"The Good Nazi", Speer and Nuremberg

It's easy to be critical of the Nuremberg trials and their legacy, but it was an extraordinary process which had some unexpected consequences

I wasn’t sure how to begin this, as there were several neural sparks which made their contribution, an unusually broad and cattywampus agglomeration of thoughts, stimuli and instincts, so I’ll start with Monday afternoon, as good a place as any to start. I was deliberately not doing anything for a few minutes: I don’t claim that the result is better or swifter, but my brain whirrs at a rate which can be a little wearying, leaping from one thing to another and scribbling mad, frantic to-do lists which I know will never be realised in full. For no reason I can explain, I started thinking about the concept of six degrees of separation, what some call the “six-handshake rule”. This is the notion that everyone in the world is at most half a dozen social connections apart, and that we can make some extraordinary leaps from our own ordinary lives.

The idea started to be kicked around in the 1920s, at a time when academics were fascinated by flows and connections and networks, but it was really fixed in the popular imagination by a play of 1990, Six Degrees of Separation by John Guare; three years later, it was transformed into a creditable film for which Stockard Channing won an Oscar nomination (and which was one of Will Smith’s first big-screen outings). As a theory, of course, it is nonsense, rather more plausible to the legions of poundshop Nathan Barleys one still finds in the wrong parts of London than to a Bedu on the fringes of the Empty Quarter or a novice in one of the 20 monasteries clinging to Mount Athos.

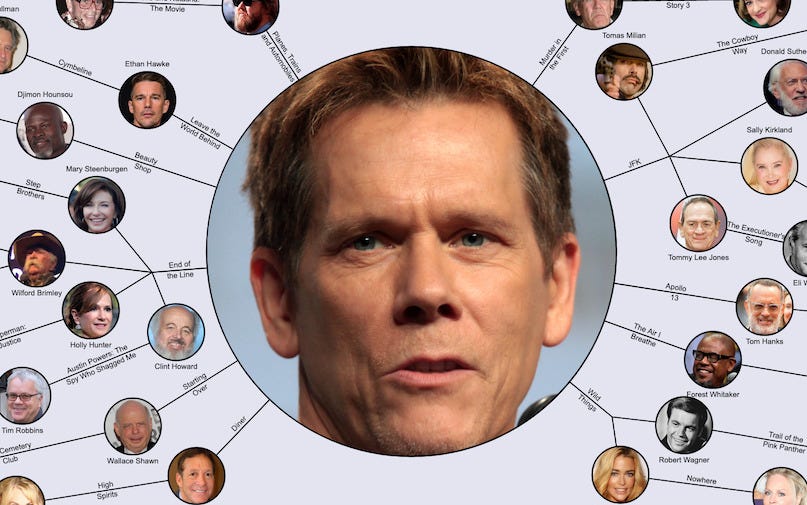

When I was a teenager, the theory was refined into a parlour game—do we still talk about ‘parlour games’? Do people even know or care what parlours are?—focused on the prodigious output of one actor, “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon”. Its creators, three liberal arts students (what else?) from Albright College in Pennsylvania, wrote to the comedian Jon Stewart, then hosting a late-night talk show on MTV, and the idea caught on to such an extent that it inevitably became a book with a foreword by, of course, Kevin Bacon. And I was on Monday loosely playing a game of that in my head, I suppose, albeit a non-thespian one, when I realised that I could connect myself, with one link to spare, with Adolf Hitler.

Let me try to explain. That afternoon, on one of my regular prostrations before the altar of YouTube, I had watched an interview from 1995 in which veteran interviewer Charlie Rose quizzed journalist and biographer Gitta Sereny. The Austrian writer was appearing on Rose’s show to promote her then-new book, Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth, which, although not perfect, is a scintillating portrayal of a senior member of the Nazi régime. But she would go on to write a very different biography three years later, Cries Unheard, the story of Mary Bell. Often forgotten now, Mary Bell had, as a 10- and 11-year-old girl in Scotswood, a brutally deindustrialising area of Newcastle, killed two young children, Martin Brown (4) and Brian Howe (3). The whole case is of course tragic but absolutely fascinating, not least because of the incredible and seemingly instinctive humanity with which the justice system dealt with everyone involved.

But I digress. My point was six degrees of separation, and this hinged, weirdly, on Sereny. She had, of course, spent many hours with Albert Speer, Hitler’s armaments minister and favoured architect. But she had also met and spent time with Mary Bell, who is 66 now and lives, somewhere, in court-protected anonymity under a pseudonym. And early on in her career dealing with disruptive children and young people, my mother had met Bell (though I’m afraid I don’t know the details and missed the opportunity to ask). So there we have this improbable link, which runs from your humble correspondent, to Jo Wilson, to Mary Bell, to Gitta Sereny, to Albert Speer, to Adolf Hitler.

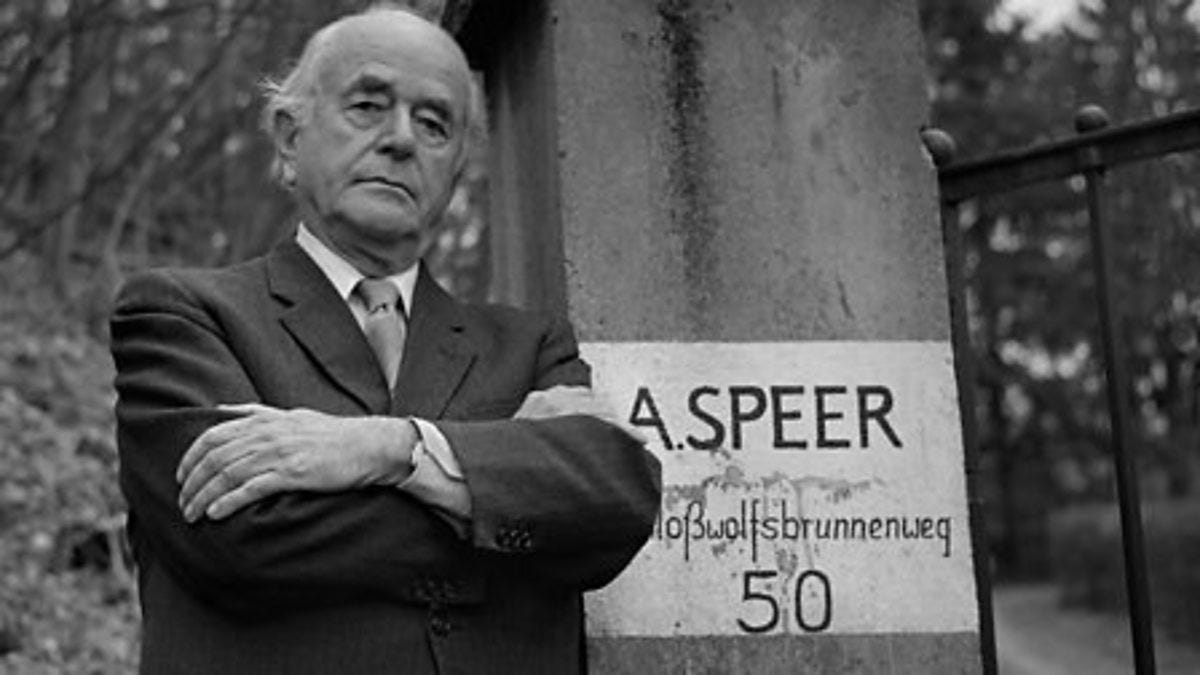

All of this led me to think more about Albert Speer. As it happens, our lives overlapped briefly: I was approaching my fourth birthday when he died after a stroke at the age of 76. (Another weird coincidence if you care about these things: he died in St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, where I go regularly to see my consultant. It really is a small world.) Speer has always fascinated me because of the unique narrative he created around himself: much of the so-called “Speer legend” has been dismantled and exposed by historians, and its most self-exculpatory elements were vile hogwash by a self-serving man with a damaged psyche. Sereny herself was criticised by some for becoming too close to Speer and losing critical detachment, but her biography concluded that much of his mythology was untrue and that he had known, contrary to his claims, about the Endlösung der Judenfrage, the Final Solution to the Jewish Question, which was formalised and systematised at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942. (Maybe it’s my professional immersion in bureaucracy but one of then most chilling aspects of Wannsee for me is that the “conference” took 90 minutes, after which the delegates had lunch. An hour and a half, to settle the fate of European Jewry.)

But Speer’s mythology was not as simple as total denial of culpability or knowledge for what the Nazis régime had done. He was too intelligent to think that was remotely plausible. At Nuremberg, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison for warm crimes and crimes against humanity; although three of the eight judges wanted the death penalty, they compromised on a long custodial sentence which Speer served in full, as Prisoner Number Five in Spandau Prison. Three of his fellow inmates were released early, while one, Rudolf Hess, once Hitler’s deputy, died, supposedly by suicide, at the age of 93. So Speer could legitimately say that he had accepted punishment, strict punishment, even, for his part in the collective guilt of his nation. But he tried to portray that responsibility as generalised, even theoretical. In his 1970 confession, Inside the Third Reich, Speer put his position like this: “I didn’t know, I could’ve known, I should’ve known but I did not.”

It was an attractive line for a Germany drained by 25 years of unbearable guilt and painted, despite its great achievements in art, culture, music and literature, as a semi-bestial tribe darker still and more frightening than anything Varus had encountered in the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9. It offered an admission of guilt, of course, because who could escape that, but it suggested that, after all, not every German had been a camp guard nor every German a rabid anti-Semite. They had been difficult times, one was to infer, and if those who were just trying to get by and stay safe made decisions that in hindsight looked like poor judgement, well, that was human nature.

I want to go back for a moment to the Nuremberg Trials themselves. That the defeated German leadership was subjected to any kind of formal judicial process was by no means certain. There was, after all, no precedent for such a systematic approach to a vanquished enemy: during the First World War, the Allies had developed the novel theory that individual leaders should be held criminally responsible for violations of international law, and articles 227 to 230 of the Treaty of Versailles made provisions for creating special international tribunals to try senior individuals from the Central Powers starting with Kaiser Wilhelm II. But the process foundered on a multiplicity of technicalities, and in May 1920 it was agreed that a much slimmer list of 45 individuals be indicted and tried by the German Reichsgericht in Leipzig. In the end, only 12 of those named appeared in court, and the process fizzled out.

The peculiar enormity of the Holocaust changed many people’s thinking in the Second World War. The conflict could not just be written off as another set of state-on-state rivalries, and there must be recognition that a line had been irredeemably crossed. In 1942, representatives of nine governments-in-exile in London—Poland, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Free France, Greece, Yugoslavia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Norway—published a resolution (additionally supported by Chiang Kai-Shek’s Republic of China) which called for legal proceedings against the Axis leaders. The US and UK governments were initially sceptical, aware of the dismal failure of the process after Versailles; while a United Nations Commission for the Investigation of War Crimes was established in October 1943 at the instigation of the British government, particularly the Lord Chancellor, Viscount Simon, it did not include Soviet representatives and succumbed to internal jurisdictional and legal arguments. At the end of the month, however, the four Allied powers—the US, the UK, the USSR and the Republic of China—agreed the Moscow Declarations, which reiterated their demand for unconditional surrender; its fourth article underlined the idea that there would be a reckoning for German (and other) atrocities.

The fourth article was largely the penmanship of Winston Churchill, and it shows This was no cold, flat, diplomatic prose, but an indictment of evil which blazed forth from the page with the chorus of a million murdered souls behind it. The Allied powers:

Hereby solemnly declare and give full warning of their declaration as follows… those German officers and men and members of the Nazi party who have been responsible for or have taken a consenting part in the above atrocities, massacres and executions will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done in order that they may be judged and punished according to the laws of these liberated countries… [they] will know they will be brought back to the scene of their crimes and judged on the spot by the peoples whom they have outraged. Let those who have hitherto not imbued their hands with innocent blood beware lest they join the ranks of the guilty, for most assuredly the three Allied powers will pursue them to the uttermost ends of the earth and will deliver them to their accusors in order that justice may be done.

This was Old Testament stuff. But these were principles, not codes of practice or implementation. The mechanisms for delivering this justice were still to be agreed, and consensus had not been reached when the Allied leaders met at Yalta in February 1945.

President Franklin Roosevelt was all but a dead man: he was suffering from high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease causing angina pectoris, and congestive heart failure and would die two months after the conference. He was already suffering from recurrent minor seizures which could leave him dazed and unable to communicate or think for seconds or minutes at a time, and there have been some suggestions that he was suffering from a brain tumour (though his body was never subject to a post-mortem examination, so we shall never know). On the issue of justice, he and his officials still took by far the most high-minded approach. There must be an open and fair trial, which would demonstrate not only the superiority of the western liberal democratic order but would be seen as a legitimisation of efforts to reform post-war Germany. The Department of War, under the septuagenarian Henry Stimson, had been preparing for a tribunal since late 1944; Stimson was a Harvard Law School graduate, a partner at Wall Street grandees Root and Clark from 1893 and a US attorney with a strong anti-trust record under the first President Roosevelt.

Perhaps surprisingly, Stalin too was keen for there to be a trial. But his conception was of a 1930s-style show trial, the outcome predetermined, the purpose of the trial being to demonstrate the guilt of leading members of the Nazi régime and strengthen the case for Germany to pay reparations to help repair the Soviet economy. They also led the way on the charge of waging a war of aggression, a principle developed by Soviet jurist Aron Trainin, a brilliant Jewish lawyer from Vitebsk in the Pale of Settlement (now Viciebsk in Belarus). Trainin argued that the systematic and unrestrained nature of the Nazi war machine meant that its crimes had to be reframed in a way which took account of this, hence his creation of a crime against peace. Such a conception was, to say the least, bold by a servant of a régime which had invaded and occupied eastern Poland once the German armed forces had torn the guts out of the Polish defenders; annexed parts of Karelia and Salla from Finland in March 1940; and absorbed the Baltic States and parts of Romania in summer 1940. But what Trainin’s reframing did was to position the Soviet Union as a “peaceful” victim of German aggression.

The UK government still held to a more straightforward solution. Churchill (rightly) feared the prospect of a Soviet-style show trial, and British officials were anxious about the precedent which a prosecution for waging aggressive war might set. The prime minister’s preferred plan was the summary execution of leading Nazis and the imprisonment without trial of others. It was not a simple spree which Churchill proposed. According to diary of Guy Liddell, director of MI5’s B Division (counter-espionage), the recently appointed director of public prosecutions, Theobald Mathew MC, had recommended:

That a fact-finding committee should come to the conclusion that certain people should be bumped off and that others should receive varying terms of imprisonment, that this should be put to the House of Commons and that the authority should be given to any military body finding these individuals in their area to arrest them and inflict whatever punishment had been decided on.

It’s hard to credit today, but Liddell concluded “This was a much clearer proposition and would not bring the law into disrepute”. The involvement of the House of Commons is interesting (from my point of view). Handwritten notes by the deputy cabinet secretary, Norman Brook, distinct from the official minutes of the War Cabinet, show that Churchill believed Hitler should be treated as an outlaw if captured, and would, along with other senior Nazis, be summarily executed. But there was an awareness that this might be legally precarious: this was to be resolved by bills of attainder against those condemned to execution.

A bill of attainder is a piece of draft legislation which essentially declares the guilt of an individual, the parliamentary process standing in for a conventional trial. It was first used in 1321 on Hugh le Despenser and his son Hugh the Younger, who were attainted and sent into exile for supporting Edward II against Queen Isabella and her supporters, and was most recently employed in 1798 against Lord Edward Fitzgerald, leader of the rebellion of the Society of United Irishmen. But the remedy remained (and remains) available, and its degree of desuetude clearly did not concern Churchill. It would, however, have been an extraordinarily advanced and adventurous piece of jurisprudence, to use a mediaeval English statutory procedure to punish non-British subjects for alleged crimes largely committed outside the jurisdiction of UK law.

Adolf Hitler committed suicide in Berlin on 30 April 1945. His role as Führer went into abeyance on his death; in line with his expressed wishes, the commander-in-chief of the Navy, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, became President of the Reich and head of state, while the propaganda minister, Dr Joseph Goebbels, was named chancellor. Dönitz was based in Schleswig-Holstein, in relative safety, while Goebbels had dedicated himself to the defence of Berlin. The latter’s term of office was staggeringly short; in his only official act as chancellor, he dictated a letter to the Soviet commander in central Berlin, General Vasily Chuikov, informing him of Hitler’s death and requesting an armistice, but this was refused. That evening, he and his wife Magda murdered their six children then committed suicide. Dönitz named as “Leading Minister” (Leitendem Reichsminister) the long-standing finance minister, Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, a conservative Lutheran aristocrat who had been a Rhodes Scholar at Oriel College, Oxford, from 1905. But the régime was collapsing, and Germany surrendered unconditionally on 8 May.

The newly sworn-in President Harry Truman had finally announced in 2 May that there would be an international tribunal to try senior Nazis. The details were gradually worked out at the London Conference from June to August 1945, which agreed the Charter of the International Military Tribunal, whereby individuals could be charged with crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity, and it excluded the defence of sovereign immunity. In hybrid of civil and common law, it featured a panel of judges, two from each of the four Allied powers, the second of whom was a deputy without voting rights.

The US judges were Francis Biddle, former US attorney general, and John Parker, form the US Court of Appeal for the Fourth Circuit; the UK nominated Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, a lord justice of appeal who became the titular president of the judicial group, and Sir Norman Birkett, a high court judge in the King’s Bench Division; France appointed Henri Donnedieu de Vabres, a professor of criminal law from the Sorbonne, and Robert Falco, who had been dismissed as a judge on the Court of Appeal of Paris because of his Jewish origins; while the Russian nominees were Major-General Iona Nikitchenko, from the USSR’s supreme court, and Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Fyodorovich Volchkov, whose previous careers included diplomacy and the Soviet film industry.

The International Military Tribunal opened on 20 November 1945. Twenty-four defendants were indicted, of whom three did not appear in the witness box. Martin Bormann, who held many offices but whose power rested on that of Hitler’s private secretary, was charged in absentia, although he was probably already dead, his body buried near the Lehrter Bahnhof in central Berlin and eventually identified in 1973. (There were, and still are, dozens of conspiracy theories involving Bormann escaping to Argentina, Paraguay, Spain, Chile, Ecuador, Florida and other exotic locations; he didn’t. He died, probably shot by Soviet soldiers, on the train tracks by the station, probably on 2 May.) Also technically under indictment was the industrialist Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, chairman of Friedrich Krupp AG, but he was bedridden and senile by the time of the trial and was not actively prosecuted. The third to escape the stand was Robert Ley, the arrogant, Jew-baiting drunk who headed the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, the Nazi labour organisation; he was captured by US paratroopers on 15 May but strangled himself, fittingly, from a toilet pipe on 24 October.

With Hitler, Himmler and Goebbels having committed suicide, the remaining 21 defendants were intended to represent the political, military and economic leadership of Nazi Germany. In alphabetical order they were as follows:

Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, President of the Reich

Hans Frank, Governor-General of the General Government

Wilhelm Frick, Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia

Hans Fritzsche, Head of Radio, Ministry of Propaganda

Walther Funk, President of the Reichsbank

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, former C-in-C of the Luftwaffe

Rudolf Hess, former Deputy Führer

Colonel-General Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations, Armed Forces High Command

Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Director of the Reich Main Security Office

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the Armed Forces High Command

Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath, former foreign minister

Franz von Papen, former chancellor and vice-chancellor

Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, former C-in-C of the Navy

Joachim von Ribbentrop, foreign minister

Alfred Rosenberg, minister for the Eastern Occupied Territories

Fritz Sauckel, General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment

Hjalmar Schacht, former President of the Reichsbank

Baldur von Schirach, Gauleiter of Vienna

Artur Seyss-Inquart, Reichkommissar of the Netherlands

Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments

Julius Streicher, publisher of Der Stürmer

(It is a nicely ironic fact that Kaltenbrunner, head of the various police forces of the Nazi state, was also at that time President of Interpol.)

However many counts the defendants were facing, when they were formally indicted in Courtroom 600 of the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, universally they entered the same plea: “Nicht schuldig”, not guilty. The case against them was conducted by the prosectors from the four Allied powers, starting on 21 November 1945 and concluding with the last Soviet contribution on 6 March 1946. Here is not the place for the tale of the trial, which is gripping, moving and hugely important, but it is worth noting that it was not a show trial. Each of the defendants had legal representation and many resisted the charges fiercely. In truth, though, the comprehensive case by the Allied prosecutors meant that it was simply a matter of allotting guilt. But observers were shocked when three defendants were acquitted at the end of the process: Papen, the dim-witted aristocrat who had encouraged President Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as chancellor in January 1933 with the undertaking that he, as vice-chancellor, would be able to control the Nazis; Schacht, the brilliant economist who had become more and more disillusioned with Hitler’s régime until he was arrested in the wake of the July Plot against the Führer and spent the last months of the war in concentration camps; and Fritzsche, an unpleasant dimwit but essentially a radio presenter whom many felt had been indicted essentially as a proxy for Joseph Goebbels.

Speer’s approach to the trial was singular. He had chosen as his lawyer Dr Hans Flächsner, a mild-mannered, approachable man in his late 40s, and told him that he intended to take responsibility for the crimes of the régime. Between them, though, they charted a delicate course by which Speer would accept a kind of generalised responsibility while denying specific knowledge of the worst excesses of Nazism. Although he could not evade responsibility for the extensive use of slave labour and forced labour in the armaments industry, he calculated rightly that the prosecution could not prove that he had known about the wider Holocaust.

His closing remarks, given on 31 August 1946, are fascinating to watch, especially as we now know how elaborate a performance it was. Playing to what was by any estimation a tough crowd, he handled the occasional with supreme delicacy: Hitler had ultimately been to blame, of course, and had perpetrated a terrible crime on the civilised German people as well as on all of their victims, but sacrifices had to be made and he, Speer, took little account of his own fate in the wider sweep of justice. Almost daring the judges to condemn him, he was sombre, serious but with the hint of detachment which resignation brings, as if he had completed his important mission of explanatory exculpation, and now had no great anxiety for what lay ahead.

There were many people who felt that the Nuremberg process was deeply, perhaps fatally flawed. Even while the trial was in progress, Charles E. Wyzanski Jr, a Boston lawyer and judge on the US District Court for Massachusetts, wrote at length in The Atlantic questioning the legal basis for the tribunal and the charges which it had laid against the defendants. A year later, in 1947, future giant of constitutional law, Herbert Wechsler, who had worked for the US judges at Nuremberg, summed up many of the criticisms in the Political Science Quarterly, not least the notion of creating crimes after they had been “committed” and the potential threats paused to US law by these new international principles.

These critiques should not be dismissed. The International Military Tribunal was imperfect, and demanded that much was ignored (such as the Soviet participation in invading Poland in 1939) and much accepted on trust, such as the authority of the Allied powers to initiate a prosecution against a fellow sovereign country. Nuremberg was, to an extent, “victors’ justice”, but what an extraordinary legal, intellectual and moral framework it created, a first draft of how the world would try to keep available a sense that governments were responsible for their actions on the international stage. The British plan, to winnow out the worst offenders of the régime and execute them summarily, would not have been an impossible marketing job on a continent hollowed out by war. There would also have been few hairs turned at the same result achieved after going through the motions of a judicial hearing, a show trial as the Soviets had wanted.

Yet there is a strong sense that, while some of the indictments were foregone conclusions, the judges really did consider each case with a relatively open mind. As mentioned above, three defendants were acquitted entirely, Fritzsche, Schacht and von Papen; others had received prison sentences ranging from 10 years, like Grand Admiral Dönitz, to life imprisonment. Equally, the drama was continually alive with 11 death sentences (plus Bormann’s sentence in absentia), two recipients of which, Robert Ley and Hermann Göring, cheated the hangman by committing suicide.

But this was a full spread of possible outcomes. The Allies could at least superficially proclaim that they had handled the cases diligently and with skill, and that the defendants had been able to mount defences which had at least given them proper representation. The Luftwaffe chief, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, had been yhe most extraordinary example of this; one of the more charming and less personally abhorrent of the senior Nazis, he had collected positions and titles since 1933 and had been regarded as Hitler’s natural successor. But when his promises to keep the 6th Army at Stalingrad supplied by air had proved illusory, and the remaining 91,000 German soldiers had surrendered in February 1943, Göring’s star had begun to wane. He was invited to fewer conferences, spent more time at his country estates, ate gluttonously and developed a chronic morphine addiction, at its height between 260 mg and 320 mg per day: that’s the sort of dosage we give today to palliative care patients.

When Göring was taken into US custody on 6 May 1945, however, he was put in temporary accommodation where he was weaned off his drug addiction and underwent dramatic weight loss (one of the most striking features of his appearance at the trial is big his uniform was). He suddenly crackled into life and was sharp-witted, argumentative and outspoken (his IQ was tested and found to be 138, an exceptionally high rating notwithstanding the limitations of IQ tests). When he was indicted, he sparred with the prosecutors, making no apologies for the operation of the Nazi state and rejecting the standing of the court to try him. It was, of course, in vain—more than anyone else present, Göring’s conviction was inevitable—but it was truly bravura performance. (This short clip shows how calm and in control Göring seemed, and how engaged he was with the arguments.)

If Albert Speer stood out, however, it was not just because of his decision to accept responsibility for the atrocities of Nazism. In truth, most of the other defendants were firmly mediocre. Rudolf Hess, one-time deputy führer, who had flown to Scotland in 1941 in an unlicensed attempt to broker a peace settlement between Germany and the Allies only a few weeks before Hitler had launched his invasion of the Soviet Union, had spent the rest of the war in custody, attempting suicide twice and claiming (falsely, it would transpire) to be suffering from amnesia. Although he was assessed medically fit to stand trial, he was clearly in some kind of mental distress, withdrawing deep into himself and able to shut out reality for long periods. Various doctors had assessed him during his captivity as suffering from “paranoid psychosis”, having a “psychopathic personality of the schizophrenic type” and suffering “a severe psychoneurosis of the hysterical type”. Later diagnoses attributed to him “a psychogenic paranoid reaction”, “a marked hysterical tendency” and “a psychopathic personality”. Whatever was wrong with Hess—the doctors were more or less playing psychiatry bingo in the inability to agree on a diagnosis—it rendered him essentially a null at the trial. One wonders if modern judicial medicine would even have allowed him to stand.

After a dozen years of the Thousand-Year Reich, its remaining leaders were dismal. Wilhelm Keitel, head of the Armed Forces High Command (OKW), was dismissed by Göring as having “a sergeant’s mind inside a field marshal’s body”, mocked by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt as possessing “the brains of a cinema usher”, and had reached his eminence by his ability to agree enthusiastically with Hitler; he had probably reached his natural level as a junior artillery officer in the First World War. Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Reich Main Security Office, was a mediocre Austrian lawyer, vastly tall, whose chief qualities were virulent anti-Semitism, slavish devotion to Hitler and a nasty tendency to bully downwards. The role of war criminal ha found him rather than vice-versa but he had shown at least dogged enthusiasm for it.

Joachim von Ribbentrop had been foreign minister from 1938 to 1945, and before that German ambassador to London. In his early 30s, he had been adopted by his aunt so that he could take on her nobiliary particle, “von”; this, plus his employment as a champagne salesman, had given him what to Hitler seemed a veneer of glamour and sophistication when they had met in 1928. Although at school he had been described by one of his teachers as “the most stupid in his class, full of vanity and very pushy”, he spoke fluent English and French, and his smoothness made some party veterans resent him. He became an adviser on foreign policy to Hitler, but this was based largely on his having travelled more extensively than most senior Nazis, and his firm convictions amounted to a dislike on Communism and a mild yearning for the monarchy to be restored. Ribbentrop had one uncanny skill, however; he could absorb the main points of what Hitler said, digest them and project them back at the Führer, to his delight. In Wechsler-Bellevue terms, he was found to score highly, but he was an intellectual and moral blank.

There were men like Baldur von Schirach, a vaguely aristocratic youth leader, not yet 40, who pleaded at the tribunal that he renounced Nazism; a measure of his intellectual flimsiness was his conversion to anti-Semitism after reading Henry Ford’s four volumes of junk bile, The International Jew. Artur Seyss-Inquart, an ethnic German from Moravia, had been chancellor of Austria for all of two days before the Anschluss in 1938; thereafter he had roamed Nazi-occupied Europe lending an oppressive and authoritarian hand in Southern Poland, the General Government and the Netherlands. Alfred Rosenberg, born in Tallinn to mixed heritage of which very little was German, had become the Nazi régimes’s chief racial theorist, having a PhD from Moscow Imperial Higher Technical School. A diffident, uncharismatic man, he had nevertheless stewed and re-stewed a crass mix of anti-Semitism, Aryan superiority, neo-paganism and a rejection of Christianity into something Hitler could pretend was an intellectual and ideological blend. Circumstance had transformed a man who might otherwise have been a narrow-minded crank best avoided at drinks parties into a tutelary angel of genocide.

Perhaps it was not apparent at the time, given the recent nature of the conflict, but to look back at Nuremberg now, nearly 80 years later, it is striking just how odd and inadequate a collection of people had sought out the protection, influence and importance of Hitler’s orbit. It’s observed again and again that the leading Nazis were very far from being blond Aryan supermen; indeed, almost the only senior official who came close was Reinhard Heydrich, blond, blue-eyed, well over six feet tall and with an athletic physique honed by fencing. But he had been assassinated in 1942, dying at 38 of blood poisoning from pieces of his car’s upholstery stuck in his buttocks.

Given all of that, it is easy to see why the western Allies, at least, found something at least relatable in Albert Speer. He turned 40 before the tribunal began, an architect like his father and grandfather, showed no crude signs of ant-Semitism or other toxic manifestations of prejudice, and if people preferred to think of him as an urbane technocrat rather than a ruthlessly ambitious armaments minister who lost no sleep over the fate of slave labour, then he was loath to correct them. He spoke quietly and reasonably at his trial, wrestled very overtly with his conscience and, while he was cynical in creating the image of the “good Nazi”, his prosecutors were probably too naïf in dutifully shuffling down that path with him.

Speer was a liar. His notion that, while he ought to have known about the Holocaust, he did not, was a fiction: he had been at a conference at Posen in 1943 at which Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, had made no secret of the real-world conclusions of the Endlösung der Judenfrage, the Final Solution to the Jewish Question. For a while, Speer claimed that he had left the hall for the most explicit parts of Himmler’s address, but in 2007 a letter was discovered which Speer had written to the widow of a Belgian resistance fighter in 1971, in which the “good Nazi” was very clear: “There is no doubt—I was present as Himmler announced on October 6, 1943, that all Jews would be killed”. It should have surprised no-one. How could a man who had been in the Führer’s inner circle since the mid-1930s, and who had spent the last three years of the war literally equipping the Wehrmacht to continue fighting and to maintain and defend the Third Reich, how could that man have known nothing of one of the régime’s biggest projects, the systematic murder of six million Jews, as well as the slaughter of eight million Soviet civilians and prisoners of war, three million Poles, half a million Roma and Sinti and half a dozen other targeted groups? Of course he knew.

And yet. I find it hard to imagine that Speer was the most evil of the defendants at Nuremberg. Sereny certainly spared him no responsibility in her biography, affirming what other historians had said about his dishonesty and concealment of the extent of his knowledge of the Holocaust. Speer confessed to her that he had been guilty of “tacit acceptance” of what was happening, and she noted, with devastating mildness, “if Speer had said as much in Nuremberg, he would have been hanged”. Nor was Sereny an innocent. In 1970-71, she had conducted a series of interviews with Franz Stangl, commandant of Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps, in the wake of his conviction for the murders of 900,000 people (yes, that figure is correct). She had sat with, talked to a man of unbelievable brutality and wickedness, and she had watched and listened as his psyche had gradually collapsed like a star folding in on itself.

My conscience is clear about what I did, myself… I have never intentionally hurt anyone, myself… But I was there… So yes… in reality I share the guilt… Because my guilt… my guilt… only now in these talks… now that I have talked about it all for the first time. My guilt is that I am still here. That is my guilt.

Those were Stangl’s precise words to Sereny. The above passage took him more than half an hour to get out. Nineteen hours later he died of heart failure.

Sereny said again and again that she loathed Stangl, that she as happy he had died; perhaps in some metaphysical way she had killed him. Yet she would not say that he was evil, a proposition to which few others would have hesitated to attest. Speer by contrast she confessed to liking, without minimising what he had done. She was fascinated by what she saw as his struggle towards some kind of moral redemption; indeed, she would write of the period after they first met in the 1970s, “I fully believed, and loved, that feeling of guilt in him”. For all that, though, when he died in 1981, she didn’t mourn.

I was not sad. He had given me a great deal of himself, of knowledge and of understanding, and I was grateful to him for that. No one else could have given me what he did; there was no one else who knew and understood as much as he did. But when he died, I thought that his death was right and, in a terrible way, overdue; fate had given him 35 years after the Nuremberg trials, at which he should probably have been sentenced to death, as were others perhaps less guilty than he.

Perhaps I’m over-complicating this. Speer was a wicked man, who lied about the blood in which his hands were steeped, and, when found out, tried to moralise his way out of guilt. Certainly he was not the “good Nazi” of the legend he had tried to construct. Yet there is surely a chasm between what Speer had known about, accepted, tolerated, tacitly endorsed, and what, for example, Stangl had done and ordered and overseen.

The extent and depth of guilt of the German nation for the Holocaust has been argued back and forth by historians for eight decades. The highest watermark of responsibility was set out in Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s 1996 volume Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust, which stressed a unique Germanic anti-Semitism that had allowed the staggering brutality and prejudice against Jews and others to take place. Some authors since have criticised what they see as Goldhagen’s weak research basis, and executive championing of neighbours. Even if we regard Goldhagen an extremist, the notion that every contemporary German carried at least some biomarker of hatred is prevalent, and seems to make sense.

If we judge Speer again the standards of other senior Nazis, he was certainly more charming, intellectual and courtly. Equally, however, the stain of guilt must be on everyone, not just a few. But if one tries to imagine the atmosphere of that period immediately after the war, it must have been a titanic undertaking even to absorb the scale of the evil that had been done, let alone how to dole out different shades of responsibility.

In the end, I think it should hearten us that from the cataclysm of the Second World War we were able to construct an imperfect but rational system of pursuing justice, and which really begat the modern system of international criminal law. No Nuremberg, no trials over Yugoslavia or Rwanda, and no International Criminal Court. Not only did we witness the birth of this form of jurisprudence, but the system proved robust enough that within its confines we could also consider not just matters of legal liability but also of moral guilt and responsibility. That is no small thing.