Yes, deputy prime minister: the development of the premier's stand-in, part 1 (1923-97)

A number of politicians have carried the title "deputy prime minister" but it can mean very different things depending on who bears it

It is a peculiarly British attitude that allowed our constitutional mavens for many years to agonise and argue at length over the idea of a “deputy prime minister”. Many countries have a recognised “number two” with varying duties, from the US vice-president to the German vice-chancellor (who is offically known as “deputy” or “Stellvertreter”), and this is not regarded as problematic or presumptive. In our connoisseur’s constitutional arrangements, however, it is a thorny issue.

This subject seemed appropriate for exploration because the current DPM, Dominic Raab, is weathering a certain degree of scandal at the moment, standing accused of several instances of bullying towards staff both in the Ministry of Justice, where he has now served three separate times, and at the Foreign Office. For the accuracy of the accusations I cannot speak and wouldn’t presume to do so. The charges are being pursued through the appropriate channels and we should all await the result of that process. But if the worst were to happen, then Rishi Sunak could again be forced to face the issue of a deputy and substitute.

To avoid producing another overweight essay, I have decided to split this in two: the first will look at deputies from the early years of the 20th century until the Blair landslide of 1997, in which time the title was a rarity. In the second part, I’ll explore the years since 1997, when there has been a deputy prime minister more often than not and leadership elections have featured the very un-British notion of “joint tickets”.

Although the title has been awarded more often than ever in recent decades, it is important to remember that there is no necessity to have a deputy prime minister. It is a title or designation rather than an office, though it is sometimes paired with a sinecure which makes it to all intents and purposes a full-time role. Equally it can be combined with a major executive cabinet position and serve mainly to indicate the importance of the office-holder.

For many years, at least until the Second World War and arguably until the 1960s, it was widely argued that there could not be an official designation of “deputy prime minister”, as some thought this title carried with it an implication of being next in the line of succession to the premiership, which implication infringed on the sovereign’s ability to choose a prime minister of his or her own choosing. I have never found this a persuasive argument. Firstly, being “deputy” does not automatically carry the right to succeed; the pope is the “vicar of Christ”, his stand-in on Earth, but no-one imagines that the pope will become Christ if there is ever a vacancy. In any event, the role of the monarch in selecting the prime minister is now almost entirely a formality, as he merely endorses the choice of the governing party by whatever mechanism it prefers. The last time the sovereign might have had any leeway at all in the selection of the prime minister is at the latest 1957, and arguably 1931. The Labour Party has elected its leaders since 1922, and the Conservative Party followed suit in 1965.

This is not to say there was no way of someone else standing in temporarily for the prime minister until after the Second World War. When Andrew Bonar Law began to decline with the throat cancer that would soon kill him in the beginning of 1923, it was agreed that Lord Curzon, the foreign secretary, would carry out any functions that were required. When Stanley Baldwin joined the Prince of Wales and Prince George on a royal tour of Canada in the late summer of 1927 to celebrate the diamond jubilee of the confederation, he asked his foreign secretary, Sir Austen Chamberlain, to act in his stead when necessary. And when Ramsay MacDonald visited the United States in October 1927, the chancellor of the exchequer, Philip Snowden, minded the shop at home. But these figures were not given new titles, merely described as “acting for the prime minister”.

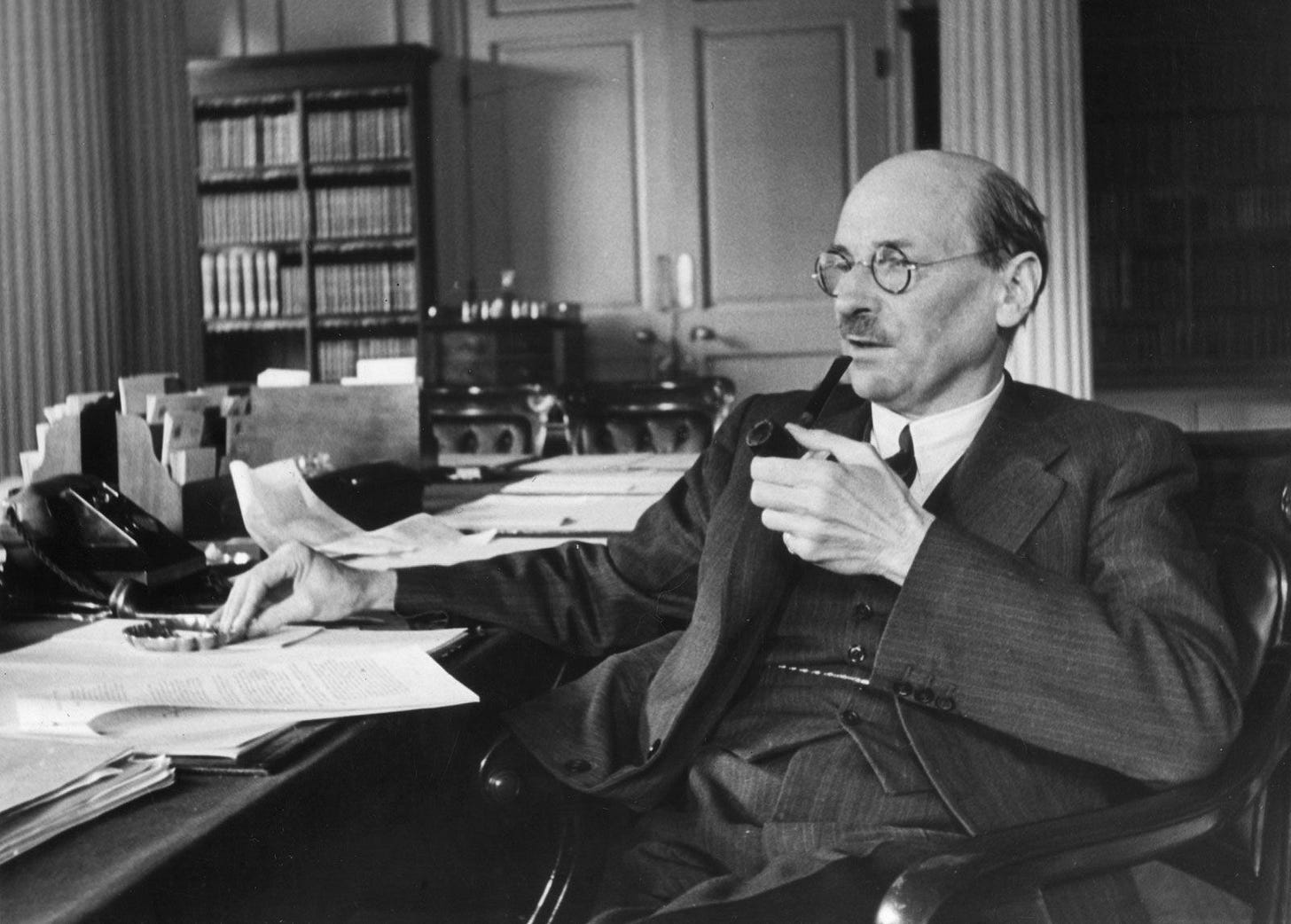

One useful role of DPM titles can be in coalition governments, when they can be used to recognise the leaders of smaller governing parties. This would become true in the 2010s. But it was first brought under consideration during the Second World War. During the National government of 1931-40, there was no formal deputy, although Baldwin was the effective number two while MacDonald was still in office in 1935. In 1942, during the all-party coalition government, the title of deputy prime minister is first recognised in the Official Report (Hansard), when Churchill, describing the restructured war cabinet, informs the House that “The new War Cabinet consists of seven members, of whom three have no Departments. One is Prime Minister, one is Deputy Prime Minister with the Dominions Office, and one is Foreign Secretary”. In this case it was the Labour leader Clement Attlee who became DPM, serving with quiet diligence and determination until the coalition broke up in May 1945.

The description of Attlee as deputy prime minister was wholly appropriate. As well as being the leader of the second largest party in the Commons, Attlee deputised for Churchill in the House of Commons, at cabinet and in cabinet committees when the prime minister was absent, and, while he spent a few months as dominions secretary in 1942-42, after September 1943 he chaired the Lord President’s Committee, which dealt with home affairs, including the economy. This was supposed to free the prime minister to focus on defence and foreign relations, but allowed a diligent man like Attlee to have a great deal of influence in small but lasting ways. He also had many opportunities to act in Churchill’s place as the prime minister went abroad for major summit meetings like Casablanca, Tehran and Yalta.

In one sense, though, Attlee was not deputy prime minister, and that is in terms of a line of succession. Given the frequency with which he travelled, Churchill had several discussions with the King during the war to discuss what should happen if anything happened to Churchill while he was abroad. If he was travelling without the foreign secretary, it was assumed that Anthony Eden, the Conservative heir apparent, would replace him; this was confirmed by letter to the King in June 1942 at the latest. But Churchill and Eden sometimes out of necessity travelled together, for example to Cairo in 1943 and Moscow in 1944. In the event of their both perishing, Churchill told George VI that he should invite the chancellor of the exchequer, Sir John Anderson, an independent MP for the Combined Scottish Universities who had held several senior posts in the civil service, including governor of Bengal and permanent secretary at the Home Office, before becoming an elected representative in 1938.

The title lapsed when Churchill formed his caretaker administration in May 1945, though the foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, was almost universally recognised as the second man in the Conservative Party and therefore the government. During Attlee’s administration (1945-51) this period of desuetude continued; Attlee would have found awarding the title far more divisive than any good he may have had from a formal deputy, as the pack of big beasts—Morrison, Bevin, Dalton, Cripps, Bevan, Gaitskell—jostled for advantage and worked through their individual psychodramas. Morrison, as leader of the House of Commons and then as foreign secretary, acted in some ways as Attlee’s stand-in, chairing cabinet when the prime minister was absent and deputising for him in the Commons when necessary. Paying tribute to Morrison after his death in 1965, Harold Wilson referred to him as “deputy prime minister”, and that description had been pinned on him by a Conservative MP in a debate in 1947, but otherwise the title was not used in official documents.

When Churchill returned to Downing Street in 1951, he sought to formalise the position of deputy prime minister and intended, of course, to award it to his now-impatient heir Anthony Eden. The foreign secretary’s impatience with Churchill was an open secret, even sometimes a subject of teasing, but there is no reason to think at this point that Churchill intended to frustrate his deputy. Nevertheless, when the prime minister submitted the idea of Eden as foreign secretary and deputy prime minister to the king, the sovereign would have no part of it, and the latter designation was scratched out. George VI felt that this was an attempt to limit the Royal Prerogative and force his hand in selecting a new premier if necessary. This was an excessively fussy reading of the situation, but the king was ill and declining fast: he had cancer, and his left lung had been removed the month before the new government was announced, and within four more months the king was dead of coronary thrombosis.

Eden succeeded nonetheless when Churchill retired in April 1955, and there was no suggestion that the queen might have sent for anyone else. Eden was still in his fifties but his health had been broken by a botched bile duct operation in 1953. It was characteristically witty and cruel of Harold Macmillan to say of the succession, many years later, “The trouble with Anthony Eden was that he was trained to win the Derby in 1938; unfortunately, he was not let out of the starting stalls until 1955”. Eden made no attempt to appoint or designate a deputy either as replacement or intended successor. Of course he had no idea at first that his premiership would be so short and he would be out of office by January 1957, but he was also, for a short time, the supremely dominant personality in his cabinet. Macmillan and Rab Butler were still adjusting to their great offices of state, and Selwyn Lloyd, appointed foreign secretary at the end of 1955, was very much Eden’s creature. Most of the ministers of Churchill’s generation had fallen away, and the only person with a stature even approaching Eden’s was his old friend of the pre-war days Bobbety Salisbury, leader of the House of Lords and an increasingly reactionary force in Conservative politics.

There would not be a deputy prime minister again for another seven years. When Eden resigned in January 1957, the succession was clearly a two-horse race between Butler and Macmillan. Butler was in many ways the senior figure: he had more experience in government and had been appointed chancellor of the exchequer in 1951, when Macmillan was made only minister of housing. But Macmillan was by far the more cunning, and managed to have seemed hawkish on Suez before the conflict began, then one of the earliest proponents of withdrawal when the whole adventure turned sour. Eden made no recommendation to the queen on his successor, so Salisbury, as a senior minister clearly not involved in the contest, polled the cabinet one by one. He asked them a simple question, immortalised by his speech impediment: “Well, which is it, Wab or Hawold?” Three at most declared for “Wab”; Macmillan was summoned to the Palace.

Butler was very disappointed. He had been seen as the next big beast in the Conservative Party throughout the 1950s, and worked hard to help the party’s revival after 1945. Asked by a photographer what he was doing shortly after he found out Salisbury’s verdict for Macmillan, he replied “I’m taking a walk. The best thing to do in the circumstances.” But he put a brave face on it, as he did on almost everything. Paying tribute to him in the Commons after his death in 1982, Thatcher said he did not allow the reverse “to diminish his zeal or his work for the cause which he served throughout his life”.

Rab was a good loser. But he also had to be fitted into Macmillan’s cabinet. He wanted very much to be foreign secretary, having been under-secretary of state under Lord Halifax (and therefore the only Commons minister) from 1938 to 1941. That was not to be at this point: Macmillan instead made him home secretary to replace the departing Gwilym Lloyd George, and he retained his existing post as leader of the House. In this latter capacity, he carried out some of the duties of a deputy prime minister; he spoke for Macmillan in the Commons when required, and minded the shop when Macmillan went abroad. Most famously this fell to him in January 1958 when the whole Treasury team resigned just as the prime minister left for a tour of the Commonwealth. Macmillan plastered on his face of Edwardian insouciance and told the press, “I thought the best thing to do was to settle up these little local difficulties, and then turn to the wider vision of the Commonwealth.”

In the summer of 1962, Macmillan, feeling the government was becoming stale, decided to carry out a substantial reshuffle and remove several ministers from the cabinet. His initial plan was to wait until Parliament returned from the summer recess in October, but Rab’s notorious indiscretion forced him to rush: on 11 July, Butler had lunch with Lord Rothermere, owner of The Daily Mail, and “let slip” Macmillan’s plans for a major reconfiguration. The following day the story was on the front page under the headline “Mac’s Master Plan”. The prime minister had no choice but to start firing ministers straight away.

Did Rab leak the notion of the “Night of the Long Knives” deliberately? Macmillan thought so. It is not impossible, but it is no less likely that it was an accidental indiscretion, of which Rab was often guilty. In any event, it rebounded on him. Part of the reconstruction involved moving him from the Home Office—which after five and a half years must have been a relief—but, rather than giving him another major position, Macmillan awarded him the new title of “First Secretary of State” which, he said, would be the equivalent of deputy prime minister. He was also given ministerial responsibility for the now-forgotten Central Africa Office, created to manage the turbulent affairs of the Central African Federation. If Rab was told he was the equivalent of deputy prime minister, the press were given a slightly different nuance, which was that he would act as deputy prime minister, which, arguably, he had since 1957. Macmillan also stated that “This is not an appointment submitted to the Sovereign but is a statement of the organisation of government.”

The supposed restriction on the royal prerogative of the use of the title was proved unfounded in 1963: when Macmillan resigned, he was determined that Butler would not succeed him. Eventually he alighted on the Earl of Home, foreign secretary, as a viable candidate, and Rab was outmanoeuvred. When the new cabinet was formed, Butler finally went to the Foreign Office, and the idea of a deputy prime minister was quietly dropped.

The title of deputy prime minister was left to gather dust for the next 16 years. Harold Wilson was too wily a fox to give any member of his cabinet such a fillip—though he did use the title of first secretary of state for George Brown, Michael Stewart and Barbara Castle—while Edward Heath had no real trusted lieutenant, though Willie Whitelaw, leader of the House of Commons then the first Northern Ireland secretary, began to assume that role. When Margaret Thatcher upset the conventional wisdom and snatched the leadership of the Conservative Party from Heath in 1975, Whitelaw, who had stood against her but been handily defeated, decided to pledge his unshakeable loyalty to her and was named deputy leader of the opposition. After the general election in 1979, Thatcher made him home secretary, as expected, and treated him as deputy prime minister, but he was never given that title formally (though it was frequently used in the media). In practical terms, until 1983 he stood in for her at Prime Minister’s Questions and was her closest adviser, both a sounding board and, in the early days, a kind of talisman against the Heathite wets (of whom he had very much been one).

Whitelaw was Thatcher’s loyal deputy as home secretary (1979-83) then as leader of the House of Lords (1983-88). Famously, at a dinner for his retirement, she remarked that “Every prime minister needs a Willie”. It was almost certainly the funniest thing she ever said, though it is wholly possible she did not understand the joke: it is a little risqué for her and she had almost no sense of humour at all. But, innuendo aside, she was right that she, at least, had needed Whitelaw. It is hard to remember or imagine now how revolutionary Thatcher’s gender was in a party leader, let alone a prime minister. (It remains a great irony that she only ever appointed one woman to her own cabinet, Lady Young, from 1982 to 1983: sisters were left to do it for themselves.) But in the Conservative Party of the late 1970s and early 1980s, she was marked out by her class too. She came from at-best-middle class origins, her father, famously, a grocer, mayor and alderman, but had married a wealthy businessman and was financially comfortable by the time she joined the House of Commons. Importantly, but often forgotten, she was by background a non-conformist. That mattered more than people realise.

At that time, although the party was widening its base in terms of activists and members, the Conservative Party still had a heavy dose of aristocracy at its top. Thatcher was both provincial and grammar school-educated, which an Oxford degree could not quite wash away. Even her close supporters were from different backgrounds. Sir Keith Joseph was a peculiar admixture, a wealthy, public school Jewish intellectual who, because his father had been lord mayor of London, was a second baronet. Sir Geoffrey Howe came from a professional legal family and had attended Winchester and Cambridge. Airey Neave, her private secretary who was murdered by terrorists just before the 1979 election, came from a prosperous merchant family ascended to the baronetage, and had been to Eton and Oxford.

Whitelaw gave her cover from this. He came from a landowning Scottish family based in the east Highlands, characteristically having not a trace of a Scottish accent, and was educated at Winchester and Cambridge. He had ‘a good war’ with the Scots Guards, winning the Military Cross, before he left the Army in 1946 to look after family estates in Lanarkshire. He was not an intellectual but he was sharper than he appeared, concealing it behind a bluff, clubbable exterior. And he could defend Thatcher from every side on which she was weak: aristocratic where she was bourgeois, Anglican where she was originally Methodist, an apologetic wet where she was the ultimate dry, a man, a former soldier, a conciliator rather than one who craves and argument. In some ways, Whitelaw’s appointment was a very British equivalent of balancing the ticket in an American presidential election. He may never have had ‘deputy prime minister’ written on an official document, but he was perhaps the most effective and vital deputy certainly since the war, and perhaps of the century.

Whitelaw, 69, suffered a stroke at a carol service before Christmas 1987. Although the affliction was mild, it encouraged him think about his future, and he retired in January 1988. If he had been invaluable in her early days as prime minister, Thatcher relied on him less by the beginning of her third parliament, for better or worse. He was, however, irreplaceable, personally and institutionally. His place as leader of the Lords was taken by Lord Belstead, a steady-as-she-goes minister who had served under Thatcher at the Department of Education and Science in the early 1970s. He had, it was said, a character “as steadfast as a Suffolk punch”, and was not in Whitelaw’s league: but then, no-one expected him to be.

Thatcher appointed another deputy in the summer of 1989. Shaking up her cabinet team substantially, she decided to move Sir Geoffrey Howe from the Foreign Office, where he had been for six years, and install the young and barely known John Major as his replacement. There was an argument that Howe had been foreign secretary for long enough and a change was due, but he liked the job (and Chevening, the country house which came with it) and was dismayed to move. Thatcher presented him with a choice: he could become home secretary (Douglas Hurd had already served four years), which seemed fitting for Howe as a QC and a former law officer, or he could become leader of the House of Commons in place of John Wakeham. Howe chose the latter but insisted he must also be deputy prime minister; if that was not possible, he would prefer to leave office altogether.

The Westminster jungle could decode the move: Thatcher’s primary motivation had been to dislodge Howe from the FCO, and the rest had been improvised compensation. Perhaps accepting the Home Office would have produced a different impression, and the image of a new challenge back in domestic politics, but the loss of a department of state looked like a demotion. The illusion of the post of deputy prime minister was shattered within 24 hours. The Downing Street press secretary, Bernard Ingham, briefing lobby journalists the morning after Howe’s new appointment, remarked that the position had “no constitutional significance”. Whether this was an overdose of Yorkshire bluffness on Ingham’s part or a deliberate attempt to diminish and undermine Howe is unclear, but effect was the same. It exposed that Howe was in no way Whitelaw’s spiritual or operational replacement.

The difference between Whitelaw and Howe neatly illustrates the range of possibilities for the deputy prime minister in the Whitehall system. Whitelaw, who had been runner-up to Thatcher in the 1975 leadership election, moved himself immediately out of any contention to replace or succeed her, and instead installed himself as her loyal adviser and candid friend. Howe had once been considered papabile, if not necessarily at the front of the conclave, and, 14 months younger than Thatcher, there could have been scenarios in which he might have taken the reins from her. But by 1989, when Thatcher was approaching 64 and Howe was 62, that was no longer likely. Yet their close policy relationship and the personal connection between them had all but collapsed, she now visibly bullying him in cabinet and he stubbornly stoical to the embarrassment of others; so there was a no chance either of Howe being a supporter and adviser either, although perhaps by late 1989 she needed that more than ever. Absent those two roles, his position as deputy prime minister really was the hollow crown which Ingham had carelessly or maliciously suggested.

Howe’s resignation in November 1990 and the devastating Commons speech which followed it led to Michael Heseltine’s leadership challenge, Thatcher’s resignation and the eyebrow-raising arrival of John Major in 10 Downing Street. The new prime minister did not at first name a formal or even informal deputy. In an inversion of the unhappy tenure of Geoffrey Howe, he tried to recreate Whitelaw’s function without giving it the form of DPM, looking for a heavyweight “fixer” who could support him behind the scenes and generally add ballast to his leadership (Major was at that time the youngest premier since Lord Rosebery and had only three-and-a-half years in cabinet).

His first choice was the home secretary, David Waddington, a no-nonsense Lancashire QC who had been chief whip from 1987 to 1989. Major, thinking him “a wise old bird”, gave him a peerage and installed him as leader of the House of Lords, Whitelaw’s old post, and chairman of the cabinet’s home and social affairs committee. But Waddington never quite made it work. For all that he was tough and practical, he could not charm their Lordships, who were fiercely opposing what became the War Crimes Act 1991. It was passed using the provisions of the Parliament Act 1949, the only occasion on which a Conservative government had every overridden the Lords in that way.

Waddington was relieved of his duties after the 1992 general election, compensated with appointment as governor of Bermuda where he spent the following five years. He was replaced as leader of the Lords and pseudo-Willie by John Wakeham, lately energy secretary but before that leader of the Commons and chief whip. He was a skilled manager of parliamentary business with an instinctive understanding of how to get compromises agreed, and relished the horse-trading and arm-twisting of Westminster’s back rooms. One journalist described him as “a kind of prêt-à-porter version of Whitelaw”, while Major himself later said he was “subtle, reflective, a fixer, fascinated by why something happened rather than simply what had happened”. For all that, while he performed better than Waddington, he was never at home leading the Lords. He found the hereditary peers more difficult to manipulate than backbench MPs, and could not appeal to the same sense of common enterprise, of standing together or hanging separately. He agreed with Major he would do the job for two years, and duly retired in July 1994.

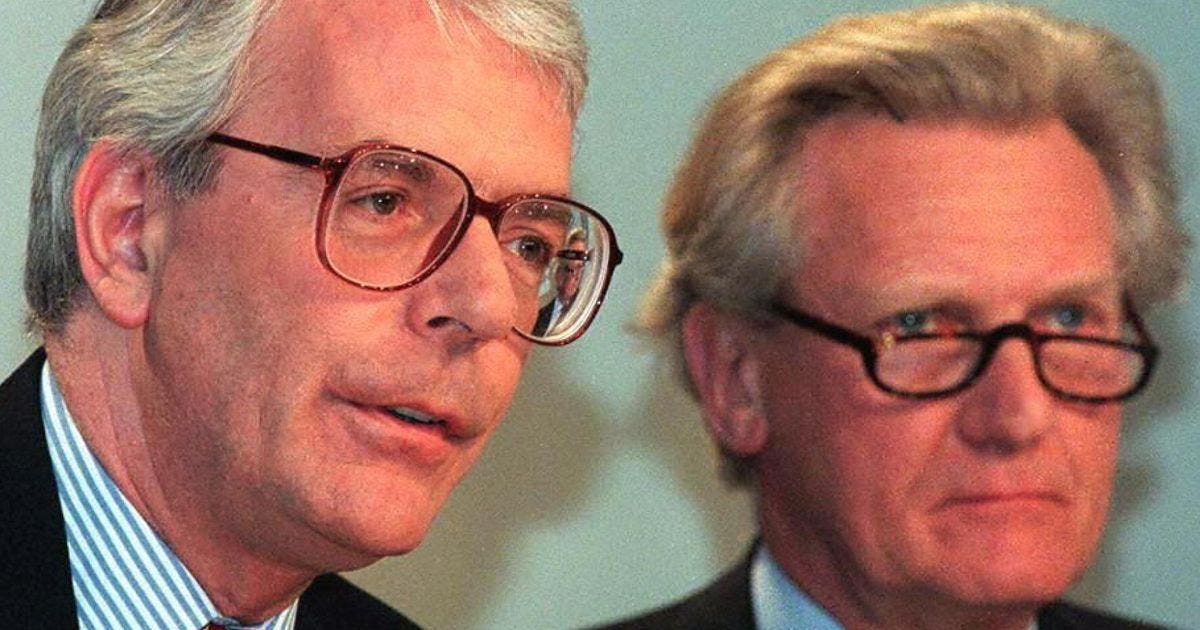

Major had one official deputy. After he resigned the party leadership to draw out his critics and was re-elected in July 1995, he approached his cabinet’s biggest beast, Michael Heseltine, offering him a powerful remit as first secretary of state (a title dormant since Barbara Castle had left government in June 1970) and an influential role within the Whitehall machinery. It was a generous offer, born of genuine need for support and help, but it asked a lot of Heseltine too. In effect, he was being asked to give up any remaining ambition to lead the party; he was 62 to Major’s 52, and defeat at the forthcoming election seemed the likely outcome. But his hopes in that direction were thinning in any event. In 1993, on holiday in Venice, he had suffered a serious heart attack which had kept him away from his ministerial desk for four months, and it made him an outside candidate for the highest office if the opportunity every arose.

Heseltine was never loved by his colleagues, but he was a trouper, and couldn’t resist the whiff of cordite. In 1995, he appeared in colour while his colleagues, even Kenneth Clarke, still struggled on in black-and-white, and his speech at the annual party conference was a highlight of the week. He had first been made a minister as far back as 1970—parliamentary secretary for transport in Edward Heath’s government—and was the only member of the cabinet with a sense of grandeur, ambition and the expanse of politics. After a two-hour meeting with Major on the morning of the leadership election, Heseltine was given not just the titles of first secretary and deputy prime minister, but the chairmanship of four cabinet committees: environment, local government, economics, domestic policy and competitiveness, and the coordination and presentation of government policy (EDCP), which last met every weekday at 8.30 am. He also had a pass to allow him free access to Downing Street and the right to attend any other committee he chose.

He was therefore absolutely central to the operation of government, and revelled in it. Heseltine had always been a doer, interested in achieving policy efficiently and effectively, and Major had allowed him virtually to create his own portfolio. His own view of his role was clear.

When accepting the job I took a very simple view, I am here to act on the Prime Minister’s behalf and there will not be a glimmer of light between us, and there never was. That was the basis of my authority.

In that sense, he was echoing Whitelaw’s position 15 years before, providing loyalty and support to the prime minister to make his position more effective and more secure. But Heseltine, a successful businessman before he arrived in the House of Commons, had an interest in systems which Whitelaw had lacked. In the Thatcher years, he had tried to introduce an information management system into Whitehall to make government departments more efficient. Later he reflected:

We all knew exactly what officials were doing and what their objectives were. Now, it was a very boring thing to do. Management systems are boring and one can well understand that, but whenever I left a department, quite soon the systems disappeared. The Government said they liked it in No stone unturned, but it is never going to happen.

The creation of Heseltine’s post and the duties it carried was also a genuine and heartfelt attempt by John Major to address the perennial problem of a “hole at the centre” of government. This was an issue which many had identified but none had solved. Lord Hunt, the robustly effective and transactional Roman Catholic cabinet secretary from 1973 to 1979, had said as early as 1983, “There is in short ‘a hole in the centre of government’ and a purposeful strategy is needed to fill it.” The idea of a prime minister’s department (something for a future essay) has been raised at regular intervals since the 1960s, but has never found any formal expression.

The reorganisation of 1995 was John Major’s best attempt, in difficult circumstances when there were more urgent challenges, to construct some kind of framework for developing and driving forward government strategy and policy. He was fortunate in that his greatest potential rival, to whom he was turning, had firstly all but abandoned hopes of the premiership, and second was keenly interested in how government worked. The patchwork of responsibilities he was given reflected in part an attempt to coordinate the centre—especially his chairmanship of the unusual EDCP which met daily—and partly a representation of his own passions, including competitiveness and local government.

Was he effective? Some commentators have judged his time as deputy prime minister harshly. Simon Hoggart, an entertaining sketchwriter but addicted to the acerbic, said that he “consoled himself with titles” after seeing the leadership slip away for the last time. I’m not so sure. Certainly Heseltine has at least the average dose of politician’s vanity, from his legendary blond hair (Whitelaw described him unfavourably as “the sort of man who combs his hair in public”) to his revival of the title of president of the Board of Trade when he became trade and industry secretary in 1992 (he insisted on being addressed as “President”).

At the time, some thought Major had made a brilliant appointment. The South China Morning Post, of all journals, waxed lyrical in July 1995:

It is for Mr Heseltine to make of the post what he will, but his charisma will be an effective power if used correctly. Mr Heseltine will be there to smooth the Cabinet's way through the wash out from the Nolan Committee on sleaze and the report of the Scott inquiry into arms-for-Iraq. It seems likely he will chair Cabinet meetings as well as make public media appearances which the Prime Minister may not be free for. His influence and those of the so-called Heseltinies who follow him could dramatically colour the conduct of the Government.

Insiders felt his influence too. One ministerial colleague reflected some years afterwards:

He was a force of nature, and he pushed things along. I thought that it was Heseltine at his best. He used to be quite energetic in his chairmanship. He brought a lot more dynamism. He really was a pleasure to work with, and it was worthwhile stuff.

He pushed policy in a number of surprising areas. As the minister responsible for competitiveness, he had brought with him from the DTI the relevant 30-strong unit headed by Dr Bob Dobbie (who had previously run Heseltine’s Merseyside task force). Dobbie reported directly to the deputy prime minister, the only civil servant under permanent secretary rank to have such a relationship with him. His unit was part think tank and part executive department: “He [Heseltine] He sees us as a think tank, one which can take forward issues and policies and help him to disseminate the competitiveness message.” Heseltine was keen to carry out a skills audit on the UK. Sir Malcolm Thornton, chairman of the House of Commons education and employment committee, was positive: “Michael is looking at UK plc and what it needs to maintain a competitive edge.”

In truth, Heseltine’s tenure as deputy prime minister—22 months—was too short and conducted in circumstances too besieged to make much lasting difference. The Conservative government, in power for what would be 18 years, was sinking was degrees and had become accident-prone, the parliamentary party ill-disciplined and fractious. Ministers were tired and jaded, already thinking beyond the election of 1997 to a quieter period of opposition. Heseltine himself was upbeat in public, trumpeting the success of the economy and the growth of employment. But the result was inevitable. Had the Conservatives somehow won another term, perhaps Heseltine’s position would have borne more fruit, not only making government strategy more coherent and coordinated but giving the centre of the administration greater ability to chase up pet projects and important issues. His gifts were in some ways ideal, and his determination was second to none. But, as Jim Callaghan remarked mournfully in 1978, “There are times, perhaps every 30 years, when there is a sea change in politics. I suspect that there is now such a sea change.”

The New Labour government which took office on 2 May 1997 would feature another big beast as its deputy prime minister, and Tony Blair inevitably gave the job to his deputy party leader. From the increasingly grand and old-school Michael Heseltine, with his publishing empire and Northamptonshire arboretum, the office would go to a restless, pugnacious trade union official who had once been a Cunard steward serving drinks to Anthony Eden, John Leslie Prescott. Everything would be different.