Is Rwanda decision-time for the House of Lords?

The prime minister will soon unveil legislation to override the Supreme Court's judgement that sending asylum seekers to Rwanda was unlawful

[Note: I don’t always list post-nominal letters, however much they fascinate me, but as this is an essay dealing in particular with legislation, appeal and statutory interpretation, I have used KC for King’s Counsel where appropriate.]

To an extent, this story begins on 15 November, just a few weeks ago, when the UK Supreme Court ruled that the government’s plans to divert people seeking asylum in the UK, or potential illegal immigrants, to Rwanda. In a unanimous judgement, the court found that those sent to Rwanda might be subject to repatriation and then in danger of persecution, a process known legally as “refoulement”, that human rights in Rwanda were often infringed and that the asylum process in Rwanda was not robust. The policy would also have contravened the UK’s international agreements such as the European Convention on Human Rights, but Lord Reed of Allermuir KC, the president of the Supreme Court, pointed out that contravention of those agreements was not the sole or determining factor in the court’s judgement.

Rishi Sunak’s reaction to the Rwanda policy being declared unlawful was to double down and announce that ways would be found to override or circumvent the judgement. I wrote shortly afterwards that this was a mistake: the policy was devised by Boris Johnson and former home secretary Dame Priti Patel, and was always a statement of intent rather than an effective measure based on empirical evidence. Moreover, only two days before the judgement was delivered, Sunak had rid himself of his own turbulent priest, Suella Braverman KC, and in sending James Cleverly, a charming, persuasive figure, to the Home Office to replace her, he had, or could have had, rolled the pitch for a pragmatic change of course.

That did not happen. So new legislation it is to be, and this legislation will be read alongside a new treaty between the UK and Rwanda, signed in Kigali on 5 December, which seeks to address several of the criticisms contained in the Supreme Court judgement. It is worth saying at this point that treaties are a slightly complex part of our constitutional arrangements: they are signed by ministers on behalf of the sovereign and therefore under the Royal Prerogative, but, under provisions in the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010, draft treaties must be laid before the House of Commons for 21 sitting days, accompanied by an explanatory memorandum “explaining the provisions of the treaty, the reasons for Her [sic] Majesty’s Government seeking ratification of the treaty, and such other matters as the Minister considers appropriate”. However, that provision simply codified the Ponsonby Rule of 1924 and provides no explicit mechanism for scrutiny or rejection of a draft treaty.

The House of Lords has an International Agreements Committee, chaired by the former attorney general Lord Goldsmith KC, which also scrutinises draft treaties and inquires into the general process of treaty-making. Nevertheless, while, as ever, the government controls the allocation of time in the House of Commons under Standing Order S.O. No. 14(1)—if you only know one standing order, it really should be this one, because it’s comfortably the most significant—any debate on a treaty will be when the government allows time for it, if at all. In any event, the government can also simply declare under section 22 of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act that “exceptional” circumstances mean the treaty cannot be presented as otherwise required.

Enough of treaties: if the parliamentary scrutiny of international agreements is what really gets you going, the exceptionally learned Alexander Horne, barrister, legal adviser and a fine former colleague in both Houses, is your man. The point is that the treaty signed this week strengthening the UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership promises to guard against refoulement, strengthens the independent monitoring committee supervising the agreement, creates a new appeal body and thereby seeks to demonstrate that, contrary to the court’s judgement, Rwanda is a safe destination to which asylum seekers may be diverted.

What will the legislation we are promised actually say? There are, by all accounts, two options. The more modest is a short, technical bill—which is being dubbed, in revolting Westminster village language, “semi-skimmed”—which would disapply the Human Rights Act 1998 in respect of asylum claims. The second, “full fat” option, which has caused shortness of breath and excitedly pounding hearts in the Europhobic section of the Conservative Party, would remove the right of judicial review of the legislation and, through so-called “notwithstanding” clauses, essentially exempt asylum from the scope of the ECHR and any other international treaties to which the UK is a signatory. This latter course of action would be tantamount to, and might indeed end up in, the UK’s withdrawal from the ECHR, which some on the right have long favoured and for which Suella Braverman was thought to be paving the way with her speech at the Conservative Party conference in October.

Unusually, The Guardian reports, the attorney general, Victoria Prentis KC, has sought the advice of human rights specialists Matrix Chambers, where counsel include former director of public prosecutions Lord Macdonald of River Glaven KC, Twitter frequent flyer Jessica Simor KC and Murray Hunt, former legal adviser to Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights. It is the one-time home of Philippe Sands KC, Cherie Booth KC (Lady Blair) and the late Sir Paul Jenkins QC. This is unusual in that the Government Legal Department, the head of which, the Treasury solicitor, reports to the attorney-general, has 2,000 lawyers in-house.

Even if Sunak only opts for the “semi-skimmed” option, getting a bill through Parliament will not be easy, as I outlined in The Daily Express. The House of Commons should not be too much of a challenge: the government has a majority of 56 and the ability to impose a timetable on legislation, so it could perfectly easily put a Rwanda migration bill through all its stages in one day under an appropriate business of the House motion if it has the votes in the lobbies. That said, as it lost its first whipped vote of the 2019 Parliament on Monday evening, albeit only by four votes, chief whip Simon Hart may be a little gun-shy.

The trouble is widely anticipated to lie in the House of Lords. To some extent, we have been before with the stormy passage of the Illegal Migration Act 2023, which took three months and four rounds of “ping-pong” to get to the stage of Royal Assent just before Parliament adjourned for the summer. At the time, Braverman, as home secretary, was using inflammatory language to frame the actions of the Lords as somehow improper, frustrating “the will of the British people”, and I wrote in May that this was a bad business, dangerous, reckless and potentially an act of constitutional vandalism.

There are two factors at play now that differ from the battle in the summer. The first is that this is, almost certainly, the last session of this parliament. That means the Commons cannot fall back on the provisions of the Parliament Act 1911, as amended by the Parliament Act 1949, to get a bill on to the statute books without the consent of the Lords; a bill must be presented in the same form in two successive sessions, and the second readings must be a year apart, before the legislation can be “Parliament Acted”, as I realise I would say without hesitation in the familiar jargon of the practitioner. There is simply no time.

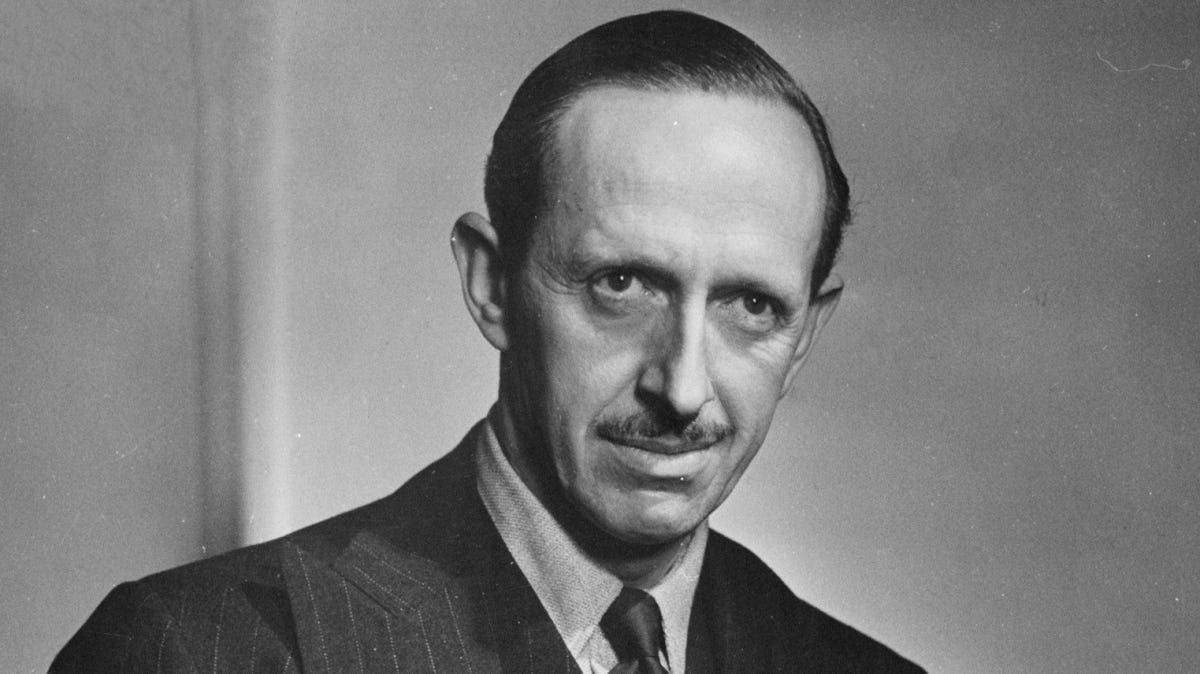

The other consideration is the Salisbury/Addison Convention (the “Addison” part is often omitted but Lord Addison, leader of the House of Lords from 1945 to 1951, 76 years old when he took on the position, is a remarkable figure, probably the most eminent physician ever elected to the House of Commons, and a rather greater figure, in truth, than Bobbety Salisbury, his opposite number throughout the Attlee government. Read about him). The convention, sometimes the “Salisbury Doctrine”, devised to cope with a House of Lords which in 1945 had 16 Labour peers from a total of 831 but a Labour government with a Commons majority of 145, essentially says that the House of Lords will not oppose at second or third reading a government bill which reflects manifesto commitment, since it is deemed to have the imprimatur of the electorate. Reasoned amendments may be offered at second reading provided they are not designed to wreck the bill. However, the idea of diverting asylum seekers or other potential migrants is contained nowhere in the Conservative Party’s 2019 manifesto, Get Brexit Done: Unleash Britain’s Potential. The most frequent related reference in the document is to the “Australian-style points-based system” (remember that?).

To an extent, therefore, the gloves are off in the upper house. The House of Lords has no provision for timetabling consideration of legislation, so the government must move forward by consensus, and, as cannot be stated often enough, it does not have a majority in the upper house: there are currently 785 peers, of whom 269 are Conservatives, 175 Labour and 81 Liberal Democrats, with the ever-present and always entertaining wild card of 183 crossbench peers, who are not aligned with any political party and do not take a collective view on policy, but who work together in administrative terms under an elected convenor, currently the Earl of Kinnoull, a Scottihs hereditary peer who spent 25 years working for insurance giant Hiscox and was elected to the House at a by-election in 2015. (As I have written before, hereditary peer by-elections are one of my favourite things.)

With a majority equating to a theoretical 393 votes (f every peer voted, the chances of which are zero), the Conservatives would be a long way short on their own even if they could guarantee the support of every Tory in the House. For context, a division on November 2020 in which the government was defeated on clause stand part of clause 42 the United Kingdom Internal Market Bill was the third-largest since the hereditary peers were largely excluded in 1999, and saw 433 Not Contents see off 165 contents, 598 peers in total participating. But the government business managers in the Lords, led by the leader of the House, amiable party veteran Lord True, and the chief whip, Baroness Williams of Trafford, a Cork-born Roman Catholic tempered in the fires of local government, cannot by any means assume every Conservative will vote as directed.

It has been assumed that the House of Lords will make things difficult for Rishi Sunak and drag its collective feet over scrutiny of a Rwanda bill, perhaps amending it heavily, submitting to the reversal of those amendments with minimal grace, and making the prime minister’s foot soldiers in both houses work for their eventual victory. The primacy of the elected House, the government is entitled to have its business, unaccountable peers etc. We can all draft the lines now. And, indeed, after weeks of trench warfare, with grave threats issued, harsh words spoken and grand promises made, that is probably what will happen.

The Lords may be able to delay long enough that the Rwanda policy makes no significant progress before the election, especially if that election were to come in May rather than, as I and many other suspect, October. Sunak may privately be grateful for that: there is, as I have argued many times, no evidence to suggest that the Rwanda plan will make serious inroads into the number of asylum seekers and potential illegal migrants, and, while the numbers are falling already, 37,556 people arrived in small boats in the year ending September 2023 (16 per cent fewer than the previous 12-month period). But these are not, anyway, where the big numbers are in terms of overall immigration: net legal migration in the year ending June 2023 was 672,000, and if the government wants to make a serious change in that figure, it will be through, as I argued in The i, detailed, concrete measures like those announced in the House of Commons on Monday.

It may suit the prime minister, therefore, to have the distraction of a constitutional confrontation with the House of Lords to veil the fact that the Rwanda policy is, as it always was, a signal of intent, a performative contrivance, not a serious instrument of working bureaucracy. If timing is on his side, Rishi Sunak can go to the country lamenting what might have been, like an unmasked Scooby-Doo villain who would have stopped the scourge of the small boats if it hadn’t have been for those meddling peers.

Politics, however, as we saw when Rishi Sunak brought David Cameron back to cabinet as foreign secretary, still has the capacity to surprise. Let me suggest one possible scenario that, while unlikely, cannot be ruled out.

We know that the Rwanda policy has already been declared unlawful in its practical application. The five Supreme Court justices who ruled on the matter (Lord Reed of Allermuir KC, president, Lord Hodge KC, deputy president, Lord Lloyd-Jones KC, Lord Briggs of Westbourne KC and Lord Sales KC) were unanimous in agreeing with the Court of Appeal that there had been no proper, thorough assessment of how safe a third country Rwanda was, overturning the December 2022 decision of the High Court of Justice (King’s Bench Division). That leaves quite a hill for the new treaty to climb in providing reassurance, unless the government relies on a bill stating that Rwanda is safe; this would not affect conditions in central Africa one jot or tittle, of course, but would make a declaration which is perfectly within the power of Parliament, whether it reflects reality or not.

We also know that there is insufficient evidence that the Rwanda policy is good value for money. Sir Matthew Rycroft, the permanent secretary at the Home Office, is, ex officio, principal accounting officer for the department and there bears responsibility for “ensur[ing] that the Department’s use of its resources is appropriate and consistent with the requirements set out in Managing Public Money”. In April 2022, he wrote to the then home secretary, Priti Patel, stating explicitly that, while there were “potentially significant savings to be realised from deterring people entering the UK illegally”, he had to consider the “high cost” of the policy and the evidential base for it was poor. He stated bluntly:

Evidence of a deterrent effect is highly uncertain and cannot be quantified with sufficient certainty to provide me with the necessary level of assurance over value for money.

Note that he was being as accommodating as possible: he freely conceded that the Rwanda policy might well “have the appropriate deterrent effect; just that it there is not sufficient evidence for me to conclude that it will”. In view of his inability to cite an evidential basis, he required the home secretary to issue him a ministerial direction: this is a document which, in essence, says that a civil servant was, to steal a phrase, only following orders. Rycroft knew he was unable to fulfil his duties as principal accounting officer and therefore the minister, in this case the home secretary, took the responsibility from him and made a decision on a political basis, as she, and not the permanent secretary, is directly responsible to the House of Commons for the work of the Home Office.

(Patel’s ministerial direction is worth reading: typically upbeat but with a hint of sorrowful menace, it reads like a New Year resolution that everything will be better, because it just has to be. My favourite phrase is her rueful dismissal as “imprudent” a course of action “to allow the absence of quantifiable and dynamic modelling… to delay delivery of a policy that we believe will reduce illegal migration”. That’s right: imprudent to allow a lack of evidence to stop you doing something you believe will work. The word “imprudent” does a lot of work there.)

In addition, we know that the electorate is yet to be convinced by the Rwanda policy. A YouGov survey conducted when the plan was announced found 35 per cent of respondents supported the policy, but 42 per cent opposed it. A poll carried out a year later by the dripping-wet centrist think tank More In Common showed support had risen to 46 per cent, with only 27 per cent opposing it; but that came with an important caveat that 51 per cent didn’t think the policy would deter those trying to cross the Channel in small boats (of whom three per cent thought it would increase the numbers!), and only 34 per cent of respondents believing that it would, in fact, work as planned.

Last month, a Savanta poll suggested a large minority, 47 per cent supported the policy, while only 26 per cent were against it. But when we come back to effectiveness, the same problem reappears: only a quarter of respondents think the policy will actually reduce the numbers of those attempting to cross the Channel, a quirky 13 per cent think it will increase the numbers (employees of the Rwandan tourist board?) but—and here’s the kicker—51 per cent think it will make no difference. That is, 18 months since the agreement with Rwanda was first concluded, after all the headlines and the legal back-and-forth, the high controversy and the departure of two prime ministers and two home secretaries, half of those asked think the policy will be ineffective in its principal goal, deterring would-be migrants from entrusting their lives to the operators of the wretched small boats to get across the English Channel.

Now, none of these arguments, none of these figures, is a slam-dunk. Whether you agree with the Rwanda policy is a matter of political judgement, priorities and ideology. What I am arguing, however, is that there are grounds for those peers who do not want the bill to pass or the policy to go ahead to think that perhaps it is worth a fight.

If we look years into the future, it is overwhelmingly likely that the duly elected government will get its way, whatever “its way” turns out to be. In this specific case, however, we have a government whose supporters are divided over this measure and a clock which is ticking ever more loudly. On the assumption that an incoming Labour government would not pursue it, and Sir Keir Starmer has called it the “wrong policy” and pledged to reverse it even if the legal hurdles were cleared, the Lords might have a chance of preventing this measure from coming into effect, simply by refusing to follow convention and precedent and back down after a reasonable level of dissent.

Let me take you back for a moment—this will be relevant, a little bit, I promise—to 16 August 1870. Near the village of Mars-la-Tour in the Moselle, in north-eastern France, III Corps of the Prussian Army, under the command of General Constantin von Alversleven, has just clanked into the French Army of the Rhine. It has been commanded for four days by Marshal François Achille Bazaine, a remarkable man from Versailles who rose from the lowest rank of the French Army to the highest in 32 years. French dragoons had first come under artillery fire, rather to their surprise, at 8.30 am, and once battle was joined, the French soldiers put up stiff resistance to the invading Prussians. By around 2.00 pm, four French corps were deployed, and Alversleven, needing to make a decisive move, sent his chief of staff to instruct Major General Adalbert von Bredow, commander of the 12th Cavalry Brigade, to attack the French artillery and relieve pressure on his forces.

Bredow’s brigade consisted of three mounted regiments: 7th (Magdeburg) Cuirassiers, 16th (Altmark) Uhlans and 13th (Schleswig-Holstein) Dragoons. The last had been detached earlier in the day, so he now mustered around 800 horsemen, and saw the odds against him. He was outnumbered four to one, but understood what his chief needed. An aide, surveying the prospect, asked with incredulity how many men would die to try to turn the tide of the battle. “Koste es, was es woll,” said Bredow. It will cost what it will.

Using a depression in the ground and the by-now-ample gun smoke, Bredow took his force to within 1,100 yards of the French before he was seen, then charged.The blow shattered the French lines, while an attempted counter-attack by French cavalry was derailed when French infantrymen started shooting indiscriminately at mounted soldiers of any nationality. By 3.00 pm, Bredow rallied his cavalrymen and withdrew, his task accomplished, but he had lost 380 of his 800 soldiers. The episode became known as Bredow’s Death Ride, one of the last major cavalry charges in European warfare: effective and necessary, but achieved at a fearsome cost.

Maybe the House of Lords would consider a death ride against the Rwanda bill. It could be effective: if Parliament is due to be dissolved in September, the legislation could with determination be held up till then, not least if a hard core was willing to threaten other parts of the government’s legislative programme. The cost would, one thinks instinctively, be high: the government would regard it as outrageous obstruction by the unelected house and would want to curb the power of the House of Lords further. It would be the equivalent, surely, of Samson pulling down the Philistine temple on himself.

Perhaps, yes. But the Conservative government has been promising or threatening reform of the House of Lords since 2010, while the Labour Party has pledged to abolish the chamber in the next parliament if it wins the election, replacing it with an elected “Assembly of the Nations and Regions” under plans drawn up by former prime minister Gordon Brown. (There are reports that this bold commitment is now under review.) Sir Keir Starmer is believed to be willing to create new peers within the existing arrangements if it is necessary to get business through. On the face of it, then, reform is coming anyway. What do peers have to lose?

Back to reality: I don’t think peers who oppose the Rwanda policy will take the “Bredow option”. All I would say is that we live in unpredictable times: many believe that the House of Lords in its current configuration is now an unwanted guest in the last-chance saloon, and it seems likely that within 12 months we will have a new government with clear and carefully drawn-up plans for a new upper house. (For clarity, I don’t like the Labour Party’s plans and think there are a lot of misconceptions about House of Lords reform.) Peers might, therefore, be guided not by fear of what might happen next, but instead by their straightforward estimation of the impact on the legislation in front of them. Simplicity, sometimes, is a wonderful palate cleanser.