus, and continued for several days. They have been partly caused by anti-immigration groups, but there is also evidence of involvement by the Ulster Defence Association, a Loyalist paramilitary group which was also engaged in the violent disorder in 2021.

Sadly, rioting in towns and cities in Northern Ireland is not unknown, albeit it is now more than 25 years since the Belfast Agreement and the establishment of a relatively peaceful security situation. What is surprising, however, is the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) has been forced to appeal to forces in Britain for assistance in order to maintain law and order. The Chief Constable, Jon Boutcher, has asked Police Scotland for 120 additional officers, arguing that his own exhausted men and women cannot “stand alone to deal with disorder like this any more”. He added that PSNI has been allowed to “decay” in recent years, leaving it unable to cope with sustained violence over many days.

The Northern Ireland Assembly was recalled on Thursday to debate the rioting. The Minister of Justice, Naomi Long, argued that PSNI was under greater pressure in terms of resources than at any time since 2010, that her department had received some of the smallest budget increases and that police numbers were at an historic low. This had had a serious effect on resilience and the ability to sustain operations. Last year, then Chief Constable Simon Byrne warned that the PSNI budget could become impossible to manage without significant additional investment, and optimism that Boutcher’s appointment to lead PSNI in November 2023 would bring stability and improvement has not been wholly justified.

The challenges facing PSNI are deep and extensive. It was created in November 2001 under the aegis of the Belfast Agreement to replace the Royal Ulster Constabulary, which was seen as a Protestant-dominated institution lacking cross-community legitimacy, but it has been plagued by a toxic combination of politicisation and professional failings. PSNI is overseen by the Northern Ireland Policing Board, a body made up on MLAs and independent lay members. Sinn Féin refused to participate in policing and justice until 2007, and the fact that one of their nominated members is Gerry Kelly MLA, who was convicted and imprisoned for involvement in terrorist bombings and shot a prison officer during an escape from HMP Maze in 1983, has been a source of tension with Unionists.

My friend Ian Acheson, an Ulsterman who has served as a prison governor, a special constable and a Home Office civil servant dealing with extremism, and therefore knows his public safety and security onions, proposed four causes for PSNI’s current plight. These were, in his words, “a. Failed NI Policing Board b. Failed senior leadership culture c. Tribal local politicians d. Ineffectual NIO/SoS”. There is certainly substance in all of these.

On leadership, Sir Matt Baggott (Chief Constable 2009-14) was criticised for responding hesitantly to major demonstrations and decided not to seek an extension of his term of office, while his successor, Sir George Hamilton (2014-19), was investigated for misconduct (though subsequently cleared) and refused a contract extension. Simon Byrne (2019-23) resigned last year after a major loss of data including personal details of officers by PSNI and a ruling by the High Court of Northern Ireland that two officers had been unlawfully disciplined to appease Sinn Féin. That is a worrying strike rate for an organisation of which Jon Boutcher is only the sixth chief constable.

As for the Northern Ireland Office, I wrote a couple of years ago in The Irish Times that for many Westminster politicians, the general perception of Northern Ireland has changed very little since Home Secretary Reginald Maudling’s remark on leaving after a visit in 1970, “For God’s sake, bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country.” In the main, ministerial appointments to Northern Ireland are either hardship postings or somewhere to put a politician for whom there is no other role. In recent years the only secretary of state who has shown any kind of enthusiasm and aptitude for the job has been Julian Smith (2019-20), widely respected and well regarded, and he was sacked by Boris Johnson after six months in post. Before him you have to go probably as far back as Peter Hain (2005-07) to find a secretary of state who fully grasped and relished the brief. Karen Bradley (2018-19) admitted that, on her appointment, she “didn’t understand things like… people who are nationalists don’t vote for unionist parties and vice-versa”.

If Ian’s critique is accurate, the problems facing PSNI are very deep-seated and will not be amenable to a quick fix. Perhaps Boutcher’s request for “mutual aid”, as police forces call it, from Police Scotland will shock the political community into realising how much needs to be done. As Ian noted wryly, “PSNI used to be net contributors—with much experience—to public order policing in GB. Now they are asking for help.” It will not be easy. It is encouraging that a new Northern Ireland Executive was formed in February, after two-year hiatus, and First Minister Michelle O’Neill and deputy First Minister Emma Little-Pengelly have been active in raising their and Northern Ireland’s profile. That they are still in post six months later is no small thing: the average length of a term since devolution is only 18 months, and O’Neill’s predecessor Paul Givan of the DUP only last eight months.

Addressing PSNI’s problems is part of a wider issue in Northern Ireland. For at least the last decade, governance has lurched from crisis to crisis, and there was no executive between 2017 and 2020 or between 2022 and 2024. Long-term planning and direction was utterly absent and any available political energy was devoted to crisis management. I have said again and again that O’Neill and Little-Pengelly must concentrate on establishing normality—essentially they must try to make Northern Ireland politics boring—and it is only through stable and sustainable government that the Executive will be able to plan for the future and attempt to undertake public sector reforms and achieve economic growth. But progress is only partial: a budget has been agreed for 2024/25, though the Minister of Finance, Dr Caoimhe Archibald, published it with the caveat that:

I will continue to make the case to the British Government that the Executive must be properly funded to put the Executive’s finances on a sustainable footing, that we need to be provided with a multi-year budget which enables long-term planning for service delivery.

A strategic Programme of Government has yet to emerge, despite repeated reassurances. Northern Ireland is still therefore living year by year and hoping for additional funding from the UK Government.

Parliamentary scrutiny meets social media edgelord

The role of social media in provoking and sustaining tensions since the beginning of the riots at the end of July has been much discussed. Peter Kyle, the Science, Innovation and Technology Secretary whose department is charged with “us[ing] technology for good by ensuring that new and existing technologies are safely developed and deployed across the UK”, sounded a note of exasperation with tech companies when he was interviewed by The Times last week.

It is unacceptable that social media has provided a platform for this hate. When I spoke to the companies I was very clear that they also have a responsibility not to peddle the harm of those who seek to damage and divide our society.

He indicated that he thought the provisions of the Online Safety Act 2023 might be inadequate. “It’s clearly a bit leaky at the moment”, he admitted. During parliamentary scrutiny of the legislation, the previous government bowed to complaints that proposals allowing Ofcom, the media regulator, to police “lawful but harmful” content on the internet were unnecessarily draconian and inimical to freedom of speech. As one campaigner said at the time, “Trying to make platforms do the job of law enforcement through technical means is a recipe for failure”. Kyle clearly remains unconvinced and argued:

When online activity is as significant as physical activity, we must make sure that it is policed with stridency and in the interests of safety first.

He is also unhappy at the combination of power and lack of accountability that he sees in the major tech companies. Of the “big five”—Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta and Microsoft—he noted:

Each of them spends more on R&D than Britain does. So we are dealing with companies that can innovate on a scale that the state can’t and none of them is accountable to general populations—they’re accountable to their customers and shareholders.

Kyle’s frustration may be understandable, but the apparent direction of his thinking should cause concern. He is quite right that the tech companies are “accountable to their customers and shareholders”, as private entities should and must be. They certainly are not accountable to “general populations”, except insofar as they are bound to observe the law in any jurisdiction in which they operate. There are laws governing harassment and incitement to hatred and violence, and these should of course be rigorously applied online as well as in the real world. But there is no justification for seeking to limit social media and instant messaging platforms if that threshold is not met, simply because the government does not like some of the things being said.

Elon Musk, the owner of X (formerly Twitter), has been particularly active in the arguments over the disorder and its supposed underlying causes. On 4 August, he commented on a video of rioting with the bleak and ominous phrase “Civil war in inevitable”; later that day he added “if incompatible cultures are brought together without assimilation, conflict is inevitable”. He has also attacked the Prime Minister directly, spreading the hashtag #TwoTierKeir to argue that ethnic minorities are subject to more sensitive and lighter-touch policing than white people and describing the police’s response to the disorder as “one-sided”.

The Government Chief Whip, Sir Alan Campbell, has written to Labour MPs advising them to exercise caution and restraint online. He is a wily old dog, first elected in 1997 and having spent 17 years in the Labour whips’ office, and he grasps that there is little advantage to come from wading into social media spats. His letter explained to MPs that it is “important that you do not do anything that risks amplifying misinformation on social media and do not get drawn into debates online”. Instead they should “amplify what is best about your local communities” at an “immensely difficult time” and help “restore order and calm”.

Campbell’s guidance is sound. It reflects the advice attributed to Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnar: “Don’t touch shit even with gloves on. The gloves get shitter, the shit doesn’t get any glovier.” Responding to provocative tweets by Elon Musk will neither deter the X Corp boss nor win over supporters.

Unfortunately some of Campbell’s colleagues are minded not to embrace his caution. Dawn Butler and Chi Onwurah are both seeking election as chair of the House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Committee when MPs vote on the posts in September, and both have seen the glitter of publicity. According to Politico, each is keen to question Elon Musk and other tech executives on the role and responsibility of social media platforms. Butler has said the committee should “question all owners of social media platforms”, and said of X “it’s a very powerful base, and we need to understand that power and make sure that it’s responsible”.

There is no doubt that hostile cross-examinations of high-profile witnesses, especially those reluctant to attend, can be parliamentary box office. When Rupert and James Murdoch appeared unwillingly in front of the Culture, Media and Sport Committee in 2011 to answer questions about tabloid journalists and phone hacking, the elder Murdoch struck a ghoulishly humble tone which made headlines, and then had a paper plate of shaving foam pushed in his face by a comedian to enhance the spectacle. There was more must-watch political drama in 2016 when retail billionaire Sir Philip Green was grilled for six hours by a joint meeting of the Work and Pensions Committee and the Business, Innovation and Skills Committee over his stewardship of collapsed high street fixture BHS. An angry and indignant witness clashed repeatedly with doggedly pious MPs, and it was impossible to look away.

There is a serious reputational risk for Parliament here, however. Select committees have the power to “send for persons, papers and records” (PPR), and if a potential witness refuses to attend under any circumstances, the committee can issue a formal summons requiring his or her presence. If this does not induce co-operation—and it was enough to persuade the Murdochs to comply—the committee can report the witness to the House for contempt. This is all great theatre and would be, prima facie, a telling display of Parliament bringing rich entrepreneurs to heel.

The problem is that no-one really knows what happens if a committee goes this far down the line. In theory, if someone is found in contempt of Parliament, he or she can be fined or even imprisoned; but no-one has been detained since 1880, and the last time a fine was imposed was in 1666. It is generally regarded as unlikely that powers which have been in abeyance for so long would withstand exposure to the contemporary legal system domestically and internationally, so the effect of raising the stakes could be to expose the fact that select committees are in fact powerless to require the attendance of someone sufficiently recalcitrant and brave.

Does it seem likely that Musk, a well practised provocateur and self-described “free speech absolutist”, would meekly submit to a parliamentary committee? Or is it more likely, given his stubborn, unpredictable and combative nature, not to mention a net worth of $222 billion, that he would seize every opportunity to defy, frustrate and expose the committee as a paper tiger, all in defence of freedom of speech?

Musk also lives primarily in Texas, so he is not even in Parliament’s jurisdiction to be served with a summons in the first place: this was a problem faced by the Business, Innovation and Skills Committee in 2010/11 when the Chairman and CEO of Kraft Foods, Irene Rosenfeld, refused to travel to the United Kingdom to answer questions about the company’s takeover of Cadbury’s. Angry MPs discussed the idea of a subpoena but it was not found to be workable.

The House of Commons Committee of Privileges published a report on select committees and contempts in April 2021 and laid out several options for reform. No action has yet been taken, however. The situation remains, therefore, that the exact limits of a committee’s powers are still not wholly tested nor clear, and that ambiguity can be a useful tool in negotiating with reluctant witnesses. I have had to engage in these kinds of delicate exchanges more than once—one chairman waved me away with a cheery “The future of the select committee system is in your hands!”—but the balance of probability is that to test PPR powers to their ultimate limit would result in a defeat for Parliament. Musk is arguably the wrong opponent and this is certainly the wrong ground on which a committee should fight him. Perhaps Butler and Onwurah will reflect over the summer adjournment and seek alternative methods of scrutiny.

È finita la commedia

I hope this has been useful in highlighting briefly some of the stories which were elbowed aside by the headlines over the past week. I have a feeling some or all of them may return.

It is known as “Short Money” because the system was introduced in 1975 by the Leader of the House of Commons, Edward Short, later Lord Glenamara.

Or the aphorism oft attributed to George Bernard Shaw: "Never wrestle with a pig. You both get filthy and the pig enjoys it."

"As a group of five MPs, they would be as large as Reform UK and the DUP, and larger than the Green Party, Plaid Cymru and the four smaller Northern Ireland Unionist parties, a fact of which they are fully aware."

I think you mean "two smaller Northern Ireland Unionist parties" i.e. the UUP and TUV or "four smaller Northern Ireland parties" i.e. SDLP, Alliance, UUP and TUV.