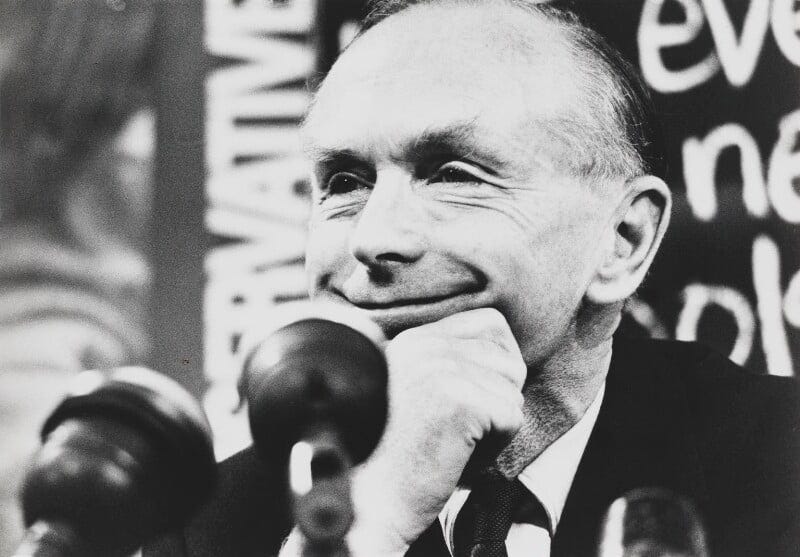

Part 3: Home as prime minister 1963-64

Alec Home is remembered as the inevitable coda of a dying government, but there was nothing inevitable about election defeat in 1964 and it was a close-run thing

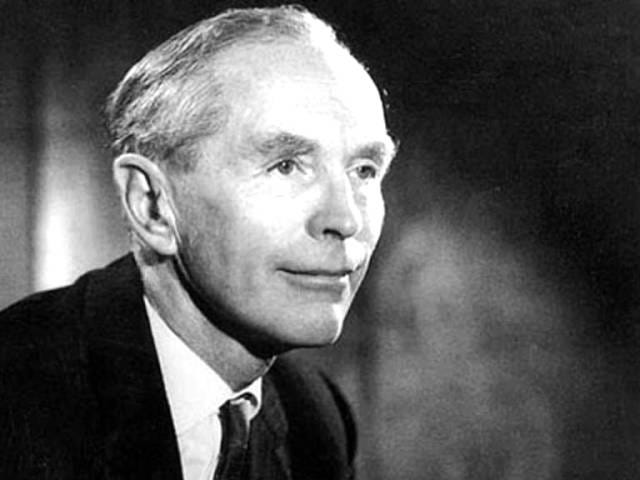

Finally we come to what I really wanted to talk about, which is how Alec Home, an unlikely and slightly reluctant prime minister, performed at the end of a long period of Conservative government. We saw in Part 2 that for a moment it looked as if Alec might not be able to form an administration: there was considerable disquiet in the party at the method of his selection, and a huge amount of power—theoretically—lay in the hands of Harold Macmillan’s nominal deputy, Rab Butler. Nothing in counterfactual history can ever be certain, but it seems highly probable that if Butler had refused to serve under Home, in which refusal he would have been joined by Iain Macleod and Enoch Powell, and possible Reggie Maudling as well, then Alec would have given up and told the Queen he could not form a cabinet. Under those circumstances, it is hard to imagine that the monarch would then have sent for anyone but Butler.

That was not in Rab’s nature. Clever, experienced, politically shrewd and often witty, he was, however, chronically indecisive and prone to hesitate at the last minute. So he agreed to serve in Alec’s government, and was at last given the job he had craved for a quarter of a century, secretary of state for foreign affairs. He was aware of the limitations: the government would have to go to the polls by October 1964, only a year thence, and Butler suspected that Labour would win, so he felt keenly the temporary lease on the Foreign Office. He quickly, and perfectly properly, moved into the foreign secretary’s official London residence, 1 Carlton Gardens, and it was known that his wife, Mollie, was looking forward to the international travel her husband’s role would involve. But he was also aware that the premiership had now probably gone forever (I wrote last year about why foreign secretaries infrequently make the transition to Downing Street).

The rest of Alec’s top team came together relatively easily. Maudling had agreed to remain as chancellor, his political stock still high though a little diminished by his hint of dithering over the leadership; the rather bloodless Henry Brooke, a classmate of Butler’s from Marlborough who had become a favourite target of the new wave of satire, remained at the Home Office; Peter Thorneycroft, who had resigned as chancellor in 1958 and was starting to look less like a bright young thing, continued as minister of defence; and Quintin Hailsham, having promised to disclaim his peerage, honourably did so and soon became MP for St Marylebone, but now looked rather underemployed as lord president of the Council and minister of science. There was a feeling of proper restitution when Selwyn Lloyd, brutally sacked from the Treasury in Macmillan’s infamous ‘Night of the Long Knives’ the previous summer, returned to the cabinet as leader of the House of Commons.

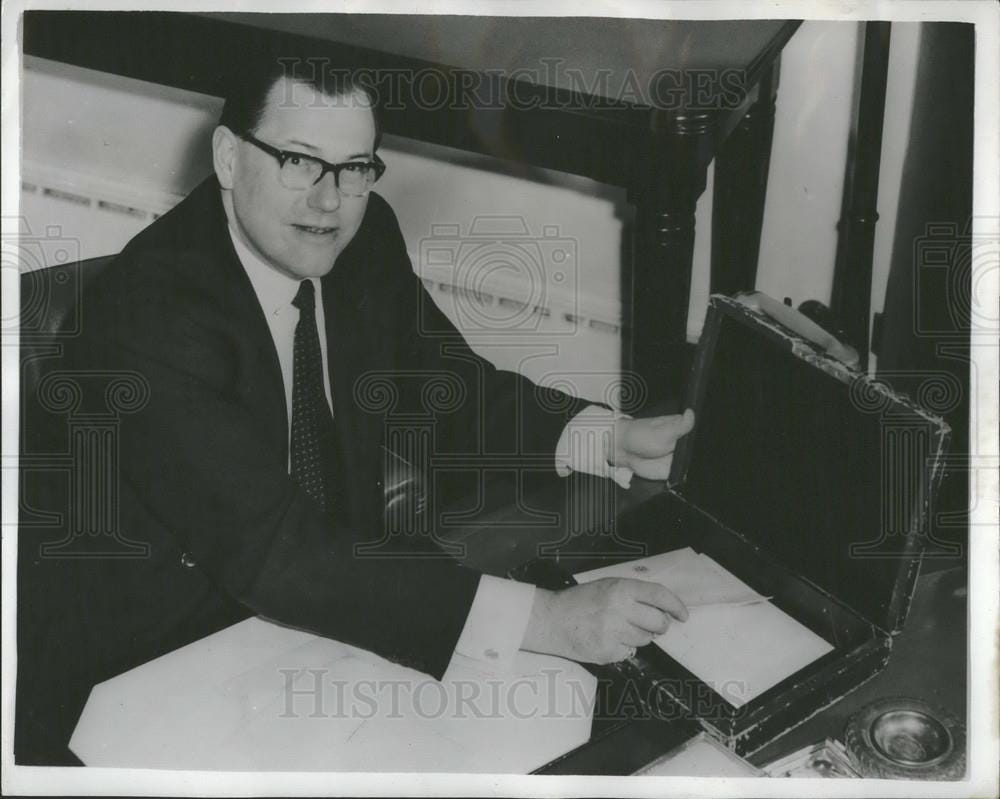

But perhaps the biggest winner was Edward Heath: for three years he had been Lord Privy Seal, Alec’s deputy at the Foreign Office and the minister in charge of the UK’s application to join the European Economic Community, which President de Gaulle had vetoed in January. He was appointed to the mid-ranking position of president of the Board of Trade, responsible for trade policy, industrial development, monopolies, consumer protection and, among other things, the Patent Office. But he was also given the additional, perhaps more modern-sounding position of secretary of state for industry, trade and regional development, which touched on some early-1960s hot-button issues like a government-inspired industrial strategy and interventionist regional economic development.

The traditional, slightly lazy view of Alec Home’s premiership is of a sterile coda, an inevitably winding down of the Conservative government towards defeat at the general election of October 1964 and the inauguration of the 1960s ‘proper’ with Harold Wilson’s Labour administration. Douglas Hurd, private secretary to Sir Harold Caccia, head of the Diplomatic Service, described the government as “becalmed in a sea of satire and scandal”. One is almost invited to imagine ministers, MPs and civil servants pacing impatiently, counting off the weeks and days until the great change can be effected.

It is a frequent hazard of historiography to see events as preordained, of seeing patterns which lead to conclusions which could not have transpired any other way. Of course the Tories would not win a fourth general election, the received wisdom holds; of course they would not overcome the Vassall and Profumo scandals; of course the tweedy, aristocratic Alec Home would not be able to embody a modernising Britain and defeat the limelight-loving but deliberately ordinary Harold Wilson. Indeed, reminiscent of the Conservative Party’s choice of Iain Duncan Smith to face Tony Blair in his pomp in 2001, Alec Home could hardly have been, prima facie, a less suitable leader and public face. Defeat was written.

The situation which Alec Home faced as prime minister was far from dismal. The economy was vibrant and growing at four per cent per year and exports were healthy. Inflation was a manageable two per cent, and unemployment had averaged around two per cent for more than a decade, with full employment still a key economic objective of successive governments. Sterling was pegged at $2.80 and Maudling “reject[ed] the proposition that a vigorous economy and a strong position for sterling are incompatible”. The chancellor’s 1963 budget, delivered in April, was billed as delivering “expansion without inflation” and had included modest tax cuts, such as the abolition of income tax on residential premises and of the duty on home-brewed beer. In the dirigiste world of an incomes policy, wage increases of between three and three-and-a-half per cent weer judged sustainable and widely acceptable.

In foreign affairs, EEC membership was clearly a dead letter for the time being, after President de Gaulle’s decisive “non”. The process of gradual withdrawal from Empire and the independence of former colonies was continuing apace. Since the Conservatives had come to power in 1951, 13 territories had become independent: Libya, Sudan, Ghana, the Federation of Malaya, Somaliland, Cyprus, Nigeria, Sierre Leone, Kuwait, Tanganyika, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uganda. The majority had become members of the Commonwealth. Many other colonies were preparing to declare their independence, and the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, created in 1953, was fast approaching the point at which it would dissolve and its member states go their own way (though it was not at that point foreseen how protracted and painful a journey Southern Rhodesia would undergo before finally achieving majority rule in 1980).

In broader terms, just coming into effect as Alec Home became prime minister was the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, more snappily known as the Partial Test Ban Treaty. This had been agreed in Moscow in July, spurred on in part by anxiety following the Cuban Missile Crisis, and forbade signatories from conducting nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, outer space or underwater, leaving only underground explosions for the future development of nuclear weapons. Initially signed by the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, and by the time it came into force on 10 October, another 90 states had signed it. Although it fell short of a full test ban, it was regarded as a significant step towards de-escalation of the nuclear arms race: broadcasting to the nation, President John F. Kennedy emphasised the stakes by reminding his audience that a full-scale nuclear war between East and West was likely to last less than an hour, and would kill 300 million people.

In terms of pure politics, while Conservative faces were long, the situation for the government was not what we would think of today as desperate. The first polls taken after Alec’s succession put the Conservatives on 41 per cent, and Wilson’s Labour opposition on 48.5 per cent. The Liberals, their “revival” after the 1962 Orpington by-election already waning, were at around 10 per cent and found it difficult to make much headway. The gap had been considerably worse: in the summer, Labour had been up to 20 points ahead. Nevertheless, a deficit of 7.5 per cent was no road to victory for the government, and the received wisdom was that Alec Home was not the man to pull it back.

Presentation was acknowledged as a serious problem. Television ownership had doubled in six years, and quadrupled in nine, while cinema attendance, where newsreels were shown, had plotted almost exactly the reverse trend, making the small screen a vital political battleground. For reasons which were not entirely easy to identified, Wilson shone on television. It didn’t obviously make sense: a childhood episode of typhoid fever had left him stooped, his looks were undistinguished and his West Yorkshire accent—hardly broad but noticeable for a leading politician of the time—could sound nasal. But television made him sparkle, favoured his agile mind and emphasised his relative ordinariness, his spirit of everyman in a country supposedly weary of class distinctions.

Alec was quite the opposite. His appearance did not work well on camera, and his resemblance to a caricatured skull, the sort of thing usually seen on a Jolly Roger, was a running joke. An exchange with a make-up girl before a television appearance during the 1964 election summed up the problem.

“Can you not make me look better than I do on television? I look rather scraggy, like a ghost.”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because you have a head like a skull.”

“Doesn’t everyone have a head like a skull?”

“No.”

Lady Douglas-Home felt that Alec’s half-moon reading glasses compounded his old-fashioned appearance. More of an obstacle, however, was his intonation. While neither Macmillan nor Eden had been cursed with a vulgar tongue, and Macmillan’s studied Edwardian image included a drawl which could make syllables last forever, Alec had what could have been a parody of an aristocratic accent, speaking without apparently moving his jaws; he also bore more than a passing resemblance to the puppet Lord Charles, then appearing on television with the young ventriloquist Ray Alan.

Undoubtedly the great satire boom of the 1960s was another factor. The now-legendary Beyond the Fringe, a revue show by Oxbridge stars Alan Bennett, Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore, had first been performed at the Edinburgh Fringe in August 1960 before transferring to London’s West End then Broadway. It was an astonishing success, revolutionary in mocking without apology figures like Churchill and Macmillan, Peter Cook’s savage impersonation of the latter hitting particularly hard; the prime minister hated the caricature of a doddery, forgetful old man, though it was only by a matter of degrees different from the impersonation Macmillan performed of himself. Kenneth Tynan, the Angry Young Man of theatre criticism, described the revue as “the moment when English comedy took its first decisive step into the second half of the twentieth century”.

The satirists themselves, from Beyond the Fringe to That Was The Week That Was, shone brightly but some were aware of their own limited impact. When Peter Cook founded the Establishment Club, a music and comedy club on Greek Street in Soho, he remarked that it was inspired by “those wonderful Berlin cabarets which did so much to stop the rise of Hitler and prevent the outbreak of the Second World War”. Michael Cockerell, in his history of prime ministerial television appearances, says of Alec there was “no modern politician seemed less well-equipped to deal with television”; watching some of Quintin Hailsham’s outbursts on camera during the summer of 1963, like his bad-tempered assault on Canadian broadcaster Robert McKenzie, one might perhaps disagree. And it is easy to think that satire changed the landscape of politics, when in fact much of it was playing to the choir, delighting and reinforcing the beliefs of those who already thought (and voted) in particular ways. But it could articulate an inchoate feeling already brewing among the voters, and That Was The Week That Was may well have done so when, towards the end of 1963, David Frost performed a Christopher Booker-penned soliloquy which characterised the following year’s general election as a case of “Dull Alec versus Smart Alec”.

So was it a lost cause? Was Alec fated to draw a line under a long period of Conservative rule and leave the furniture tidy for an incoming Harold Wilson? Or were there plausible events which could have gone differently and given the government the chance of staying in power? John Major would show in 1992 that four election victories on the bounce were not impossible (so too, under more complicated circumstances, would Boris Johnson in 2019), and in truth the Labour Party, despite 13 years in opposition, where soul-searching is traditionally done, still had many internal questions unanswered.

The Attlee government which triumphed over Churchill in 1945 is—with good reason—remembered as transformational, a genuine watershed in British politics. What is less easily recalled is how quickly it ran out of steam: by 1948, at the latest, it was beginning to struggle, partly due to world events and partly due to a simple lack of momentum. The general election of February 1950 saw the government’s majority reduced to only four, and another election was called only 18 months later, which the Conservatives won. The Labour Party was visibly exhausted—some ministers had, after all, been in office almost continually since 1940—with Attlee, nearing 70, determined to retain the leadership at least long enough to scotch the chances of Herbert Morrison, who had been his de facto deputy from 1945 to 1951 but whom he neither liked nor trusted. And it went into opposition with a dilemma.

Effectively, as so often, two wings of the Labour Party had drawn different lessons from their period in government. One side, led by the outgoing chancellor, Hugh Gaitskell, believed that the party had to shift towards a moderate, European-style social democratic platform if it was to remain competitive in the marketplace of ideas. This position would be distilled in Anthony Crosland’s 1956 text The Future of Socialism. The other perspective was that the party had lost its ideological way amid the strains and stresses of governance, and needed to embrace more radical socialism. Leading this charge was the powerful Welsh orator Aneurin Bevan, father of the National Health Service, around whom left-wing Labour MPs had started to coalesce after he resigned from the cabinet in 1951 in protest at the imposition of charges for spectacles and other items previously provided by the NHS; Harold Wilson, then the young president of the Board of Trade, had resigned with him, and became known as “Nye’s Little Dog”.

When Attlee finally retired as leader in 1955, Gaitskell comfortably beat Bevan 157 to 70 in the ballot of Labour MPs to succeed him, Morrison, by then in his late sixties, limping in a distant third, with 40 supporters. Bevan was widely felt to have been disloyal and factional in the years since 1951; Richard Crossman, the future minister and diarist, observed that he “wasn’t cut out to be a leader, he was cut out to be a prophet”. When Bevan remarked “I know the right kind of political leader for the Labour Party is a kind of desiccated calculating machine”, it was taken as a barb aimed at Gaitskell, who had read PPE at Oxford, worked in the civil service during the war and then served as chancellor of the Exchequer. Nevertheless, Gaitskell held out an olive branch to him, appointing Bevan first shadow colonial secretary then, after a few months, shadow foreign secretary. There seemed to be a slight upswing in Bevan’s position: when the election for a new deputy leader was held in February 1956, he was beaten by Llanelli MP Jim Griffiths, but only by 141 to 111, a much narrower margin than had been expected.

Gaitskell’s election as leader, and the triumph of his ally Griffiths as deputy leader, did not, however, resolve the underlying tension in the Labour Party as it might have been expected to. Divisions between Gaitskellites and Bevanites rumbled on over nuclear disarmament (which Gaitskell opposed) and the UK’s pro-American, anti-Soviet foreign policy (which Gaitskell supported), and when the Conservatives won again in 1959, the Labour leader blamed Bevanite agitation over economic policy. He also maintained a position of scepticism over EEC membership. The schism rumbled on, but as the 1960s began it was unexpectedly robbed of its champions: Bevan died of stomach cancer in July 1960, and Gaitskell was killed by a flare-up of lupus in January 1963. Harold Wilson, shadow foreign secretary and chairman of the Public Accounts Committee, beat George Brown and James Callaghan to become the new leader and a fragile unity, given focus by the impending general election, began to emerge, but it was hard to say that the fundamental philosophical differences had been settled.

If this was the opposition, the supposed government-in-waiting, how did the real administration fare under Alec Home? The first major event, just five weeks after Alec became prime minister, was the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on 22 November. Alec had known and liked Kennedy from his time as foreign secretary (1960-63), and, although he lacked Macmillan’s tortuous familial connection (Lady Dorothy Macmillan’s nephew had been married to Kennedy’s sister), he gave a sober but honest and moving tribute to the president on television only hours after his death was announced. It was Alec at his best, unfussy, straightforward and decent: whatever other qualities he had or did not have, he always looked the part.

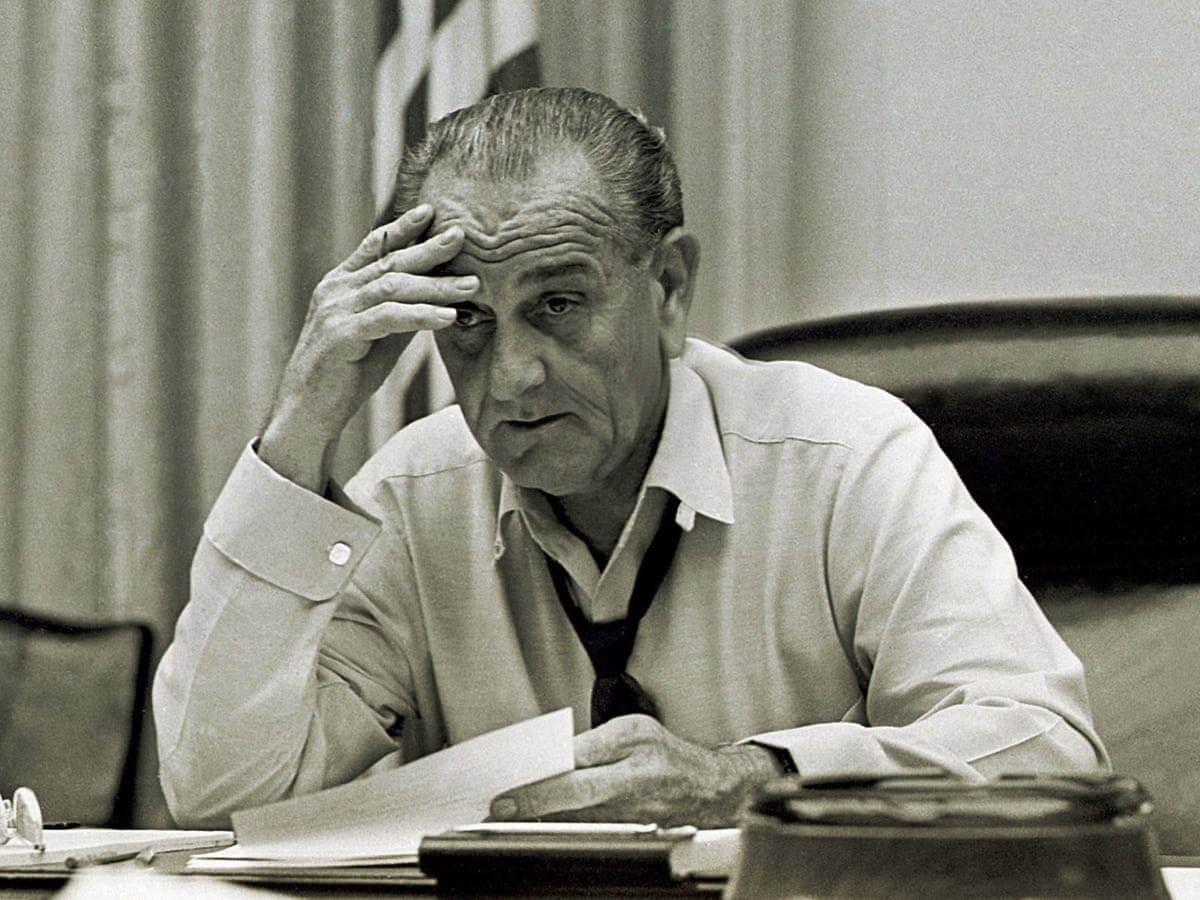

Alec’s relationship with Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, was never especially warm. They were very different people, the courteous, self-deprecating Scottish aristocrat and the expansive, overbearing, crude wheeler-dealer from the central Texas hill country. Johnson was blazingly ambitious, while Alec would have been quite happy fishing in the Tweed rather than occupying Downing Street. Equally, the British ambassador in Washington, David Ormsby-Gore, was a former Foreign Office minister, heir to Lord Harlech, who had known Jack Kennedy in London in the late 1930s and was good friends with his widow Jacqueline (indeed, Ormsby-Gore would propose to Mrs Kennedy in 1968, but was affectionately refused). Although he had good relations with President Johnson, they were correct rather than warm. His counterpart in London, David Bruce, had run the European operations of the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor of the CIA) during the Second World War before serving as US ambassador to France (1949-52) and West Germany (1957-59); appointed to the London embassy by Kennedy in 1961, he was confirmed by Johnson but ceased to have any real influence in the White House.

A difference of policy emerged between the US and the UK on relations with Cuba. After the failed CIA-backed invasion at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961, American policy became focused on trying to destabilise and undermine Fidel Castro’s Communist régime. The Foreign Assistance Act passed by Congress in September 1961 prohibited aid to Cuba and gave the president the power to impose trade restrictions on the island, which were increased over the next months until by September 1962 there was a more-or-less total trade embargo. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy then imposed travel restrictions, and in the summer of 1963, the Cuban Assets Control Regulations completed the sanctions.

Other western nations were not so cautious, however. The UK continued to trade with Cuba, and in January 1964, the Leyland Motor Corporation announced that it had sold 400 Olympic buses to Cuba in a deal worth £4 million, building on a commercial relationship which dated back to 1949, and which promised further acquisition in the future. Alec and Lady Douglas-Home visited the White House in February 1964, and the issue of the Leyland deal dominated the summit. George W. Ball, Under-Secretary of State and number two at the State Department, wrote to Johnson before the summit, reminding the president “The recent sale of buses has had and will have grave consequences for our denial program by undercutting our efforts with other countries.”.

Johnson was obsessed and angry, feeling that the UK was not showing solidarity with its supposedly closest ally, and the head of chancery in the British Embassy, John Killick, warned in advance that any glib or excessively upbeat remarks on the deal would not go down well. Alas his advice went unheeded. As Alec left a meeting with Johnson, he was drawn into conversation with members of the press on the White House steps, and referred to the sale of buses. Dean Rusk, Johnson’s secretary of state, recalled afterwards that this had been deeply awkward.

That caused President Johnson some resentment because he felt that if Sir Alec wanted to talk about trade with Cuba, he ought to talk about it in the House of Commons back home and not talk about it on the front steps of the White House.

It would, for all that it seemed a minor matter, colour Anglo-American relations for the rest of Alec’s premiership. The joint communiqué issued after the summit was blandly collegiate on trade with the Castro régime.

The President stressed his concern at the present situation in the Caribbean area and the subversive and disruptive influence of the present Cuba[...] regime. The Prime Minister fully recognised the importance of the development of Latin America in conditions of freedom and political and economic stability.

(There was one amusing side-note to the summit, contained in the US record of the meetings. Discussing the situation in Cyprus, where a United Nations peacekeeping force had been inserted to try to prevent inter-communal violence between the Greek and Turkish populations, the hosts looked to Alec and the rest of the UK delegation for expert insights, as Britain had controlled the island between 1914 and 1960. Johnson “asked Sir Alec what motivates Makarios”. Alec, inimitably and perfectly illustrating the unbridgeable gulf between himself and the president, responded, according to the note-taker, Gordon Knox of the State Department: “Sir Alec called Makarios a stinker of the first water”.)

In the House of Commons, Alec was smooth and emollient. Asked about the implications of the Leyland deal by John Mendelson, Labour MP for Penistone where some jobs would be supported, he played down the suggestion that the US might impose a boycott on British goods as a punishment.

I do not think that the hon. Member should anticipate all these troubles. I have no reason to believe that the United States Government would in any way support a boycott of British goods.

Pressed by Wilson about the possibility of British ships which had transported goods to Cuba, he again denied that this was a likely prospect.

We have constantly told the American Government that freedom for shipping is of cardinal importance to the United Kingdom. The measure which the United States has adopted is to prohibit the carriage of United States Government cargoes in ships of any nationality which have called at Cuban ports since 1st January, 1963. This decision was taken before the question of buses raised by the hon. Member arose. It is true that some British ships have had difficulty in United States ports, but I am bound to add that the difficulty that British ships have suffered up to now has been because of the opposition of the United States trade union and not of the United States Government.

However reassuring the prime minister might try to be, however, the “special relationship” had been damaged. Johnson operated very much on instinct and personal warmth or antipathy; after February 1964, he regarded Alec as an inconvenience, but one which, he judged, was likely to leave the scene at the forthcoming general election, hopefully to be replaced by a more tractable figure.

Elsewhere in international affairs, the decolonisation process was continuing, though much of it had been set in motion before Macmillan had stepped down. The biggest issue on this front was the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, which was made up of the three territories Cecil Rhodes had carved out. Created in August 1953, it was an awkward beast in administrative terms, as Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were protectorates while Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing colony. As a result, the first two territories were overseen by the Colonial Office in London, while Southern Rhodesia came under the supervision of the Commonwealth Relations Office (which Alec had run from 1955 to 1960). In 1962, Macmillan, always on the look-out for ways to keep Rab Butler occupied, created the Central Africa Office to look after the federation, with Rab, as First Secretary of State, as the responsible minister.

Alec scrapped the Central Africa Office when he moved Butler to the FO. In any event, since July 1962, the Colonial and Commonwealth Relations Offices had shared a secretary of state, Duncan Sandys, and Alec was on record as supporting the merger of the CO and the CRO. It had been agreed at a summit at Victoria Falls in summer 1963 that any of the three components of the federation could secede, and Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia both seemed inclined to do so. At the stroke of midnight at the end of 1963, the federation was dissolved; in July 1964, Nyasaland became independent as the Republic of Malawi, though its first constitution made it a one-party state; weeks after the general election in 1964, Northern Rhodesia became independent as the Republic of Zambia; while Southern Rhodesia returned to its status as a colony and renamed itself simply Rhodesia but was slipping towards terminal disagreement with the government in London, and unilaterally declared independence in November 1965.

On the home front, the only significant piece of legislation was the abolition of resale price maintenance (RPM), an agreement between manufacturers and distributors to keep prices above a certain level and avoid undue competition. The Monopolies and Mergers Commission had recommended the end of RPM, and had informed the Restrictive Trade Practices Act 1956, which required restrictive trading to be recorded on a public register unless granted an exemption by the secretary of state. But this was an unsatisfactory halfway house and operated an excessively complex system of exemptions. Moreover these exemptions still applied to around a third of goods, and were clearly to the disadvantage of the consumer. The most powerful sector supporting RPM was that made up of pharmacies which claimed that their survival as small businesses relied on the ability to guarantee a certain level of income.

RPM was clearly not in the interests of consumers, and its proposed abolition drew warm words from the Parliamentary Secretary for Pensions and National Insurance, Margaret Thatcher, talking to her local chamber of commerce, as well as attracting the support of Ralph Harris’s Institute of Economic Affairs. The IEA had been since its foundation in 1955 the brains trust for monetarist economic thought which was gradually being espoused by radical-minded Conservatives like Enoch Powell, and had published a pamphlet by the South African economist Basil Yamey recommending the abolition of RPM in 1960. However, the Conservative Party was not wholehearted in its support for the move.

The situation, in brief, was that RPM, while disadvantageous to consumers, was felt to be vital to small retailers who were believed to be a core constituency for the Conservatives. Alec was not keen on the idea, and recorded that it would be “very difficult”. But it was Heath, with his new economic portfolio, who was keen to seem modernising, radical and bold, showing his abilities in a major cabinet position after a dozen years in the Whips’ Office and as a Foreign Office negotiator, less nine months as minister of labour in 1959-60. Alec came to view the situation in very binary terms: either he must, reluctantly, back the president of the Board of Trade, or he would be forced to move Heath to another post. The latter option seemed excessively drastic and perhaps made Alec reflect on how much he really cared. So he allowed Heath to go ahead.

The Resale Prices Bill was not a major piece of legislation. In fact, it was a particular kind of proposed law, a consolidation bill, which is usually fast-tracked through both Houses because it does not introduce major new policy but instead brings together existing statutes into a simplified, unified act. (There is a Joint Committee on Consolidation, &c., Bills to scrutinise these instruments, of which I was the House of Commons clerk from 2009 to 2010: during my tenure it never met, and indeed the chairman, Viscount Colville of Culross, was dead.) The Resale Prices Act 1964 was, nevertheless, regarded as a significant change of direction for the government, turning away from the traditional shopkeepers of which England was famously a nation and showing a flash of the kind of deregulatory zeal which would flourish in the Conservative Party after 1975. In fact, greater opposition to the legislation came from manufacturers than small retailers.

Much criticism has been levelled at the Resale Prices Act on the grounds of its medium- to long-term operation and how it worked in connection with the system of recommended retail prices (RRP), set by manufacturers, which came to replace it. This seems at least slightly unfair: the Resale Prices Act did not even come fully into effect until April 1965, more than six months into the Labour government, and it hardly seems reasonable to hold Alec’s administration of 1963-64 responsible for the economic conditions which would obtain over the turbulent years of Wilson’s premiership.

One overlooked factor about the abolition of RPM was that it was a policy backed by the Co-operative Party, which since 1927 had been allied to the Labour Party and which ran candidates on a joint ticket. Although it had a separate organisation and legal identity, chaired at this point by Lord Peddie, it was in effect a fraktion within Labour. Sixteen Labour/Co-operative MPs had been returned in 1959, and one of them, John Stonehouse, the Member for Wednesbury, introduced a private Members’ bill in December 1963 proposing the abolition of RPM. When he moved the Second Reading of the Abolition of Resale Price Maintenance Bill in January 1964, he set out a list of countries which had already scrapped RPM, before giving a concise argument in favour of the measure.

Why should resale price maintenance be abolished? Because it encourages barnacles to grow on the economic ship. We want to clean those barnacles off so that we can have a smooth running economic system. There are, I think, four main arguments against RPM. First, it imposes a rigid price system; secondly, it encourages inefficiency in retailing; thirdly, it is injurious to the customers; fourthly, it also encourages inefficiency in manufacturing.

It is interesting to see the common ground here between the Co-operative Party and the new economic radicals of the Tory right. Some of the disputes were over interpretation of words: Leslie Hale, a former Liberal who was by then Labour MP for Oldham West, criticised the Conservatives because they “have talked about being the apostles of private enterprise, yet they have shoved the smaller people into the hands of the great wholesalers and the great combines”, clearly identifying small businesses as a “truer” kind of private enterprise. And that perspective was the one many traditional Tories cleaved to, while others interpreted private enterprise more widely; the focus for them was the consumer, and if greater prosperity for larger retailers like supermarkets ultimate brought prices down and drove efficiency up, well, then that benefited everyone.

Stonehouse’s bill came to nothing. David Price, the junior Board of Trade minister, criticised not only the structure and provisions of the bill but its whole thrust, while Douglas Jay, the Labour spokesman, twitted the minister for the fact that the government had yet to bring forth its own bill. Stonehouse’s bill was denied a Second Reading, leaving him to achieve later fame as a rising ministerial star, agent for Czechoslovakian intelligence and famous fugitive from justice. His Labour Party allies paid little attention. The party described the abolition of RPM as “tinkering” and had far bigger economic fish to fry, with plans for much more comprehensive central planning and government direction of the country’s means of production.

The effect of the dispute over RPM within the Conservative Party has been exaggerated. It was undoubtedly a controversial measure which exposed a perennial division between the exponents of a free market and the defenders of vested, small-business interests, but the theological arguments were muted in a party which had, for some time, been notably unideological. In fact, as Anthony Howard noted in The New Statesman, the issue was a personal one.

Ted Heath’s name had become a highly incendiary one with a good many of his cabinet colleagues… it has very little to do with RPM and a good deal to do with the flawless gymnastic exercise he performed last summer in leaping from bandwaggon to bandwaggon and finally landing on the right one at exactly at the right time.

In the end, after the controversy in Parliament in May and June 1964 died down, it is hard to see that the abolition of RPM had any significant effect on the result of the general election. Labour’s lack of interest meant that it did not feature in partisan clashes, and if it damaged the Conservative cause with some people for whom the prosperity of small retailers was an overwhelming consideration, it was more or less neutralised by those who welcomed it as a pro-enterprise measure and saw it as part of a wider sense that, even after 13 years in office, the Tories could still muster a spirit of modernisation and take on outdated practices which were holding Britain back.

As the inevitable election approached in 1964, it was clear that, whatever criticisms were directed at Alec personally, the Conservatives had narrowed the gap in the opinion polls dramatically. Labour had led by 10 points when he had taken over in Downing Street, but by mid-August 1964, the Conservatives went ahead by one per cent, and did so again at the beginning of September. The deficit to Labour was now around five points at worst, and throughout the month before Parliament was dissolved, the parties were effectively neck-and-neck. This was an extraordinary achievement. Remember that the government had been written off as a condemned man in 1962-63, and episodes like the Profumo affairs and the resignation of Macmillan, with the controversy over his successor which followed, had been seen as nails in its coffin. That seemed a reasonable expectation: 13 years in government was a long time, with three election wins at each of which its majority had increased, and the spirit of change was in the air. Yet with weeks to go, the evidence said that the election could go either way.

One reason seems to have been Alec’s decision to focus on a few simple issues, one of which was the maintenance of the UK’s independent nuclear deterrent. In April 1963, the UK and the US had agreed a deal which would supply Polaris, the new submarine-launched ballistic missile system, to be carried by five submarines. Reporting on the Polaris Sales Agreement to the House of Commons, Alec emphasised that the deal “impose[s] no restrictions whatever, military or political, about the use of the Polaris missiles” by the UK: this was, in his description, a wholly independent weapons system.

Making the deterrent a key election issue was good politics: the Conservative Party was united behind acquiring and operating Polaris, especially after the cancellation in 1960 of the land-based, British-built Blue Streak missile, while the Labour Party had a strong body of opinion which favoured unilateral disarmament or reliance on the American “nuclear umbrella” rather than an independent UK deterrent. Wilson dismissed Polaris as the “Tory Nuclear Pretence”, but it was an uncomfortably divisive subject for him: the 1960 party conference had passed a resolution in favour of unilateral disarmament, despite a mesmerising performance by Gaitskell, to a noisy hall, in which he promised to “fight, fight and fight again to save the party we love”. The Parliamentary Labour Party had nonetheless voted in favour of the 1961 Defence Estimates, the five MPs who voted against having the whips removed, which displayed the gap between parliamentarians and conference delegates.

It was true that Alec had some tricky moments during the election campaign, experiences which the slicker Wilson might well have shrugged off or even turned to his advantage. A week before polling day, appearing at the Rag Market in Birmingham, he was received with a wall of noise from a crowd of 7,000, some opponents chanting “Tories out!” and “We want Wilson!”, other supporters shouting back to drown them out. Alec spoke on undaunted, remarking at one point that if the audience couldn’t hear what he was saying then they could always read about it in the next day’s newspapers, and Geoffrey Lloyd, chairing the meeting, praised the prime minister’s courage in facing so many detractors. But the event was televised and the nation saw a leader barracked into inaudibility. The co-chairman of the party, Lord Blakenham, said later it was the moment at which he began to feel any prospect of victory slide away.

At another meeting, speaking in favour of Christopher Soames at Bedford (with whom he intended to replace Butler as foreign secretary in the event of an election victory), Alec was heckled by a man who offered him a box of matchsticks, a satirical reference to his admission that he used matches to illustrate economic problems to himself. Dealing with hecklers in a large noisy crowd was not the best setting for Alec’s dry, self-deprecating humour, and it reinforced the view of a man battling against the odds.

And yet… and yet, despite all the disadvantages of a scandal-riven party, and out-of-touch image, a controversial succession, refusals to serve by senior ministers, and a supposedly uncharismatic leader facing a master of presentational arts, Alec very nearly pulled it off. A narrowing gap in the opinion polls towards polling day on 15 October translated into a result much closer than many had expected. By midday on Friday, the day after polling, it was still not clear who had won; during the night, the prime minister’s principal private secretary, Keith Mitchell, had drafted a memorandum entitled Top Secret and Personal. Deadlock. The Queen’s Government must be carried on, in which he rehearsed the possible courses of action if the election did not produce a clear winner.

The eventual result was that Labour, hardly improving on its share of the vote in 1959, won 317 seats, a gain of 59. The Conservatives lost votes on a six per cent swing, but still accumulated 304 seats. With the Liberals taking only nine, the new government had the slender majority of four, clearly not sustainable over the five-year maximum of a parliament. It would have taken only a few thousand votes here and there for the Conservatives to have remained in office, albeit their majority much reduced on Macmillan’s plurality of 1959.

Two events occurred shortly afterwards which, some believed, might have swung the balance if they had come earlier, and both were in Alec’s comfort zone of foreign affairs. On 14 October, the very day before the UK went to the polls, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union both agreed to accept Nikita Khruschev’s “resignation” as first secretary of the party and chairman of the Council of Ministers, on the grounds of age (he was 70) and illness: in fact it was a coup to remove him, albeit a bloodless one, and Khruschev decided not to fight back. Ruefully he remarked to a colleague:

Could anyone have dreamed of telling Stalin that he didn't suit us anymore and suggesting he retire? Not even a wet spot would have remained where we had been standing.

The news of this coup in the Kremlin only reached London on the evening of polling day, too late for that night’s newspapers, so it was barely a factor in the election. Might it have made a difference a few days earlier? Might the potential for instability at the heart of the great Cold War adversary have caused voters to choose the safety of Alec’s experienced and firm anti-Soviet hand over Wilson’s inexperience? Some informed observers certainly thought so. The British ambassador in Washington, David Ormsby-Gore, wrote to Alec in commiseration: “Almost anything could have tipped the balance. Khrushchev’s removal from office twelve hours earlier…” And Wilson himself, although he could afford to be generous, conceded that:

It was an open question whether, if the news from Moscow had come an hour or two before the polls closed, there would have been an electoral rush to play safe and to vote the existing Government back into power.

The same thought process applied to China’s detonation of its first atomic bomb on 16 October, the day after polling. Project 596 was a uranium-235 implosion fission device tested at the Lop Nur salt lake in Xinjiang, where the test site, built with Soviet assistance, had been active for exactly five years. It yielded “only” 22 kilotons, comparable to the bomb which had devastated Nagasaki in 1945, at a time when the Soviets had generated 50 megatons from their aerial Tsar Bomba device, but it made China the fifth nuclear power and Asia’s first. The prospect of a Chinese nuclear capability had already, years earlier, made President Kennedy contemplate military action, so there was no doubt that this was a significant shift in the balance of geopolitical power. Again, had this happened a week earlier, might the voters have chosen differently on polling day? Again, Ormsby-Gore and Wilson both thought it possible.

This, really, is the point I wanted to make. There was nothing inevitable about the defeat of the Conservative Party at the general election of October 1964. Alec Home proved a capable premier and nowhere near as poor a campaigner as folk memory recalls him; he had some significant strengths; and he overcome huge challenges to hold Harold Wilson and the Labour Party to a very narrow win. At some point I will look at how this ‘other’ 1964 might have turned out: Alec intended to make Christopher Soames foreign secretary and ask Enoch Powell to reform the Whitehall machine, among other initiatives; and I will also examine what effect defeat might have have on the Labour Party (Quintin Hailsham thought it would have been existential, with social democrats combining with Liberals to form a new centre party while the socialist wing of the Labour Party drifted off to the left). But mainly I wanted to correct, even if just a little bit, the rather dismal view that posterity tends to have of Alec Home. Certainly he was the greatest gentleman to hold the office of prime minister in the 20th century, but he was by no means a poor leader either, and perhaps deserved greater recognition that that afforded by the woman on the train to Berwick.