Our political parties shape our identity and their names matter

The United Kingdom has long-established, durable parties which mould us but do not stay relevant by accident; we will need to talk to each other about how they work

In the United Kingdom, although we think about the two processes in very different ways, our major political parties are undergoing major internal and ideological change, change which both stems from and influences how they conceive of themselves. It’s more marked, and maybe deeper-seated, in the Conservative Party: after nearly 14 years in government, under five prime ministers, having experienced some of the most foundational challenges to our political system in the Brexit referendum and the Covid-19 pandemic, the party has lost a coherent narrative, and now contains a number of distinct urges and potential directions.

You will find MPs who want to pursue radical libertarianism, free market economics and a bonfire of controls; others whose overriding concern is border security, and, beyond that, community cohesion and the possibility that multiculturalism might have been a failure. Some are fundamentally statist when it comes to economics, focusing on the preservation of domestic industry, financial support for key sectors and major public investment in infrastructure and services; there is also a faction which promotes family, faith and social conservatism. These debates have not nearly been resolved; indeed, Conservatives have barely been able to frame them coherently.

The Labour Party is undergoing something of the same experience, though it had come further and is being led from the front, as Sir Keir Starmer seeks to reinvent Labour’s policy platform after the Corbyn experiment. It is not without controversy, and social media still bubbles with vitriol for Starmer from some elements on the far Left. It is a regular conceit, as it was for Tony Blair before him, that Starmer is literally indistinguishable from a Conservative, which is plainly absurd, but the fact that Starmer is leading to what looks like an emphatic election victory dampens some of the criticism and allows him to care much less. But anyone who reads Labour’s “five bold missions” will have waded through a lot of verbiage and warm but empty reassurance: you would need to be a true loyalist to find a sharp, coherent and clearly defined intellectual framework in Starmer’s policy offering.

There is a lot to be said about policy, and about the sorts of platforms being assembled and offered to the electorate now. I will come back to this a lot over the course of this year, I’m sure, both here and in the media. I have my own views, as frequently flyers will know. But in this essay I want to look at party identity from a different perspective, that of the names we use for our political groups.

We sometimes forget, I think, how extraordinarily durable and persistent the party structure in Britain is. The Conservative Party dates its foundation to 1834, based on the principles set out by Sir Robert Peel in the Tamworth Manifesto. In it, he accepted the changes of the Representation of the People Act 1832, otherwise known as the First or Great Reform Act. This reordered and regularised (to an extent) parliamentary constituencies, and broadened the property qualification to vote. But the new Conservative Party accepted it as a final settlement, and promised that other changes, such as in the Church of England, would be incremental and only implemented if they addressed real faults and grievances. The party was essentially the safety-first choice.

Even a party which celebrates its 190th birthday this December was not an innovation. Peel’s Conservative Party coalesced from the Tory Party, famously named for the Middle Irish word tóraidhe, which means “outlaw” or “robber”. The Tories had first emerged as a recognisable force in the Exclusion Crisis of 1679, when there had been an attempt to remove the King’s brother, James, Duke of York, from the succession on the grounds that he was a Roman Catholic. Tories had no time for Catholics, but they had a bone-deep belief in the social order and the privileges of birth and inheritance.

So the party which is in government in the United Kingdom at the present day can easily trace its lineage back 345 years. In 1912, they merged with, or rather absorbed, the Liberal Unionist Party, the group which had split from the Liberals in 1886 over Home Rule for Ireland, and formally assumed their current name, the Conservative and Unionist Party. From that merger in 1912 until the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, the party was frequently known simply as “Unionist”; and from 1912 until 1965, the Scottish wing of the Conservatives was officially the Unionist Party.

The Labour Party has a shorter history but still has many miles on the clock. The Labour Representation Committee was founded in 1900 as an alliance of socialist groups and trades unions, intended to co-ordinate the parliamentary representation of the Labour movement, and adopted the name “The Labour Party” in 1906. However, it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party, founded in Bradford in 1893 and affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932; in 1947, the ILP’s three remaining MPs joined the Labour Party and the organisation faded away in 1975. It is also not widely recognised that (currently) 27 Labour MPs are also members of the Co-operative Party, founded in 1917, and formally sit under the “Labour and Co-operative” label in the House of Commons. But Labour can look back to the earliest days of the Liberal Party endorsing some trades union-sponsored parliamentary candidates, with the first alliance generally held to be George Odger, a shoemaker who contested the Southwark by-election in February 1870 as a “Liberal-Labour” candidate.

The Liberal Democrats have a long but slightly tortuous heritage. They assumed their present identity in March 1988, when the Liberal Party and the Social Democratic Party (which had broken away from Labour in 1981) merged. Initially, the new entity was known as the Social and Liberal Democrats (which all too easily suggested “salad” to some wags), before shortening it to simply the Democrats in September 1988, before adopting the Liberal Democrat title in 1989. The Liberal Party, however, went back to 1859, when an alliance of Whigs, Radicals and free trade-supporting Peelites voted down the Earl of Derby’s Conservative government and Viscount Palmerston became prime minister. The Whigs, however, were the traditional counterparts to the Tories, again owing their name to an insult derived from “whiggamore”, a Northern English word for Scottish cattle drovers. The Whigs, like the Tories, emerged during the Exclusion Crisis: for them, the Duke of York’s Catholicism was the overriding jeopardy and they were willing to give Parliament a much freer hand in dictating the succession in order to preserve the Established Church of England.

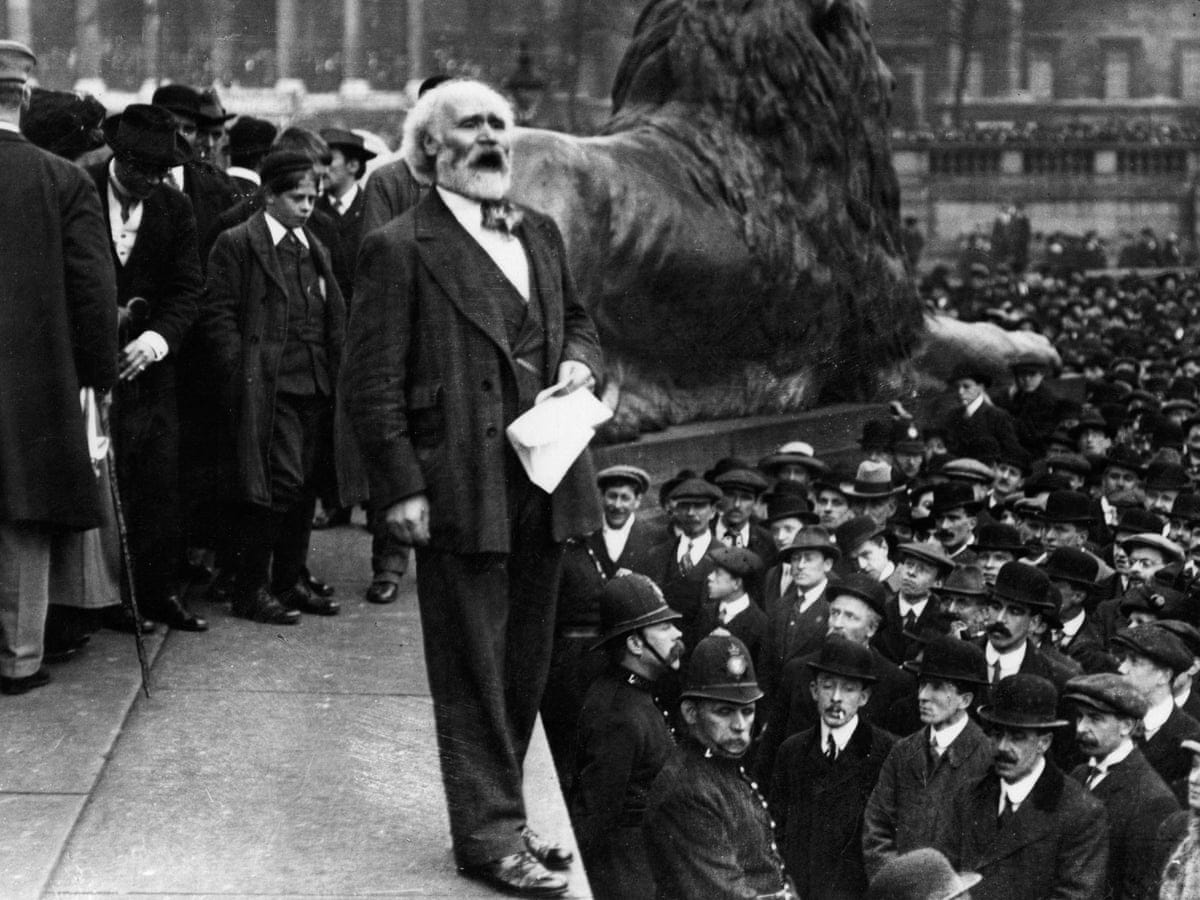

I dwell on the antiquity of our parties, partly because I think it is interesting, but also because it means that the major ideological groupings in our political system have names which are very old and in some cases coined in hugely different circumstances from those which obtain today. When the LRC was created in 1900, for example, contemporaries would have had a very clear sense of what was meant by “Labour”; its leading members included Keir Hardie, a coalminer from the Lanarkshire mines who turned to journalism; David Shackleton, a Lancashire cotton weaver; and Frederick Rogers, a bookbinder from Whitechapel. These were men who worked with their hands, and worked hard, whose formal education had been scanty (Rogers was no more than 10 when he left school), and who were active in the trades union movement.

Many other countries don’t have to consider this issue of heritage party labels. In the United States, admittedly, the Republican Party was founded in 1854 and the Democratic Party goes back to 1828, but the names are much less redolent of specific classes, groups or interests. Germany’s Social Democrats (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands) dates to 1875, with antecedents in the 1860s, and was one of the world’s first Marxist parties, but no other German political parties survived the trauma of the world wars.

In France, party labels and identities come and go very easily, groups cohering instead around two broad coalitions on the Left and the Right (although the party of the current president, Emmanuel Macron, was one of his own creation: he launched the centrist En Marche! in 2016, refining it to La République En Marche! and then to Renaissance in 2022). The current Socialist Party was only created in 1969, while the centre-right Gaullist instinct is now embodied by Les Républicains, reconstituted in 2015 from the Union for a Popular Movement, which had itself only come together in 2002 as the merger of a number of smaller parties under President Jacques Chirac. On the far Right, or populist Right if you prefer, Marine Le Pen created the National Rally in 2018 from the older, more extremist National Front founded in 1972 by her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen.

In Germany, as we saw, only the SPD survived from the days of Bismarck. The main centre-right party, the Christian Democratic Union, was established immediately after the war in 1945, mainly from former members of the Catholic Centre Party, Zentrum, as well as the liberal German Democratic Party, the German People’s Party and the nationalist, conservative German National People’s Party. The CDU’s more socially conservative Bavarian affiliate, the Christian Social Union, is regarded as the successor to the Weimar-era Bavarian People’s Party. Then in 1948 nine regional liberal parties came together to form the Free Democratic Party, which has been the main exponent of ordoliberalism, that peculiarly German form of economic liberalism which relies on the state to ensure that the free market produces the outcomes closest to its theoretical potential.

It is perhaps odd that, since Labour displaced the Liberals a century ago to form a new duopoly at the top of British politics, neither of our main parties has changed its name. In the 1930s, Neville Chamberlain, whose father Joseph had been one of the leaders of the Liberal Unionist Party and who had himself sat on Birmingham City Council as a Liberal Unionist in the 1910s, pressed the idea of renaming the Conservatives as the National Party, which he hoped would then bring in as many Liberals as possible in what would essentially be an anti-socialist group. In 1946, Winston Churchill, first elected as a Conservative in 1900 before defecting for many years to the Liberals, suggested they might become the Union Party, again principally as a vehicle to oppose socialism, but even as party leader, and with the support of the party chairman Lord Woolton, he made no headway. At the same time, Harold Macmillan, who had been a distinctly radical figure in the 1920s and 1930s, wrote an article in The Daily Telegraph in which he proposed they become the New Democratic Party, again in an anti-socialist alliance with the Liberals. The delegates at the party conference were clear that changing the name was not something on their agenda.

In fact, most of those engaged in the heavy lifting of transforming the party after its heavy defeat at the 1945 general election, like Rab Butler, chairman of the Conservative Research Department, and Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, who spoke principally on labour but also chaired a review of the party organisation in 1948-49, understood that there were more important changes to be made than a new name, instead streamlining the policy making apparatus, the finances and candidate selection. And the party’s swift return to power in 1951, after virtually wiping our Labour’s majority in 1950, suggested that the party’s name was not doing too much harm anyway.

Another seismic defeat in 1997, this one larger than in 1945, prompted more speculation about a change of name, though specific ideas were in short supply. The outgoing leader, John Major, addressing the party conference in Blackpool in October, sounded a note of caution. Although the party had to change, “we don’t need to re-write every policy. Or change our name.” The Scottish wing of the party, however, which had lost all of its seats at Westminster, considered rebranding as part of a wider programme of reform which would see it become semi-detached, its relationship with the UK-wide party like that of the CDU and the Bavarian CSU in Germany. Several potential titles for the party north of the border were mooted: the pre-1965 name of Scottish Unionist Party, the Scottish New Unionist Party (proposed by Malcolm Rifkind, who became president of the Scottish party in 1998), the Scottish Conservative Party, the Progressive Conservative Party, the Scottish Tory Party and the Scottish Democratic Conservative Party. I was at university in Scotland at the time, and also remember the suggestion of the Progressive Unionist Party; the fact that the name was already taken by the political front for the Ulster Volunteer Force, a loyalist paramilitary group, somehow seemed emblematic of the difficulties which selecting a new name could throw up.

In August 2004, a column by Mark Steyn in The Daily Telegraph asserted that the party was evaluating a name change if the following year’s general election went badly, and listed as potential options the Democrats, the New Democrats, Progress and the Reform Conservatives. After electoral progress had been modest, and the party sought to choose a fourth leader in opposition, Brendan O’Neill observed witheringly—what other tone would he use?—that “there is even talk of rebranding the Conservative Party as the Modern Conservative Party”. No formal proposal was ever put forward, but “the modern Conservative Party” was a phrase which Hague in particular had often used, and David Cameron would pick up as leader of the opposition in 2005-10.

Even after the Conservatives had returned to government in 2010, the notion of a rebranding to allow the party to reorientate itself or project a new image would not go away. In October 2015, after David Cameron had unexpectedly won a majority and been able to disengage from the coalition with the Liberal Democrats, Ian Birrell, a former speechwriter for Cameron, wrote in The Daily Telegraph that “the Conservative Party needs a new name”. The argument was as follows: Labour, by electing Jeremy Corbyn, were tacking far to the Left and vacating that prized, mystical centre ground of British politics; the “Conservative” brand retained an electoral toxicity and associations of entrenched privilege and wealth; selecting a new name would allow the creation of a new image embodying prosperity for all, devolution, workers’ and consumers’ rights and high-quality public services.

Birrell noted that Robert Halfon, the MP for Harlow who was at that point deputy chairman of the Conservative Party, had proposed becoming the Workers’ Party, though he dismissed that as “dated, like some tedious Trotskyite fringe group, as well as being unconvincing for the electorate”. He acknowledged the ideas of National, Progressive, Radical or Freedom Party, and added his own, the One Nation Party, “neatly linking past and present”. But he pointed to the example of France, where, as we have seen, the Gaullist UMP had rebranded as Les Républicains.

Birrell was unlucky in his timing. Within a year of writing his article, David Cameron would be gone, a casualty of the Brexit referendum, and within two, the presidential candidate of Les Républicains, François Fillon, had been knocked out of the poll in the first round and the party had lost nearly half its seats in the National Assembly. Meanwhile the supposedly hopeless Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, had performed surprisingly strongly at the snap general election in June 2017, robbing the new prime minister, Theresa May, of the slender majority she had inherited from Cameron. It was not a ringing endorsement for rebranding.

The idea that a name change will unlock huge electoral benefits persists. Last spring, rumours surfaced that Isaac Levido, the Australian political strategist advising Rishi Sunak, was, like so many before him, concerned by the alleged stigma attached to the Conservative brand and was examining alternatives, including the Patriotic Party. But the issue has faded again, perhaps as people realise that, while the party faces an enormous challenge and is likely heading towards a savage and humbling defeat, it cannot simply be ascribed to the name.

The Labour Party has arguably undergone even more severe existential crises over the past century or more. While Labour overtook the Liberals to become one the two major parties on 1923, it split badly in 1931 when the small group of Labour MPs who followed prime minister Ramsay MacDonald in forming the coalition National government were repudiated by the bulk of their colleagues. At the general election that year, the Labour vote collapsed, and they were reduced to just 52 seats (second behind the Conservatives who an almost unbelievable 470), and although they recovered some ground in 1935, they were left with only 154 MPs.

Yet there has never been a serious move to change the party’s name. Perhaps this stems in part from its more legalistic nature: the very first provision in the party’s rule book, under Clause I: Name and objects, reads “This organisation shall be known as ‘The Labour Party’ (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Party’).” In the 1950s, as the party lost three elections in a row so soon after the heady days of the 1945 landslide, there was some introspection. Douglas Jay, MP for Battersea North, who had been a junior Treasury minister under Clement Attlee, wrote an article in Forward eight days after the party’s 1959 defeat. He identified the danger of relying on emotional ties between fading heavy industry, increasingly prosperous voters and the Labour Party in its traditional form, and argued that it must reposition itself as a “vigorous, radical, open-minded Party” free from traditional ties of social class. A signal of this change, he proposed, could be a new name, and Jay suggested “Labour and Radical” or “Labour and Reform”.

There was a recognition that the debates within the party in the late 1950s and early 1960s had more fundamental issues than the party’s name. Alternatives tended to be provided by those who left the party, unable to countenance membership any longer. When Dick Taverne was deselected by his constituency Labour Party in 1972, he left and formed the Lincoln Democratic Labour Association and resigned from the House of Commons to force a by-election. He was re-elected in the March 1973 contest under the Democratic Labour label, overwhelmingly defeating the official Labour Party candidate, and held on narrowly at the general election in February 1974, then losing in that year’s second election by 984 votes to Labour’s Margaret Jackson, later Beckett.

Taverne also formed a group called the Campaign for Social Democracy, a radical party which was social democratic rather than doctrinaire and socialist, and intended to oppose the hard Left MPs of the Labour Party. It made no electoral headway, but it is significant that when the “Gang of Four”—Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams—left the Labour Party in 1981 in protest at the increasing influence of the Left, the vehicle they created was initially called the Council for Social Democracy. This quickly transformed into the Social Democratic Party (SDP) which, for a short time in the early 1980s, looked more likely than anything for generations to break the mould of British politics.

The emergence and early success of the SDP, which in June 1981 united with the existing third party to form the SDP-Liberal Alliance, took their toll on the Labour Party. At the end of 1980, its MPs had narrowly chosen Michael Foot, courtly, learned and ageing, as the new leader over Denis Healey, easily the biggest beast in the Labour jungle. Foot was far to the Left of his opponent, and the departure of so many moderates to the new SDP left Labour more extreme than ever. At the 1983 general election, the party would win only 209 seats, its manifesto famously described by Gerald Kaufman as “the longest suicide note in history”. Worse, it secured only 28 per cent of the vote, its worst performance since 1918.

The autumn after the election, Welsh MP Neil Kinnock, who had been shadow education secretary from 1979 to 1983 but crucially had not held office in the previous Labour government, was elected party leader. For nearly nine years he would undertake the transformation of the party, and the eventual success of the process owed much to him, but it was a bitter disappointment for Labour when John Major snatched victory for the Conservatives in 1992 and Kinnock retired. For all that Kinnock and his ill-fated successor, John Smith, had to remake in the Labour Party, a formal rebranding never seemed to come close to the top of the agenda. However, a rebranding exercise would take place, it would be overwhelming and it would be successful, but it was never official.

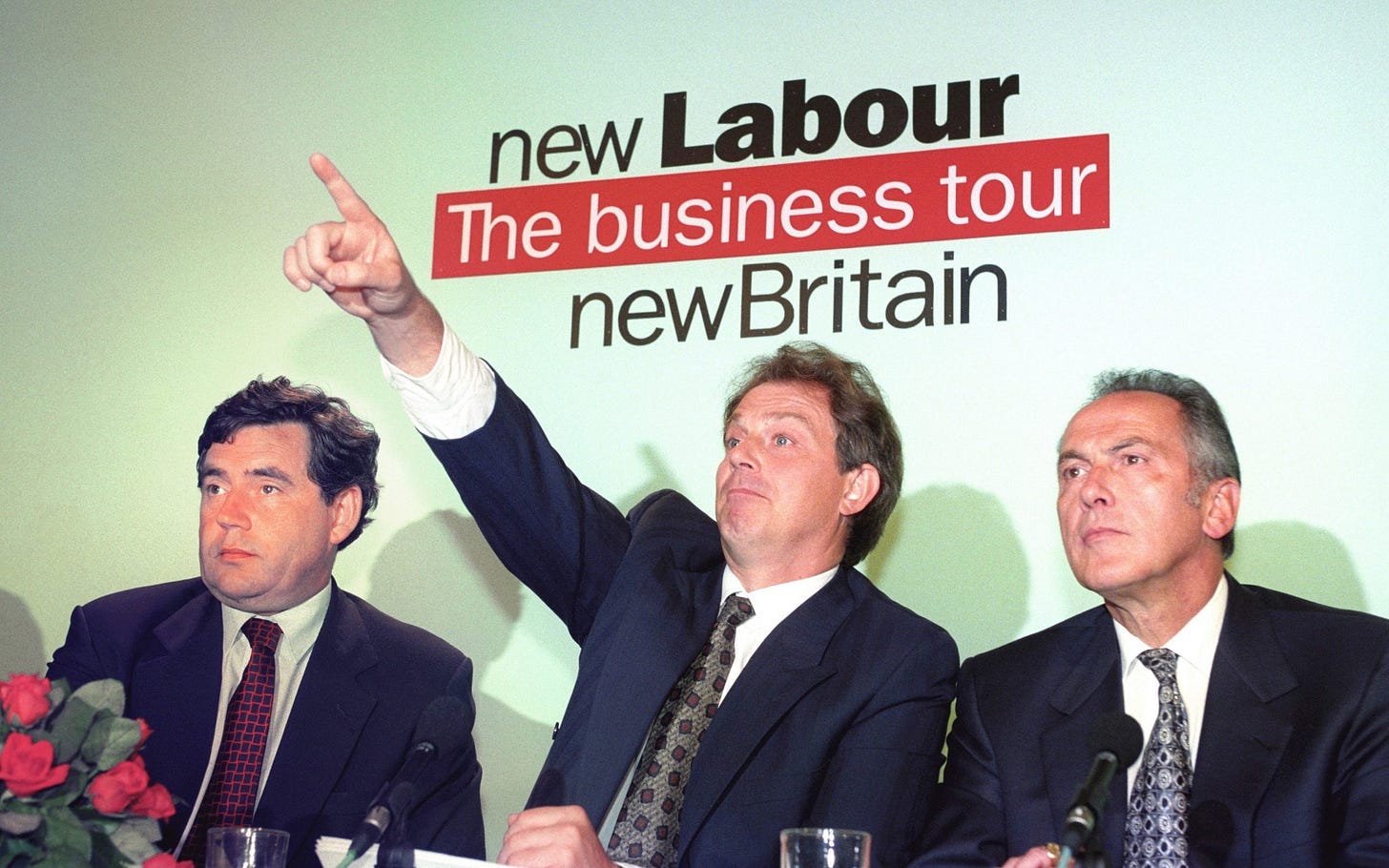

After the sudden death of John Smith in 1994, Tony Blair, previously shadow home secretary, was elected leader, with bluff, experienced trades unionist John Prescott as his deputy. Blair had been thinking about the modernisation of the party for years, and shortly after he became leader he introduced a bewilderingly simple but devastatingly effective rebrand. When he addressed the party conference in Blackpool in October 1994, he used as a fundamental and recurring motif the idea of “New Labour”. Indeed, it appeared 37 times in his 62-minute speech, while the conference more broadly was dominated by the slogan “New Labour, New Britain”.

The “New Labour” formulation would become crushingly universal, and it drove Blair’s opponents—inside the party and outwith—to paroxysms of rage, but it was a masterstroke. Not only did it sum up the whole ethos of his leadership, renewing Labour and therefore (it implied) making it better, more relevant and more popular, but it also forced his critics into an “Old Labour” identity. And it did all this without the soul-searching of a formal rebranding, because it was, in essence, just a slogan. Many expected that Blair would go on to seek to change the party name, but at the special conference in April 1995 at which he secured the approval of a revised Clause IV of the party’s rule book, he confounded his opponents again. While Martin Kettle had written apocalyptically in The Guardian before the conference voted that “What we shall see this afternoon is the collapse of Labour as the party of organised labour”, Blair announced that the Labour Party would not change its name—but of course “New Labour” would remain one of the most ubiquitous and effective acts of political branding in generations. Yet he announced to the media, “Today a new Labour party is being born”.

So we have a political system reliant on two parties which are of very long standing, with accordingly long, entrenched and cherished traditions, and names—brands, if you like—which have not changed significantly in more than a century. Look at the general election of December 1923 which would usher in the country’s first socialist government. The largest party was the Conservative and Unionist Party, with the Labour Party in second place and the Liberals trailing in third. Sound familiar?

By comparison, look at the French legislative election in May 1924. Topping the poll was the Democratic and Republican Union, followed by the French Section of the Workers’ International, the Radical Socialist Party and the Republican-Socialist Party. None exists in that form today. Germany went to the polls the same month, and the Reichstag was dominated by the Social Democrats, the German National People’s Party, the Centre Party and the Communists. Only the SPD survives in today’s Bundestag.

Does this matter? I think it does, because the marketplace of democracy is an imperfect one. Each of us may take a bespoke set of ideologies, beliefs and traditions to the polling booth, but there is a strictly limited number of suppliers. I wrote recently in The Critic that political parties are necessarily broad churches, and we understand that we are choosing a best fit rather than something tailored perfectly to us. But a kind of feedback loop exists, and we are shaped by our allegiances as well as shaping the parties to which we owe that allegiance. And this is potentiated by the kinds of names our parties have in the UK.

We’re all familiar with the incantation of “small-c” and “big-C”, but to say that you are a conservative or a Conservative still means something, something more than simply adherence to a current policy platform of a political party. There are attitudes inherent in that response, or at least others can be forgiven for discerning them. Equally, to say that you are Labour comes with a long tail of emotional and historical resonance. You are positioning yourself in a narrative which includes, yes, the bright optimism of the Blair government, but also Harold Wilson’s white heat of technology, the New Jerusalem dogged optimism of the post-war Attlee government and the great expressions of mass working-class identity and interests; you are underneath the banners of the earnest and hungry Jarrow marchers, the solidarity of the Durham Miners’ Gala and the desperate, simmering stand-off of the Tonypandy riots.

While these ideological garments might seem ever more ill-fitting in the 21st century, further divorced than ever from the challenges and circumstances we face as citizens today, at the same time they can be invoked, with varying degrees of subtly, as purity tests. How often do we here Sir Keir Starmer dismissed by opponents on the Left as “literally the new Tory party”, “almost identical to the Tories” or “an actual Tory enabler”?

On the other side the same kind of tests are applied. The government consists of “liars, cheats.. who aren’t really Conservative”, the prime minister is “a globalist… we need a real Conservative party” and “wouldn’t know what a Conservative is”. This increasing habit by elements of the Right annoys me, as I dislike being told what I think and why I think it, as I wrote in December. But it’s also a nonsense, blinkered, ignorant and ahistorical. The identities of parties are broad and they change over time, especially if your parties have hundred miles on the clock.

It is perfectly possible, and would have had some force in 1975, to argue that Margaret Thatcher was “not a real Conservative”. She was in many ways a Manchester liberal, her economics from the Austrian school via Chicago, but set in wider framework which simply wouldn’t have existed without the profound influence of provincial English non-conformism from her Methodist upbringing in Grantham. Her opponents, who had created the post-war settlement with its reverence for full employment, its persistent belief in the necessity of state intervention and the spirit of Butskellism, certainly felt that she represented an aberration from the Tory faith. They were neither wholly right nor wholly mistaken, but she took them on and won, and that allowed her to change the ideological landscape, to redefine what “being a Conservative” really meant.

I don’t pretend to know where we go from here. If a brave government did change our electoral system—something I’m not in favour of, and don’t think especially likely, but it is certainly possible—the multi-party milieu which proportional representation can support might well see our fissiparous parties splinter: we could see a socialist party, a social-democratic party, a free-market libertarian group, a socially conservative nationalist party, perhaps an openly racist far-right party or an unashamedly communist grouping.

If we don’t see change that radical, there are still serious debates within parties which will have to take place. Although Starmer’s prospects of electoral success will shield him for the moment, there are some who now so wholly and emphatically reject capitalism that they may not be able to tolerate life within a mainstream Labour Party for ever. The Conservative Party’s radical bifurcation of instincts between free marketeers and small-government conservatives on the one hand and protectionist, communitarian conservatives on the other is not inevitably sustainable. And the red lines, the issues on which there can be no compromise, are shifting all the time. The UK has no real tradition of a powerful religious right, of the kind which has flourished in America since the 1970s, but that may not last for ever: at the National Conservatism conference in London last May, Danny Kruger, Conservative MP for Devizes, declared that marriage between a man and woman was “the only basis for a safe and successful society”. His colleague Miriam Cates, MP for Penistone and Stockbridge, told a Christian publication that a loss of faith had done society a great deal of harm:

I think there’s certainly a quest for meaning. We have more stuff than we’ve ever had before, especially in the West. Yet people are more despairing, we have more mental health problems, suicide is now the number one killer of men under 50. We’ve got all this stuff, but we have no meaning, no purpose; we’re not happy.

At the same time, it is starting to seem impossible to avoid a frank and painful national conversation about integration, multiculturalism, immigration, race relations and the desirability—indeed, feasability—of any sense of shared national values.

It is a commonplace that membership of political parties, notwithstanding the substantial uptick the Labour Party experienced before and during Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, has collapsed within a couple of generations. It is now a very niche activity: available figures suggest maybe only a million of us are members of any party at all, while, to take one body at random, the National Trust has around 5.7 million members. Yet we still do our politics through parties, and that is unlikely to change.

Long-established parties with small, unrepresentative membership, thick accretions of ideology and tradition and a lurch towards intolerant, factional conceptions of loyalty and fidelity: these are massive challenges which are already affecting the way our governments govern and our relationships with our political leaders. What I can say with certainty is that this is not over. The challenges continue and develop, and they will not go unattended forever. I hope that we will, in the fulness of time, recognise that the best way to surmount them is by learning, remembering, talking and listening.

Many people in Australia find it odd that 'optional preferential' voting is not permitted in the UK and more widely.

Have you any objections to it?

I am part of a small minority who think that people should have a possibility of voting for 'no candidate' -- so that if 'no candidate' is elected, the seat remains vacant for a year.

Any thoughts?