Sunday round-up 11 May 2025

The anniversary of the only assassination of a prime minister, birthdays for Eric Burdon and Jeremy Paxman, and 15 years since the Cameron/Clegg coalition was formed

One or two pieces of housekeeping: there are no television recommendations this week, because, once again, I simply haven’t had time to watch much television so there seems no point peddling inauthentic recommendations. Secondly, to my astonishment, gratitude and genuine humility, the subscribers of this blog are edging gradually towards 1,000. We are not a revolution yet but every movement starts somewhere and Christ only had 12 followers. Do pass it on to those who you think would find it interesting—in an ever-more commodified world, word of mouth has a power all of its own, and I’m just vain enough to want more readers. It’s still free.

Celebrating in their own (very different) ways today are usually mononymous fashion designer Valentino Garavani (93), black nationalist and probably-misunderstood-antisemite Louis Farrakhan (92), singer-songwriter and Geordie blues legend Eric Burdon (84), former Conservative MP and MEP Nirj Deva (77), stalwart actress Pam Ferris (77), journalist, broadcaster and grand inquisitor Jeremy Paxman (75), Leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and former journalist Mike Nesbitt (68), model and actress Laetitia Casta (47), actress, singer, model and Nigel Farage’s “close personal friend” Holly Valance (42) and singer and actress Sabrina Carpenter (26).

Our ghostly celebrants on the other side include former Vice-President of the United States Charles W. Fairbanks (1852), legendary composer, songwriter and pianist Irving Berlin (1888), surrealist painter and war artist Paul Nash (1889), difficult-to-categorise Salvador Dalí (1904). actor and comedian Phil Silvers (1911), theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman (1918), actress and dynast Natasha Richardson (1963), terrorist and final pilot of United Airlines Flight 93 Ziad Jarrah (1975) and actor and singer Cory Monteith (1982).

Setting the standard

Today in AD 973, Edgar, great-grandson of Alfred the Great, was crowned King of the English (rex Anglorum) at Bath Abbey. The title is first recorded as having been used in AD 928 by Æthelstan, Edgar’s uncle, and Edgar was the fifth monarch to bear it, after his father, another uncle and his elder brother, Eadwig.

Edgar and Eadwig’s uncle Eadred died in November AD 955. Eadwig, aged 14 or 15, became King of the English and was crowned at Kingston-upon-Thames in a relatively simple ceremony in January AD 956 followed by a celebratory feast; it is alleged that the King absented himself towards the end of the meal to enjoy a threesome with a mother and her daughter. Eadwig seems to have been both a poor ruler and an unpleasant man, but at any rate by AD 957 he was sufficiently unpopular in the north of his realm that it was divided along the River Thames, and Edgar became ruler in the north while Eadwig remained in the south. That said, political unity was not prized above all else, and kingship was often shared. Edgar thereafter tended to be styled King of the Mercians, and occasionally of the Northumbrians and Britons. The coinage retained Eadwig’s name, which suggests the division was not wholly unplanned or unwelcome, and Eadwig was clearly the senior.

However, in October AD 959, Eadwig died, aged 18 or 19. The circumstances are unknown, with suggestions ranging from an inherited ailment or disease to a convenient “accident”. Edgar now became King of the English at the age of 15 or 16, but he seems not to have held a coronation immediately, or, if he did, no record of it has survived. It would be almost 14 years until the ceremony at Bath, which would set the template for English coronations and include some elements still in use today.

The King had recently sent an embassy to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I (who would die just four days before Edgar was crowned). The German court was considered the most advanced and sophisticated in western Europe in terms of ceremony and protocol, and it may be that the ambassadors brought back inspiration for the coronation. However, most of the planning was undertaken by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dunstan, a Benedictine monk in his 60s who was one of the King’s closest advisers.

Bath Abbey was already nearly 300 years old at this stage, and the monastic church had been rebuilt in the 8th century by King Offa of Mercia. Edgar was an enthusiastic patron on monasticism and promoted the use of the Rule of St Benedict, making Bath a natural choice for his great ceremony. The most striking fact about the coronation was the degree of identification of the king as a priestly figure, wearing vestments like a cleric’s and promising to protect the Church. Edgar was presented to the congregation by Archbishop Dunstan to be recognised, with the cheers of “God save the King!”, and Edgar took the following coronation oath:

In the name of the Holy Trinity. I promise three things to the Christian people subject to me:

Firstly, that God’s church and all the Christian people of my dominions will be held in true peace;

Secondly, I forbid robbery and all unlawful deeds by all ranks of men;

Thirdly, I promise and command justice and mercy in all judgments, in order that the gracious and merciful lord, who liveth and reigneth, may thereby forgive us all through his everlasting mercy.

Dunstan anointed Edgar with chrism, or holy oil, to indicated the consecrated nature of his kingship, then placed the crown on his head as he sat in the coronation chair. Dunstan and others then paid homage to the King. In addition, Edgar’s wife, Ælfthryth, was crowned and anointed as Queen in the same ceremony.

These rites still take place, and took place at the coronation of King Charles III two years ago. The King swore an oath, was anointed and crowned, the Queen anointed and crowned with him, and his subjects them paid homage to him. St Dunstan would surely be pleased at the enduring nature of his creation.

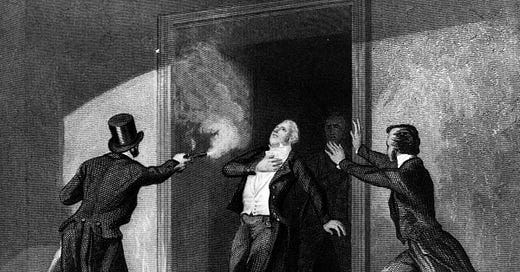

He’s got a gun!

At 4.30 pm on this day in 1812, the House of Commons resolved itself into a Committee of the whole House in order to hear petitions against several Orders in Council which had been issued in 1807, extending the blockade which the British government had imposed on France and its allies during the Napoleonic Wars. When Russia had signed the Treaty of Tilsit with France in July that year, Russian ports automatically came under the provisions of the blockade. In general because of the strength of the Royal Navy, the blockade had been effective, severely limiting France’s trade while the United Kingdom remained able to import and export to the rest of the world. But inevitably some merchants and men of commerce had suffered, and some had petitioned the House against the Orders.

Henry Brougham, a Scotsman sitting as the Whig Member of Parliament for Camelford in Cornwall, had spoken against the Orders earlier in the year. As the Committee of the whole House began, he noted the absence of the Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval; the latter also held the office, as prime ministers in the House of Commons did at the time, of Chancellor of the Exchequer, and, moreover, he had been Chancellor since 1807, when some of the Orders had been issued. Brougham, however, scotched any suggestion that the House wait for the Prime Minister to arrive and insisted that proceedings move on. A messenger set off for Downing Street to alert Perceval to what was going on.

In fact, by that time, Perceval was already on his way. He had decided to walk the short distance from Downing Street rather than take a carriage—almost an impossible choice for prime ministers now for security reasons—but on Parliament Street had encountered his friend James Stephen, the MP for Tralee; he was a barrister who had spent several years in the Caribbean and had become a passionate advocate of the abolition of slavery, but he was also an experienced trade lawyer and had drafted the Orders in Council now being examined. When the Prime Minister heard the messenger’s summons, he set off in haste to the House of Commons.

Perceval reached Westminster Hall, the great mediaeval chamber built by William II in the 1090s, at 5.15 pm. In the old Palace of Westminster, the hall served as the home of three of the most important organs of the judiciary, the Court of King’s Bench, the Court of Common Pleas and the Court of Chancery. It also served as a lobby for both Houses; the House of Lords had in 1801 moved from the Painted Chamber into the larger White Chamber, just south of Westminster Hall, while the House of Commons had since 1547 met in St Stephen’s Chapel, at right angles to the hall. This was, by definition, open to the public, since Westminster Hall was not only a judicial space but also allowed people to meet their Members of Parliament and “lobby” them.

John Bellingham had been in and around Westminster Hall since mid-afternoon. He was in his early 40s, and had endured a number of unsuccessful attempts at a career: at 16 he had become a sailor and served on a ship owned by the East India Company; he had worked as a clerk in a counting house; and around 1800 he had travelled to Arkhangelsk in northern Russia as an agent for importers and exporters. In 1804, about to return to Britain, he had been imprisoned in Russia for his supposed liability of 4,890 roubles as part of a bankruptcy. He secured his release after a year and went to St Petersburg in fury to seek the impeachment of the Governor of Arkhangelsk who had allowed his imprisonment, only for the imperial authorities to charge him with leaving Arkhangelsk without permission and put him back in prison. At length, he once again managed to negotiate his release and finally returned to Britain in December 1809.

He was now a man with a grievance, and petitioned the government for compensation for his imprisonment, accusing the ambassador to Russia, Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, of failing to protect a British subject. He wrote to the Foreign Secretary, the Privy Council and the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Perceval himself by this point) as well as petitioning the Prince Regent. The government’s stance was that it had ceased diplomatic relations with Russia the year before and therefore had no responsibility for what had happened to Bellingham, and for a while his wife persuaded him with some difficulty to let the matter lie. In 1811, however, he decided to resume his case. He approached his Member of Parliament in Liverpool, Lieutenant General Isaac Gascoyne, and Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, but found no satisfaction, so travelled to London in April 1812.

On 18 April, Bellingham met an official at HM Treasury, a Mr Hill, who reiterated that the government could not help him. Bellingham warned Hill that he would be forced to “take justice into his own hands”, to which Hill responded, unwisely as it would transpire, that he would have to “take measures such as he thought appropriate”. Two days later, Bellingham bought two pistols from W.A. Beckwith of Skinner Street.

That afternoon of 11 May, Bellingham was close to the door to the House of Commons. As Perceval approached to enter the chamber, Bellingham took one of the pistols from a concealed pocket he had had added to his overcoat, stepped forward and shot the Prime Minister in the chest at close range. Perceval staggered a few steps, gasping “I am murdered!”, then fell prone at the feet of William Smith, the radical MP for Norwich. Bellingham meanwhile sat calmly on a bench, still clutching the pistol, and when cries began of “Where is the murderer?”, he answered quietly “I am the unfortunate man”.

Smith initially thought the wounded man was William Wilberforce, the great slave trade abolitionist and Yorkshire MP, and it was only when Perceval was turned over that Smith recognised the Prime Minister’s face. A faint pulse was still present, and Smith and a friend carried Perceval to the office of the Speaker’s Secretary nearby where they laid him on a table, his feet propped on two chairs. A surgeon, William Lynn, had been summoned and arrived rapidly to examine the Prime Minister, by now unconscious, but the wound in his chest—Bellingham had shot him in the heart—was unsurvivable, and he died moments later, Smith supporting his head as he gave his last breaths.

There was such uproar in the lobby that Bellingham might easily have made his way out and escaped but he continued to sit quietly until an official identified him as the assassin and he was restrained. Gascoyne confirmed his name and Bellingham was searched, the second pistol found in his trouser pocket, then taken first to the Bar of the House of Commons and thence to the prison room in the Serjeant at Arms’s quarters for questioning. A number of MPs who were also magistrates were corralled under the chairmanship of Harvey Christian Combe, the Whig Member for the City of London and a former Lord Mayor, to conduct a committal hearing on the spot.

Bellingham could hardly have made it easier for them. He made no attempt to deny his action, and although he was clearly warned of the danger of self-incrimination, was frank with the magistrates.

I have been ill-treated… I have sought redress in vain. I am a most unfortunate man and feel here [he placed his hand on his heart] sufficient justification for what I have done.

He went on to explain all the avenues of redress he had explored and his singular lack of success, and that he had told the authorities he would be forced to seek justice on his own, only to be told he should do whatever he though appropriate. “I have obeyed them,” he added. “I have done my worst, and I rejoice in the deed.” Bellingham was formally charged with the murder of Spencer Perceval, and around 1.00 am he was transferred to Newgate Prison to await trial. An inquest was held into Perceval’s death that day, 12 May, in the less-than-salubrious surroundings of the Rose and Crown public house on Downing Street, and the coroner reported the cause of death as “wilful murder by John Bellingham”. On those grounds, the Attorney General, Sir Vicary Gibbs, urged the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, Lord Ellenborough, to arrange for a trial as quickly as possible.

Swiftness certainly followed. Bellingham’s trial began on 15 May at the Assize Court for London in the Old Bailey, which adjoined Newgate Prison. Sir James Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, presided and the Attorney General led for the prosecution. Bellingham entered a plea of not guilty, and his barrister, Henry Revell Reynolds, was unsuccessful in convincing the judge that Bellingham was insane (hardly helped by Bellingham agreeing that he had been quite in control of his actions, which he maintained were wholly justified). With seven hours, it was all done, and Mansfield advised the jury before they retired to consider their verdict, “The single question is whether at the time this act was committed, he possessed a sufficient degree of understanding to distinguish good from evil, right from wrong”. He reminded them that all the evidence showed Bellingham to be “in every respect a full and competent judge of all his actions”.

The jury returned within 15 minutes and delivered an inevitable guilty verdict. Bellingham seemed surprised but calm, and had nothing else to say when invited by the clerk of the court. Mansfield, describing the assassination of Perceval as being “as odious and abominable in the eyes of God as it is hateful and abhorrent to the feelings of man”, gave the only verdict he was ever likely to give in the circumstances:

You shall be hanged by the neck until you be dead, your body to be dissected and anatomised.

John Bellingham was hanged outside Newgate Prison on the stroke of 8.00 am the following Monday, 18 May, a week after he had killed Spencer Perceval. In accordance with his sentence, his body was sent to St Bartholomew’s Hospital for dissection, while his clothes were sold to the morbidly eager public. His skull is now in the Pathology Museum at Queen Mary University of London.

Spencer Perceval remains the only British Prime Minister to have been assassinated, if that is not too grand a word for his murder. Bellingham’s trial and sentencing have been much criticised by modern legal scholars, but it is hard to see what the Georgian judiciary could have done differently: he killed Perceval in public, with dozens of witnesses, not only admitted to it but explained his reasons and declared that he had done nothing wrong, he was convicted by a jury of his peers and he was sentenced to death for unquestionable guilt after a trial for a capital crime. This was at a time when there were more than 220 offences which carried the death penalty, from murder and high and petty treason to burglary and the forgery of stamps.

It would be an exaggeration to say Perceval is “famous”. If one begins with Sir Robert Walpole, as is conventional, there have been 58 prime ministers (55 men and three women) and Perceval is definitely in the lower half in terms of fame. He held the office for a little over two-and-a-half years, and it was an undistinguished period of continuing the war against France, maintaining the public finances and keeping a degree of public disorder under control with increasingly coercive measures. Had he not been assassinated, or were he one of several premiers to suffer that fate, he would languish in the same kind of obscurity as a number of fleeting Georgian chief ministers: the Earl of Shelburne (1782-83), the Duke of Portland (1783, 1807-09), William Grenville (1806-07). Perceval has two other claims to some kind of obscurantist fame: he is the only law officer to become Prime Minister, having served as Solicitor General (1801-02) and Attorney General (1802-06); and, until the appointment of Liz Truss in 2022, he was reckoned to have been the shortest Prime Minister, at 5’3” (he was nicknamed “Little P”). She is said to be the same height.

The rhythm of the saints

Today is the feast of St Anthimus of Rome (d AD 303), supposedly born in Bithynia and a priest in the reigns of Diocletian and Maximian, who destroyed a shrine to the god Silvanus and converted the priest of the shrine, for which he was thrown in the River Tiber with a millstone round his neck, miraculously rescued by an angel, recaptured and beheaded; of St Mamertus (d AD 475), from a wealthy Gallic family near Lyon, who became Bishop of Vienne and instituted days of Minor Rogation; of St Gangulphus of Burgundy (d AD 760), a nobleman and courtier to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks, who renounced his wealth and became a hermit but was murdered by a priest whom his wife had taken as a lover; and of St Majolus of Cluny (AD 906-AD 994), the fourth Abbot of the Benedictine monastery at Cluny, who undertook reform of many monastic houses, was close to the Emperors Otto I and II and continued his reforming work until his death in his late 80s.

Today is Somerset Day, marking the anniversary of the coronation of Edgar the Peaceful as King of the English in AD 973; the ceremony, the first of its kind, was conducted by Archbishop Dunstan of Canterbury in Bath Abbey, and Queen Ælfthryth, possibly Edgar’s third wife, was crowned in the same service (see above).

Readers in America (or indeed anywhere) can celebrate classic television science-fiction as today is National Twilight Zone Day, easily combined with Hostess CupCake Day. Though they should first make sure they properly mark Mother’s Day, celebrated today in the United States (Mothering Sunday in the United Kingdom was 30 March, we’re already done).

Factoids

A distant descendant of John Bellingham, the man who assassinated Prime Minister Spencer Perceval (see above), was the Member of Parliament for North West Norfolk from 1983 to 1997 and 2001 to 2019. Henry Bellingham (now Lord Bellingham) was a spokesman for the Opposition 2002-10 and a junior Foreign Office minister for Asia and the Pacific from 2010 to 2012. He announced his intention to stand for election as Speaker of the House of Commons in 2019 but withdrew before the process formally began.

(I am grateful to Dr Lucy Worsley for the following Austeniana, after attending a talk at the Adelphi Theatre this week.) We don’t really know with any accuracy what Jane Austen looked like. That may seem counter-intuitive, as the author has featured on Bank of England £10 notes since 2017, but the depiction on the banknote is a sanitised version based on two portraits, one a watercolour and the other an engraving, commissioned for A Memoir of Jane Austen (1869) by the author’s nephew, James Austen-Leigh. Those were both drawn loosely from a pencil and watercolour sketch by Austen’s sister Cassandra, made around 1810. It is the only depiction of Austen’s features drawn from life, and can be assumed to be reasonably accurate, but it has undergone quite a transformation from a Georgian sketch to today’s polymer banknote.

The first mention of Jane Austen’s name in print is not in one of her novels (she was credited as “A Lady” in editions published in her lifetime) but in the subscription list of the novel Camilla, or A Picture of Youth (1796) by Frances Burney. It lists those who contributed to the publication costs of the book and contains “Miss J. Austen, Steventon”. Austen paid a guinea (£1 1s or 21s, for those at the back) and it would be the only occasion in her lifetime on which her name appeared in print.

I mentioned after the election of Pope Leo XIV (Robert Cardinal Prevost) this week that he is the first Pope who had been an Augustinian friar. This is true but requires a degree of qualification. Honorius II, Innocent II, Lucius II, Adrian IV and Eugenius IV were all canons regular living under the Rule of St Augustine but not friars: canons regular are a separate category from monks, friars and indeed secular canons. Gregory VIII, whose papacy lasted a shade under two months in 1187, was a Praemonstratensian, a member of the Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré, which was founded in 1120 by St Norbert of Xanten and also follows the Rule of St Augustine.

Leo XIV is, of course, the first American Pope and only the second Pope (after Francis) to come from North or South America. It is worth noting, however, that Francis’s father was born in Italy and his mother was of Italian descent; Leo’s paternal grandparents were from Italy and France, while his maternal grandfather was mixed-race and born on Hispaniola and his maternal grandmother was Black Creole from New Orleans. We are yet to see a Pope from Asia (excepting the Middle East) or Oceania.

By choosing the name Leo (largely, it is believed, in honour of Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903), who opposed Communism, socialism and laissez-faire capitalism and championed social justice and the rights of workers), the new pontiff goes by the joint fourth-most popular papal name (I am discounting antipopes). The others to be used by 10 or more pontiffs are John (I-XXIII), Benedict and Gregory (I-XVI), Clement (I-XIV), Innocent (I-XIII) and Pius (I-XII).

The late Pope Francis did not use a numeral, though presumably he will be numbered retrospectively if and when a future pontiff uses the same name. There are X popes who are the only ones of their name, mostly from the early Church: Peter (of course), Linus, Anacletus, Evaristus, Telesphorus, Hyginus, Anicetus, Soter, Eleutherius, Zephyrinus, Pontian, Anterus, Fabian, Cornelius, Dionysius, Eutychian, Caius, Marcellinus, Eusebius, Miltiades, Marcus, Liberius, Siricius, Zosimus, Hilarius, Simplicius, Symmachus, Hormisdas, Silverius, Vigilius, Sabinian, Severinus, Vitalian, Donus, Agatho, Conon, Sisinnius, Constantine, Zachary, Valentine, Formosus, Romanus and Lando. Since the death of Pope Lando (stop it) in AD 914, no new name was used until the election of John Paul I, and he was succeeded by John Paul II within two months.

Every Pope since 1555 has taken a papal name which is not the name under which he was christened. Marcello Cervini degli Spannocchi was elected to the papacy in April 1555 and styled Marcellus II, but died of a stroke after 22 days in office. His 16th century predecessor Adrian VI (1522-23), baptised Adriaan Floriszoon Boeyens, also used his own name, though the practice of taking a new papal name had started in the 6th century AD and become standard practice by the 10th century.

If popes did keep their own names, the new pontiff would be Pope Robert I, although there was an antipope styled Clement VII (1378-94) whose name was Robert of Geneva; his election by those cardinals in opposition to Urban VI marked the beginning of the Western Schism (1378-1417) which was brought to an end at the Council of Constance (see last week’s round-up). Francis would have been Jorge I, Benedict XVI would have been Joseph I and John Paul II would have been Karol I. Indeed, the only two Popes in the past two centuries to share a baptismal name have been Pius IX (1846-78) and Paul VI (1963-78), who would have been Giovanni XIX and Giovanni XX under that practice. Maybe the Church is on to something, for neatness’ sake.

“Journalism can never be silent: that is its greatest virtue and its greatest fault.” (Henry Grunwald)

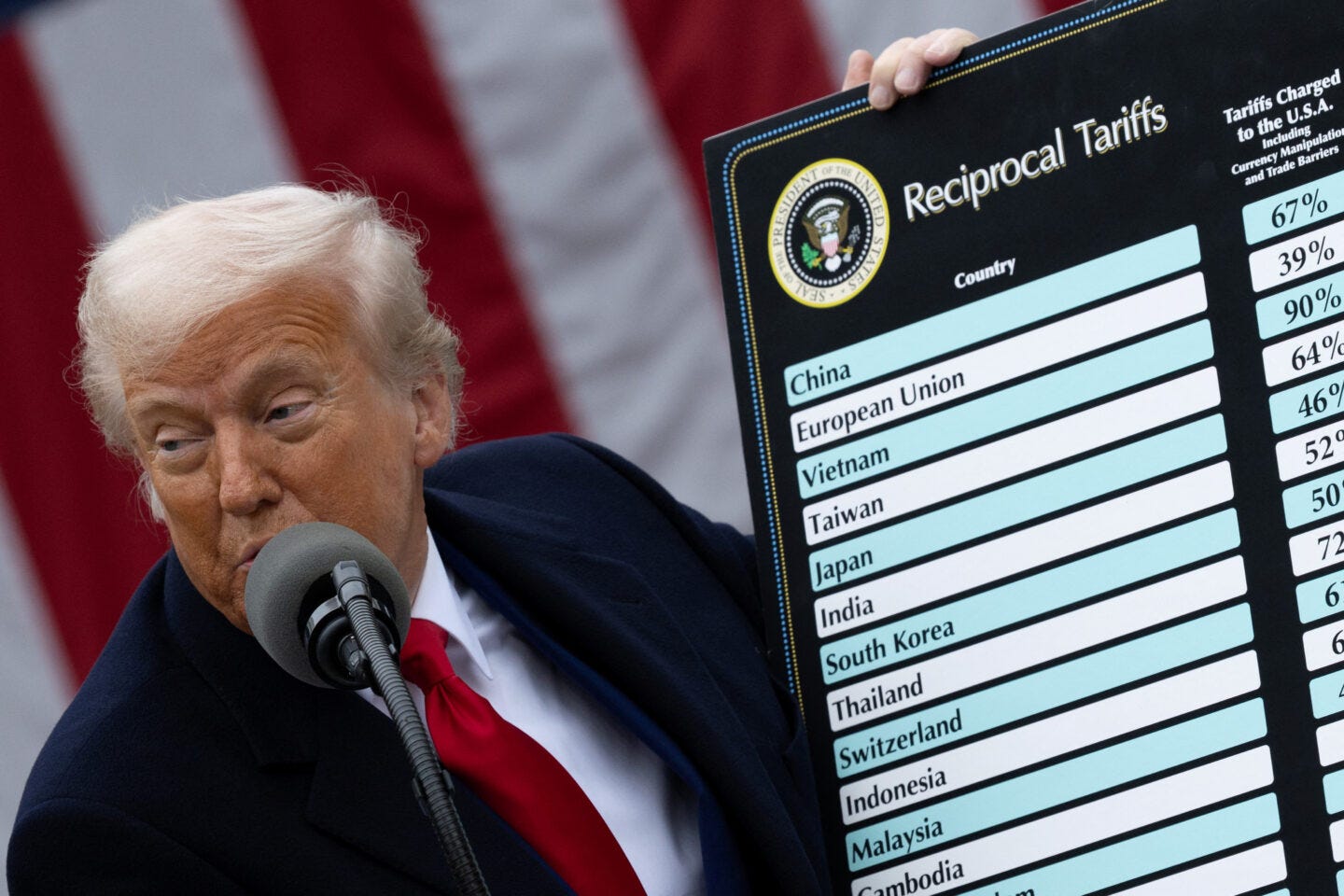

“Trump is all in on a bad economic policy from centuries ago”: making (I believe) her debut in The Washington Post, Kate Andrews, recently appointed US Deputy Editor of The Spectator and (which is of course much greater) a graduate of the University of St Andrews, explains President Trump’s bizarre modern interpretation of mercantilism, “a form of economic nationalism that seeks a big state, trade surpluses and self-reliance”. She argues that the disruption and chaos of the past few weeks should demonstrate “what it took Europe’s leaders centuries to discover: that economic nationalism makes countries poorer”. Trump’s own views on tariffs and protectionism are incoherent, contradictory and propelled by an eerie form of economic mysticism which requires neither evidence nor proof. But Kate quite reasonably points out that it was a repressive expression of mercantilism—the Sugar Act 1764, the Stamp Act 1765, the Townshend Acts, the Tea Act 1773—which spurred Britain’s 13 American colonies into revolt 250 years ago. The lessons are all there, but the President is not much of a reader.

“Why can nobody paint the Royals?”: in The Critic, Alys Denby (who is my excellent editor at City A.M., I should point out) despairs of the portrait of the King and Queen adorning the cover of the latest edition of Tatler. Painted by British-Ghanaian artist Phillip Butah, it is… bad. Really quite bad: flat, lifeless, lacking flair or technical skill and in many respects a poor likeness. But, Alys argues, good modern portraits of royals are thin on the ground, photography finding itself both more expressive and more revealing. In portraiture we seek a kind of intimacy and connection which we will never find but it means that the depictions of royalty say nothing more, while “what’s far more interesting is what their images can reflect back about our own national identity”. Holbein’s Henry VIII, the “Rainbow Portrait” of Elizabeth I, van Dyck’s equestrian Charles I or the monarch as triptych: these are rich in meaning and iconography, with nothing left to chance. We have turned away from something deeply important and expressive.

“Lost Clubs: The Constitutional Club (1883-1979)”: Dr Seth Thévoz knows a lot about London clubs, and I do mean a lot. He has written two books on the subject, Club Government: How the Early Victorian World was Ruled from London Clubs and Behind Closed Doors: The Secret Life of London Private Members’ Clubs. It is therefore no surprise that his Substack deals with clubs, and he has written several fine essays of defunct clubs, of which this is the latest. The Constitutional Club was established in the golden age of London clubs, just before the Representation of the People Act 1884 extended the electoral franchise which applied in towns and cities to the countryside and increased the electorate from 3,040,050 to 5,708,030. It was created with the intention of attracting a much larger membership than the older, more elitist clubs like White’s, Brooks’s and Boodle’s, and “the target audience was made up of new, lower-middle-class provincial voters with a strong party affiliation, who did not already have a London club”. Its inspiration was the Conservative Club in Glasgow and the Marquess of Abergavenny , a reliably grand and wealthy landowner who seems to have been given a marquessate for no particular reason at all, oversaw its establishment, temporarily at 14 Regent Street and then in purpose-built premises on Northumberland Avenue. I will leave the rest of the story to the Substack but it is a fascinating tracing of the evolution of British politics over the course of a century.

“Studying Dickens at university was once considered demeaning. Now it’s too demanding”: a handy two-for-one here, as novelist and critic Philip Hensher (a former clerk in the House of Commons, no less) gives a thunderingly lukewarm appreciation of Stefan Collini’s new Literature and Learning: A History of English Studies in Britain. What Hensher is really doing, however—and he is absolutely right to do so—is acidly cataloguing the surprisingly recent rise of the academic study of English literature and its abject decline in rigour, scope and ambition over the last 30 years or so. It can feel like a lazy lapse into pastiche anti-woke ranting, but it really does seem, from so much I’ve read now, that there are swathes of young people, including those reading for degrees at respected universities, who simply cannot, because they will not, read continuous prose of any substantial length. And no-one insists that they do. Hensher rightly draws attention to “the magnificence and inexhaustible fascination of literature in English”, surely the richest, most varied, flexible and widely undersood language there has ever been. We have access to a treasure trove, and the bar for entry is so low: just pick up a book and start reading.

“Congress shouldn’t be an assisted-living facility”: former Governor of Indiana and President of Purdue University Mitch Daniels uses the announced retirement of Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois to highlight the extent to which the United States Senate has become an aged institution with an average age in the late 60s. Durbin will be 81 later this year, and has been a senator for nearly 30 years, after 14 years in the House of Representatives. In The Washington Post, Daniels argues that in such a small body as the Senate, with only 100 members, the strengths and weaknesses of each individual have a huge impact, and Durbin is one of six aged 80 or over, and one of 35 over 70. There is an uncomfortable truth in what Daniels says: “When even those who are inventing and developing artificial intelligence and genetic engineering do not pretend to fully understand where these breakthroughs are heading, we need political leaders who have grown up with these wonders and find them at least slightly less mysterious.” (I touched on this issue more broadly across American politics in The Hill in February.) Young people do not have all the answers, but they do make a distinct contribution, and Capitol Hill is looking rather grey in recent years.

Great is the art of beginning…

… to quote Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, but greater is the art of ending. Hmmm. We’ll see. TTFN.

"Leo XIV is, of course, the first American Pope and only the second Pope (after Francis) to come from North or South America."

This makes no sense. Surely Francis was the first American Pope and the first South American Pope, and Leo is the second American Pope and first North American Pope?