Don't tell me what I think or why I think it

The right of the Conservative Party is acting more and more dismissively towards those who disagree with it; for all our sakes, this has to stop now

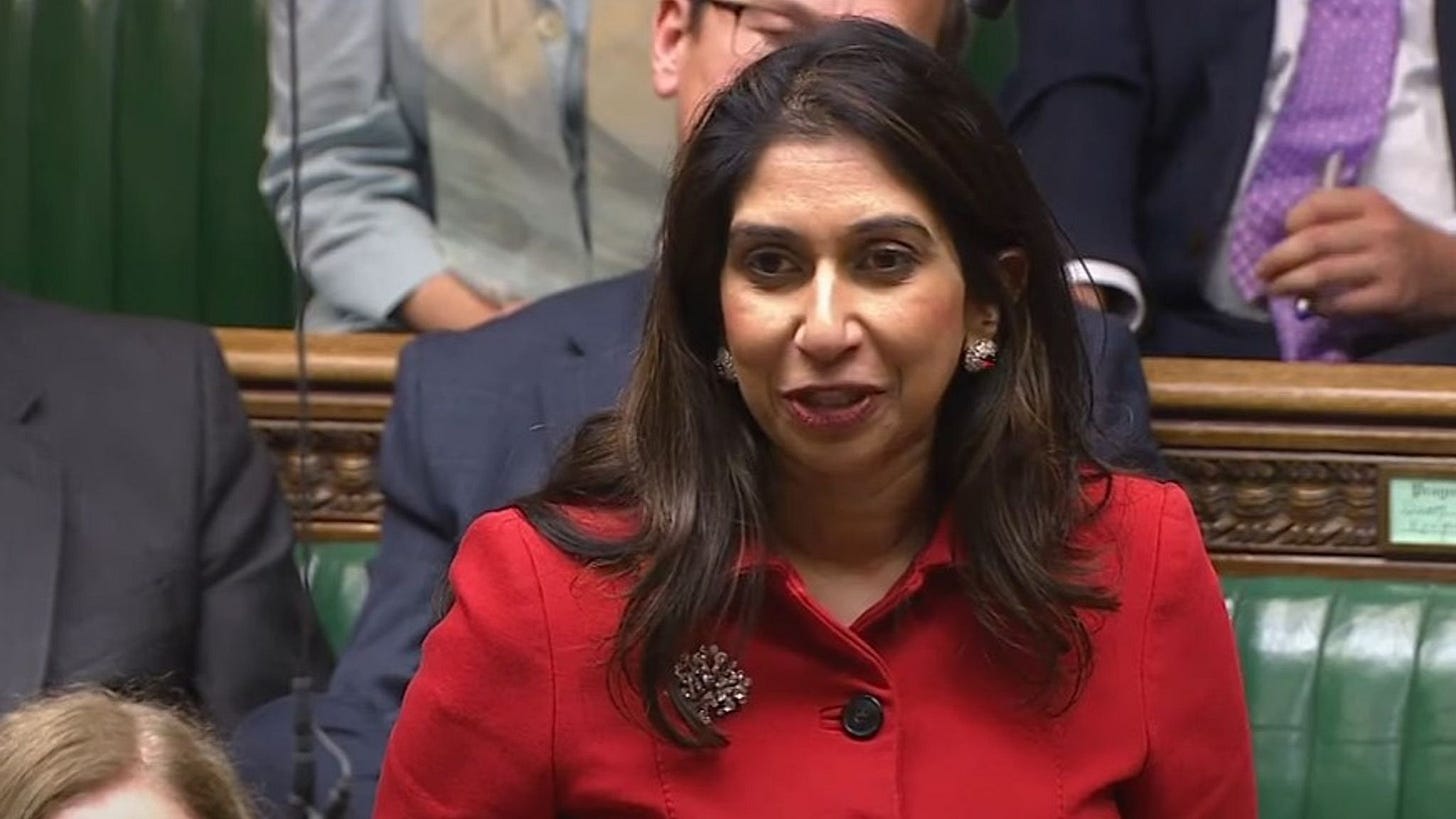

It would be hard to argue that Wednesday was a good day for the Conservative Party. Suella Braverman gave her “resignation” speech (she was dismissed as home secretary, as sharper readers will recall) and wailed about “electoral oblivion” if the government didn’t adhere precisely to her unproven, unlawful and misguided policy on migration. The Home Office published the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill, a short-ish measure which was bold in reaching for statute to reorder reality but seems to have plotted an extraordinary passage which means it pleases none of its potenial critics. And to crown the day, the immigration minister, Robert Jenrick, decided he could no longer support government policy on, you guessed, immigration or in all good conscience steer the bill through the House of Commons, so promptly resigned.

It is, however, much worse than that. Discipline is eroding fast within the party, but, even more important than that, mutual tolerance is disappearing. The right of the Conservative Party, in particular, can now barely tolerate those who disagree with it. Allister Heath’s broadside in the The Daily Telegraph was barbed but he is not alone.

“The Tory Left-wing caucus is too large, too petulant, too intent on political hara-kiri: it was prepared to veto any genuinely novel thinking.” That was his sweeping starter for 10, but it was simply a starter. He continued that “too many Conservative politicians”, by which he means those who don’t agree with his argument, “dislike their own voters”, and portrayed an electorate “enraged by the Government’s betrayal of their values and interests”.

Heath cannot or will not accept that anyone could have a different point of view which they have reached calmly, soberly and rationally. Instead they are “embarrassed by the suburban attitudes, the quiet patriotism and the cultural conservatism of Tory Britain”. They find “Right-leaning Middle England” mortifying and “cringeworthy”. Why is this? It is a gruesome, crawling, dishonourable desperation to be liked:.

These renegade MPs suck up to outlets such as the BBC, better to relate to their dinner-party companions, who tend to be other members of the new, “high-status” ruling class. They spend much of their time on Twitter, or if young enough, on TikTok, lapping up nonsense. They are hooked on Left-wing podcasts that reinforce their insularity, their sense of comradeship with “rival” politicians and lull them into believing that their progressive views—often held by just 10-30 per cent of the electorate, almost none of whom vote Tory—are the mainstream and everybody else are extremists.

This is extraordinary venom from a right-wing journalist. In passing, I never thought that dinner parties would become objects of derision in a significant section of the Conservative Party. Presumably these gatherings are qualitatively different from the £1,400 lunch Liz Truss hosted for the US Trade Representative at private members’ club 5 Hertford Street in 2021 (which, by the way, I wholly supported: ministers absoloutely should be good hosts to influential allies and guests). I wonder what Heath would have made of the Conservative chief whip, Captain David Margesson, who kept a table at the Mirabelle on Curzon Street every day when the House was sitting; Chamberlain’s legendary disciplinarian would have blinked at being described as “Left-leaning” or “defeatist”, let alone sympathetic to “wokery”.

It isn’t just Heath. Patrick O’Flynn, stretching his rhetorical legs in The Spectator, tears into the “patrician liberal wing of upper-class internationalists” in the Conservative Party, saving his adoration for the “earthier, more provincial pro-nation state party that is genuinely socially conservative, particularly around the totemic issue of border control”. But O’Flynn knows that history is on his side. “Blue Wall, Home Counties Tory liberalism” is destined to be crushed and will “become so much political roadkill”. Nile Gardiner, a former aide to Margaret Thatcher, is on the same page. Braverman’s statement in the Commons resulted in “Lefties in meltdown”, “there is a refusal to fully restore British sovereignty from the EU” and “Britain’s Conservatives would be in a far better position today if they were still led by an actual conservative, like Liz Truss”.

It is worth pausing for a moment to reflect that the immediate casus belli, the policy of diverting asylum seekers from the English Channel to Rwanda to be assessed and dealt with, is a red herring. I explained yesterday that, even if we accept the policy as wholly legal and compliant with every treaty and agreement, it has no evidential basis for its effectiveness or value for money, and, even if we were to accept that it would be wholly effective, it is directed at a group of would-be migrants which last year numbered 37,556, while legal migration, on which the Rwanda plan would have no effect, amounted to 672,000 people. To place the cherry on the cake, the latest polling shows that half of those who were asked thought the policy would not achieve its fundamental aim of deterring people from trying to cross the Channel in small boats. Such is the hill on which we fight.

This much, however, is all good, clean, political fun. Politicians can disagree on priorities, objectives, methods and likelihood of success, and they can do so across the floor of the House or within parties. That is normal and healthy and the everyday cut-and-thrust of our public life. The right is taking it further: it is snatching the methodology more familiar on the far left, establishing one course of righteousness and truth, and determining that those who do not follow that course are malign, obstinately heterodox and blinded by the basest of motives. And that, that I will not have.

I think the Rwanda plan stinks. It was devised by Boris Johnson and Priti Patel, neither of them strategic powerhouses, but I am happy to suppose for the moment that they drew up the scheme to put a huge dent in the number of migrants arriving in small boats. They chose a strange totem, given that illegal migration is absolutely dwarfed by legal migration, and that by definition control of the latter if entirely within our hands whereas the former brings into play other jurisdictions, treaties and international agreements. Patel in particular clung stubbornly to the policy: when her permanent secretary, Sir Matthew Rycroft, told her that, in his capacity as principal accounting officer for the Home Office, he did not have enough evidence to say that the policy represented good value for money, she issued, at his request, a ministerial direction instructing him to press ahead with the plan. It is an amazing document which privileges confidence and optimism over even the possibility of evidential assessment.

There were long-standing flaws in the Rwanda policy. My friend and former colleague Alexander Horne, a former senior legal adviser in both Houses of Parliament, has explained eloquently why the Supreme Court ruled the plan unlawful and examined the prime minister’s plans to revive it; I have previously argued that the court’s verdict gave Sunak, who had not created the scheme, the opportunity to shake his head sadly and walk away to devise a new approach, rather than—as he has chosen to do—double down and seek a confrontation with some of his own backbenchers, the House of Lords, perhaps the UK judiciary and maybe the ECHR too. I think there is a small number of proponents of the Rwanda policy who see it as a declaration of intent, a wedge issue to use against the Labour Party in the forthcoming election campaign and, more generally, a kind of symbol of political machismo: see how much we want to control our borders! See the lengths we will go to! But I’m quite happy to accept that most of the plan’s supporters are, firstly, genuinely concerned by the number of illegal migrants arriving in the UK, and, secondly, anxious that sustained failure to reduce the numbers of these migrants sends a message to the world that the UK is a soft touch in more general ways. I disagree, and I’ll happily explain why, and I’ll listen to every argument you have in the other direction. We both want a well-ordered and well-managed state, so let’s exchange views.

Let me be very clear about something: I love arguing. I meant that it a very specific way. I say “arguing” rather than “debating” because, having done a lot of it at university, I tend to think of debating as a formalised process, but choose your own word. What I mean is, I relish sitting down with other intelligent people, passing round the relaxant of choice (alas I gave up booze more than five years ago but I’m very happy for others to indulge as much as they like) and talking about big ideas, world views, approaches to problems, ways of trying to make the world we all share a little better for everyone. I have friends from across the political spectrum, friends whose opinions have endured for decades and some whose way of thinking has evolved as time goes by. In some cases, we know we will never agree nor will either convert the other: one of my dearest friends is a passionate Remainer, for whom association with the European Union is both a matter of practical policy but also a matter of deep emotional significance, but we can talk about it, explain why we think as we do, think, in all charity, that the other is wrong or at least misguided, or simply that we reach different conclusions from the same evidence base. And voices will be raised but tempers do not flare, because we respect each other. It’s basic but it’s vital.

I say all of this because a fellow Conservative (or even simply conservative) could take a different view from mine on almost every major policy issue but if he or she was willing to interact, to exchange views, then that will command my respect automatically. Very few people are genuinely of malign intent. Most people want the best for most other people. So don’t assume you know why your opponents think the way they think, certainly don’t assume that they are malign and absolutely do not tell them they are malign when they try to explain their reasoning. That is not argumentation: that is smear and cowardice.

This assumption of ill intent, a search for doctrinal purity, an obedience to an assumed “will of the people”, accusations of fraternising with the enemy or even frankly political Nicodemism, of hiding true beliefs under the mask of false ones, has to stop. If Suella Braverman thinks the Rwanda policy offers the Conservative Party “electoral oblivion”, she would do well to wonder how the voters will judge a party which could start a fight in an empty room, which is scrapping internally with no Marquess of Queensberry rules, and in which every opponent is an enemy. We’ve seen this before, in the late-stage Major government in 1996/97, in the Callaghan administration of 1978/79, in the crumbling MacDonald ministry as the economic crisis deepened in 1931, and we know what happens: the electorate thanks you for your interest in the post of “responsible government” but has decided to go with someone else.

This last issue is one of genuinely strong feeling. If you tell me what I think, or why I think it, I will find it annoying, and I will push back hard. But I absolutely will not be told whether my views are or are not “conservative” or within the ambit of the Conservative and Unionist Party. This is doubly, triply true if you’re under the age of 30 or so. I was discussing this earlier with a few people, inside the party as well as without.

I was born a Tory, I am a Tory and shall die a Tory: it is part of me, an inborn way of apprehending human life and society and the history and character of my own country. It is something I cannot alter.

It was Enoch Powell who said this, in a speech in Shipley in February 1974 after he had abandoned his membership of the Conservative Party and advised the electorate to vote Labour. (A heckler shouted “Judas!” The atmosphere was electric as Powell stopped his speech and pointed. “Judas was paid! Judas was paid! I am making a sacrifice.”) Powell got much wrong and sometimes acted in malign ways, but I am happy to borrow the words above from him to describe my own political identity. Interestingly, given the comparison between the two men, Powell’s words also call to mind something Rory Stewart wrote in his recent memoir, Politics on the Edge.

If forced to spell out a political philosophy, I would have said that I believed in limited government and individual rights; prudence at home and strength abroad; respect for tradition, and love of my country. In short, as a fellow academic who was applying to be a Labour MP observed, I was perhaps if not a Conservative, then at least a Tory.

I have a lot of sympathy with Rory’s view too, and certainly wouldn’t resile from any of those propositions. But Conservatives, and indeed conservatives, come in a variety of shapes and sizes. I would have found myself very uncomfortable with the way the governments of 1951-64, let alone 1970-74, managed the economy. I regard Macmillan with a slightly guilty sense of affection, for all that he was a terrible old ham and a shameless deceiver, while Heath sends a shiver down my spine and I recoil at his unremitting self-confidence and inability to admit fault: but I don’t dispute that both were Conservatives. (Macmillan in fact chafed against the party: he had peered curiously at Sir Oswald Mosley’s New Party during its brief existence in 1931-32, had links to the progressive Next Five Years Group later in the 1930s, proposed changing the name of the Conservatives to the New Democratic Party in the late 1940s and admitted he was “not a very good Tory”.)

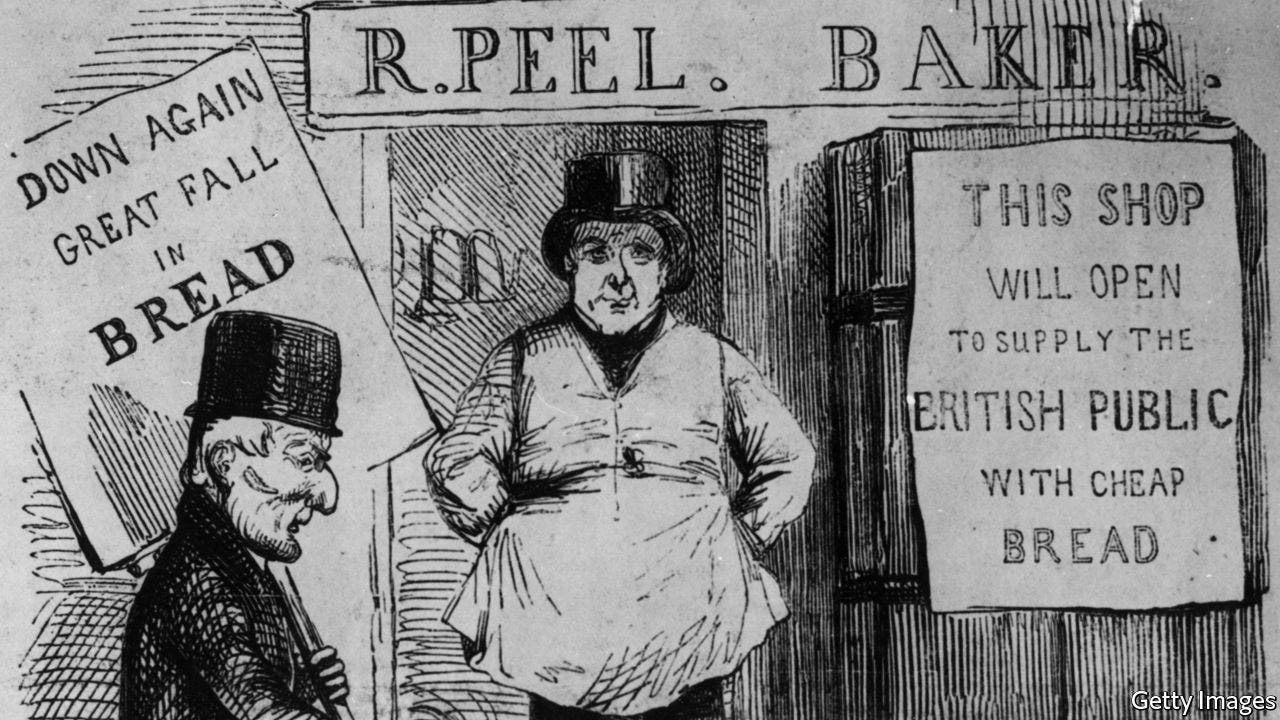

Equally, over the decades and centuries, the Conservative Party’s official views, or at least the preponderance of them within the party, has changed. In 1846, Sir Robert Peel put the party more or less out of office for a generation when he embraced free trade and repealed the protectionist Corn Laws with the Importation Act 1846. But free trade was not thereafter a settled policy. Protectionism gained the ascendancy during the 1860s, but Disraeli resisted its implementation in the 1870s and free trade was the received wisdom until Joseph Chamberlain tossed the hand grenade of tariff reform into the Balfour government. Bonar Law and Baldwin were protectionist by instinct, as were Austen and Neville Chamberlain, and free trade would not be a significant policy until after the Second World War, and, in Conservative circles, after the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1975.

I am absolutely a free trader. One of my dissatisfactions with the European Union was that, for all the glories of the Single Europe Act, Europe practised free trade within its borders but had, and has, stiffly protectionist attitudes to the outside world. This was demonstrated in September when a row loomed over tariffs on batteries for electric vehicles. I have the same foundational view of trade as I have of most human interactions: leave people alone to get on with their legitimate business, whatever that may be. But I am aware that free trade does not rule the right-wing roost quite as it used to. Donald Trump queered the pitch for that as for so many things by seeing tariffs as a status symbol as well as a handy weapon in his cold-but-warming war with China (notwithstanding his teenage crush on President Xi, reminiscent of the breathless affection he seems to feel for most autocrats and dictators). Free trade seems to have the upper hand in the current Conservative Party—Boris Johnson’s conception of a post-Brexit world would have made little sense without it—but I am always aware that patterns can shift, opinion can move.

I am prickly when Brexiteers chide me for something less than full accordance with whatever new policy they have devised. I voted Leave, I would vote Leave again, and I would always have voted Leave. It may be a rather sad reflection on me, but this was something I thought deeply about when I was at university; my first attempt at undergraduacy, in Oxford, coincided with the aftermath of the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty (or rather, the Treaty on European Union), when our relationship with Europe was a subject of fierce debate. In those days (I went up in October 1994), not every Eurosceptic wanted to withdraw from the EU completely, and many who did regarded it as a dream, something with which they could tantalise themselves on a torpid summer afternoon in a standing committee, but not likely to be achieved. I shared that view, and thought relatively little about a United Kingdom outside what had just become the European Union; but I knew too that, if I took thought processes to logical conclusions and applied the rigour I was having to learn as a struggling classicist in fully mastering Latin and ancient Greek to my political views, my objections to the EU—essentially focused on sovereignty—could only lead to one destination: out.

That made my choice in the referendum in 2016 easier than some people’s, I imagine. And I really feel for those who were conflicted. It was the biggest decision some of us will ever make, certainly at the ballot box, and no matter how well-informed you are, no matter how intelligent, no matter how much thought you devote to the process, reaching a final decision was tough for many. That it was relatively simple for me certainly doesn’t suggest some advantage or superiority on my part.

Nevertheless, I am not stupid. I have educational and professional evidence to suggest I am, in fact, reasonably bright, able to solve problems and think through complicated processes, and maintain a systematic and logical approach to intellectual issues. I understand what sovereignty means, I understand the notion of parliamentary sovereignty and of the Crown-in-Parliament, and I know how we got to our current constitutional arrangements. So if I disagree with you on an issue in this area, at least grant me that it may not be due to a lack of capacity to understand or a lack of familiarity with the ideas and institutions.

Let me bring us back to the Safety of Rwanda Bill. Mark Francois, chairman of the European Research Group, warned yesterday that his claque would not support proposed legislation which does not “fully respect the sovereignty of Parliament, with unambiguous wording”. Gently, and I say this perfectly prepared to be contradicted, I think he is being careless with language. What he seeks to do, I think, is have a bill which says that there shall be no interference from any outside body (he is presumably thinking of the ECHR) in the process of sending asylum seekers to Rwanda; that is the sense in which he means the bill must “fully respect the sovereignty of Parliament”. I take a slightly different view. While I have moved a little on this in recent weeks, I do not think we should withdraw from the ECHR, not derogate from all its terms; but Parliament can exercise its sovereignty in acknowledging in one piece of legislation that we have obligations elsewhere. And these obligations were not imposed upon us: the UK government freely signed up to the convention in November 1950; moreover, it was a British Conservative lawyer, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, who chaired the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe’s Committee on Legal and Administrative Questions which drafted the terms of the convention, drawing heavily on a draft produced by the European Movement, itself with a British president, Duncan Sandys.

(Maxwell Fyfe is a fascinating figure. Briefly attorney general in Churchill’s caretaker government of May to July 1945, he was then the British deputy prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg but in fact managed the UK side of the trial day-to-day while his successor as attorney general, Sir Hartley Shawcross, attended to his political and parliamentary duties in London. His cross-examination of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, not an area in which he traditionally excelled, was a masterpiece. He went on to be a conservative home secretary in 1951-54, then served as lord chancellor from 1954 to 1962, when he was dismissed by Macmillan in the Night of the Long Knives. Maxwell Fyfe, by then Viscount Kilmuir, complained that he was let go with less notice than a cook. Macmillan observed that it was more difficult to find a good cook than a good lord chancellor.)

So I don’t think that this rather miserable Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill is in some way representative of unfulfilled parliamentary sovereignty. I believe absolutely Parliament is sovereign, and, although I would not have chosen this way to demonstrate it, I think the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty is so powerful that it can, legally, declare that where Rwanda was not safe before, it is now safe. Parliament can wave that statutory wand, and as far as the law is concerned it is so. Equally, Parliament could make an act which said that the sun orbited the earth. In law, that would be so. It would not, however, affect reality. The earth would still go round the sun, and I fear that Rwanda may still not be a wholly safe place to send asylum seekers.

I realise that I have battered this argument to death, flogged a horse well past its final moments and beyond even a period for which its friends are sitting shiva. But this whole matter of respect and acceptance of different is vital. We must, not just as Conservatives but as citizens in a mature democracy, allow each other to have our own beliefs, and it is no more than manners to assume that, unless there is obvious proof to the contrary, our intellectual opponents differ from us because of the thought processes they have used and the differing order of priorities they might have. WE cannot assume that they are knaves and fools. That is simply a gigantic exercise in poisoning the well of public discourse from which we all have to drink. It is arrogant, aggressive, corrosive, insulting and unproductive.

So, as we face another day, pause for a moment. Think. And if you’ve been expressing yourself in the terms exemplified by Heath, O’Flynn and Gardiner (as a mere selection) mentioned above, behave yourself. As they say in the deliciously punchy and expressive language of Northern Ireland, a place I adore, wind your neck in. Act with respect, and you’ll receive it in return. And we all might just get out of this alive.

Eliot, does it not bother you that, under the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, Parliament could legally take way any or all rights of UK citizens (e.g. access to the courts, trial by jury, freedom of speech) and the UK courts would be powerless to intervene?