You needn't be so scared. Love doesn't end

I have mentioned my mother occasionally in these essays, but she deserved (at least) one to herself

My mother died on 29 April 2020, at about 2.15 pm. For whatever reason, the date itself never sticks properly in my head, and, to my embarrassment, I always have to check. I know the month and year, obviously, but that number 29 just won’t remain in my head. I don’t suppose it matters; I’m certain she wouldn’t have minded.

She was terminally ill. By which I mean she was suffering from an incurable (and rare) cancer which would, we all knew, kill her at some point. Her decline that April was swift and a little unexpected, and her hospitalisation with shortness of breath—there was cancer in her lungs by then—was unhelpful, as, at the early stage of the pandemic, she caught Covid-19 in Sunderland Royal Hospital. It appeared on her death certificate as a cause, but I don’t really feel fully that “my mother died of Covid”, as she was in the final straight anyway. And it suits me not to dwell on that aspect of her death.

I was in London when she started to deteriorate quickly and was moved to the marvellous St Benedict’s Hospice, the same institution which had looked after my (paternal) grandfather as he waited for the final, fatal blow of throat cancer. Ma had visited him daily, despite by then being divorced from my father, and had come to like and respect the calm, practical approach to death which they embodied. So we had all known that, if she were ever to need palliative care, she’d want to go to St Benedict’s. And so she did.

(This lecture, by B.J. Miller, is by a long way the best TED talk I’ve ever seen and is a beautiful meditation on the importance of how we die. I cannot recommend it highly enough.)

Ma was not in the hospice long: only one night, I think. I arrived in Sunderland to see her settled in and Steve, my stepfather, and I took turns being with her, although she slept a lot. The following day the doctors felt she was near the end. On day one, she had been tired but awake and even trying to joke, remarking how comfortable the accommodation was; by day two, she was largely asleep. The nurses warned me that at some point the sleep would just deepen and then become permanent, and I braced myself for that. Better, I thought, and think, that gentle exit than something dramatic or, God help us, grand guignol. I don’t think she was afraid. Although she held tentatively to some strands of Jewish custom, she hadn’t been raised in any religion, her only real sentiments in that regard being old-fashioned but instinctive anti-Catholicism which stemmed from her west of Scotland upbringing.

It’s worth saying something about that, because it doesn’t really compute with people who don’t know the west of Scotland and Glasgow or, even more so, Northern Ireland (somewhere Ma never visited and had no desire to go, taking a plague-on-both-your-houses attitude towards the Troubles). I sometimes use her quirks of instinct as jokes and funny lines, especially with people who know the culture, and they were peculiar. She didn’t like the idea of Catholicism, disliked celibate priests and found issues like abortion and paedophilia useful sticks to beat the Church of Rome with. She could be mocking of Catholic friends, even if they didn’t believe very strongly, and she was bemused (at best) by her only son’s fascination with Catholicism and academic study of its history. I once on the spur of the moment described myself as “Catholic-curious” on a TV programme, and, although it was flippant, it wasn’t a bad description of how I view what (oddly) I often call Holy Mother Church.

For her, coming from the culture she did, religion was inextricably tied to social class. As a young girl in Wishaw in the 1950s, she had known virtually no middle-class Catholics because there were virtually none to be known, and she recalled the arrival of a Catholic headmaster and his family with curiosity, as they had been the first Roman “our sort of people” she’d ever encountered. She had known a pair of twins, the Feeley girls, with whom she’d played as a young girl, but eventually her mother, my lovely, benign, dippy grandmother, had told her she was no longer to keep their company, because, Grandma said, they lived in a prefab and their father (a postman, I think) had suffered from TB.

That was untrue. He may have been a postman, and they may have lived in a prefab, but the injunction had been handed down because the Feeleys were, no prizes for guessing, Catholic, and my grandmother, out of habit rather than malice, did not want Ma playing with them. Although my distaff side has Jewish roots, it was uncontroversial, indeed, unquestioned, that they were Protestant Jews rather than Catholic Jews if it ever came to it. In later life I worked for a successful Jewish Glasgow businessman in my stint in PR; he is an avid Celtic supporter, and Ma found that impossible to believe. Why would you choose to ally with Catholics if you had the free choice? (Her views of Celtic fans when they rarely came to Sunderland to play at the Stadium of Light were, shall we say, pungent.)

Strange little nuggets of west-of-Scotland lore were passed to me unconsciously. Ma had three particular beliefs, none of which made much sense to me except in a very broad class-based way: Catholics, she was sure beyond peradventure, did not keep their front steps clean; they ate in the street (she never did); and they wore pairs of shoes until they were ready to be thrown away, rather than having them mended. All of these, I suppose, could be linked to an association between Catholicism and poverty, which was strong in and around Glasgow. My aunt (Ma’s half-sister) was the same. She had Parkinson’s disease for decades, and bore it with quiet dignity; her great hatred was a fuss being made, but eventually she had to accept, a few years before she died, the services of a home help for a few hours a week. Inevitably, the home help was a Roman, and I’m sure Aunt Sheena was nothing but polite, but she confided to my mother the extraordinary phrase “Do you not find Catholics have an edge to them?”

I remember upending Ma’s mental world by revealing to her—history was not her forte as she has disliked her history teacher but benefited from a good-looking geography teacher (not that her geography was very good either)—that all of Scotland had been Catholic for centuries before the Reformation of the 1500s. At first she was genuinely reluctant to believe this, but once I explained, she decided that she must simply have missed the class in which they had taught the Reformation (and, presumably, all Scottish history before the dreadful John Knox).

Like many instinctive prejudices, it often didn’t survive contact with the enemy. She had real friends who were Catholic, and seemed to be able to perform some kind of dissociative feat of distance between them and the religion they followed and she disliked; she liked by reputation some of my very close friends like Mike Hennessy, a House of Commons colleague and dear friend who is very devoutly Catholic and has eight children to advertise it; and, although my partner for many years, Jenny, was from a mixed confessional background in Northern Ireland, Ma never showed any curiosity about the Roman half (and Jenny never really disclosed much of her beliefs, if she had any religious ones; I forgive anyone from Northern Ireland for just not getting into the subject).

I can’t leave this subject without mention of Uncle Jimmy. My maternal grandmother was one of 13, I think, and one brother, Jimmy McLean, was known to be somewhat eccentric. Even for his time and place, he has pronounced views on Catholics, naturally in the negative; he was convinced that the BBC (perhaps both television networks?) was part of a conspiracy only to feature good-looking Catholics, to make it seem, apparently, as if Catholicism was somehow more acceptable than he thought it was. His special bête noire was the late Eamonn Andrews, host of What’s My Line?, Crackerjack and This Is Your Life, who was—for younger readers—a pleasant-looking and charming Dubliner, but who, in Uncle Jimmy’s view, “had the map of Ireland stamped all over his face”, and was given far too much prominence. (As an observation, it was not wholly inaccurate: Andrews, whom I remember quite fondly as a benign TV presence, did look very Irish and had what I call, with the assent of some Irish and Irish-descended friends, “a big Irish face”. There is a particular physiognomy to some of Erin’s sons and daughters—my friend Andrew Cusack, New York-born but a citizen of the Republic, knows what I mean—and Andrews fell, with whatever effect, into that category. But Uncle Jimmy disliked the whole business and found it sinister.

I’ve been conscious for some years that tales I tell of Ma, particularly in later life, make her sound eccentric and ditzy. She played it up herself, lamenting forgetfulness or her inability to remember jokes (at that she was admittedly terrible), but it was a nonsense. Ma was fearsomely clever and acute. She had got a first from Edinburgh in education and knew the canon of English literature well: indeed, she had often helped my father—they had known each other since childhood—with his English essays, as he had no taste for literary fiction, while Ma rather liked helping, especially if she could make it out to be a chore which she endured for the good of her soul.

I don’t know if she had always wanted to be a teacher, but I suspect so. After a term (maybe a year?) as a non-qualified teacher of theology, of all things, in Scotland, she had set her sights on the education of troubled children. Unusually for a woman, she taught for a while at Newton Aycliffe Approved School in County Durham; it seems an archaic term now, “approved school”, but these were residential institutions where courts could send young people either after commission of a crime or simply because they were utterly unamenable to parental control. It was hard work and entailed long hours, as well as a degree of physical danger, but Ma, from what she told me, thrived on it. She had been in her twenties and full of energy, and had taken like a natural to the task not only of controlling and monitoring but educating the “bad” boys and girls (almost always boys, as it happened). Aycliffe was notorious. It was known as “the Eton of child crime”, and a newspaper report from the early 1990s, decades after Ma had moved on, described one boy who had committed aggravated rape with a screwdriver, while another had been abused for years by a family member and had brought his ordeal to an end buy buying a knife and stabbing his abuser to death: at 16, the boy predicted casually he would “graduate” to prison.

When I was young, I never really thought very hard about Ma’s job. Intellectually I knew what she did, and sometimes, if my school holidays outlasted hers, she would take me along to work (this was after Aycliffe, when she was running Eastfield Unit in Sunderland for disruptive older teens) and deposit me in her office with paper and pens. I would see the pupils, much older than me, but was never, so far as I recall, frightened or intimated, assuming without thought that they were under control and seeing the deference they showed Ma as the headteacher.

I do remember simply taking it for granted from a young age that I could not do what she did. As a rather didactic child (a habit I haven’t shifted, unfortunately for my friends), the idea of a career in teaching occasionally surfaced in my head, but the images were always of my small, quiet, uneventful prep school, or else the schools I read about in fiction, never anything as challenging as what Ma did. So it was simply a thing, her job, unexamined in any detail by me.

She inspired fierce loyalty in her staff, and if I have learned anything from her I hope it includes the drummed-in instinct that you look after your team, watch their backs and stand up for them against any external pressure. I certainly tried to follow that example when I was managing teams in the House of Commons, and, while I’m sure I often failed, my motivation was, I think, good and benign.

Now I am middle-aged and can examine it from the distance of time, it must have been stressful and demanding, but I never saw her daunted. Ma was not tall—she might have clipped 5’6” on her best day when young—and, although she became wispily slender in middle age, she was never stocky. That seemed not to intrude on her consciousness at all, except in amusement once I became obviously larger than her at quite a young age. (When I was ill, back in 2018, she took me to the optician; the man sitting next to her as I went off for my eye test said slightly doubtfully “Why, that’s a big lad. Is he yours?” Ma affirmed that I was. “Are ye sure?” he asked. She said she was fairly sure.)

It feels fraudulent to rate and classify her work experiences without consultation, but I have to do what I can. For a time she taught English at Ryhope School, and I know that was a happy experience. The colleague showing her round said “You’ll love the head of English.” She did, and she and Steve began the relationship which would endure until her death 37 years later, and which—happily for them—set me a ridiculously high standard for adoration and contentment. Although very different people, they revelled in each other’s company and I rarely saw irritation or cross words over all the long years. My father remarried and he and my stepmother, Judy, also had many happy years together until he too succumbed to cancer in 2017, but it is perhaps the greatest satisfaction of my life that Ma and Steve found each other and never looked back. They made each other intensely happy, and that was, and is, good enough for me.

I think her most contented period of professional life was running Maplewood, a special school in Sunderland. She more or less relaunched it when she took over in the late 1980s, and made it an extraordinary place. Dealing in children primarily with emotional and behavioural difficulties (as opposed to learning difficulties), it was her joy and her perfect milieu. For some reason, she understood the children who passed through her doors, those who were, in the parlance of the time, unacceptable now, “mad and bad”. They had been excluded from mainstream schools for all sorts of reasons—memorably, one of the rare girls had bitten the head off the budgie belonging to her previous school—and she could divine exactly what balance was possible between management and containment on the one hand, and education on the other.

It required clear-eyed and somewhat ruthless assessment. Maplewood was always an institution of learning, but, while the notional aim was to return the pupils to mainstream education, it was a goal which was simply unrealistic for many of them. Some would, Ma knew, be taught under her care and then moved on to a senior part of the special system. Of course there were triumphs of children reintegrated, but some were so damaged or disruptive that that was simply a chimaera. I remember her speaking—discreetly—of a young girl who had been passed around her housing estate for sexual abuse while still young enough to be in a pushchair, with the connivance of her mother; that girl was unlikely ever to be able to fit in to a mainstream school so Ma simply acknowledged that, until she left at the appropriate age, Maplewood would be her schooling. And the staff got on with that task brilliantly.

Conduct and discipline in schools are hot topics these days, especially when it comes to people like Katharine Birbalsingh and her Michaela School which focuses on order and obedience (the new home secretary, Suella Braverman KC, was its first head of governors). Ma was not evangelical particularly—though away from work she would sometimes comment not very sotto voce on the behaviour of children she encountered in shops and so on—but she certainly valued discipline and neatness. Maplewood had a simple uniform of sweatshirt, polo shirt and trousers or skirts, and it was inexpensive because she knew that many of the parents were poor, but that uniform had to be worn neatly and correctly, and she was strict on other matters of appearance: earrings were absolutely verboten, parents advised that they could have their children’s ears pierced at the beginning of the summer holiday if they wished but there would be no jewellery, not even sleepers, when term began; and she waged a personal war against “extreme haircuts”, which meant anything dramatically shaved, too long or otherwise noteworthy, and she was quite content to send pupils home until they were acceptable in appearance.

This did not always sit well with parents who, if I may be judgemental for a moment, did not always step up to the plate of basic childcare but felt in other regards very entitled when it came to their offspring’s rights in a school context. Ma’s reaction was always the same. She was happy to explain the rules in person to irate parents, and was always scrupulously polite, but she took the view that the rules—her rules—were clearly set out and parents made aware of them, and there would be no variations or exemptions. Parents could and did shout, scream, threaten and abuse, but the result was always the same: compliance, as the foundation of order and discipline.

I wouldn’t say Ma was argumentative or self-righteous, but she was certain of her ground and unwilling to yield. She and I very occasionally butted heads in that respect (I can be dreadfully stubborn, a bad habit which I try to mitigate) but, by the time I was a proper adult, assuming I am at all, I became much better at avoiding pointless arguments. She was difficult to persuade and would sometimes prefer just to sulk, and I lost my taste for arguing with her at an early age. (In fact, for someone like me, who enjoys debate, she was no fun to argue with; for Ma, a champion debater in her youth, it was a matter of winning or losing rather than persuasion or exchange of ideas, whereas that kind of intellectual tussle is, for better or worse, often my idea of heaven, and I hope I am usually big enough to concede if bested. Ma didn’t like that.)

On education, she was certain of her ground, being clever and experienced, so debate was rarely the mot juste; with parents it was argument, and she would win. In a professional context she would never, or almost never, take it personally. Outraged parents could scream the most appalling things at her but she was unruffled. That wasn’t a game she would play, and she knew how to win. (Later in life, while walking one of our dogs, she pointedly asked another owner to pick up his dog’s faeces and put it in a bag. His retort, blunt and uncomplicated, was “I’m not carryin’ a bag of shite round wi’ me, ya skinny cunt.” She came home floating on air at the use of the word “skinny”.)

Ma used to say that she didn’t really like children, despite her profession. I think in some ways this was true. I say without blushing that she adored me, her only child, though it was not uncritical adoration: she knew my faults as well as anyone, was exasperated by them and also knew the buttons to press to rile me. It was probably my fault more often than not. But—and I’ve thought a lot about this since she died—however much I had disappointed her, and I did, often, I never doubted for a second that I was still loved, her emotions not remotely diminished by any irritation or feeling of having been let down.

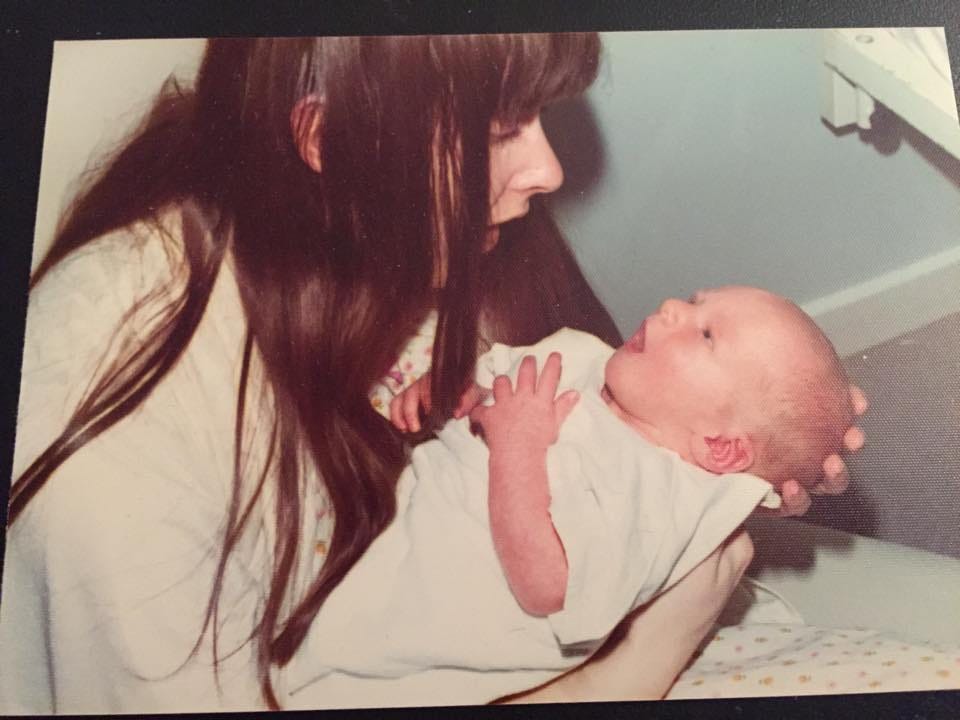

That was a powerful thing, though I see it more in retrospect than I did at the time, when I suppose I took it for granted. She had yearned for motherhood, and it had not come easily. Even in my case, I was born slightly early by caesarean section, as she had broken her back not so long before in a car accident and was advised against the rigours of a natural birth. At least I have always known I could kill Macbeth if it came to it. In addition, I was a breech baby, typically awkward, legs pointing south as if I had no wish to emerge any time imminently.

Through the various crises I have endured and manufactured, I was always certain that Ma would be there. She might not be in a good mood, and she might not spare her extensive and withering criticisms, but they were simply the clothes in which her love came. The love itself was absolutely assured.

If I owe Ma a lot situationally, for every time she was there to cushion some stupid fall or stumble I had arranged, personally or professionally or academically, I owe her a lot more too. If I am clever at all—this isn’t false modesty, I know I have a type of cleverness but it tends towards glibness and relies on a good memory—a lot of that is from her.

My father, a psychologist who ended up as chief executive of an NHS trust and whom I loved powerfully and dearly, certainly gave me a certain rigour of thought. He was by no means a pure scientist: he was sceptical about much of the mental health profession but was, I’m told, a bloody good shrink, and was for a while a member of the Mental Health Act Commission, a body which supervised patients detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 and assessed whether their care continued to be appropriate. This took him to some of the grimmest parts of mental health, the high-security psychiatric hospitals of Rampton, Ashworth and Bradmoor, where impenetrable cases like Ian Brady and Peter Sutcliffe were to be found. This was not work for the faint-hearted.

If Ma was clever, she was also creative. She and my stepfather authored a series of textbooks for writing, Write On (I believe still available, if you want to boost the tiny royalties!), another set called Focus Stories, a children’s novel, Jackson, and another YA novel, The Bonny, which was loosely based on an annual bonfire on the triangle of grass behind our house. If their works never quite caught the imagination like Jo Rowling’s, nevertheless they were much used in schools, and Ma and Steve enjoyed writing together (a process I find difficult and irksome). Ma wrote for pleasure too, always in longhand, always on a pad of paper on her knees, and was very good at what is now the young adult market. As we were sorting through her belongings after she died, Steve found what seems to be a full manuscript and had it digitised: I have started editing it, insofar as I can, and it would please me hugely if something can be done with it as a final and very fitting tribute.

The writing bug was certainly passed on to me. I have always created stories in my head, for as long as I can remember, often absurdly detailed and complex; last year, finally accepting that I could call myself simply a “writer”, as I am paid to produce words, I wrote a piece on my LinkedIn profile about why people write, taking as its title the axiom of Ernest Hemingway, “All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” Friends, some of them writers, were kind enough to say it had struck a chord with them and I am quietly proud of it, because I think it goes some way to explaining why writers write. Very often the answer is simple: we have to. Not for money or professional satisfaction, but just because we need to write.

I don’t know if Ma felt the pain of being a writer. Like me, she wrote quickly, and she rarely seemed wracked by the process as I sometimes am. But it brought her pleasure, as it does me, and I think there was a degree of compulsion to her writing. If I can imagine further, I think, as I do, she wrote to make sense of the world and to process her thoughts and emotions. It’s not merely a matter of describing them, as I am haltingly doing here, but sometimes we—well, I—have to fictionalise our experiences, impose them on our characters, before we can really see what they have meant and how we can deal with them. In part it’s the explanation for the roman à clef and the lightly disguised fiction, and why authors are so often accused, not without reason, of identifying with or pouring much of themselves into their protagonists. To take an example, as I am finishing the Kingsley Amis “continuation” Bond novel Colonel Sun, Ian Fleming certainly used 007 as a way to work through his ambitions, interests and fantasies. I don’t think I am so very different.

If Ma gave me writing through her straightforward example, she and Steve (with whom I lived, though I saw my father and stepmother most weekends) gave me an environment in which reading was simply part of the ether. Partly through shyness and partly through precocity, I read a lot as a child: precocious not in that I was reading Dickens or Hardy or Austen (I adored thrillers and espionage, from Fleming to Jack Higgins), but in that I knew a lot of words, was rarely confounded and had a high reading age. But reading was also simply something one did. I can remember afternoons at home when each of us would be in the same room, largely silent, reading our respective books. That to me was absolutely normal (and lovely).

I know I was lucky in that respect. Since both Ma and Steve were at heart English teachers, there were always books around if I strayed from my own diet, and each would make gentle recommendations. I was a devotee of the local library in Sunderland (the foundation stone of which, bizarrely, was laid in the presence of a post-presidency Ulysses S. Grant, who I can only assume was badly lost or misled), and I pounded the photocopier to bring home sheaves from reference books without a care for copyright or licensing, the machine showing a great thirst for 10p pieces.

Reading was simply everyday. It was pleasure, intrigue, pastime, learning. In those years before the Internet, books had the answers to questions you wanted, and I was as curious as a child as I still am an adult. I hoard and inhale knowledge, most of it probably useless, and luckily I’m able to retain a lot of it. I just like knowing things, and if I encounter something unfamiliar or unknown, I’ll seek out information. It’s a million times easier now, of course, but I do it on Google just as I did in encyclopaedias and dictionaries and textbooks. Learn, learn, learn: cram in all that new information as much as you can.

To save this from complete hagiography, Ma was not quite like that. Extremely intelligent and learned, she was not so curious for curiosity’s sake. She was rarely tempted to read fiction outside her preferred sphere—mainly thrillers and crime novels, often first-class, devoured at a prodigious rate—and she shunned anything that had a scent of “literary” fiction or seemed, as she would put it, “hard”. She could be difficult (though not impossible) to recommend books to, as she made snap judgements on whether or not they were her “sort of thing”, and would not generally go back on those first impressions. (She also had a firm rule about novels featuring dogs: she couldn’t bear to read about cruelty to animals, so would flick to the back of the book to make sure the dog survived.)

But she was intensely curious about people. She would overhear snatches of conversation, sometimes superficially improbable, and want to know more: who was who, how their interactions worked, what was the backstory. Perhaps it’s fairer to say she was at heart a storyteller as much as a writer. She claimed, wrongly I think, that I was a better writer, but if there is any truth in that, it is only in that I get more pleasure than she did from the fitting together of words and the selection of them. She was driven by narrative more than by process, and that is something I envy.

This brings me unexpectedly neatly to one more thing I should say. I am set in my ways sometimes, and I often crave routine and familiarity: Ma used in later life to tease me by holding her fingers together and muttering “You missed the spectrum by that much.” Perhaps it’s true, though I steer clear of appropriating medical diagnoses unless I have pretty firm evidence. But, more even than me, Ma did not like change, and that grew more true as she got older. She preferred her own and Steve’s company to other people’s, liked being at home rather than in the pub or a restaurant (the opposite of my weirdly solitary congeniality) and was not keen on novelty.

You saw this in holiday destinations. She and Steve would find somewhere they liked—loved, really—and it would be their regular retreat for years. There was neither rhyme nor reason that I could discern, but they adored Amsterdam (always on the overnight ferry from North Shields), then the improbable playground of the rich in Puerto Banús, then, most satisfactorily, New York, where Ma felt at home in a way she may never have done anywhere outside her own home. (I have just come back from Gotham after my first ever visit, a shameful fact at the age of 44, and I loved it; I see, I think, what attracted her and Steve.) In their chosen location, much would be repeated for the comfort of familiarity: the same coffee shop, the same hotel, the same streets and squares.

I think I am more adventurous than that, though for 15 years I tagged along with my father’s family to New England; different parts, but always the same feel. And cities I love, like Boston and Dublin and Edinburgh, I could, and do, visit again and again. There’s always more to see and discover. There are dozens of places I want to travel to: my diet thus far in life has been a strange mix of the unextraordinary but lovely—Paris, New Hampshire, Italy—interspersed, largely through work, with the more unlikely—Baghdad, Kuwait, Dubrovnik, Stockholm.

This has wandered and sprawled and uncovered things I had not anticipated. It is by no means a complete tribute to, or even description of, my mother. But it has helped me and I hope is of some interest both to those who knew her and those who didn’t. After she died, I endowed a very modest prize for creative writing at her alma mater, the University of Edinburgh. She was happy there in the late 1960s and I think she would approve. It may grow in stature as and when circumstances allow; for the moment, it gives me some satisfaction that young students will get a small mark of esteem for their work and perhaps, for a little, wonder who she was and why the prize is there. I wrote a short biographical paragraph for the Alumni Office to set the scene, but, as this essay amply demonstrates, Ma was not easily to be summed up. So I shall, in time, return to her.

A lovely tribute to a remarkable woman.

I loved your mam and was lucky enough to work on a couple of SEN projects with her for South Tyneside Council. We really, really got on well. She nicknamed me 'Sparky' and when I left the authority gave me a print by McGuinness having learned mining was a huge part of my own ancestry. I loved this piece, you brought her back to life for me. I really miss her.