Sunday round-up 25 May 2025

The anniversary of the Edict of Worms, the resignation of the last Lord Protector and the return to England of Charles II & birthdays for Ian McKellen, Alastair Campbell, Paul Weller and Julian Clary

Today’s birthday ducks and drakes include veteran producer and director Irwin Winkler (94), former Labour MP, minister and Lord Mandelson’s unofficial mortgage lender Geoffrey Robinson (87), legend of stage and screen Sir Ian McKellen (86), puppeteer, film-maker and actor Frank Oz (81), historian and activist Marianne Elliott (77), Scorpions front-man and no stranger to a leather hat Klaus Meine (77), Back to the Future co-writer Bob Gale (74), former TimeWarner grand fromage Jeffrey Bewkes (73), playwright and activist V (formerly Eve Ensler, I don’t make the rules) (72), journalist, podcaster and splenetic spinmeister Alastair Campbell (68), singer-songwriter, musician and Modfather Paul Weller (67), comedian, author and alleged Norman Lamont-fister Julian Clary (66), permacheerful, only-blown-up-once presenter and chocolate-sponsored bride Anthea Turner (65), actor, singer, writer and master of fewer accents than he imagines Mike Myers (62), model and actress Molly Sims (52), chiselled-of-feature actor Cillian Murphy (49), England and British & Irish Lions rugby union legend Jonny Wilkinson (46), dynastic racing driver A.J. Foyt IV (41) and Olympic gold medal-winning cyclist Geraint Thomas (39).

Those for whom the balloons have deflated and the candles have gone out include much-lampooned first Tory Prime Minister the Earl of Bute (1713), author, playwright and cabinet minister Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803), poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803), icon of cultural history and historiography Jacob Burckhardt (1818), pioneer of modern Albanian literature Naim Frashëri (1846), First World War commander Marshal Louis Franchet d’Espèrey (1856), journalist, art critic and one of Oscar Wilde’s lovers Robbie Ross (1866), businessman, newspaper owner and cabinet minister Lord Beaverbrook (1879), Jesuit priest, writer and scholar C.C. Martindale (1879), neurologist Jean Alexandre Barré (1880), Operation Rheinübung commander and went-down-with-the-Bismarck Admiral Günther Lütjens (1889), aircraft designer Igor Sikorsky (1889), country music pioneer Ernest “Pop” Stoneman (1893), world heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney (1897), Random House co-founder, television personality and What’s My Line? stalwart Bennett Cerf (1898), Second World War fighter ace Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich Bär (1913), journalist and television presenter Richard Dimbleby (1913), songwriter and composer Hal David (1921), best-selling author Robert Ludlum (1927), fashion designer Sonia Rykiel (1930), novelist, screenwriter and critic John Gregory Dunne (1932), short story writer and poet Raymond Carver (1938), novelist, historian and critic Margaret Forster (1938) and actress Anne Heche (1969).

Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me

Today in 1521, the meeting of the Reichstag convened by the Emperor Charles V in the Imperial Free City of Worms concluded. It had assembled in the Bischofshof, the episcopal palace next to the cathedral, on 28 January in order to consider the case of Martin Luther, the Augustinian friar and Professor of the Bible at the University of Wittenberg, who had been excommunicated three weeks before by Pope Leo X by the papal bull Decet Romanum Pontficem.

On 31 October 1517, Luther had published a series of challenges to Roman Catholic doctrine, formally titled A Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences but better known as his Ninety-Five Theses, which had led eventually to Leo issuing a papal bull, Exsurge Domine, in June 1520. In this, the Pope had instructed Luther to recant 41 sentences from his various writings including the Ninety-Five Theses within 60 days or risk excommunication. Rather than recant, Luther had publicly burned the bull and the Decretals of Canon Law in Wittenberg. His excommunication had followed swiftly, but he was given a final chance to reconsider. He enjoyed the patronage and protection of the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (about whom I wrote recently for Engelsberg Ideas), and the Emperor himself erred towards finding some politically convenient compromise. In any event, his excommunication and the condemnation of his writings had been issued by the Church but only the secular authorities, the German princes, could enforce them. So Charles V summoned the Reichstag, the Holy Roman Empire’s unwieldy legislature, to Worms to decide how to proceed.

Luther arrived at the Reichstag on 16 April. Mindful of the fate of the Bohemian reformer Jan Hus at the Council of Constance in 1415 (he had been burned at the stake), Frederick secured a guarantee of safe passage to and from the Reichstag for Luther. Masterminding the case against Luther was the Swabian priest, theologian and protonotary apostolic, Johann Eck. Initially enjoying cordial relations, Eck had become a vehement opponent of Luther, clashing in print and besting Luther’s Wittenberg colleague Andreas Karlstadt in a public disputation in Leipzig in 1519.

When Luther was eventually summoned before the Reichstag at 4.00 pm on 18 April, he explained to Eck that he could not recant what he had written because to do so would simply be to encourage further abuses within the Church and to encourage the suppression of dissident voices like his. He conceded that, if he could be shown by reference to Scripture that he had erred in his statements, he would be prepared to reconsider, but under no other circumstances.

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.

According to tradition, though he may or may not have used the words, he concluded with a half-defiant, half-apologetic declaration: Hier stehe ich; ich kann nicht anders. Gott hilf mir. (“Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me.”)

Eck told him he was behaving like a heretic and that appealing to Scripture was not a catch-all explanation.

Martin, there is no one of the heresies which have torn the bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretation of the Scripture. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. It was with biblical texts that Pelagius and Arius maintained their doctrines… When the fathers of the Council of Constance condemned this proposition of Jan Hus—The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect, they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the celestial beatitude.

Luther left Worms on 26 April, but the Elector Frederick arranged for him to be intercepted on his journey back to Wittenberg and taken to safety at the Wartburg, a castle overlooking Eisenach. Meanwhile, there were days of private deliberations at Worms as the princes and other officials decided how to respond, given Luther’s steadfast refusal to recant.

On 25 May, the Emperor issued the Edict of Worms, a decree which condemned Luther. The edict rehearsed Luther’s many heretical views, emphasised the opportunities the Church and the Reichstag had given him to see the error of his ways and recant, and underline his obduracy. “It seems that this man, Martin, is not a man but a demon in the appearance of a man, clothed in religious habit to be better able to deceive mankind,” it concluded. The Emperor declared that Luther was an outlaw and a heretic, and should no longer enjoy any protection.

We have declared and hereby forever declare by this edict that the said Martin Luther is to be considered an estranged member, rotten and cut off from the body of our Holy Mother Church. He is an obstinate, schismatic heretic, and we want him to be considered as such by all of you. For this reason we forbid anyone from this time forward to dare, either by words or by deeds, to receive, defend, sustain, or favor the said Martin Luther. On the contrary, we want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic, as he deserves, to be brought personally before us, or to be securely guarded until those who have captured him inform us, whereupon we will order the appropriate manner of proceeding against the said Luther.

Luther was placed under the Imperial Ban. Not only was he condemned as a heretic, therefore, but he was placed literally outwith the law. He could be killed with no legal consequences. In theory, this fugitive status put him in mortal danger, and he remained under Frederick the Wise’s protection at the Wartburg for several months, spending his time translating the New Testament into German. But the Emperor’s writ did not run without question in the jurisdictional hurly-burly of the early modern Holy Roman Empire. Political considerations intruded and Luther’s heresy, and his own safety, soon became absorbed into much wider struggles. He died at 2.45 am on 18 Februaru 1546, a quarter of a century after his condemnation, aged 62, and he died in bed in his home town of Eisleben, having preached his last sermon three days earlier (it was a vitriolic attack on the Jews, urging that they be expelled from all German territory). So much for the Edict of Worms.

From a corruptible, to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be

Earlier this week, I marked the anniversary of the creation of the Commonwealth of England in 1649. Britain’s experiment with republican government was short-lived and, I’d argue, fairly unsuccessful, mitigating very few of the complaints which Parliamentarians had levelled against the monarchy during the Civil War. That said, as someone who adheres passionately the essential settlement of the Glorious Revolution of 1688/89, I concede that the 11 years of de facto republicanism may have been a necessary catalyst to get us where we are today.

The Commonwealth in its 1649 form lasted only a few years until the Rump Parliament was dismissed by Oliver Cromwell, who became Lord Protector and who would, over the ensuing years, start to look and act more and more like an absolute monarch than many royal predecessors (though he did refuse the Crown when it was explicitly offered to him: King Oliver I?). Cromwell died in September 1658—he is said to have refused quinine to treat the malarial fever which led to his death because it had been discovered by Catholics—and in a totally-different-from-an-hereditary-monarchy way he was succeeded as Lord Protector by his third but eldest surviving son Richard, an undistinguished 31-year-old who had held various offices by virtue of his status as Cromwell’s son and had left a mark on none of them.

Richard Cromwell, nicknamed—and this is very unfortunate—“Tumbledown Dick”, was barely a shadow of his father and had no hope of exercising the office of Lord Protector effectively. He lacked his father’s power base in the New Model Army, and he faced a governmental crisis of debt, which stood at around £2 million (something like £350 million today, which sounds minor!). It was decided to summon a new parliament to address the financial crisis, but the Third Protectorate Parliament, when it met in January 1659, proved an intractable body and impossible for the government to manage. It also attempted to limit the power of the army, which then demanded that the Lord Protector dissolve it. When Richard refused, soldiers were assembled at St James’s Palace to force his hand: on 22 April, he dissolved the Third Protectorate Parliament, then on 7 May he recalled the Rump Parliament, the remaining MPs who had first been elected to the Long Parliament in 1640.

Cromwell’s authority, however slight it had been, was now spent. On this day in 1659, after the Rump Parliament had agreed to settle his personal debts of £30,000 and pay him a pension, he submitted a formal letter of resignation as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, in which he promised to support the régime which came after him.

I trust my past Carriage hitherto hath manifested my acquiescence to the Will and disposition of God, and that I love and value the Peace of this Commonwealth much above my own concernments.

With the Lord Protector gone and with him the Protectorate, control of events passed to the Committee of Safety, originally established in 1642 and revived to replace the Council of State, the Protectorate’s equivalent of the Privy Council. Major General Charles Fleetwood, Richard Cromwell’s brother-in-law and Member of Parliament for Marlborough, was the leading member of the Committee of Safety and soon became Commander-in-Chief, but the whole régime was beginning to crumble. The Commander-in-Chief of Scotland, General George Monck, who had initially supported Richard Cromwell as Lord Protector, had now come to the conclusion that the only way to restore stability was to restore the monarchy. He brought his army south that winter and restored the Long Parliament, which promptly voted to dissolve itself after nearly 20 years, and the Convention Parliament which was elected in April 1660, composed largely of Royalists, began to negotiate for the restoration of the monarchy.

It was on this day in 1660, a year after Tumbledown Dick’s resignation, that Charles II landed at Dover from Scheveningen in the Netherlands. Four days later, on his 30th birthday, he arrived in London to public acclaim and met with Parliament, the first time the Crown-in-Parliament had assembled since the reign of his father, Charles I. Although the Convention Parliament had already declared on 8 May that he was King and had been so since his father’s execution on 30 January 1649, it is this return, 29 May 1660, which is regarded as the Restoration. The republican experiment was over.

Angels and saints preserve us

An eclectic day in the world of hagiography. It is the feast of St Urban I (AD 175-AD 230), Pope from AD 222 to his death in AD 230, the first pontiff whose reign can be reliably dated, who was traditionally believed to have been martyred but seems to have died of natural causes and is invoked by family doctors; of St Canius (3rd century AD), Bishop of Acerenza in southern Italy, who was tortured and put to death during the Diocletianic Persecution for refusing to worship the Emperor and the pagan gods; of St Dionysius (d AD 360), a friend of Emperor Constantius II who became Bishop of Milan before falling out of favour over Arianism and dying in exile; of St Maximus of Évreux (d AD 385), who became Bishop of Évreux and was martyred with his brother Venerandus, a deacon; of St Zenobius (AD 337-AD 417), who became Bishop of Florence, actively proselytised throughout Tuscany, was successful in combating Arianism and reputedly brought the dead back to life in several occasions; of St Aldhelm (AD 639-AD 709), a Wessex-born Benedictine monk and scholar who became Abbot of Malmesbury and Bishop of Sherborne and left behind theological works and poetry in Latin and Anglo-Saxon, and is the patron of musicians and songwriters; of the Venerable Bede (AD 672-AD 735), the “Father of English History” and very possibly born in what is now Sunderland, who spent most of his life as a Benedictine monk at the double abbey of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, wrote and translated theology extensively, composed poetry, pioneered the use of Anno Domini as a dating convention and is most famous for The Ecclesiastical History of the English People; of St Dúnchad mac Cinn Fáelad (d AD 717), grandson of a High King of Ireland who became Abbot of Killochuir then Abbot of Iona; of St Gregory VII (1015-85), Pope from 1073 to 1085, who reformed the papal curia, mandated clerical celibacy, established the Pope’s authority over the Church and emphasised the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist; of St Gerard of Lunel (1275-98), a French aristocrat who became a tertiary of the Franciscan Order aged five, lived in a cave as a hermit at the end of his teens then set out on pilgrimage to the Holy Land but died near Ancona on the Adriatic coast; of St Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi (1566-1607), born to one of the most illustrious noble families in Florence, who learned to meditate, practised mortification of the flesh and took a vow of chastity at the age of 10 then entered a Carmelite nunnery and experienced ecstatic visions which she dictated to her fellow nuns; and of St Madeleine Sophie Barat (1779-1865), born to a prosperous Jansenist family in Champagne, who wanted to become a Carmelite nun but, as the order had been suppressed during the French Revolution, founded the Society of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to educate young women of all classes and saw it spread across Europe, to North Africa and to North and South America.

In the African Union, it is Africa Day, commemorating the foundation in 1963 of the Organisation of African Unity in Addis Ababa. For any Jordanian readers, it is Independence Day, after the parliament of the Amirate of Trans-Jordan ratified the Treaty of London (establishing the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan as an independent state) on this day in 1946.

It is also Geek Pride Day, National Tap Dance Day (in the United States; mirabile dictu, this is laid down by federal law) and, in honour of the late Douglas Adams, Towel Day. Spare me.

Factoids

The British have not always been adept with foreign names, places and pronunciations, but this perhaps reached a peak during the First World War. It may be that so many British and Empire soldiers were sent to northern France and Flanders, finding French challenging enough but Flemish altogether too much. Hence for the soldiers in the trenches the West Flanders city of Ypres (Ieper in Flemish) became “Wipers” in British mouths, the village of Ploegsteert, just north of the French border, was known as “Plug Street” and Auchonvillers on the Somme was rendered “Ocean Villas”. This affectionate mangling extended to people too: the French general Louis Franchet d’Espèrey (see above) was nicknamed “Desperate Frankie”. Less affectionately, though missing a frankly open goal, the commander of the German First Army, General Alexander von Kluck, because of a reputation for hesitancy, was dubbed “Old One O’Clock”.

We have come to a consensus that we regard Sir Robert Walpole as the first British Prime Minister, and date the beginning of the office from his appointment for a second time as First Lord of the Treasury in April 1721. The office of First Lord of the Treasury is now inextricably linked with, fused into, that of Prime Minister (which appears nowhere in statute until the Chequers Estate Act 1917, but in the mid-18th century it was not always simple to identify the most powerful politician in the ministry. Indeed, William Pitt the Elder, 1st Earl of Chatham, is recorded and regarded as having been Prime Minister from 1766 to 1768 while serving as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal; the Duke of Grafton was First Lord of the Treasury 1766-70 and is recognised as having become Prime Minister himself—without exchanging office—in 1768 after Chatham resigned, suffering from some form of mental illness. Yet the ministry which preceded Chatham’s between July 1765 and July 1766, in which the 35-year-old Marquess of Rockingham had been First Lord of the Treasury, was dominated by someone who held no office at all, but could be argued to be the only member of the Royal Family ever to serve as Prime Minister.

Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, was the youngest son of George II (1727-60) and the uncle of George III (1760-1820). He found his calling as a soldier, fighting and sustaining a lifelong injury at the Battle of Dettingen in June 1743 and then, most famously or infamously, defeating Prince Charles Edward and suppressing the Jacobite Rebellion in 1745-46. The ruthlessness with which he not only beat the Jacobite army militarily at the Battle of Culloden in January 1746 but imposing a brutal settlement on the Highlands earned him the nickname “Butcher” Cumberland by his enemies. After resigning all his offices due to a falling-out with his father in 1757, he then became a close and trusted adviser to his nephew after his accession as George III in 1760. When the King dismissed George Grenville as Prime Minister in 1765, Cumberland was instrumental in creating the coalition of so-called “Rockingham Whigs” under the nominal leadership of the young Marquess; the Duke of Grafton and Henry Seymour Conway became Northern and Southern Secretaries, and the Duke of Newcastle was appointed Lord Privy Seal. Cumberland had no official role but attended cabinet meetings, which were held either at Cumberland Lodge, his home at Windsor, or at his London house on Upper Grosvenor Street. One historian has called him “the real Prime Minister”, the force which bound the ministry together and maintained good relations with the Crown. His influence did not last, however, as Cumberland succumbed to a severe stroke and died on 31 October 1765, less than three months into the life of the government.

Many of the areas of modern public policy on which there is most focus, like health, education and welfare, were for centuries not regarded as a matter for the national government. Welfare, governed by the Poor Laws, was administered on a parish basis until the end of the 18th century, while education was a matter for churches, charities and other private organisations until the Elementary Education Act 1870. The first attempt at any central national responsibility for public health was the passage of the Public Health Act 1848, which created a General Board of Health to oversee water supply, sewerage, drainage, cleansing, paving and environmental health regulation. There is a strong sense that the Whig government of Lord John Russell (1846-52) was very much feeling its way i this new area, and perhaps was not wholly committed to the project. Initially the board was to be dissolved at the end of the parliamentary session in which the day five years after the act’s passage fell, though additional legislation was passed to maintain it in 1852, 1853, 1854, 1855, 1856 and 1857; in September 1858, the Board of Health was abolished and its responsibilities transferred to the Privy Council. The board consisted of three commissioners, two appointed by royal warrant, but the act’s provision of a presiding commissioner again indicates the degree of uncertainty and experimentation: the original provision stipulated that the president of the General Board of Health should be the First Commissioner of Her Majesty’s Woods and Forests, Land Revenues, Works, and Buildings, whose “day job” was the management of the Crown Estate. In August 1851 that role was divided in two, and the presidency of the Board of Health fell to the First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings, then the Public Health Act 1854 reconfigured the board under a President appointed by the Queen. So, there you have it: the first national minister for health was the First Commissioner of Woods and Forests.

My mind turned recently, because it does, to what the shortest existence has been for a ministerial post of cabinet rank. There are all sorts of provisos: does renaming count, or must the responsibilities be different? Must it have a department attached? Nevertheless, I will open the bidding with the Secretary of State for Burma, ministerial head of the Burma Office, which existed from August 1947 to January 1948 and was only ever held by the Earl of Listowel. The Burma Office had been created on 1 April 1937 under the Government of Burma Act 1935 to oversee the administration of Burma, which was established as a Crown Colony, and it was constitutionally separate from the India Office, though they shared a building and were headed by the Secretary of State for India and Burma. When India became independent in August 1947, Listowel became simply Burma Secretary, but the Burma Independence Act 1947 was granted Royal Assent on 10 December 1947 and the country became independent on 4 January 1948. The ministerial role was abolished and the remaining personnel from the Burma Office were transferred to the Commonwealth Relations Office. It had lasted for 143 days.

Local government is an area of responsibility which has long proved very difficult to pin down satisfactorily. From 1871 to 1919, the President of the Local Government Board oversaw local public health, vaccinations and the prevention of disease, poor relief, registration of births, marriages and deaths, local taxation, drainage, planning, local improvements, some roads and utilities. When the Local Government Board was abolished, many of its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Health. In 1943, a Ministry of Town and Country Planning was set up, but in January 1951 it took back some functions from the Ministry of Health and became the Ministry of Local Government and Planning. The Conservative government which took office in October that year renamed it as the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, which in 1970 merged with the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Public Building and Works to become the Department of the Environment, one of Edward Heath’s super-ministries. However, from October 1969 to June 1970, Anthony Crosland held the post of Secretary of State for Local Government and Regional Planning; he did not run a department but supervised the Minister of Housing and Local Government and the Minister of Transport, though Prime Minister Harold Wilson left the door open to “the changes which, in [Crosland’s] view, should be made at a later date with a view to creating a more integrated Department”. Eight months later, the Labou Party lost the general election and Crosland’s role was abolished, though Heath’s Department of the Environment is probably along the lines of what Wilson and Crosland had in mind in the longer term.

Wartime drives innovation and experimentation in Whitehall; sometimes it is successful, sometimes it fails, and sometimes it is only necessary during the period of conflict. In October 1939, just after the outbreak of the Second World War, Neville Chamberlain combined the Sea Transport and Mercantile Marine Departments of the Board of Trade with responsibility for merchant shipbuilding into the Ministry of Shipping. It encompassed most aspects of merchant shipping, together with responsibility for foreshores, navigation and the coastguard service, and was headed by Sir John Gilmour, a former Home Secretary (1932-35), Unionist MP for Glasgow Pollok and leading member of the Orange Order. He suffered a fatal heart attack in March 1940 and was succeeded by right-wing Conservative MP Robert Hudson, who was then moved a few weeks later when Winston Churchill became Prime Minister, and Ronald Cross, a merchant banker from a family of wealthy cotton merchants who was MP for Rossendale in Lancashire, was appointed Minister of Shipping. He was not a success, attracting heavy press criticism, and the Ministry of Shipping was merged with the Ministry of Transport on 1 May 1941 to form the Ministry of War Transport under Lord Leathers. The Minister of Shipping had lasted for 565 days.

A special mention has to go to Sir Tony Blair. After the Labour Party’s third general election win in a row in 2005, he decided, as so many prime ministers do, to rename the Department of Trade and Industry. The day after the election, Friday 6 May, he appointed Alan Johnson, MP for Kingston-upon-Hull West and Hessle and Work and Pensions Secretary since the previous year, as Secretary of State for Productivity, Energy and Industry. This was felt to be a more modern, dynamic and descriptive summation of the department’s role. Johnson was uneasy, and eventually pointed out that “Productivity, Energy and Industry Secretary” could (and most certainly would) be represented by the acronym “PENIS”, which was if nothing else an open goal for satirists. A week later, on 13 May, it was agreed that he would remain Trade and Industry Secretary, though he would be the second from last. When Gordon Brown became Prime Minister on June 2007, the ministry was divided into the Departments for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform, and Innovation, Universities and Skills.

At the other end of the scale, to show the deep British ambivalence towards institutional innovation, the current cabinet contains a Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, whose office dates back to at least 1283, a Lord Chancellor, Shabana Mahmood, who can trace her role to William the Conqueror’s Chancellor, Herfast, in 1068, and perhaps as far as Angmendus in AD 605, and a Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, Baroness Smith of Basildon, whose first predecessor, William Melton, was appointed in 1307. The Lord President of the Council, Lucy Powell, holds an office created in 1529, while the Prime Minister, Sir Keir Starmer, is also First Lord of the Treasury: this makes him the most senior member of a commission to exercise the office of Treasurer of the Exchequer which appears around 1126.

The cabinet also contains 17 secretaries of state (formally His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for…), which is now the standard British designation for the ministerial head of a government department. Apart from the Cabinet Office, the last mainstream department not to be headed by a secretary of state was the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF), which was subsumed into the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs after the 2001 general election. MAFF was headed by the Minister of Agriculture &c., and it was only during the Labour government of 1964-70 that secretaries of state began to predominate. However, all secretaries of state are manifestations of an indivisible whole, of one office of Secretary of State, and in most cases can legal undertake the duties of any other secretary of state. The role began as the King’s Clerk or Secretary, the first identifiable holder of which is John Maunsell in 1253, originally responsible for the monarch’s correspondence but also sometimes acting as an adviser. Robert Braybrooke, Secretary to Richard II from 1377 to 1381, also controlled the King’s signet ring, with which official documents could be authorised. In the early Tudor period, the King’s Secretary became the Principal Secretary and then the Secretary of State, and from 1540 there were usually two Secretaries of State, the first pairing being Sir Thomas Wriothesley (1540-44) and Sir Ralph Sadler (1540-43). At the Restoration, the office was more formally divided between the Secretary of State for the Northern Department—responsible for relations with Russia, Sweden, Denmark-Norway, Poland, the Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire—and the Secretary of State for the Southern Department—relations with France, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, the Italian states and the Ottoman Empire as well as the governance of Ireland and colonial issues. Domestic responsibilities were shared between the two departments. These would become the Foreign and Home Secretaries in 1782.

A bonus: although the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food was effectively wound up when DEFRA was created in June 2001, it was not formally abolished until the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (Dissolution) Order 2002 came into force of 27 March 2002. For the intervening nine months, Margaret Beckett was described as Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, but in statutory terms she was also Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food until the order came into force.

“Journalism can never be silent: that is its greatest virtue and its greatest fault.” (Henry Grunwald)

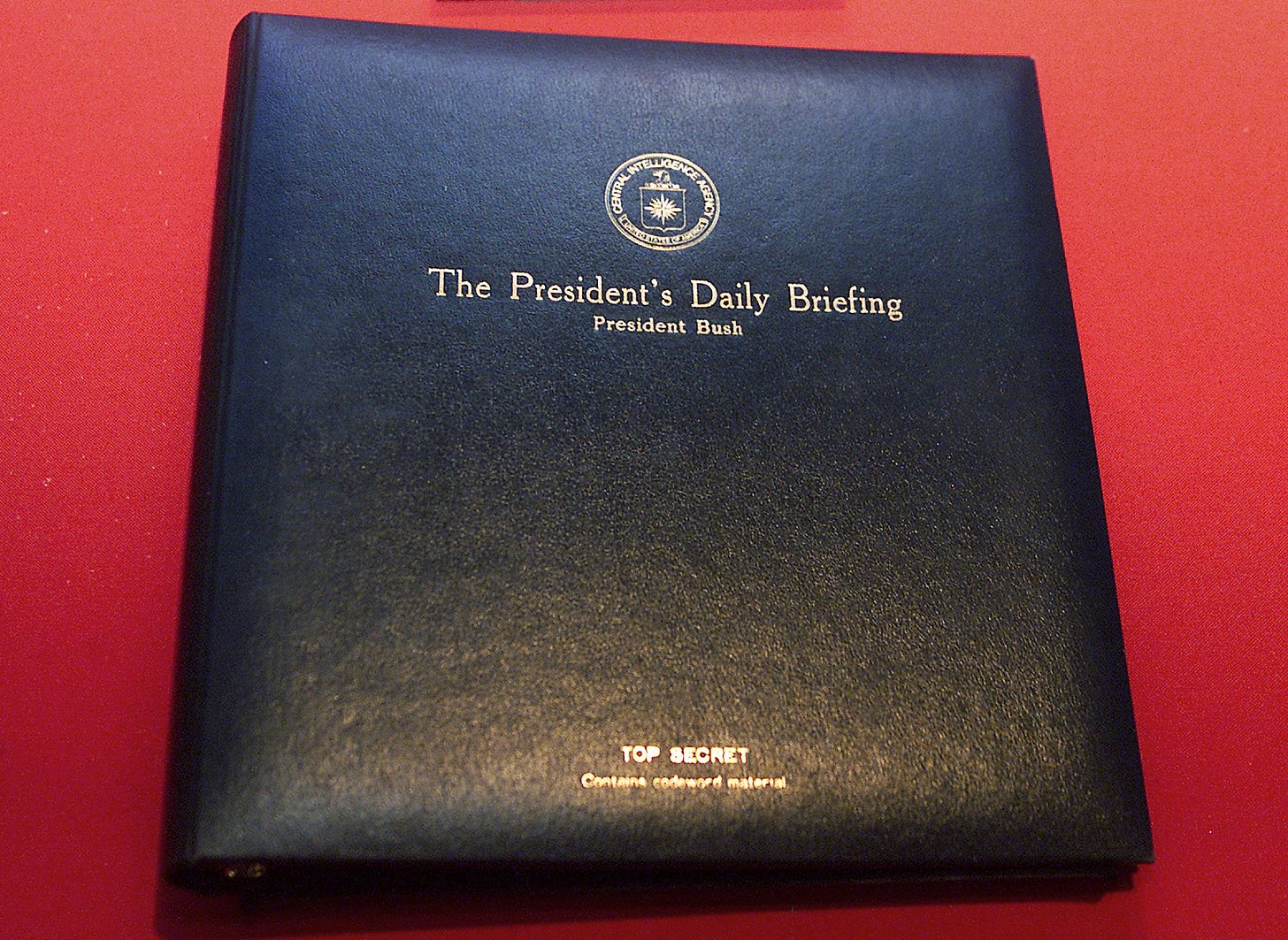

“The US President’s daily dose of intelligence”: the President of the United States is given a digest of intelligence at the beginning of every working day. Its contents are highly classified, highly restricted and allow the Intelligence Community, 18 separate organisations, an extraordinary and privileged open channel to the Commander-in-Chief. It has been part of the President’s routine since December 1964, although its style and content are tailored to suit individual incumbents. In Engelsberg Ideas, former CIA analyst David Priess traces the development of the President’s Daily Brief (PDB) and shows how it works best and has most influence when it meets the needs of each president rather than being imposed on them. President George H.W. Bush, the only former CIA chief to make it to the Oval Office, took particular interest in the PDB and demanded that its circulation be very restricted. Given what we know of President Trump’s carelessness, instinctive pushback against authority and disinclination to read or absorb continuous prose, one wonders how the agencies (of which he is deeply suspicious anyway) are managing to provide him with the information he needs.

“Is Pete Buttigieg the Democrats’ saviour?”: Katy Balls, having recently left The Spectator to become Washington Editor of The Times, looks at the ambitions and manoeuvring of former Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, as leading Democrats feel their way into the second Trump era and position themselves within their own party. I have to say that, based on my own observations of American politics, I think Buttigieg has little chance of emerging as the Democratic candidate for the presidency in 2028, and, if he did, would be soundly beaten. He is a perfect illustration of the commentator’s (very agreeable) delusion that the public would be enthralled by a serious-minded, wonkish candidate who talked in depth about policy, if only such a candidate emerged. I think it’s rarely (though not never) true, and I certainly see nothing in current politics to suggest that it would appeal to the US electorate. One strategist remarks: “He’s easy to make fun of, but he is memorable—and he’s very different to what the Republicans are offering.” That may be so, but different is not automatically better. Buttigieg is undoubtedly clever and articulate (he speaks seven languages), and he served in naval intelligence after working for McKinsey and Company. But when he sought his party’s nomination in 2020, he barely registered with black and Latino voters, while his polite centrism wasn’t enough for radical younger voters. In addition he served in President Biden’s cabinet for four years and can therefore be attached to every misstep or stumble of that administration. If Democrats think this the candidate profile they need to win in four years time, they have a lot of learning still to do.

“Abigail Spanberger Says She Can Take on Trump Without Bashing Him”: Vanity Fair contributing editor Chris Smith looks at another Democratic hopeful, Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA officer and US Representative for Virginia who is now her party’s candidate for Governor of Virginia in November. Her approach is pragmatism and a focus on the everyday concerns of voters, and she has tried not to become fixated with condemning President Trump’s every action and allowing him to set the pace. “If you’re working 80 hours a week to pay the rent and put food on the table,” Spanberger says, “and, oh my God, hopefully your kid doesn’t get sick—they [voters] don’t want to be excited. They want somebody to fix it.” Current polls give her leads ranging from narrow to generous over her Republican opponent, Lieutenant-Governor Winsome Earle-Sears, in a state which has voted narrowly for the Democratic candidate in the past five presidential elections, but went Republican in 13 of the 14 contests before that. If Spanberger becomes Governor it will give her a powerful platform running the 12th largest state in the Union: but, as with Pete Buttigieg, is quiet, pragmatic, moderate empathy going to be enough to overcome MAGA?

“Trump only sees the world through deals”: in The New York Times, conservative columnist Ross Douthat examines Donald Trump’s often-proclaimed love for deal-making and argues that in one sense it gives him a radical flexibility denied to most politicians because he is so firmly focused on achieving an outcome. This apparent pragmatism has won his popularity with the electorate, although, as the negotiations over the war in Ukraine are revealing, Trump will often seem to accept a bad deal without always realising he is being manipulated (as he has comprehensively been by President Vladimir Putin). As Douthat sums up the problem of this transactionality, “The problem with making deals your North Star is that it can be hard to distinguish between good ones and bad ones”.

“We can only sleep safe at night because rough men stand ready to do violence on our behalf”: former British Army officer Hamish de Bretton-Gordon addresses current accusations of atrocities against members of UK Special Forces in Afghanistan and, without condoning or excusing any criminality which may be proven, issues a necessary corrective for The Daily Telegraph. Special Forces—principally the Special Air Service (SAS), the Special Boat Service (SBS) and the Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR)—undertake some of the most dangerous and vital military operations in which UK forces engage. They are world-renowned, highly skilled and can exercise influence far beyond their size. What they do is not always pretty, because war is not pretty, but they are expected to abide by the same rules as all combatants. De Bretton-Gordon feels they are being subjected to unfair and distorted scrutiny, and warns of the long-term damage this could do.

“Without optimism, we won’t reach our next golden age”: in CapX, the journal of the Centre for Policy Studies, Johan Norberg, a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, puts forth an argument with which I have a great deal of sympathy and which I have advanced in relation to the Conservative Party, that real political and societal progress must be underpinned by a sense of optimism and self-belief. He acknowledges the challenges currently facing the West but also highlights the advantages we have and how they can be exploited if we don’t limit ourselves through our own anxiety. “You need a sense that there is hope and possibility, and you need role models around you who have shown the way, to make it seem like it is worth trying. Others to be inspired by, learn from, and to compete with.” We are a remarkable species and we have done remarkable things. Pollyanna-ism won’t make us safe or prosperous, but some self-belief will open our eyes to how much we can achieve.

“How emotions shape our decision-making”: in his regular “The Wiki Man” column in The Spectator, the reliably brilliant Rory Sutherland explains that, whatever we like to tell ourselves, human decision-making is rarely a logical and linear process, but rather a haphazard, lurching, emotional series of twists and turns. It is when we have reached a decision that we then look back and attempt to impose on it a purely retrospective rationale—but this is often a good thing, as it is the quirkiness and irrationality which allows us to innovate and expand our world unexpectedly. Bureaucracies, Rory suggests, with their low appetite for risk and a quantification bias, restrict us to solutions which have already been attempted and prevent is from trying anything radical or revolution, but it’s there that major progress lies.

“I’m now disabled—it’s made me more determined to work than ever”: writers don’t come much more divisive in terms of their reception than Julie Burchill, who has been crafting the written word as a profession for nearly 50 years now since she burst on to the scene at New Musical Express as a 17-year-old. She is a provocatrice who revels in giving offence, and I doubt if anyone agrees with everything she says, but I always find her interesting to read for the very reason of her provocation, and I also think she’s a very skilled wordsmith who knows exactly what she’s doing. Recently she underwent surgery for a spinal abscess which has left her unable to walk, but she seems astonishingly free of self-pity (though she would be forgiven for wallowing in it). In this article for The i Paper, she describes the way in which losing her mobility has deepened her determination to continue doing what she feels defines her, which is writing. “I plan to keep working—and paying tax—until I drop down dead, something many thousands of able-bodied people certainly can’t say.” I wouldn’t dare bet against her.

“After Losing 1,000 Tanks, Ukraine Is Rethinking How It Uses The Heavily Armed Vehicles”: in Forbes, of all places, military correspondent David Axe examines the war in Ukraine and the lessons it offers for future conflicts. The biggest single innovation, I think, has been the ubiquity of drones of all shapes, sizes and functions. I can remember visiting Iraq in 2008, not so every long ago, where the Royal Air Force had just begun to operate their first MQ-9A Reaper drones and they seemed both to me and to the airmen eerily futuristic, divorced from the essential human element of war. Axe describes how the potency and reach of drones on the battlefields of Ukraine have profoundly affected the way that armoured vehicles, especially tanks, are now used. Because they are so vulnerable to attack from above and represent such an uneven cost comparison (a €30 million Leopard 2 main battle tank could be immobilised or destroyed by a kamikaze drone costing a few thousand dollars), armoured vehicles often now have to seek cover and emerge only briefly to use their main weapons, which can still be game-changers in a tactical situation. Ukrainian soldiers, getting to grips with their M1A1 Abrams, their Leopard 2s and their Challenger 2s, will tell you that the tank is not dead, a conclusion to which some rushed; but its place on the battlefield is undergoing radical change.

“Barbara’s Backlash”: Marjorie Williams was a gifted and respected writer on politics for Vanity Fair and The Washington Post who died of cancer in 2005, aged only 47. In August 1992, she wrote this fascinating Vanity Fair profile of First Lady Barbara Bush as her husband, President George H.W. Bush, fought for re-election that November (he would lose by a surprising margin to little-known Democratic Governor of Arkansas Bill Clinton after other party grandees avoided the nomination in expectation of defeat). Because he succeeded the famously elderly Ronald Reagan, and because of his own deceptively youthful vigour, it is easy to forget how old Bush was; when this was written, he had recently turned 68, and Barbara had been 67 four days previously. The First Lady’s public image was of a no-nonsense, hard-headed but affectionate grandmother, but as Williams unpicked, the reality was much more complex and interesting than that. A fine example of thorough, perceptive but engaging political journalism.

From the archives: F.E. Smith’s maiden speech (1906)

As I warned, I am experimenting with the format of these weekly round-ups (rounds-up?) while the television and film recommendations are being “rested”. This element suggested itself to me for purely personal reasons: writing about public affairs and public life as I do, with the bias of historical training and inclination, I often refer to, cite or draw on famous speeches, articles, editorials and so on, sometimes realising that I have forgotten or overlooked parts of them, have never read them properly or in full or, most alarmingly, think I’ve read them but haven’t. It may be that literally no-one else on the planet suffers from this problem, but it’s my blog and I’ll quote if I want to, so for the next few weeks, at least, I will present and frame briefly some important works.

I’ll try to avoid the most obvious—the Sermon on the Mount, Churchill in 1940, the “Choose Life” monologue from Trainspotting—without being deliberately obscurantist. And I want to make it very clear that this could not be further from a dismissive “Oh my God, I can’t believe you’ve never read this seminal pamphlet on crop rotation from the 1770s!” It’s as much a reminder and discipline for me as it is (hopefully) interesting and informative for you. Let’s see how we get on. Nothing, as I am forever citing Peter O’Toole as T.E. Lawrence saying, is written.

“I warn the government…”

One of my great political heroes, or at least inspirations, is F.E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, the brilliant, dynamic, witty, savage and ultimately self-destructive Tory lawyer who blazed his way through the first third of the 20th century, held high office at a relatively young age, had a razor-sharp but restless intellect and enjoyed a lifestyle that killed him at 58. F.E. was perhaps the greatest orator the Conservatives (or Unionists, as they were known for shorthand for most of his career) possessed, perhaps the match of his great friend and sometime rival Winston Churchill. He had an advantage over Churchill of a ruthlessly incisive and forensic mind who predisposed him towards a career at the Bar and honed itself further in practice; at the same time, he lacked Churchill’s grand visionary sweep, and towards the end of his life he was becoming more pompous, his opinions ossified, his thoughts become sclerotic.

For those who are interested, the best single work remains John Campbell’s weighty 1983 biography, F.E. Smith: First Earl of Birkenhead. F.E.’s son, the 2nd Earl of Birkenhead, wrote a study of his father in 1933, revising it heavily in 1960, and it is diligent but, inevitably, partial and uncritical. He can otherwise be traced in the biographies of others, like Churchill, H.H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Bonar Law and Lord Curzon. But F.E. is at his best, his most brilliant, funny and excoriating, in his speeches, because it was in oratory that his true gift lay and perhaps where he was most comfortable.

Anyone interested in political speeches and particularly in parliamentary speeches should read F.E.’s maiden speech for which I provide a link below. To give some context, at the end of 1905, the Unionist Prime Minister, A.J. Balfour, resigned not just his own office but the place of his government. The coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Unionists which had been in power since 1895, and, with a short Liberal interlude in 1892-95, since 1886 was exhausted and increasingly divided between supporters of free trade and exponents of “tariff reform”, a tax on imports which would favour goods from the rest of the British Empire.

Although the coalition had won a substantial majority of 134 at the general election in 1900, Balfour was losing authority rapidly. By resigning his whole government, he hoped that King Edward VII would invite the Liberal leader, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, to form an administration (which he did), and that the government which resulted would be weak and ineffective, discrediting the Liberals. It did not work. Campbell-Bannerman decided to ask for an immediate dissolution of Parliament, which took place on 8 January 1906, and the ensuing general election saw the Liberals more than double their tally of seats to 397, giving the Prime Minister a majority of 125. The Unionists held only 156 seats, and Balfour himself was defeated in Manchester East. It was the worst parliamentary result for the Conservatives since their foundation in 1834, and would remain so until last year. In addition, the Irish Parliamentary Party won 82 seats, the Labour Representative Committee saw 29 MPs elected and half a dozen independents of various stripes completed the House.

There were 34 newly elected Unionist MPs, of whom one was the 33-year-old barrister Frederick Edwin Smith, Member of Parliament for Liverpool Walton. He was already a well-known and high-earning advocate on the Northern Circuit, based in Liverpool, and he had scraped into Parliament by 709 votes ahead of his Liberal opponent by posing as the champion of the hard-drinking, patriotic working-class man (of which qualities he certainly shared two). On 12 March 1906, he made his maiden speech.

It was well into the evening and the House of Commons was debating a shamelessly partisan motion by the Liberal MP for Colne Valley, Sir James Kitson, was purely sought to celebrate the government’s recent election victory and attempt to exacerbate the divisions within the Unionist coalition between free traders and tariff reformers. Kitson had proposed:

That this House, recognising that in the recent General Election the people of the United Kingdom have demonstrated their unqualified fidelity to the principles and practice of Free Trade, deems it right to record its determination to resist any proposal, whether by way of taxation upon foreign corn or of the creation of a general tariff upon foreign goods, to create in this country a system of protection.

Balfour, who had only returned to the House a fortnight before at a by-election in the City of London after his defeat in Manchester, had spoken before the debate had been adjourned for dinner, and Campbell-Bannerman had been on the Treasury bench; the godfather of tariff reform, Joseph Chamberlain (Birmingham West), and his eldest son, former Chancellor of the Exchequer Austen Chamberlain (Worcestershire West), had also spoken. F.E. followed the new Labour MP for Wakefield, Philip Snowden (later Labour’s first Chancellor of the Exchequer 1924 amd 1929-31).

Public speaking of course held no terror for F.E. The tone he adopted was inspired: certainly, he admitted, there were differences of opinion within his own party—he was a supporter of tariff reform—but he did not think that was what had cost them the general election, and anyway the Liberal Party was not absolutely united on the matter either. He took aim squarely at Lloyd George, the President of the Board of Trade, and at his future close companion Churchill, who had defected from the Conservatives to the Liberals in 1904 and had been appointed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies (the Secretary of State, the Earl of Elgin, was in the House of Lords). Again and again he skewered promises Liberal MPs had made or accusations they had levelled, and exposed them as falsehoods and smears.

His most telling blow, however, all the more powerful because he had not sought to play down his party’s defeat or diminish the Liberals’ achievement, was when he reminded Members opposite that minorities had rights, that a majority should not be high-handed and that political success was only ever temporary. His peroration was stinging.

I know that I am the insignificant representative of an insignificant numerical minority in this House, but I venture to warn the Government that the people of this country will neither forget nor forgive a party which, in the heyday of its triumph, denies to the infant Parliament of the Empire one jot or tittle of that ancient liberty of speech, which our predecessors in this House vindicated for themselves at the point of the sword.

The speech was regarded as a triumph and established F.E.’s reputation instantly. Tim Healy, the Irish Nationalist MP for North Louth who was a powerful and punchy speaker himself, afterwards sent F.E. a note, which said “I am old, and you are young, but you have beaten me at my own game”. The historian Paul Johnson supposedly described it as “without question the most famous maiden speech in history, quite unprecedented, and never equalled since”.

The speech is recorded in the Official Report of the House of Commons, better known as Hansard. However, the parliamentary records of the time translated contributions into reported speech, so it loses much of its power and immediacy. That said, it allows the speech to be read in the context of the rest of the debate, so it is a useful resource and can be found here. F.E. made such an impact, however, that journalists paid close attention and his words were preserved in full and as close to verbatim as is possible. The speech was reproduced in The Times the following day, but a full transcript can be found here. It is a dazzling display of Edwardian parliamentary rhetoric, and it is not hard to imagine the sensation it created.

It’s hard to say goodbye to the streets…

… as Snoop Dogg once remarked. It’s all how you do it. You can pass by and say, “What's happening?” and keep it moving, but it’s a certain element that’ll never be able to roll with you once you get to this level, because that’s the separation of it all. Truly one of the profound thinkers of our age. Our separation, dear readers, is only temporary. Until next time.

You neglected to mention his sobriquet "Galloper Smith" - a King's Counsel who promoted subversion of a lawfully enacted Act of Parliament!

Something insignificant and yet deeply substantial about this round up; your almost irreverence for the present more than rounded out by insights from a selective past.