Access and influence in foreign policy: if we make sacrifices to get close, there must be a pay-off

Britain often prides itself on 'special relationships' but these come at a cost; and it's only worth it if there is a tangible benefit

“Free to those who can afford it, very expensive to those who can’t.”

Those are the words Withnail uses to describe his Uncle Monty’s holiday cottage, Crow Crag, in the wilds of Cumbria as he dangles the key in front of Marwood in Bruce Robinson’s 1987 blacker-than-black comedy. It’s a phrase which sums up access, I think, but also influence: Withnail flatters and panders to his eccentric uncle, but gets the result he wants: the cottage in the country.

This is an essay about foreign policy. It’s about diplomacy and international relations, but it’s also about politics, and about human interactions. It deals with a peculiarly British concern which is an aspect of punching above your weight on the world stage: our history and perhaps our national character means that we will not and cannot—perhaps should not—measure our global importance by bare metrics like gross domestic product or trade balance. Instead, we believe that we can use skill and legacy and luck to have a greater heft than we might on those bare metrics deserve. Up to a point, I think that’s true, though we need always to be on guard against convenient illusions.

It is not an essay about the so-called “Special Relationship” between the United Kingdom and the United States (though I will write about that at some point), but I will use that as a starting point and a reference point to answer the fundamental question, which is this: when dealing with a foreign power, what is the difference between “access” and “influence”, where do we have it and how can we turn one into another?

The road to war in Iraq

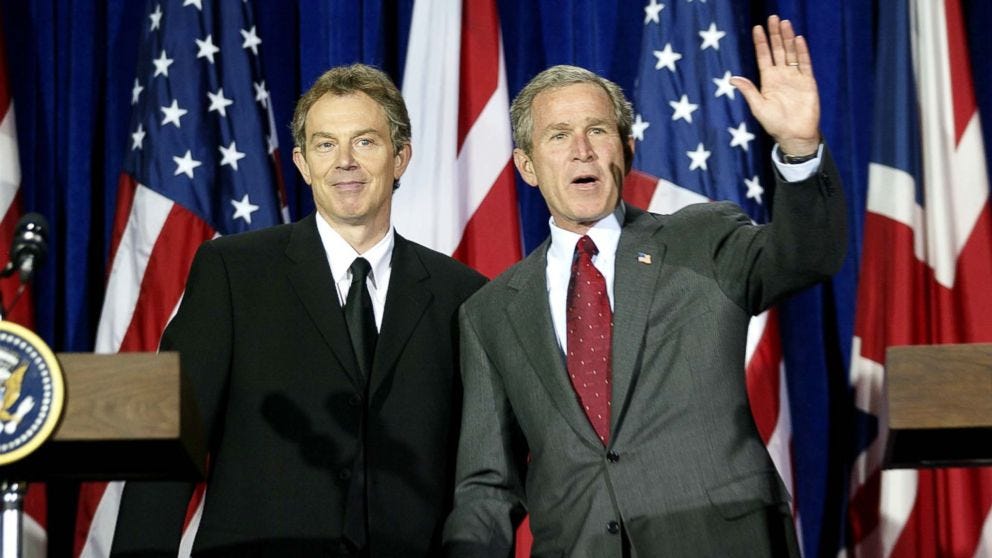

Let me start, then, with the United States, with President George Bush and Sir Tony Blair, and our steadfast support for the US in the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Regular readers will know that I will defend the invasion up to a point, think it achieved some positive results which are not wholly negated by the disaster which flowed from the coalition’s poor-to-non-existent post-conflict planning and believe there is a case to be made that it was not, as its opponents repeat again and again, an “illegal war”. I touched on some of these issues last year.

You can reach back almost as far back in time as you like to begin the story of what the Americans called with characteristic drama Operation Iraqi Freedom. (The Ministry of Defence here does things differently: for British personnel it was Operation TELIC.) It is certainly the case that the removal of Saddam Hussein was part of Bush’s foreign policy vision from the beginning of his presidency in 2001: part of the Republican platform had been full implementation of the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, and that legislation was absolutely explicit.

It should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq.

The act itself looked as far back as the beginning of the Iran-Iraq War in September 1980 to build its case against Saddam, although it is true, and was inconvenient that in the early 1980s the US favoured Iraq over Iran, and Donald Rumsfeld, from 1983 to 1984 President Reagan’s special envoy to the Middle East but then secretary of defense under President Bush from 2001 to 2006, had visited Iraq and been filmed shaking hands with Saddam.

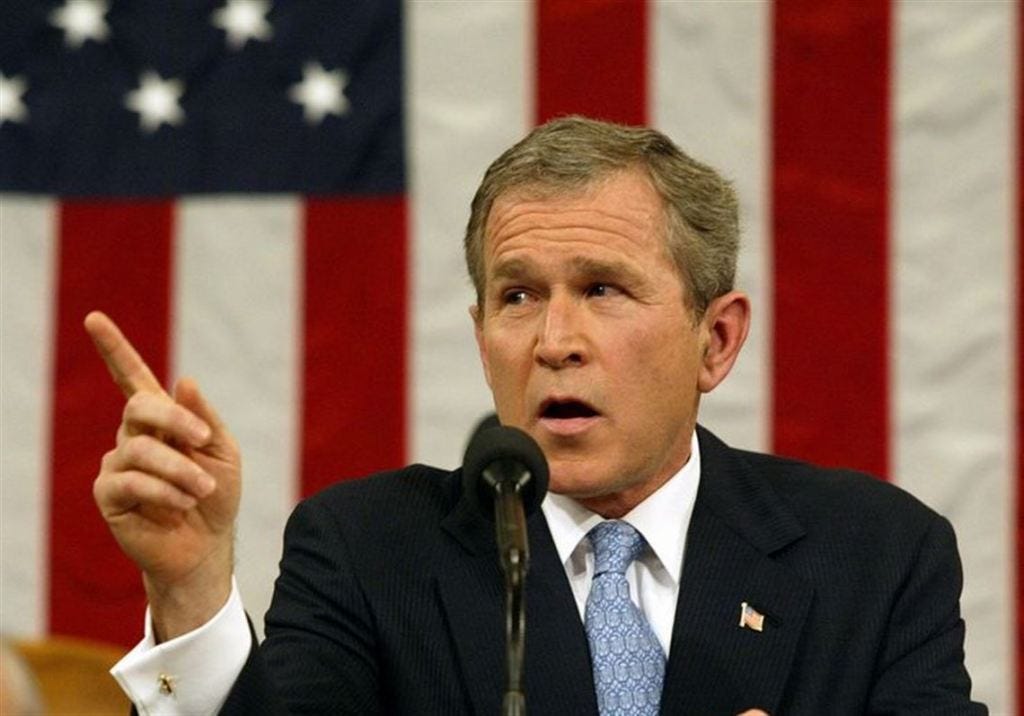

If it was in the new president’s mind at the beginning of 2001, the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington on 11 September that year changed the game for everyone. Bush’s State of the Union address to Congress in January 2002 said that “Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror” and was “a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world”. Together with Iran and North Korea, Iraq “constitute[s] an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world”, and he warned any hostile power that “America will do what is necessary to ensure our nation’s security”.

By that stage, then, military action against Iraq, probably decisive military action, was in the post. On 9/11 itself, it was later revealed, Rumsfeld had asked his staff at the Pentagon whether justification from that day’s events could be found to move against Saddam. In November, Rumsfeld sketched out in a memorandum some potential scenarios, and in hindsight it was only a matter of time before auspicious circumstances arose. United States Central Command already had a plan for taking on Iraq, OPLAN 1003. and Rumsfeld asked them to update it.

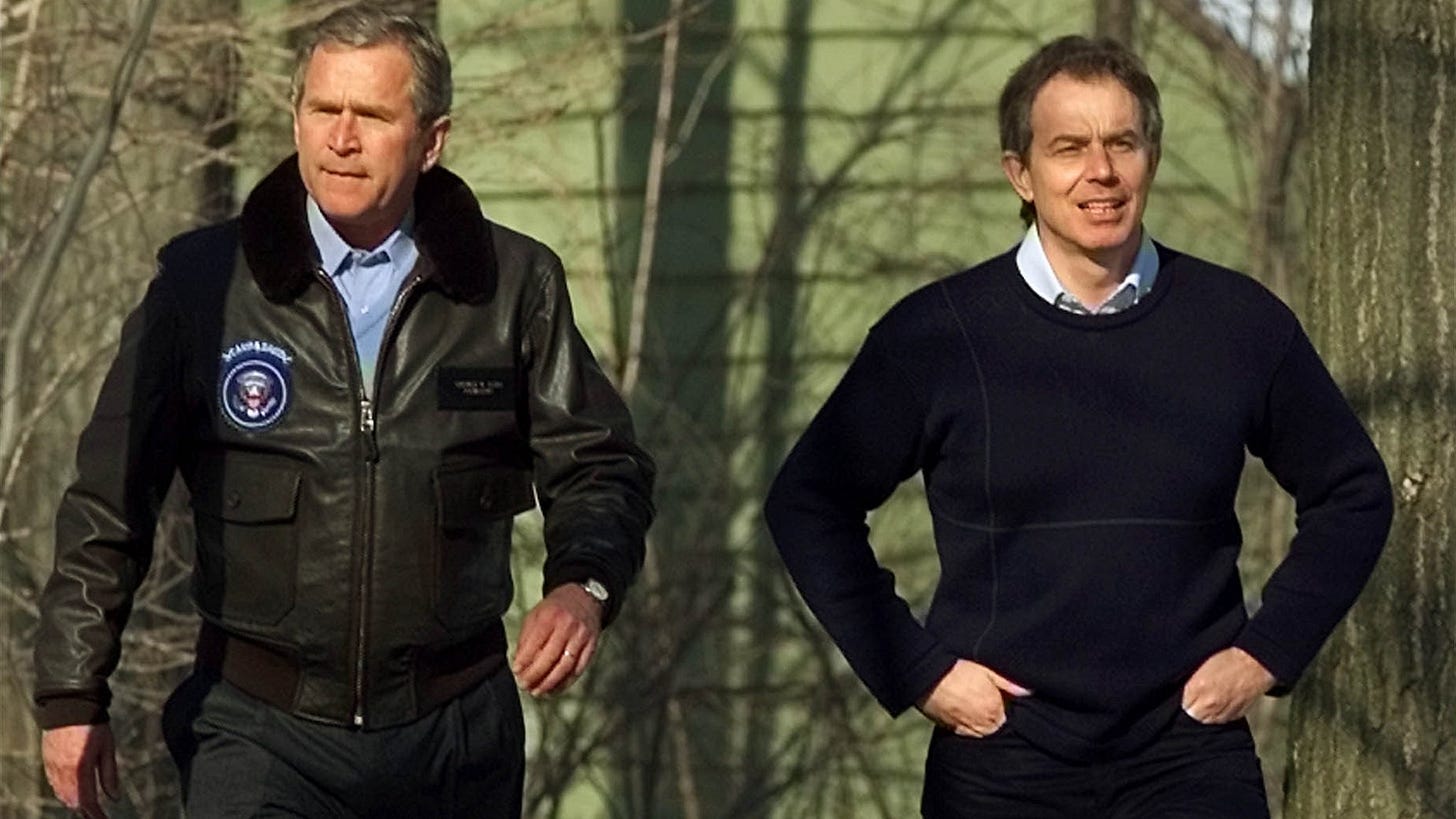

In April 2002, Tony Blair, who had led Labour to a second overwhelming general election victory the previous summer, travelled to Bush’s Prairie Chapel Ranch at Crawford in Texas. He was accompanied by his chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, the Downing Street director of communications and strategy, Alastair Campbell, and David Manning, head of the Cabinet Office Defence and Overseas Secretariat and the prime minister’s foreign policy adviser. Neither the foreign secretary, Jack Straw, nor the UK ambassador to the United States, Sir Christopher Meyer, attended.

Before the meeting took place, the US secretary of state, Colin Powell, sent Bush a memorandum to brief him. In it, Powell assured the president that Blair’s support was unconditional.

On Iraq, Blair will be with us should military operations be necessary. He is convinced on two points: the threat is real; and success against Saddam will yield more regional success.

Powell also informed the president that the prime minister was looking at how to make military action palatable in presentational terms.

Blair may suggest ideas on how to make a credible public case on Iraqi threats to international peace… [and] handle calls for a UNSC blessing that can increase support for us in the region and with UK and European audiences.

Finally, Powell acknowledged that Blair was taking a political risk and set out for President Bush his rationale for doing do.

Blair knows he may have to pay a political price for supporting us on Iraq, and wants to minimize it. Nonetheless, he will stick with us on the big issues. His voters will look for signs that Britain and America are truly equity partners in the special relationship.

This is significant, because in public Blair’s position remained that he favoured a diplomatic resolution to the situation with Iraq. At the beginning of the summit in Crawford, he said “We’re not proposing military action at this point in time”. That could strictly speaking have been true, but if Powell’s memo was a true reflection of the UK’s position, then Blair had already decided that he would support a military solution if diplomatic means failed. It was the belief of the State Department, therefore, that whether a compromise could be reached or not, whether a UN Security Council resolution authorising force could be obtained, the US could still rely on British support.

In July, Blair sent a private memorandum on Iraq to Bush. It began by saying “I will be with you, whatever”. He argued that, in terms of the removal of Saddam, “the US could do it alone, with UK support”. The memo then outlined the difficulties, and made the point that political and public opinion in Europe was far less gung-ho than in America. At this point, Blair was quite clearly still thinking through options short of military action. He told the Chilcot Inquiry in January 2010, “What I was saying... was ‘We are going to be with you in confronting and dealing with this threat’.”

What I think we can say with some certainty is this: Tony Blair was open to the option of reaching a solution to the impasse which stopped short of military action against Iraq, or of obtaining a specific UNSC resolution authorising the use of force. It may well have been his preferred option. But any reasonable reading of the evidence makes it clear that his fallback position was that the United Kingdom would support Bush, even if military action became the chosen course of action. Furthermore, he was sufficiently alive to the possibility of an invasion that he suggested possible timelines for it. To try to deny that is to twist the meaning of words into shapes which are both awkward and incredible.

I don’t want to dwell too heavily on the intricate details here but the point I want to underline is that Blair had taken a decision, certainly before April 2002, that the overriding priority was the UK’s support for America, which included supporting military action. This fits into a wider pattern of seeking maximum access to President Bush. Blair has arrived in Downing Street while Bill Clinton was only months into his second term as president. The two men had first met in January 1993, when Blair was shadow home secretary and had visited Washington with Gordon Brown, the shadow chancellor. Jonathan Powell, then political secretary at the British Embassy, had arranged for them to meet the newly elected president. There had been an immediate rapport; although Clinton was nearly seven years older than Blair (at that point 46 to Blair’s 39), they were both young by political standards, of the same generation, and committed to modernising, centrist politics.

After Blair’s election in May 1997, he and Clinton had formed an excellent working relationship. When Sir Christopher Meyer had been appointed ambassador to Washington a few months afterwards, Jonathan Powell had told him “We want you to get up the arse of the White House and stay there”. Blair saw the value in his personal rapport with Clinton, and the transcripts of telephone conversations between them, released in 2016, showed how warm and co-operative it had been. They had spoken on the day of Blair’s election victory, 1 May 1997, when Clinton had told him “I wish you well and look forward to working with you”. Blair had responded, “We have a chance to do something now. I look forward to meeting with you. We have a good and strong relationship.”

This had been borne out, as the two men had worked in the Northern Ireland peace process, culminating in the signing of the Belfast Agreement in April 1998. The following year the UK had provided valuable support in negotiating the Rambouillet Agreement which had created an autonomous Kosovo and made provision for a NATO peacekeeping force to be deployed. When the Yugoslav government had refused to sign up to the agreement, the UK had contributed to the US-led NATO bombing campaign between March and June. This had led to a Yugoslav withdrawal from Kosovo and the conclusion of the Kumanovo Agreement, and the UK had been the largest contributor to the KFOR peacekeeping force on the ground.

The nature of their politics had been a vital ingredient in the relationship between Blair and Clinton. During the presidential election of 1992, Bill Clinton had projected himself as a new kind of Democrat, rejecting the old-fashioned and ossified positions of the Left and the Right. Indeed, he had implicitly set aside ideology altogether in favour of practicality and flexibility: “we had better be willing to park all this aimless hot-air rhetoric at the door and deal with the people’s problems and the people’s agenda”. What Clinton saw was an opportunity to step away from an old political paradigm and, in the words of The New York Times, he “positioned himself as a centrist, and the idea of third-way politics is at the heart of his vision of himself and of a resurgent Democratic Party”. This was vital. By 1992, the Democrats had only won one presidential election in the preceding six.

When Blair became leader of the Labour Party in 1994, the potential of Clinton’s philosophy was obvious and pressing. The party had not won an election for 20 years, and had not won a working majority for nearly 30. Blair was already interested in the work of the sociologist Professor Anthony Giddens, and a few months after Blair became leader, Giddens published Beyond Left and Right, which posited a new framework for radical politics by drawing on what he called “philosophical conservatism” but applying it to the values of the Left. In 1998, Blair wrote of his political approach:

It is a third way because it moves decisively beyond an Old Left preoccupied by state control, high taxation and producer interests; and a New Right treating public investment, and often the very notions of “society” and collective endeavour, as evils to be undone.

All of this meant that the eventual victory of George W. Bush of the Republican Party, after some delays counting the votes in Florida, should have been a challenge for Blair. His close ideologically ally had been replaced by a right-wing politician who described himself as a “compassionate conservative” but was still in favour of lower taxation and was endorsed by Ross Perot, Steve Forbes and the National Right to Life Committee. Writing in 2008, Blair’s wife, Cherie Booth, revealed that “our hearts sank when the result [of the presidential election] was finally ratified”. The prime minister’s chief of staff, sent to Washington in the weeks before Bush’s inauguration to make contact with the new administration, warned “It will not… be as cosy as with the Clinton administration. Unlike Clinton they will not do political favours for us.”

This made Blair, if anything, more determined to forge a good relationship with the new president. When the US Supreme Court confirmed Bush as the election winner in December 2000, Blair was the first Western leader to congratulate the president-elect in an eight-minute telephone conversation which, his private office noted, created “as good a rapport as one could hope for”. Blair asked if he could address the president by his forename, to which George readily assented (but for the time being called Blair “sir”).

In February 2001, Blair travelled to the president’s country retreat, Camp David in Maryland, for his first face-to-face encounter with Bush. It was a triumph. Martin Kettle in The Guardian related that “Mr Bush exceeded all British expectations in a performance full of charm, warmth and political support for the British prime minister”. The president told the media that the UK was “our strongest friend and closest ally” and that the prime minister was “a pretty charming guy”. In future, he went on, when he needed to contact London, he could be confident that “there’ll be a friend on the other end of the phone”.

The two men discussed Iraq at that early stage. Bush dismissed the United Nations sanctions against Saddam Hussein as “like Swiss cheese; that means they are not very effective”. He clearly felt, however, that he and Blair were on the same page.

I think the prime minister and I both recognize that it is going to be important for us to build a consensus in the region to make the sanctions more effective… a policy of strengthening our mission to make it clear to Saddam Hussein that he shall not terrorize his neighbors, and not develop weapons of mass destruction.

Blair echoed this sentiment. He reiterated that Saddam remained a serious threat to his neighbours, and that the UK and the US shared a determination to deal with him.

Don’t be under any doubt at all of our absolute determination to make sure that the threat of Saddam Hussein is contained and that he is not able to develop these weapons of mass destruction that he wishes to do. And as I constantly point out to people, I mean, this is a man with a record on these issues, both in respect to the murder of thousands of his own people, in respect to the war against Iran, in respect to the annexation of Kuwait.

This was the trajectory of the Bush/Blair relationship. Having seen the benefits of his closeness to Bill Clinton, Blair was determined not to let the Special Relationship waver or diminish under a new president. It seemed natural, therefore, to adhere as closely as possible to the United States on Iraq, as well as on other issues, and he articulated this powerfully in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. The Manichaean world view which Bush formed in the wake of that day seemed to come easily to the prime minister, and when he spoke to the media outside Downing Street that day, his message was clear.

This is not a battle between the United States of America and terrorism, but between the free and democratic world and terrorism. We therefore, here in Britain, stand shoulder to shoulder with our American friends in this hour of tragedy. And we, like them, will not rest until this evil is driven from our world.

It is hard to disentangle Blair’s motives (and I don’t mean that to be derogatory). He and George Bush were both motivated by a deep religious—Christian—faith. Bush was raised an Episcopalian, attended a Presbyterian church as a young man but moved to the United Methodist Church when he married his wife Laura in 1977. Having become acquainted with Southern Baptist preacher Billy Graham, he became a born-again evangelical Christian in 1986 after deciding to give up drinking and embrace God. Bush later revealed that he read the Bible every day during his presidency, although he was not a literalist, and was comfortable talking about the influence of God on his decision-making.

Blair had attended the Chorister School, an Anglican establishment in Durham, then Fettes College in Edinburgh, where chapel services were conducted by Church of England and Church of Scotland clergymen. As a undergraduate at St John’s College, Oxford, he had been strongly influenced by the Reverend Peter Thomson, a charismatic Australian Anglican minister who had helped him develop a left-wing religious outlook, but after his marriage to fellow barrister Cherie Booth in 1980 he began attending Catholic Mass with her, and his children were raised Catholics (Blair himself would convert in 2007). Alastair Campbell’s diaries disclosed that the prime minister read the Bible regularly, especially “when the really big decisions were on”. When Blair was interviewed for Vanity Fair by David Margolick in 2003, however, Campbell headed off questions about religion by saying “We don’t do God. I’m sorry. We don’t do God.”

The interview revealed much about the Bush/Blair dynamic, however. It was not that they were very similar people—“They’re not on the same planet, really”, said John Rentoul, his biographer—but their faith was, in Margolick’s word, “emboldening”. It gave them a reference point, witnessed by their mutual habit of turning to scripture in times of crisis, and it offered a clarity, a moral purpose which could translate into a strange kind of optimism, or at least a belief that the world could be made better.

This brings us back to the preparations for war against Iraq. If Bush was more sanguine about the prospect of military intervention, and could, as president of the United States, afford to be more cavalier about the support of other nations and international institutions like the UN, they shared a common position. This was that going to war with Iraq was firstly not the end of the world, and secondly on some level morally correct.

In those terms, therefore, by 2002/03, Blair had clearly developed and entrenched “access” to two successive American presidents, and must have believed, with some justification, that there was a “special relationship” between the US and the UK. Moreover, he believed that it was qualitatively different from the interaction America had with other countries, and that, at its best, it was underpinned by a core of moral virtue, a desire to do the right thing.

This mental construct was not a bad or damaging one. When Winston Churchill had imagined Britain’s place in the world in 1948, he had talked about “three great circles among the free nations and democracies”, which he took to be the Commonwealth and Empire, the wider English-speaking world, and a united Europe. He had identified Britain as “the only country which has a great part in every one of them” and whose role could be as the fixed point bringing them all together. Churchill’s grand vision was in some ways unrealistic, an attempt to find a new but continuing relevance in a world in which it had been substantially diminished. By the time Blair was prime minister, expectations of the UK’s global influence were more realistic, but there was still a sense, and an achievable one, that our history and our interests in various parts of the world gave us an ability to connect. Central to this was a close, “special” relationship with the US.

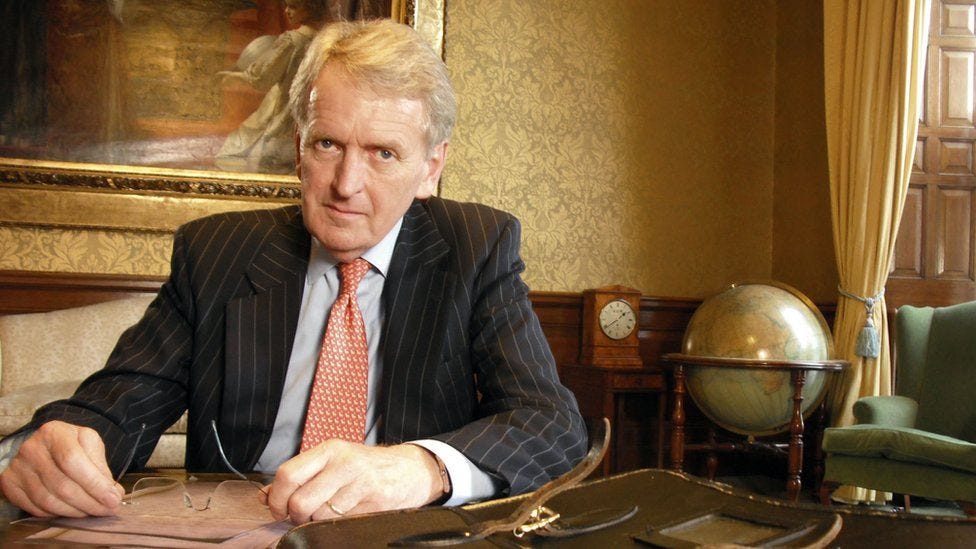

With regard to Iraq, the British government believed it could be a kind of counsel to the US, the wise voice close to the ear of the world’s only superpower. Christopher Meyer, from his vantage point in the Washington embassy, felt that “We may have been the junior partner in the enterprise, but the ace up our sleeve was that America did not want to go alone” in Iraq. There was, he went on in his 2005 memoir DC Confidential, an opening for Britain to use its special status and access which offered the chance that “Iraq after Saddam might have avoided the violence that may yet prove fatal to the entire enterprise”.

For Meyer, the failure was Blair’s. The prime minister was “seduced by the glamour of US power”, and should have demanded a “plain-speaking conversation” which could have changed American policy: the invasion should have been put off until the autumn of 2003, there should have been more planning for the post-conflict period and there might even have been the possibility of securing a UN Security Council resolution explicitly authorising military force.

Meyer addresses exactly the question of how a smaller nation like Britain could hold some sway over the US. His advice is absolutely clear: “establish your network of contacts, because if you cannot get access to people who know things, change things, you are stuffed”. That word, “access”. If you have that, Meyer’s argument runs, you are able to have those “plain-speaking conversations” and that is how, behind the scenes, you “change things”.

I liked Christopher Meyer, who died in July 2022. While the publication of his frank and witty memoirs upset many in government, I found them hugely enjoyable and very revealing about modern politics and diplomacy, and I admired his vivid turn of phrase and swashbuckling attitude, which was atypical for a senior ambassador. On the idea of the UK exercising influence over the US on Iraq, however, I think he was wrong. Bush and his senior national security team, especially Vice-President Dick Cheney, secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld, his Pentagon deputy Paul Wolfowitz and national security advisor Dr Condoleezza Rice, were determined from a very early stage to military action as the only way to achieve régime change, the removal of Saddam Hussein and the creation of a liberal democratic state in Iraq.

Cheney in particular had little regard for the United Nations, and felt that a resolution was unnecessary. In January 2003, only two months before the invasion, he gave a speech to the Conservative Political Action Conference in which he underlined the right of the United States to act unilaterally against Iraq. Warning that “the course of this nation does not depend upon the decisions of others”, he said:

Whatever action is required, whenever action is necessary, we will defend the freedom and the security of the American people… I have the honor of standing beside a great President who is determined to prevent the world’s terrorists and their sponsors from realizing their evil ambitions.

For Cheney, Saddam had been given every chance by the UN to disarm, to co-operate with weapons inspectors, to show the world that he was complying with international opinion. Yet “Saddam has absolutely no intention of complying with the world’s demands”. Given these tough words, spoken in public so soon before the invasion, it is hard to see where Britain might have exerted influence and made the Bush administration believe that it should seek yet another statement of intent from the UN.

I am also unpersuaded that the United States regarded British support and participation in military action as a sine qua non. Only a week before the eventual invasion, Donald Rumsfeld had been asked by a reporter if the US would go to war without Britain, given that support in the UK for military action seemed to be dwindling.

Their situation is distinctive to their country and they have a government that deals with the parliament in their distinctive way and what will ultimately be decided is unclear as to their role.

Although the participation of such a close ally would be “welcomed”, Rumsfeld continued, “to the extent they are not, there are work arounds and they would not be involved, at least in that phase of it”.

Rumsfeld’s remarks caused panic in Whitehall. It was true that he could be careless with words, and almost recklessly cultivated a reputation for unvarnished truth-telling, but he was not stupid and he was, moreover, the United States secretary of defense. Ministry of Defence officials quickly labelled the idea of unilateral action by the US as “unthinkable” and said plainly “if the Americans go in, we go in too”. But, to borrow from Mandy Rice-Davies, I tend to think of the MoD’s insistence, well, it would, wouldn’t it? It was essential to the conception and image of British power that our involvement would be a decisive factor in the course America chose. I am perfectly willing to believe that almost anyone in Washington would have preferred to have British support and UK forces as part of the military effort against Iraq.

I simply do not believe, however, that a British attempt to apply the brakes, certainly by the beginning of 2003, would have changed the course of US policy. The American deployment at the beginning of the invasion was over 465,000 personnel, not much less than two-thirds of the total coalition forces. The British contribution, while very substantial by our standards, was 50,000: more than any other nation, certainly, although the Kurdish Peshmerga security forces in northern Iraq were believed to number 70,000. Although the coalition was on paper outnumbered—the Iraqi armed forces had 538,000 active personnel and 650,000 reserves—these were of very varying quality, and the coalition nations had seen during the first Gulf War in 1991 that Iraqi resistance would be at best inconsistent.

Essentially, I think if Blair had suddenly told Bush that he could no longer commit British forces to an invasion and that the 50,000 sailors, soldiers and airmen would have to stand by while the US went in, Washington’s reaction would have been to regret the decision, but to press ahead anyway. We simply did not have the influence to prevent Bush from invading Iraq.

Finally, I do not accept that the UK missed an opportunity to ensure greater planning for the post-conflict period. Bluntly, it was not a matter our shying away from “plain-speaking conversations”, in Meyer’s phrase. These conversations took place. The planning proved inadequate because the Americans did not listen and we were unable to transform our access into influence.

The senior British commander with responsibility for post-conflict planning was Major General Tim Cross. Originally commissioned into the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, he worked in guided weapons and then logistics, he served as commander supply for 1st (UK) Armoured Division during Operation Granby, the 1991 liberation of Kuwait. After several roles in the Balkans, he was appointed director general defence supply chain at the MoD in 2000 and became involved in planning for Iraq when he set up the Joint Force Logistic Component for the invasion. Early in 2003, he was named senior British representative to the US Department of Defense’s Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA) under director Jay Garner, a retired US Army general and another missile expert. The role of ORHA was to administer Iraq after the successful conclusion of a military phase, administer aid and rebuilt infrastructure.

Cross was well aware that the planning was inadequate. A few months after he retired from the army in 2007, he told The Daily Mirror “we were all very concerned about the lack of detail that had gone into the post-war plan and there is no doubt that Rumsfeld was at the heart of that process”. Cross briefed Rumsfeld immediately before combat began and explained that there were inadequate resources for what the coalition needed to do, and there needed to be more involvement from the international community.

He didn’t want to hear that message. The US had already convinced themselves that, following the invasion, Iraq would emerge reasonably quickly as a stable democracy. Myself and others were suggesting that things simply would not be as easy as that—they didn’t want to hear that.

He conveyed the same message to his own government. He told the Chilcot Inquiry in 2009 that preparations were “woefully thin”, and that he had briefed the prime minister a day before the military campaign began.

I was as honest about the positions as I could be, essentially briefing that I did not believe postwar planning was anywhere near ready. I told him that there was no clarity on what was going to be needed after the military phase of the operation, nor who would provide it.

So it is clear that “conversations” did happen. It was not a matter of the British staying silent and missing opportunities to influence our partners. We spoke up, but we were not listened to.

It is not fair to say no thought was given to the post-conflict period. In August 2002, it was reported in Washington that a largely civilian “Iraq planning unit” had been established in the Department of Defense, and that officials were co-operating with the Iraqi opposition, “plotting the details of a post-Saddam government in Iraq, right down to the number of seats in a future parliament”. Similarly, in London the Foreign and Commonwealth Office created an Iraq Planning Unit at the beginning of 2003, headed by Dominick Chilcott, a 43-year old diplomat fresh from four years at UKREP in Brussels, and drawing in personnel from the Ministry of Defence and the Department for International Development. Its terms of reference, cited in the Chilcot Report, included the following objective:

The unit will aim to bring influence to bear on US plans by providing similar guidance, through PJHQ and MoD, to seconded British personnel working within the US military planning machinery and through the Embassy to the NSC and other parts of the US Administration.

However, this procedure for feeding advice from the UK to the US achieved very little. Cross told the Chilcot Inquiry, “I got no sense of UK pressure on the US; no ‘demands’ for clarity over the intended ‘End State’ or the planning to achieve it”. Dominick Chilcott would claim that “what mattered was influencing the American plan, and that was where our main effort was concentrated”. Cross, recalling a lunch with Rumsfeld and others, was considerably more downbeat when US leaders suggested that they would be greeted with relief by the Iraqi people, who would then turn to the business of building a state.

I argued that this was, perhaps, fine as a Plan ‘A’—but what was desperately needed was a Plan ‘B’ and a Plan ‘C’, and a recognition that what would probably emerge would be an amalgam of the last two. It was made clear that my views were not welcomed.

In the end, Cross’s predictions were proved most accurate.

The lesson of Iraq is this. The British government was determined to stay close to its American allies and to nurture the close relationship which Tony Blair had worked hard to establish, despite his potential points of difference with President Bush. In theory that was a sensible strategy: given the determination of the Bush administration to deal militarily with Saddam Hussein, to stand aside or take a radically different policy approach would simply have led Washington to shut us out, to ignore anything we might say.

But here is the difficulty: Blair sacrificed a huge amount of political capital—perhaps his reputation—to reassure the US administration that we were good friends and reliable allies. Some of the assurances he gave were so emphatic as to seem absolute and non-negotiable. As demonstrated at Camp David in February 2001, he was rewarded with warm words and flattery by the leader of the free world, and gained that ultimate prize of access. However, when matters came to a head, as the invasion approached and it became clear that there were issues on which the US was mistaken or under-prepared, the British government discovered that it had no influence. The White House and the Pentagon had already set their course and we were unable to dissuade them from it.

Britain conceptualising its place in the world

I have focused on the relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom in such detail at first because it is axiomatic of the spectrum of access and influence. Since the Second World War, successive British governments have tried to conceptualise ways in which the UK can punch above its weight partly because of its close bond with America but also bringing to bear its supposed stock of wisdom and experience from the long years and far reach of empire.

Harold Macmillan had framed this in an attractive way when he was minister resident in North-West Africa during the Second World War. His principal task was to engage with the American military leadership, particularly Lieutenant General Dwight Eisenhower who was Allied commander in North Africa from 1942 to 1944. When the future Labour cabinet minister Richard Crossman was assistant chief of psychological warfare at Allied Forces Headquarters in 1943, Macmillan explained the way in which Britain could exercise influence over the Americans.

We, my dear Crossman, are the Greeks in the American empire. You will find the Americans much as the Greeks found the Romans—great big, vulgar bustling people, more vigorous than we are and also more idle, with more unspoiled virtues, but also more corrupt. We must run AFHQ as the Greek slaves ran the operations of the Emperor Claudius.

It was a stereotypically Macmillan analogy: languidly sophisticated, superior, refined but shot through with bleak realisation that the best days had gone. On that last point it had some strength, but it was a hugely flattering way to see Britain’s role, and seriously underestimated both the sophistication of American politicians but also the quality and wisdom of British advice.

Although Blair would never have expressed it in the way that Macmillan did, there was an element of the same spirit in his approach and particularly that of Christopher Meyer in the build-up to the invasion of Iraq. Stay close, the thinking went, almost whatever the cost, and use that closeness to whisper in the American ear. Over Iraq, it is very clear now that the cost of proximity was extremely high, while what little was whispered in the ear was almost entirely ignored.

The desperately delicate trade-off between buying access and exerting influence is, of course, most acute with regard to larger, more powerful countries, and, for the United Kingdom, most pressingly applicable to the United States. But it can occur in bilateral relationships of a different balance. A strange and disheartening tale emerges from Rory Stewart’s Politics on the Edge: A Memoir from Within concerning his brief time as minister for Africa at the Foreign Office in 2017-18.

(Stewart had been an international development minister since 2016 but had suggested to Theresa May that he should be double-hatted at DfID and the FCO so that he could “think systematically about combining our different diplomatic, security and development projects”. His plan was not to merge the departments, though that would come to pass in 2020, but to create a “joint regional minister”. But he hoped and assumed that he would be given responsibility for the Middle East and Asia, regions he knew well and where he spoke three languages. The foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, decided instead he should take charge of Africa—“A Balliol man in Africa”—despite his protests that he knew nothing about the continent.)

Zimbabwe: the fall of Mugabe and potential British influence

In November 2017, the elderly, viciously autocratic president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, was deposed in a coup orchestrated by elements of his own ZANU-PF party and the Zimbabwe National Army. Stewart, although the FCO minister responsible, was informed straight away by officials but, finding out on Twitter, took himself to the Foreign Office where he found a meeting of FCO staff already underway under the guidance of the Africa director, Neil Wigan. Joining by video link was the ambassador to Zimbabwe, Catriona Laing; she had an aid and development background, first at the Overseas Development Administration when it was part of the FCO and then for the stand-alone DfID, and had been deputy director of the Number 10 Strategy Unit from 2001 to 2005.

Laing’s assessment of the situation was that Emmerson Mnangagwa, whom Mugabe had dismissed a few days before as vice-president, was likely to emerge as the next leader of Zimbabwe and (Stewart inferred) the UK should endorse him “and above all not alienate him by describing what had happened as a coup d’état”. The ambassador had cultivated a close relationship with Mnangagwa, despite criticism from white farmers, human rights activists, opposition politicians and Stewart himself. His nickname was “the Crocodile” for his political cunning, and, having been minister of state for national security from 1980 to 1988, with responsibility for the Central Intelligence Organisation, he was widely regarded as having a great deal of blood on his hands. His precise role in the Gukurahundi, “the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains”, a five-year genocide of the Ndebele and Kalanga people in Matabeleland which killed between 20,000 and 30,000, was fiercely disputed.

Mnangagwa was then 75 years old but, whatever his blood-stained past, he was not Mugabe, and Stewart acknowledged the potential power of the British ambassador being one of the few Western diplomats on friendly terms with the next president. He asked the meeting what conditions might be set in exchange for the UK’s support, suggesting that, to begin with, the opposition Movement for Democratic Change, led by the former prime minister, Morgan Tsvangirai, must be given a fair run in any election. Stewart relates that Laing replied “The opposition cannot win the elections”, then reiterated “Morgan Tsvangirai is finished—he cannot win the elections”.

Pressing on, Stewart suggested they draw up a list of dozen clear requirements for Mnangagwa. While encouraging officials to supply the detail, he suggested that expatriate Zimbabweans be allowed to vote, that voter registration be revised and that international observers be admitted. In return, the UK would persuade the IMF to provide an emergency loan to stabilise the Zimbabwean economy, which was in freefall, and increase bilateral development aid. There seemed, in Stewart’s view, to be an opportunity to help Zimbabwe make a major change of direction not only economically but also politically.

Laing is alleged then to have reported all of this, in unflattering terms, to the permanent secretary, Sir Simon McDonald. (He had been appointed to the job two years previously: in a brilliantly FCO piece of diversity, a white, middle-aged Cambridge graduate called Simon was replaced by a white, middle-aged Cambridge graduate called Simon.) The ambassador’s complaint was that Stewart was endangering the opportunity to create a more positive relationship between the UK and Zimbabwe through Mnangagwa by imposing conditions which he would either dislike or would simply not accede to. McDonald told friends, who then told Stewart, that he regarded the minister as an idealist—it was not intended as a compliment—and that he did not approve of junior ministers crafting their own foreign policy.

Stewart sought permission from the foreign secretary and the prime minister to fly to Harare. He issued a statement in which he recognised “an absolutely critical moment in Zimbabwe’s history” and spoke of “real hope that Zimbabwe can be set on a different, more democratic and more prosperous path”. But, as clearly as he could while adhering to diplomatic norms, he stressed that future developments had to be “in line with the Zimbabwean constitution and will be impossible without clear resolve from the incoming government”.

Laing organised a dinner for activists from Zimbabwean civil society. They were extremely positive about the prospect of Mnangagwa’s leadership, to the extent that Stewart, in what he admits was “a coarse breach of diplomatic protocol”, bet a pastor $50 that Mnangagwa would not allow free and fair elections. Afterwards, Laing told Stewart privately that he was being unhelpful in alluding to Mnangagwa’s murky past, and that there was little point in pushing the new president to make reforms. In his words, “I felt she was prizing our access, more than our influence”.

That is the absolute heart of it. Stewart met Mnangagwa, the first foreign minister of any country to do so, and he explained the requirements the UK had. Politely but firmly, Mnangagwa ignored him. When he returned to London, Stewart was explicit that “If we’re patient and if we’re careful, this can be a moment of change where Zimbabwe becomes the country its people and its many international friends want it to be”. But the message written between the lines, or at least the message he intended, was clear. Zimbabwe had been “one of the wealthiest countries in Africa. It has incredible human potential, a very educated population and fantastic natural resources.” But none of this was inevitable. There was an implied contract and it was an open question whether Mnangagwa would fulfil his part of it.

A few weeks later Stewart was moved to the Ministry of Justice as prisons minister. He was succeeded as FCO and DfID minister for Africa by Harriett Baldwin, a veteran banker at JPMorgan Chase & Co. who had been elected MP for West Worcestershire in 2010 and served as economic secretary to the Treasury (2015-16) and defence procurement minister (2016-18). Answering a parliamentary question a few weeks after her appointment, she reiterated that the government “welcome[s] President Mnangagwa’s recent statements on his desire to hold free and fair elections, including indications that international observers will be welcomed”.

Mnangagwa promised in an interview with The Financial Times that he would welcome election observers from the United Nations, the European Union and the Commonwealth, and expressed a keen desire to rejoin the Commonwealth (Zimbabwe had been suspended in 2002 then had withdrawn in 2003) and restore good relations with the UK. Elections were due no later than September 2018, and in March Mnangagwa indicated that the country would go to the polls in July. Morgan Tsvangirai, the opposition leader, had died of colorectal cancer in February 2018 and was succeeded as the MDC candidate by Nelson Chamisa, the 40-year-old former ICT minister.

Mnangagwa won the election narrowly, winning 51.4 per cent of the vote to Chamisa’s 45.1 per cent. ZANU-PF won 179 seats in the 270-seat National Assembly, with the MDC carrying 88. The election process had been peaceful but the MDC claimed that ZANU-PF and the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission had interfered with the results. There were claims that police officers had been forced to cast postal votes in front of their superiors, that there were voters registered who were purportedly in their 130s or 140s and that ZANU-PF transported voters to cast their ballots in districts other than where they lived. International observers had warned a few weeks before the election that the country was not yet ready for a free and fair contest. A post-election mission in September 2018 stated that Zimbabwe had not “demonstrated that it has established a tolerant, democratic culture that enables the conduct of elections in which parties are treated equitably, and citizens can cast their vote freely”. The United States declined to lift sanctions against the country, a State Department official saying “We want to see fundamental changes in Zimbabwe and only then will we resume normal relations with them”.

The government made major economic changes in September 2018, rebasing GDP and launching a Transitional Stabilisation Programme which prioritised “fiscal consolidation, economic stabilisation, and stimulation of growth and creation of employment”. Mnangagwa’s election slogan had been “Zimbabwe is open for business”, but the country had debts of $18 billion, and was in arrears by $1.8 billion. The domestic currency had long since been abandoned due to hyperinflation and the economy was running on a mixture of dollars, pounds sterling and South African rand, but cash was scarce. Unemployment was more than 80 per cent. Professor Mthuli Ncube, a former chief economist at the African Development Bank, Cambridge-educated and a former lecturer in finance at the London School of Economics, was appointed finance minister, which was welcomed by international observers.

There were signs of improvement despite the lack of political reform. Direct investment in Zimbabwe in 2018 increased by 134 per cent over the previous year. But there was little progress in political terms: riots following the election had been harshly suppressed, and fuel protests in January 2019 led to a brutal crackdown which saw more than 600 arrests and 12 deaths.

Did the UK miss an opportunity? Mnangagwa was re-elected president last August, and, in echoes of the 2018 contest, it was a narrow win (52.6 per cent against Chamisa’s 44 per cent) and the opposition MDC alleged widespread manipulation and fraud. International observers registered a number of reservations, including the banning of opposition rallies, issues with the electoral register, biased state media coverage and voter intimidation. Zimbabwe has been governed by ZANU-PF ever since independence in 1980, and there have only been three presidents: Canaan Banana (1980-87), Robert Mugabe (1987-2017) and Emmerson Mnangagwa (2017-). (The presidency was largely ceremonial under Banana, while Mugabe was prime minister, and it only became executive when Mugabe took over in 1987.)

The UK’s relationship with Zimbabwe is chequered. When Dominic Raab, then foreign secretary, announced sanctions on four senior members of the Harare régime in 2021, the reaction of The Zimbabwe Mail showed the gulf that existed: its headline ran “Colonialist Britain pushes to further isolate Mnangagwa’s regime”, and the sanctions were described as “a move seen in Harare as an unexpected kick in the teeth”. Interestingly, however, it also laid bare the extent to which Laing as British ambassador had been perceived as favouring Mnangagwa:

Laing worked frantically behind-the-scenes to support, profile and prop up Mnangagwa. She launched a daring campaign which included mobilising domestic, diplomatic, international and media support for him… In off-the-record meetings with editors, Laing made it clear that Mnangagwa was the British horse in the race to succeed the late former president Robert Mugabe ahead of his preferred candidate, then Defence minister Sydney Sekeramayi, not his wife Grace as most pro-Mnangagwa media claimed at the time.

The whole situation is eerily reminiscent of Iraq. The UK prized access above all, and the ambassador conducted herself in a way which, at the very least, raised eyebrows. In 2018, she was photographed outside Number 10 Downing Street wearing a scarf in the colours of the flag of Zimbabwe, a trademark of Mnangagwa, and the Zimbabwe opposition accused her of “putting lipstick on a crocodile”. Laing was also criticised for her failure to condemn the crackdown which followed the 2018 elections. The Times reported that “a senior MDC official described Ms Laing as ‘completely compromised’ over what he said was her tacit backing of Mr Mnangagwa”, and the same official noted when it was announced that Laing was moving on to be high commissioner to Nigeria, “We hope the Foreign Office is a bit more realistic about this new junta than the ambassador has been”.

Criticisms were renewed in May 2022, when Baroness Hoey recounted visiting Zimbabwe before the 2018 election on behalf of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, and her remarks were reported in The Zimbabwean.

We wrote of our disappointment and surprise that our ambassador at that time seemed to be so close to the ruling Zanu PF party… Many of us in the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Zimbabwe at that time tried to warn of the danger and futility of expecting change from Mnangagwa.

It is only fair to say that Laing, who is now head of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), has always denied any improper bias towards President Mnangagwa. To an extent, however, her intentions are a second-order issue; as a diplomat, she has to be aware that the perception of the host nation is at least as important, if not more so. It was plainly the case that there was a significant school of thought in Zimbabwe that Laing was too close to Mnangagwa—indeed, had been instrumental in his ascent to the presidency—and biased against Tsvangirai and the MDC.

Let’s look at the case of Zimbabwe as a matter of access and influence. Did the UK have access? Clearly so: Laing was regarded for better or worse as being close to the presidency of Mnangagwa and certainly exploited her status when Stewart visited Harare, allowing him to get a drop on the rest of the world in being granted an audience with Zimbabwe’s new leader. In part that is the function of a good envoy, though—as Laing found out—it comes with its own hazards.

It cannot have been easy to gain that access. Robert Mugabe had professed warmth towards the UK when he became prime minister of an independent Zimbabwe in 1980, even inviting the British to maintain a presence for a few years while the new government learned the ropes and, for a few months, appointing Lieutenant General Peter Wells, former head of the Rhodesian Security Forces, as chairman of the Joint High Command to integrate his former forces with the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army and the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army.

But he started to tack away from conciliation with the former colonial power. In 1992, when the provisions of the Lancaster House Agreement which protected the rights and property of the white minority, Mugabe passed the Zimbabwe Land Acquisition Act, which allowed the government to seize land at will; and the arrival of the Labour government in 1997 with its “ethical foreign policy” saw relations decline more steeply. In 2000, the UK imposed an arms embargo on Zimbabwe, and in 2002 Tony Blair campaigned to have Zimbabwe suspended from the Commonwealth. In the words of Patrick Wintour of The Guardian, “Mugabe never forgave him”.

But what did that access buy, when Mugabe was deposed and Mnangagwa replaced him? Certainly the public mood changed. “Our quarrel with Britain is over,” the new president declared, and in 2021 he visited the United Kingdom for the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. But Rory Stewart had said publicly in 2017 that Zimbabwe had to reform. Kgalalelo Nganje, writing for the Wilson Center in September 2023, argued that there had been virtually no significant institutional or political reforms in the years since the fall of Mugabe. Equally, there was little progress on promised economic reforms, which was and is holding up meaningful actions like debt relief and restructuring. Last month, the World Bank noted that, while Zimbabwe’s economy had performed relatively well since the Covid-19 pandemic, this was due to temporary external factors and there were still fundamental risks facing the economy. “Continued economic reforms will be essential to mitigate these risks.”

We have to conclude that the UK has exerted very little influence over President Mnangagwa. Given our prized position when he seized power in 2017, it is difficult to point to anything he has done, any policy he has pursued, that can even partially be ascribed to British influence. Yet, as with Iraq, there has been a price: the UK is seen by elements of the Zimbabwean opposition as less than an honest broker, a government which is not only favourable to Mnangagwa but willing to overlook serious shortcomings in areas like human rights.

Conclusion

These are only two examples, and they both prove the negative case for the notion of a balance between access and influence. But they are sufficiently different—one with the world’s superpower whose friendship we court constantly, the other with a former colony in Africa which is our 112th-largest trading partner—that we can distill some observations from it.

The idea that making some ethical or reputational sacrifices to win a place in a foreign country’s counsels makes sense on an obvious level. It goes back to the foundations of modern diplomacy, when in 1604 Sir Henry Wotton, James VI and I’s envoy to Venice, famously said that “An ambassador is an honest gentleman sent to lie abroad for the good of his country”. The cynical sense of give and take seems realistic to us, on the basis that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

For some countries the trade-off is obvious. During the Cold War, the United States backed all sorts of unsavoury régimes, from Chile to, for a time, Ba’athist Iraq, for purely strategic reasons: everything was part of the struggle against Communism, and everything was subordinated to that. For the United Kingdom, it is not so clear-cut. It is fashionable to say, with regret or glee, how little weight we carry in the world, and, for some people, that is many times more true since Brexit, but it is a rather British piece of self-effacement: whatever else has happened, we remain either the fifth or sixth biggest economy in the world, we are a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, we are a nuclear power, London is one of the world’s biggest financial centres and we are home to some of the most influential weapons of soft power in the world.

But, as was at least the subtext of Harold Macmillan’s ‘Greeks and Romans’ analogy, we are no longer so powerful that we can achieve our ends by force alone. We must be skilled diplomatists. That inevitably draws us into the world of murky compromises, of doing what we must rather than what he ought or would like to, of having a sufficiently long spoon to sup with a variety of interlocutors. The question then becomes whether we are good at it.

I could explore the performance and reputation of the UK’s Diplomatic Service at great length, and I will, at some point. In 2016, former ambassador Tom Fletcher, whom I like and rate very highly, produced a review of the Foreign Office entitled Future FCO which is well worth reading. To some extent, the shortcomings of the FCDO (as it now is) and British diplomacy in general can be traced in its imprints of the review’s recommendations. A 2022 report by the Institute for Government suggested the FCDO’s regional focuses were uneven, that too few UK-based civil servants were deployed abroad and the department did not communicate as well as it could with other parts of Whitehall. The Foreign Office re-established an in-house language training capacity in 2013 after it had been outsourced in 2007, and a training institution, the International Academy, was established at the same time. The House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee noted in 2018 that on language training “there is a long way to go”. It also warned that “goals should not be achieved by simply lowering the standards of language proficiency that officers are expected to reach”.

Another report from the Foreign Affairs Committee in 2020 concluded that British foreign policy “lacked confidence”, and “appeared less ambitious and more absent in its global role”. It spoke of “the persistent problem that Britain abroad is less than the sum of its parts”. This observation, I think, strikes at the heart of this question of access and influence. Diplomats, hard-working and able, do manage to find ways to connect with foreign governments to a degree which perhaps eludes some other countries, but when the time comes at which an outside observer might expect a quid pro quo to come into play, where our access might be leveraged to create policy changes by our allies, there seems to be a collapse of optimism. It may be unfair to take Catriona Laing as an example, but the portrayal which Rory Stewart gives is that she had carefully curated access to Emmerson Mnangagwa, but could not countenance potential offence, or loss of access, by demanding concessions he would not want to grant. That is understandable on a human scale, but it makes the process literally pointless.

If I have demonstrated that in the past the United Kingdom has given away too much to achieve access which it has then been able or unwilling to use to exercise influence, what is the message for the future? Overwhelmingly my plea would be for realism. I seem to spend a lot of time in a number of contexts now talking about intellectual honesty, realism, facing up to facts. But that must be overwhelmingly necessary in this context. If the UK, whether at Whitehall level or in an individual diplomatic mission, is going to make compromises and sacrifices—essentially, do things it would not normally do—to gain the confidence and trust of an ally, it must be brutally honest with itself about those compromises. We need not excoriate ourselves but equally we should not congratulate ourselves for our virtue when we are doing things which are necessary but perhaps not admirable.

The pay-off is much more important. If we have gained this close relationship, it must be for some purpose. There must be that quid pro quo. In short, we cannot be so afraid to damage or lose our access that we do not use it for any gain. (There is a strange parallel here to a problem in the defence world, which I wrote about and called “Tirpitz syndrome”, in which we procure assets which are so expensive and so valuable that we are then reluctant to deploy them.) And if we find, as we did in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, that our influence is illusory, that we cannot in fact change the course of events, that must be something from which we learn. In the end, this is all about the United Kingdom’s reputation on the world stage. There is something worse than looking weak: and that is looking like a fool.

Bush junior,draft dodger. Blair, never worn uniform in his life. Both poorly advised, acted in haste and let sentiment override cold fact. Never start a war unless you have no choice. They have uncertain outcomes.