An experiment in republican government: the Commonwealth of England established

Today in 1649 Parliament passed an act which made England legally a Commonwealth and Free-State without a monarch, but the constitutional settlement would not endure

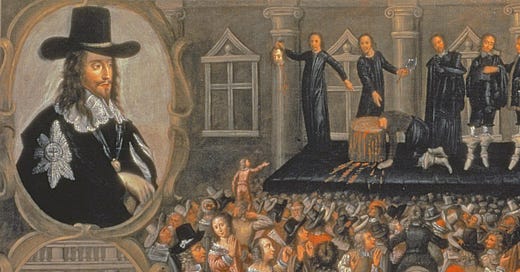

The execution of King Charles I on 30 January 1649 came after his conviction for treason by “an High Court of Justice” created by the House of Commons only three weeks before. In strict legal terms the whole process was a nonsense: the so-called “act” of January establishing the court had not been agreed to by the House of Lords or granted Royal Assent so was no act at all, but rather an ordinance issued by the Commons alone yet claiming full statutory authority; and it was not at all clear in any event that Parliament had any jurisdiction to sit in judgement on the monarch, a point Charles made forcefully but in vain at the beginning of his trial:

I would know by what power I am called hither. I would know by what authority, I mean lawful; there are many unlawful authorities in the world… Remember, I am your King, your lawful King… Let me see a legal authority warranted by the Word of God, the Scriptures, or warranted by the constitutions of the Kingdom, and I will answer.

As early as March 1642, when Charles had refused Royal Assent to the Ordinance for the Militia, the Commons and Lords had declared that “in this Case of extreme Danger, and of His Majesty’s Refusal”, legislation could be passed without Royal Assent. This was taken a step further in 1649 when the Commons determined that it could make law without the House of Lords or the King.

In practical terms, there had never been any chance of the King being acquitted. The Prince of Wales, Prince Charles, was in The Hague at the court of his brother-in-law, William II, Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, who had married Charles I’s daughter Mary. In legal theory, the moment the axe fell on his father’s neck in Whitehall, he became King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland (the English monarchy maintained its claim to the French throne from 1340 to 1801); and on 5 February, the Parliament of Scotland proclaimed Charles “King of Great Britain, France and Ireland” but would only allow him to enter Scotland if he agreed to establish Presbyterianism as the official religion throughout England, Scotland and Ireland. This he would not do.

In reality, Charles II was a king in exile, and would only assume his throne with practical effect in 1660. In the hours before his father’s execution, the House of Commons hurriedly passed the Act prohibiting the proclaiming any person to be King England or Ireland, or the Dominions thereof, which prohibited Charles II’s succession. On 6 February, it resolved that the House of Lords was “useless and dangerous and ought to be abolished”, and the next day, now styling itself “the Parliament of England”, it resolved that:

the office of a king in this nation, and to have the power thereof in any single person, is unnecessary, burdensome, and dangerous to the liberty, safety and public interests of the people of this nation, and therefore ought to be abolished.

On 13 February, “Parliament” issued an ordinance establishing the Council of State which superseded the Privy Council as the chief decision-making body. The resolutions were transformed into acts, with the Act for abolishing the Kingly Office passed on 17 March and the Act for abolishing the House of Peers following two days later.

On 22 March, Parliament published a declaration which justified its “late proceedings”, from the trial and execution of Charles I to the abolition of the House of Lords. It stressed its identity as “the Representatives of the People now Assembled in Parliament”, and referred variously to England as “this Commonwealth” and “a Republique”. It concluded by expecting:

from all true-hearted Englishmen… a chearful Concurrence and acting for the Establishment of the great Work now in Hand, in such a Way, that the Name of God may be honoured, the true Protestant Religion advanced, and the People of this Land enjoy the Blessings of Peace, Freedom, and Justice to them and their Posterities.

All of this, it should be remembered, was done by a House of Commons which had been summoned in September 1640, and in May 1641 the King had been forced to agree to an act which forfeited his power to dissolve Parliament. What became known as the Long Parliament (as it would not formally be dissolved until 1660, in its 20th year) also saw those Members who opposed the plan to put the King on trial removed in November 1648 in Pride’s Purge, when Colonel Thomas Pride and two regiments of the New Model Army prevented them from entering the House of Commons and in some cases imprisoning them. The loyalist body of around 210 MPs which remained was then dubbed the Rump Parliament, and would itself be disbanded by Oliver Cromwell in April 1653.

In those first months of 1649, there is a strong sense of the Parliamentarian leadership improvising and acting spontaneously, devising a constitutional settlement as it went along. The presidency of the Council of State was initially assumed pro tempore by Cromwell, at that point MP for Cambridge and a senior officer in the New Model Army, before John Bradshaw became Lord President in March 1649, a role he would hold for two-and-a-half years. A barrister, serjeant-at-law and judge from Cheshire, he had been Lord President of the High Court of Justice which had tried the King, and went on to oversee the trials of and death sentences passed on a number of leading Royalists including the Duke of Hamilton, Lord Capell of Hadham, the Earl of Holland and Eusebius Andrews. Initially there were 41 people nominated to the Council of State, though its first meeting in February 1649 saw only 14 attend, not far above the legal quorum of nine.

Finally, on 19 May, Parliament passed the Act Declaring and Constituting the People of England to be a Commonwealth and Free-State. This extraordinarily short statute of just 103 words stated that the Commonwealth would be governed “by the Supreme Authority of this Nation”, with power exercised by “the Representatives of the People in Parliament, and by such as they shall appoint and constitute as Officers and Ministers under them for the good of the People, and that without any King or House of Lords”. It was in some ways a concise reiteration and underlining of the measures introduced over the preceding months, placing absolute authority in the hands of the Rump Parliament, those 200 or so Members who had not been displaced by the army.

The Commonwealth of England in its initial form did not last long: within four years of the act being passed, the Rump Parliament had been forcibly sent away and the Council of State put into abeyance. It had not proved a successful or effective form of government, and for all its grand rhetoric of “the People of England” and their supreme authority, it is hard to see that it was very much more representative or less autocratic than the system it replaced. It was true that it had no single powerful ruler, at least in institutional terms, but it effectively empowered the most influential members of a much-reduced House of Commons which had been elected a decade before and which could only be dissolved by its own authority.

After the Rump Parliament was disbanded, the Council of Officers, the ruling body of the New Model Army, adopted the Instrument of Government, which declared that supreme legislative authority “shall be and reside in one person, and the people assembled in Parliament; the style of which person shall be the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland”. The new Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, now generally referred to as the Protectorate, concentrated enormous power, “the chief magistracy and the administration of government”, in the hands of the Lord Protector, with few checks or balances. That Lord Protector, of course, was Oliver Cromwell.

Britain’s experiment with republicanism was short-lived. Cromwell was offered the crown by Parliament in 1657 but eventually declined after much agonising, but was then reinstalled as Lord Protector in a quasi-regal ceremony and with more extensive powers than before under the Humble Petition and Advice. In September 1658, he died at the age of 59, probably as a result of sepsis following a kidney or urinary disorder (it was brought on by an attack of malarial fever, and it is though he may have rejected quinine, the only effective treatment at that time, because it had been discovered by Catholic missionaries). His 31-year-old son Richard succeeded him as Lord Protector but, lacking a power base in the army, was unable to exercise any real authority and resigned within nine months.

In May 1660, Charles II returned from exile on the Continent to assume in reality the throne which by inheritance had been his since January 1649 and the Stuart dynasty was restored. Today, 365 years after the Restoration, with the sixteenth monarch since Charles II (and his namesake) on the throne, republicanism remains, to judge by most opinion polls, a minority pursuit.

Right up my street!!

Really interesting piece, so thanks for writing Eliot. I always find it interesting how regal our attempt at a republic actually was.

Cromwell's title "by the Grace of God of the Republic of England, Scotland and Ireland etc. Protector" and, as I understand, he was still referred to as "His Highness".