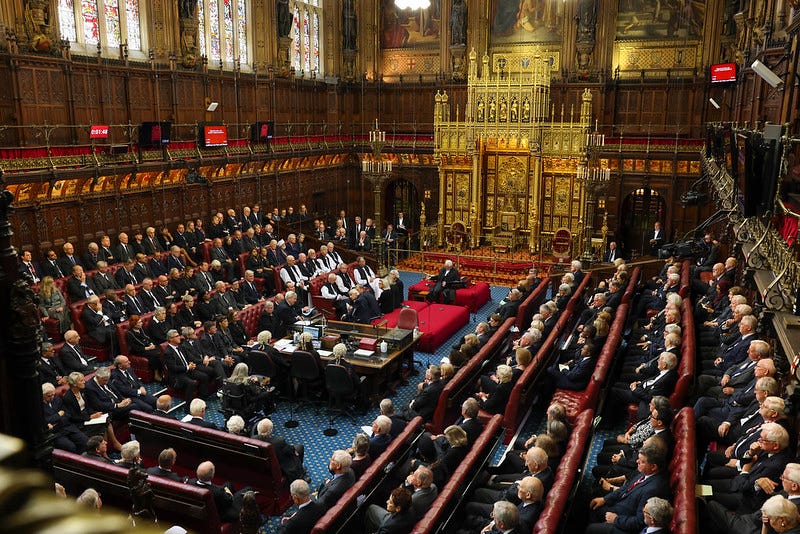

Attend His Majesty in the house of peers!

House of Lords reform is back on the agenda—so here are three popular myths about the upper chamber

I start, as I so often seem to, with a disclaimer, or perhaps a caveat. As a keen student of the British constitution, and an historian, I love the House of Lords. I worked close by it and with it for a decade, and I even briefly worked for it. I like its long pedigree, stretching back through the English Magnum Concilium to the Anglo-Saxon witan, which existed well before AD 600. This is heritage, this is a link, largely unbroken, with our earliest past as a recognisable polity, and reminds us that our institutions of state are in many cases quite dizzyingly old. And, like it or not, it is a mark of the earliest signs of the constraints of royal government: not of democracy, certainly, but of some sense that the community must be persuaded before the writ of kings can be enforced.

I am not, however, starry-eyed about the House of Lords as it is currently constituted. It is not perfect—but then what part of our governance is?—and there are elements of its composition, powers and procedure which could certainly be improved. Along with several other colleagues, I lost many hours of my professional life to the last major attempt at reforming the House of Lords, the draft House of Lords Reform Bill 2011, which a joint committee of Parliament scrutinised in great detail. It was, if I may say so, a typically Liberal Democrat measure, one of the terms of the 2010 coalition agreement, wonkish, slightly obsessive, other-worldly and answering a question no-one had really asked with any seriousness.

Now, the leader of the opposition, Sir Keir Starmer, has started up the auld sang again. Former prime minister Gordon Brown, chairing Labour’s Commission on the UK’s Future, has produced a report which, among other recommendations, proposes to “abolish” the House of Lords and replace it with an “Assembly of the Nations and Regions” (a weirdly Stalinist-sounding body, or something from the darkest imagination of the Council of Europe), to safeguard the constitution and help bind the United Kingdom more tightly together. I won’t tackle the recommendations here, though I might return to it if there is sufficient public clamour, and I don’t want to be too rude, as my old chum Professor Jim Gallagher, a comrade in arms from Scottish Affairs Committee days, was one of the commission’s advisers.

Quite the contrary, I want to take on some of the arguments of those who have leapt forward to oppose the commission’s recommendations (however dimly I may view this proposed “assembly”). I offer, therefore, three common myths about the House of Lords often, earnestly and passionately advanced in defence of the status quo or even, sometimes, the status quo ante 1999.

Hereditary peers provided an independent element of scrutiny not beholden to party machines.

Well, possibly. It’s a nice idea, isn’t it? We may not approve of the royal and political patronage which brought these aristocrats to our legislature, but at least they do not owe their places to favours from the current régime, and, as they inherit their seats for life, they are, in a sense, unimpeachably independent. After all, they have nothing to lose, do they? And they embody an old-fashioned and perhaps unfashionable sense of noblesse oblige, which is at least intended to benefit the public good.

The problem with this idea, charming as it is, is that there is little hard evidence for it. We think of the unreformed Lords as having an inbuilt Conservative majority, and, indeed, for a long time it did: in 1900, there were 354 Conservative peers in a house of 574, and by the time of the Second World War it was 519 out of 761. The balance began to change significantly after the passage of the Life Peerages Act 1958, which introduced the first major non-hereditary component into the house. By the twilight of the pre-reform house, in 1998, the number of peers had reached 1,272, but the Conservatives were now only the largest minority, with 496 peers against 158 Labour and 68 Liberal Democrat. But a substantial number of these, more than 660, were hereditary peers, with this idealised independence of spirit.

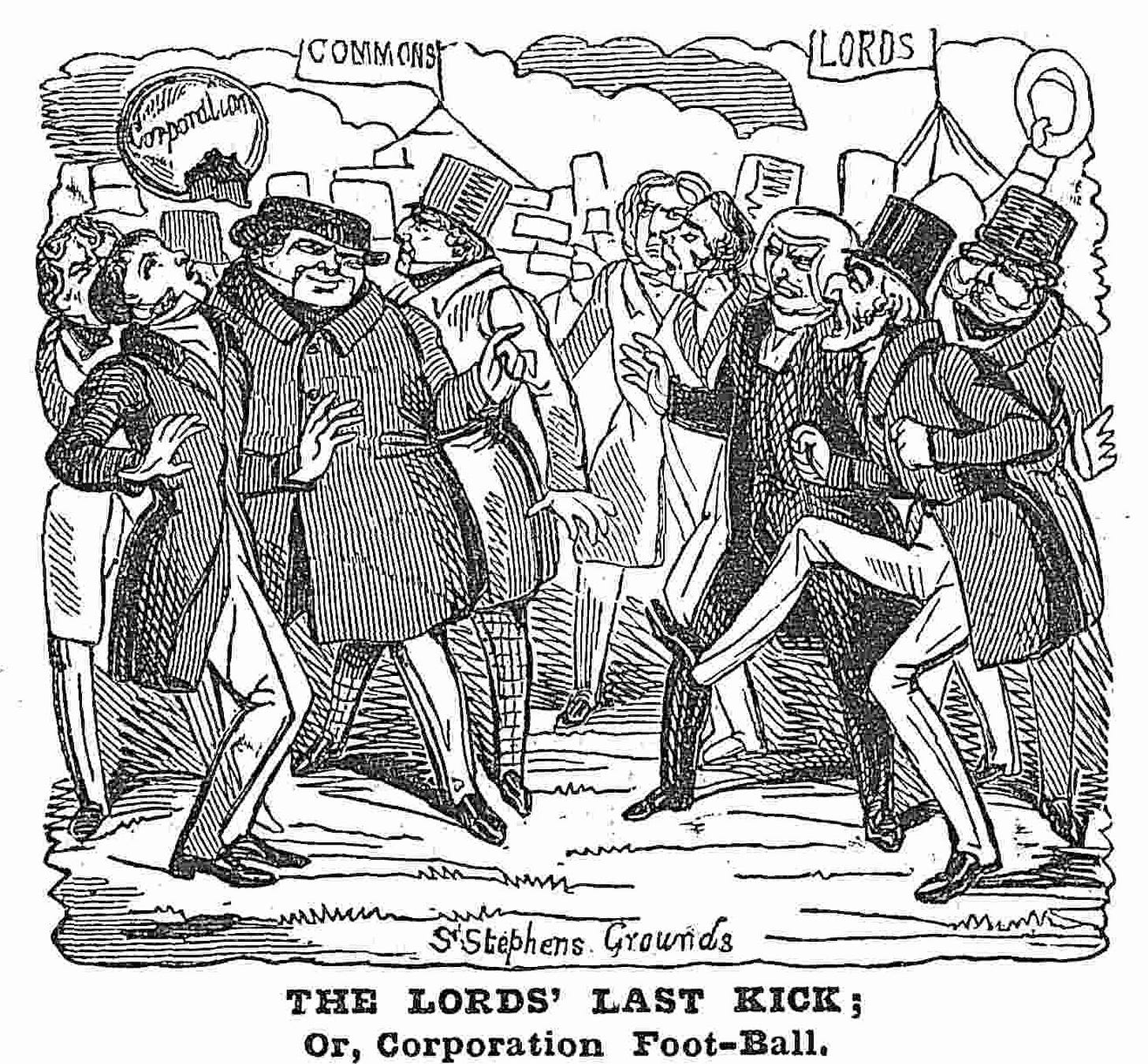

The “old” House of Lords was not, however, significantly more rebellious than the current chamber, and there is evidence that it voted more heavily Conservative than anything else, as one would expect from its membership. In the session 1988-89, for example, only 40 Conservative peers broke the whip more than once. And a look at government defeats in the house by session is instructive. In the Thatcher/Major years, it only once went above 20 defeats in a session, while the Blair government was defeated 39 times in 1997-98, 31 times in 1998-99, and 36 times in the last pre-reform session of 1999-2000. The record from the 1970s tells the same story. The Labour government was defeated 126 times in 1975-76, 25 times in 1976-77 and 78 times in 1977-78.

The truth, then, is that the old House of Lords was not particularly rebellious when a Conservative government was in office, even when the party had lost its outright majority, while it did rebel much more often against Labour governments. That, I’m afraid, is not independence of mind. That is simple party management.

The House of Lords is a revising chamber and acts to scrutinise legislation.

This is an interesting argument. We know, of course, that the Lords is a subordinate body to the Commons. Under the Parliament Act 1949, it can only delay legislation by a year (the first Parliament Act 1911 allowed two years’ delay); the Commons maintains financial privilege, by which it may overrule the Lords on any matter of public spending or taxation; and, according to the Salisbury Convention (or Salisbury-Addison Convention, to give Viscount Addison his proper recognition), the House of Lords will not vote against a government bill at second or third reading which stems from a commitment in an election manifesto.

But wait! There are other conventions and realities of day-to-day politics which ameliorate this supremacy of the elected house. The Parliament Acts are rarely invoked (seven times since 1911, one of which was to pass the 1949 act itself), because the parliamentary management of the process is incredibly time-consuming. Passing a bill using this nuclear option could easily mean that little other business is transacted, so a government which reaches for the Parliament Acts might find its victory distinctly Pyrrhic. And the real purpose of the upper chamber is, anyway, not so much to oppose outright but to scrutinise in detail, something for which the Commons has neither time nor capacity. In essence, our Parliament acts as an informal Platonic ideal, with the lower house providing political direction and impetus while the upper house does the difficult and unglamorous but essential work of making sure legislation works and is in good order. It can, and does, table amendments, by the hundred for controversial bills, and there is a kicker for the government’s business managers:

All suggested amendments have to be considered, if a member wishes, and members can discuss an issue for as long as they want. The government cannot restrict the subjects under discussion or impose a time limit.

This gives the Lords enormous “soft power” to influence legislation as it makes its way through the process towards Royal Assent.

It must be added to this, however, that many Lords amendments are rejected or overturned when they come back to the House of Commons. This part of a bill’s consideration receives little publicity—admit is, how many of you would swiftly turn on BBC Parliament to watch “Consideration of Lords Amendments”? And it can happen very quickly. Amendments are sometimes tabled to test the government’s strength of will, to force a compromise or to make a point, and they can be dismissed by the Commons in a matter of minutes if the government is so minded. There is also a haze of impenetrable language about some of it. How many without a freakish interest in procedure would know what it meant if the Commons agreed to a Lords amendment with an amendment, or disagreed with a Lords amendment and tabled an amendment in lieu?

Think I’m being patronising on that last point? Well, watch Simon Burton, then (I think) clerk assistant (deputy clerk) of the House of Lords inform their Lordships of the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill has fared in the Commons as the lower house considers Lords amendments. If any of that was too fast or incomprehensible, here is what he said:

MESSAGE FROM THE COMMONS that they agree to certain amendments made by the Lords in lieu of amendments made by the Lords to the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill to which they disagreed; they agree to the amendment made by the Lords to their amendment made in lieu of an amendment made by the Lords to which they disagreed; and they agree to the amendments made by the Lords to their amendments made in lieu of the amendment made by the Lords to which they disagreed with amendments, to which they desire the agreement of your Lordships.

I take it that’s clear? (Have a little sympathy: once upon a time it was my job to prepare the wording of these messages from the Commons, and working out exactly what had happened to a complex bill was not always easy. As one of my bosses said of that role, “High risk, high reward.” The first half was true.)

In the end, there is a basic understanding which politicians in every part of the institution ignores at his or her peril: the House of Commons has procedural levers to enforce its will, and although the fight might well be bloody, the result can only go one way. Moreover, if the battle spills beyond Parliament into—I shudder at this phrase—the court of public opinion, creating a narrative which favours an unelected chamber of 800 peers over the elected representatives of the people, however imperfect, is always going to be a challenge. I shy away from Quintin Hailsham’s famous phrase, “elective dictatorship”, but the House of Commons will not be frustrated for too long on genuinely important measures. This is not to say the Lords is a cipher: it does valuable work. But we must not invest its scrutiny with too much sanctity when we look at our constitutional arrangements.

The House of Lords is a “house of experts”.

Isn’t it pretty to think so? One undeniable fact to begin: a largely elected house, however it was composed, would almost certainly not have eminent scientists, philosophers, engineers, physicians, economists, judges, academics, business leaders and artists in it in the way the current House of Lords does. Only appointment allows us to include these people in our legislature (I think for the better), and the fact that peers are only paid for days when they participate in proceedings mean that these eminent men and women need not attend on a regular basis as party hacks but can contribute only when they feel their expertise can materially enhance the work of the house. It is a major strength of the current arrangements.

And we all, I’m sure, have our favourite “expert” peers. (Just me?) I always enjoy surgeon and geneticist Robert Winston’s contributions; Edward Faulks is a welcome source of legal expertise and insight; we would be much the poorer without the wisdom of Peter Hennessy, the foremost recorder of modern British government; and I look forward to hearing from historian and biographer Andrew Roberts. In my brief life as a committee clerk in the House of Lords, my own committee included a former cabinet secretary, a leading economic historian and an ex-company secretary for a FTSE 100 company, none of whom would have been in an elected assembly.

But we mustn’t allow ourselves to be carried away. The Lords is not some sort of academy of arts and sciences, some kind of symposium of professors and consultants and judges and writers and engineers. Those exist in the house, certainly, but they are not the most active peers. To begin with, of the 800-odd peers, more than 170 are former Members of Parliament. I have no quarrel with the idea of retaining political experience, but these are no more expert than they were when they were elected to the House of Commons. Further peers are drawn from the ranks of party officials and workers, or political appointees to government office.

The notion of a “house of experts” is also very partial. Some sectors are very well represented, such as the law, finance, business and science, but there are relatively few peers who have recent experience of what we might call “front line” public services, industry, transport and manual trades. It is selective expertise: impressive by comparison with other legislatures, but not the unique blessing which defenders of the status quo make it out to be.

I am by no means condemning the current House of Lords. As a second, weaker chamber of parliament, given the system which obtains at Westminster, it performs moderately well in its assigned role. Even when there was a mild stramash in October about a list of new peers chosen by Boris Johnson, I thought the outrage was somewhat synthetic: few if any of those nominated were utterly unsuitable for elevation, and I doubt any would make it into the top 20 stupidest or most useless peers.

I merely ask that those who insist on tackling the issue of reform of the House of Lords, if they have really decided that their journey is necessary, do not proceed on the basis of inaccurate perceptions. It is always a danger that reformers will see their intended outcome as an institution of holy perfection, but those who oppose reform must also be realistic about what exists now and what has gone before. Our political institutions, however little we may sometimes value them, are extraordinarily precious, and their antiquity proves a degree of durability and—damn your eyes, John Reid—fitness for purpose. When we change, let us be clear both what we are changing as well as what we are creating anew. Honesty really is the best policy.