The Iraq War: the Left's obsession

It is nearly 20 years since we participated in military action against Saddam Hussein; why are some people still fixated with the conflict?

It still astonishes me, though it shouldn’t, when young people (by which I mean under, say, 30) talk about politics in any form and wheel out the phrase “the Iraq War”. Operation Telic, as the British called our military activity in Iraq, began nearly 20 years ago now, and concluded, after a rather weedy deflation, in 2011. 179 armed forces personnel died, each a tragedy but not, overall, a devastating butcher’s bill, and the monetary cost is estimated at £9.6 billion (to provide a comparator, the Ministry of Defence spends around £42.4 billion each year).

The Iraq War is, however, totemic for those on the Left. For them, it is forever the legacy of Tony Blair, obscuring any of his achievements in government which even I, as a free-market Conservative, will admit are substantial. Labour’s most electorally successful prime minister is for them simply the man who took Britain into war, with disastrous consequences.

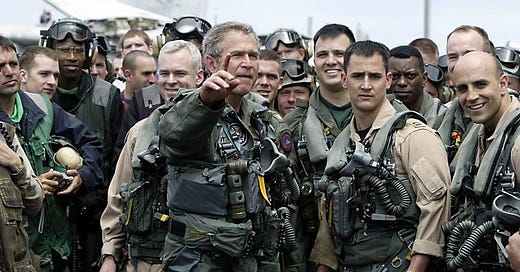

That it was disastrous is an argument most have to accept. Although the initial military phase of the operation, which was over within weeks, was almost entirely successful, after that almost nothing went right. Planning for the post-conflict phase was woefully inadequate, and there is some truth in the caricature that the British, wise but modest in numbers, warned the dominant but brashly overconfident Americans that the coalition needed to think more carefully about what would happen after the fall of Saddam.

(I can happily pick apart the invasion and occupation of Iraq in some detail, pointing to mistakes and missed opportunities, but that will have to wait for another time.)

I must confess an unvarnished failure here. I was a postgraduate student when the war began, fascinated by politics and fairly knowledgeable about it; two years later I started working in Parliament. In St Andrews, we were not prone to marches or protests, and had perhaps a more right-wing student body than many institutions, particularly given our substantial cohort of US students. Many were attracted by the School of International Relations, which is globally renowned and has consistently hosted some of the best scholars in the world. There was, therefore, no shortage of expert and semi-expert analysis.

Despite or because of that, I simply did not see the significance of the war at the time. I recognised that there was substantial opposition, and watched with curiosity the enormous Stop the War Coalition march in February 2003 which attracted, at conservative estimates, 750,000 participants. But I was old enough and politically aware enough to remember the Countryside Alliance march in 1998, protesting against the ban on hunting with dogs, and knew that it had mustered an impressive 250,000. I knew, too, that the Suez War had resulted in major demonstrations and bitter political controversy, as well as the fall of a prime minister, but had blown over within a few years as Harold Macmillan had steadied the ship.

In short, I thought there would be a flurry of outrage, perhaps some electoral backlash against the Labour Party at the general election due by 2006, and then we would return to business as usual. After all, the House of Commons had approved the military action 412 votes to 149, the official opposition rowing in behind the government and only Robin Cook’s resignation and powerful jeremiad from the backbenches making much real difference. (Yes, Tony Benn had spoken passionately against war too at the February march, but he had stepped down from the Commons in 2001 and was becoming a predictable left-wing activist whose views on almost any issue could be foreseen with ease. He no longer had much sway.)

For a while, it looked like I might be right. Blair was returned for an unprecedented third term in 2005, its majority reduced to a more-than-respectable 67 from the dizzy, hardly believable heights of 1997 and 2001. Yes, the Conservative Party was still struggling badly, Michael Howard bringing some rigour and professionalism to the leadership but achieving no traction with the electorate; yes, Labour only won 35% of the popular vote, down from 40% in 2001. But it was by any standards a handsome victory, Blair still had British politics at his feet (the brooding and dissatisfied Gordon Brown notwithstanding) and it was difficult to see, two years after the invasion, what serious price the government or the prime minister were paying for their decision to go into Iraq.

In purely parliamentary terms, I think I was proved mostly correct. Brown, who had shown no signs of unease about the conflict, became prime minister in 2007 without a contest, and the Conservatives came out on top in the general election of 2010 despite having supported the war—their leader, David Cameron, had voted for military action but had only been a backbencher in 2003 and had not been in the spotlight. The Conservative Party has continued to be successful since, and is in its thirteenth year in power.

Perhaps the Liberal Democrats proved where I was wrong. They had opposed intervention in 2003 and had used their anti-war stance as a leading card since then. (In truth, they were opposed in qualified terms: Charles Kennedy, their already-ailing leader, had laid out conditions under which they would view intervention as acceptable.) Nick Clegg, who had become leader in 2007, was felt to have done very well in the pre-election leaders’ debates (“I agree with Nick”), and the party roared to its best result since before the Second World War, taking 57 seats. This high tide was enough to give them the decisive power in a hung parliament, and Clegg agreed a coalition deal with Cameron, becoming deputy prime minister.

But here we were, in a sense, the trajectory of our national politics not discernibly affected by the war in Iraq which, by 2010, was winding down in terms of the British commitment (though the security situation in Iraq remained dire). My antennae had been as sensitive as ever, I flattered myself, and had reinforced my ability to read political tea leaves.

As I say, I accept that I could hardly have been more wrong. In 2010 it was not obvious that substantial parts of the Labour Party would, with rather more conviction than St Peter of his Messiah, deny Tony Blair and all his works. Of course there had always been a left-wing faction which had never accepted Blair, deciding as early as his revision of Clause IV of the party’s rule book in 1995 that he was a crypto-Tory, a middle-class Nicodemite and in general terms a slippery salesman and definite wrong ’un. There were irredeemable refuseniks like Jeremy Corbyn (a leader in waiting!), who voted against his party whip 428 times between 1997 and 2010, but these people were on the fringes of Labour.

Yet the matter of the war was only becoming more powerful. That had always been a certain sort of activist, pure of thought and usually contemptuous of realpolitik, who would reach for the phrase “illegal war” to prove that their target—usually Tony Blair or his adherents, but sometimes Conservatives, the Establishment, neo-conservatives, senior brass or diplomats—had not merely made a miscalculation in 2003 but were wholly inadequate in moral terms, bare hollow shells of humanity who, by support for this one cause, had effectively ruled themselves out of participation in decent politics.

I have my own views on the legality or otherwise of military action against Iraq in 2003. While I accept that the government (like the Bush administration in the US) made clumsy mistakes and told frank untruths to justify the invasion, I think it is at least arguable that it was legal, I am adamant the debate is not a slam-dunk, and I regard the authority of the United Nations sufficiently lightly that I am happy to lean quite heavily on the military, political and ethical necessity to displace Saddam Hussein as at least equal in force. But that is another debate, and certainly not one that the “Illegal War” brigade will countenance.

Now that I’m in my mid-40s, I have relatively little contact with undergraduates and their age-mates. But I do observe, outwardly mildly but archly in my mind, that a first-year student today was born in around 2004, after the military phase of the invasion and certainly far too late to have any conception of the war as a current issue. For them it is an historical event, something their parents might talk about, yet their opposition to it burns with a fire I wish young people could feel for history more generally. However blinkered and dogmatic they may be, I would love to have a class which argued over the English Reformation with that kind of passion (though they would need to have done much more reading).

This fact was brought home to me with particular force a few years ago, when the film Official Secrets was released. The film, a true story, deals with a GCHQ translator, Katherine Gun, who leaked to The Observer classified information which revealed that the US had been exerting improper influence on other delegations at the UN to support a resolution on Iraq. It is a decent film, with some fine performances, and doesn’t present the story in quite the hectoring or partisan way I had rather expected. The company I was working for at the time was helping to promote it, so I went with some of my colleagues to a screening at the now-defunct H Club in Soho.

When we emerged from the theatre, we all more or less agreed that it had been a respectable effort and we had largely enjoyed it. I said in passing that it had been a little free with the facts to present a solidly moral anti-war case but that I had rather expected that, given that I had supported the war and still thought it had been the right decision. My colleagues, aged from their early 20s to their early 30s, looked at me with uncomprehending horror (even more so than usual).

I instantly realised two things. The first was that, for them, the Iraq War was, as I mentioned above, an historical event, something from their childhood. The second was that opposition to the war was so ingrained in them that they simply took it for granted in a civilised person, like a belief in democracy and a disdain for Nazism. They had no conception of it as a live issue, politically charged but by no means settled, on which people had widely varying views and which a lot of otherwise-normal citizens had felt was a necessary reaction to the Ba’ath gangsterism of Saddam.

I didn’t press the issue. I don’t like falling out with friends, I recognise that a lot of people find it hard to separate political disagreement from personal rancour, I was tired and anyway I already had a reputation as the office Tory, an object of curiosity but some affection: one colleague, who had worked for Jacinda Ardern in Wellington, told me I was the only Tory she liked. I believed her, and was, in a weird way, flattered.

Here were pleasant, friendly, intelligent young people, leftward-leaning in politics, certainly, but not Marxist sectaries, who regarded opposition to the war in Iraq as an article of faith. And I don’t think they are unrepresentative. There is a large body of opinion out there, mainly but not exclusively young, which never imagines or conceives that the war was other than wrong; not just a strategic mistake (though in that regard I have some sympathy) or a political miscalculation, but a great, rending ethical failure, of our government, our institutions and our whole society. It has a moral force of no other individual piece of policy of which I can think: even some of the hardest-edged elements of Thatcherism do not seem to provoke the reflexive horror which Iraq does.

At some point I will write further on the effect this has had on the Left, both in terms of foreign policy and wider politics. Here I simply want to mark it and note that it is an extraordinary thing. And, perhaps, wonder where this will end. The authors of the war, in Washington and London, have now left the stage, though Tony Blair, essaying as an elder statesman, still reminds the Left of their great hatred. Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, have all gone, some on that final journey. In Westminster, Blair, Brown and Straw are absent—no peerages for them, for varying reasons—while Cook and Benn are dead and Clare Short, whose opposition to the war proved not quite absolute enough to prise her out of ministerial office at the time, is hardly remembered. Jeremy Corbyn keeps the faith but is ageing and has left front-line party politics (which he never seemed to like).

This is, to try to conclude, something of a mystery to me. I take a rather jaundiced view of those whose weltanschauung is still dominated by the Iraq War, because I distrust all monomania (like batty old (Sir) Tam Dalyell’s obsession with the sinking of the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano during the Falklands War, or the gruesome Norman Baker’s fixation with the death of Dr David Kelly in 2003). But, as I say, I will dwell on this effect of this obsession another time. My question, posed because I cannot answer it myself, is why the war has assumed this totemic importance.

Answers on a postcard, please. I don’t believe it’s because the intervention of Iraq was uniquely egregious in global politics, because it really wasn’t. There must be something else. I want to be kind, and I’ll try to be so for now. But not forever.