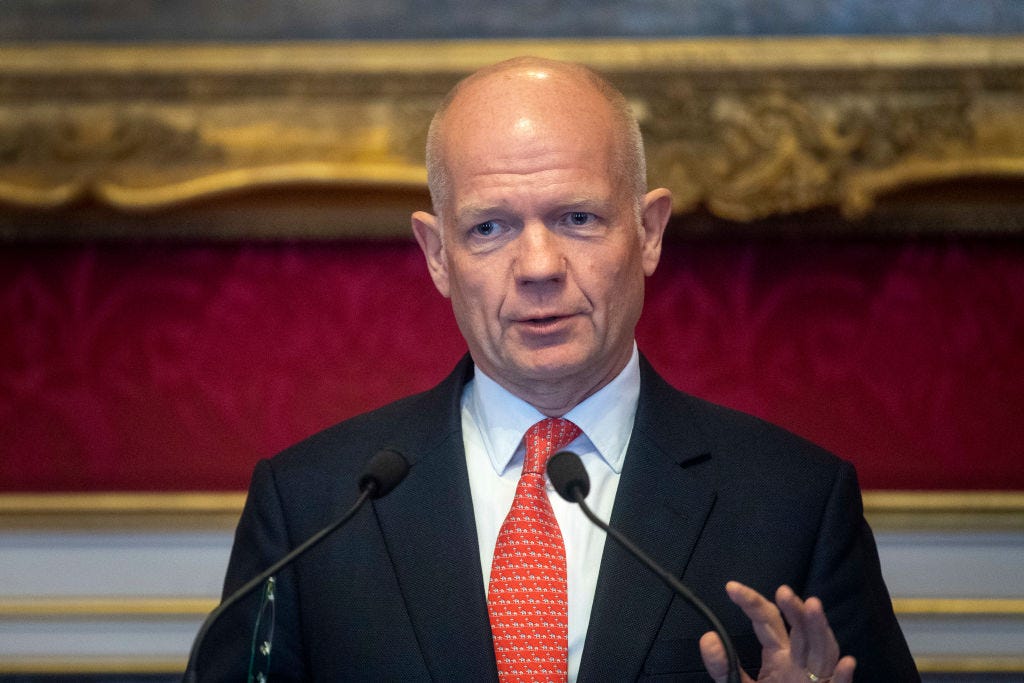

William Hague becomes Chancellor of Oxford

The former Conservative leader beat Elish Angiolini, Jan Royall and Peter Mandelson to become the university's ceremonial head and ambassador to the world

After a contest which has felt almost as long as that to be Leader of the Conservative Party, Oxford announced on Wednesday that the former Foreign Secretary and Leader of the Opposition, Lord Hague of Richmond, had been elected as the 160th Chancellor of the University. He studied philosophy, politics and economics at Magdalen College, graduating with a first-class degree in 1982, and is the eighth ex-Foreign Secretary to be Chancellor of Oxford, in many respects an impeccably traditional and establishment occupant of the office which dates back to 1224.

In the past, voting for a new chancellor has taken place in person in the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, and those casting their ballots were required to wear academic dress. This time, however, it was decided that the election would take place online. The electorate comprises all members of Convocation, which entitles anyone admitted to a degree at the university, as well as members of Congregation and retired members of staff who were members of Congregation on their retirement date, to cast a vote. Because the previous requirement of being nominated by 50 members of Convocation was removed, there were an absurd 38 candidates for the role, most of them utterly speculative. Many of their statements for the election were amusing if you have the time to read them. In reality, the plausible contenders probably narrowed down to perhaps eight:

Lady Elish Angiolini, Principal of St Hugh’s College and Pro-Vice-Chancellor

Major General Alastair Bruce of Crionaich, former Governor of Edinburgh Castle

Margaret Casely-Hayford, barrister and former Chancellor of Coventry University

Dominic Grieve, former Attorney General for England and Wales

Lord Hague of Richmond, former Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary

Lord Mandelson, former President of the Board of Trade

Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, Principal of Somerville College

Lord Willetts, former Minister of State for Universities and Science

The office of Chancellor of the University of Oxford

The Chancellor of the University performs an almost wholly honorary function at Oxford. He presides at Encaenia, the yearly ceremony to celebrate benefactors and award honorary degrees, chairs the Committee for the Nomination of the Vice-Chancellor and is Visitor, or external overseer and adviser, of five colleges: Hertford, Lady Margaret Hall, Mansfield, Pembroke, St Edmund Hall and Somerville. In the main, the Chancellor is the figurehead and leading ambassador of the university, but that is no small consideration: he plays an important role in fundraising and, up to a point, can act as the spokesman for the institution on matters of public debate. There is also a valuable role in providing informal advice to the Vice-Chancellor and the senior administration.

Traditionally, the Chancellor has been a senior figure, sometimes still active, in the nation’s political life. Oliver Cromwell, a Cambridge graduate and MP for Huntingdon then Cambridge, combined the chancellorship with his main role first as Captain General and Commander-in-Chief of the Forces and then as Lord Protector, and was replaced by his son Richard Cromwell who shortly afterwards became Lord Protector. In 1772, Lord North, then Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer, became Oxford’s ceremonial head, and his successor, the Duke of Portland, was still in post when he became Home Secretary in 1794 and Prime Minister in 1807. The 15th Earl of Derby was Prime Minister three times while serving as Chancellor, as was the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury. Lord Curzon (later Earl then Marquess Curzon of Kedleston) was elected in 1907 and went on to be Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Lords, and could easily have become Prime Minister in 1923. Lord Irwin, who became Chancellor in 1933 and succeeded as 3rd Viscount Halifax the following year), was the incumbent President of the Board of Education and went on to be War Secretary, Foreign Secretary and Ambassador to the United States, and, like Curzon, came very close to the premiership in 1940.

An unexpected contest in 1960: enter Macmillan

Halifax died in October 1959, after nearly 30 years as Chancellor of Oxford. The preferred candidate of the university hierarchy, rallied by the Warden of Wadham College, Sir Maurice Bowra, was Sir Oliver Franks. He was a former Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Supply, Provost of The Queen’s College and British Ambassador to the United States, by then serving as Chairman of Lloyds Bank. A brilliant moral philosopher and a first-rate administrator, Franks was a Liberal who supported Clement Attlee but was respected across the political spectrum, a wholly suitable and respectable candidate for Chancellor, and, aged 55, vigorous but hardly callow. However, the Regius Professor of Modern History, Hugh Trevor-Roper, an acerbic Conservative who rarely backed away from a quarrel, proposed as an alternative candidate the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan.

“Supermac” had won an exhibition to Balliol College in 1912 to read Literae humaniores but his studies had been interrupted when he volunteered for the Army at the outbreak of the First World War. Severely wounded and left permanently disabled while serving with the Grenadier Guards on the Somme in 1916, he had decided not to return to Oxford after the war, calling it “a city of ghosts” and joking that he had been “sent down by the Kaiser”. But, despite the fact he had never graduated, the university had a powerful hold on his affections. Several colleagues advised against accepting the nomination, on the grounds that he was Prime Minister and had everything to lose from a potential embarrassing defeat and nothing to gain. Trevor-Roper ran a brilliant and energetic campaign, writing to graduates to encourage them to travel to Oxford to vote on 3 March 1960, there was a surge in graduates paying the fee to upgrade their BA degrees to MAs (at that time only Masters of Arts were members of Convocation) and Conservative ministers and MPs made the journey to Oxford en masse. Macmillan was elected ahead of Franks by 1,976 to 1,697 votes, and would be Chancellor for 26 years.

Muted partisanship and a splitting of the vote

Since then the chancellorship has not been sought by politicians still in the heat of front-line combat. There has been an element of proxy war, however, and of partisan spirit. Macmillan, by then Earl of Stockton, died in December 1986 at the age of 92. He had been Chancellor for so long—he and Halifax were the longest serving of the 20th century—that the interest in the vacancy was intense. The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was mooted but her standing in higher education circles was not high, while other Conservatives tipped as possibilities included the former premiers Lord Home of the Hirsel and Edward Heath, Lord Chancellor Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone and the former Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington.

Since the only non-Conservative Chancellor in 200 years had been Viscount Grey of Fallodon (1928-33), there was a centre-left eagerness to seize the position. Former prime ministers Lord Wilson of Rievaulx and James Callaghan were suggested, as were Shirley Williams and Roy Jenkins, both former Labour cabinet ministers who had been among the founders of the SDP. Significantly, the university decided not to promote a preferred candidate, and by the time the election was held on 14 March 1987, there were four contenders:

Lord Blake, 70, Provost of The Queen’s College and historian of the Conservative Party

Edward Heath, 70, MP for Old Bexley and Sidcup and former Prime Minister

Roy Jenkins, 66, MP for Glasgow Hillhead and former President of the European Commission, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary

Mark Payne, 34, a general practitioner from Birmingham

It was not quite a left/right contest: Blake was a natural Conservative and commanded a great deal of support among academics, but the party had put its weight behind Heath’s candidacy. Payne was an unknown outsider. The split between Blake and Heath was probably decisive: Jenkins was elected with 3,249 votes, ahead of Blake on 2,674, Heath on 2,348 and Payne with 38. It seems likely that a single candidate broadly from the Conservative Party (though probably not Thatcher herself) would have carried the day against Jenkins.

Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, as he became shortly afterwards, was Chancellor for nearly 16 years. From 1988 to 1997 he also served as Leader of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords, but he had reached his true calling as a full-time grandee, publishing his memoirs, A Life at the Centre, in 1991, chairing the Independent Commission on the Voting System in 1997-98 and writing acclaimed biographies of William Gladstone and Winston Churchill. When he died in 2003, he had begun work on a life of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The most recent contest: a battle of agreeable centrists

For the election to choose Jenkins’s successor in March 2003, the university relaxed the rule that voters had to wear academic dress and, partly because of the result of the previous election in which Blake and Heath had split the Conservative vote, replaced first-past-the-post with the alternative vote system in which candidates are ranked in order of preference. However, the nominations did not create the circumstances for a simple partisan race. They were:

Lord Bingham of Cornhill, 69, Senior Lord of Appeal in Ordinary and former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

Lord Neill of Bladen, 76, former Chairman of the Committee on Standards in Public Life, Warden of All Souls College and Vice-Chancellor

Chris Patten, 58, European Commissioner for External Relations and former Governor of Hong Kong and Chairman of the Conservative Party

Sandi Toksvig, 44, comedian, writer and broadcaster

Toksvig, a Cambridge graduate, entered the race primarily as an opponent of the government’s plans to increase tuition fees and won the endorsement of Oxford University Students’ Union, although undergraduates could not vote. Bingham (Balliol, History) and Neill (Magdalen, Jurisprudence) were both weighty and impartial figures, but the bookmakers’ favourite was Patten (Balliol, Modern History), still enjoying a high profile after his tenure as the last Governor of Hong Kong and Chairman of the Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland.

It was an accurate prediction. Toksvig was eliminated in the first round of voting, although she polled only around 100 votes short of Neill’s tally, and in the second round, Patten was comfortably victorious with 4,203 votes, ahead of Bingham on 2,483 and Neill on 1,470. It had been, in many ways, a contest of the “reasonable centre”. Patten was by that time semi-detached from the Conservative Party of Iain Duncan Smith, and emerged as a potential compromise candidate (proposed by Silvio Berlusconi!) to replace Roman Prodi as President of the European Commission in 2004, as the UK, Spain, Italy and Poland fought the Franco-German candidacy of Guy Verhofstadt; Portugal’s José Manuel Barroso was eventually appointed. He refused to oppose tuition fees “root and branch” on the grounds that they were a necessary component of the university’s financial existence.

Bingham had declared his support for top-up fees but his judicial reputation was impeccable: Lord Hope of Craighead, later Deputy President of the Supreme Court, would later call him “the greatest jurist of our time”, and Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, his successor as Senior Lord of Appeal, described him as “head and shoulders above everybody else in the Law… the great lawyer of his generation”. Neill, by contrast, was opposed to the increase in fees but did not want that issue to be the basis of his candidacy, and his independence and high-mindedness were evinced by his time heading the Committee on Standards in Public Life and his status as a crossbench peer in the House of Lords. He also had strong academic credentials as a former Vice-Chancellor of Oxford (1985-89) and Warden of All Souls College for nearly 20 years (1977-95).

It was in many ways emblematic of the Blair years. With the Conservative Party grievously wounded by two titanic general election defeats and exploring the outer fringes of electoral irrelevance, New Labour’s big-tent, non-ideological approach to politics was perhaps summed up by a contest involving a disenchanted One Nation Conservative grandee, a senior judge, a barrister with a history of academic and public service and a celebrity single-issue campaigner. Who else might have been proposed? Blair himself, the incumbent Prime Minister, was a graduate (St John’s College, Jurisprudence) but the invasion of Iraq would take place within days of the election of the Chancellor and his popularity had plummeted; he was in any event far too shrewd to risk humiliation in a needless competition.

Among Oxford-educated Labour politicians (the Chancellor need not have matriculated at the university but every occupant since the Duke of Wellington has done so), there were few obvious candidates: perhaps Lord Richard (Pembroke, Jurisprudence), the former Leader of the House of Lords; Sir Gerald Kaufman (Queen’s, PPE), Chairman of the House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee, had never had widespread popularity despite great ability; Lord Radice (Magdalen, History), a pioneering Labour moderniser, was a considerable intellect but relatively unknown; Lord Healey (Balliol, Literae humaniores), the former Chancellor of the Exchequer, was far too old at 85, as was former Labour leader Michael Foot (Wadham, PPE) at 89, though both were brilliant minds.

Elsewhere, Baroness Williams of Crosby (Somerville, PPE), as Shirley Williams had become, ruled herself out of contention because of her opposition to top-up tuition fees. With the Conservatives marginalised, there were few possible runners from the right beyond Patten: Lord Heseltine (Pembroke, PPE) was about to celebrate his 70th birthday; Lord Waldegrave of North Hill (Corpus Christi, Literae humaniores), had a strong academic background as a former Kennedy Scholar at Harvard and a Prize Fellow of All Souls and was at that point Chairman of the Rhodes Trust; John Redwood (Magdalen, Modern History) also had strong scholarly credentials as a former Examination Fellow of All Souls and a doctor of philosophy but suffered from public unpopularity; at that point, William Hague was only 41 and still defined by his unsuccessful tenure as Leader of the Opposition.

(Kaufman, Redwood and Hague would anyway have been ineligible under regulations passed by Council in 2002 which disqualified anyone who was “a serving member of, or a declared candidate for election to, an elected legislature”.)

Patten retires and Oxford runs a “modern” election

Since 1483, the Chancellor of the University of Oxford has been elected for life. Patten, however, announced in February this year that he intended to step down at the end of the academic year. He celebrated his 80th birthday in May, and, as he wryly noted, “I hope that there will be many more birthdays to come. But I am unlikely to have another 21 years in the job as Chancellor of the University.” Earlier this year, the Statutes of the University were amended and now the Chancellor “shall hold office for a fixed period decided by Council or until their resignation”. This period has been set at 10 years.

So a new election for Chancellor was upon the university. Almost as soon as Patten had resigned, there were rumours of potential candidates: Rory Stewart (Balliol, PPE), podcaster, author and former Conservative cabinet minister, considered the idea but decided in June not to offer himself as a candidate; former prime ministers Baroness May of Maidenhead (St Hugh’s, Geography) and Boris Johnson (Balliol, Literae humaniores) were both mentioned; Sir Tony Blair ruled himself out at an early stage. Former Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan (Keble, PPE) submitted an application in August but two months later this was rejected for unknown reasons.

As I said earlier, there were probably eight even vaguely plausible candidates, but the conventional wisdom was that it was likely to be a two-horse race between former cabinet ministers Hague and Mandelson. Both are now beyond the front-rank stage of their political careers: Hague left the cabinet and the House of Commons in 2015 and Mandelson ceased to be a cabinet minister in 2010 (though rumours persist he will be the next British Ambassador to the United States). But at 63 and 71 respectively, they both maintain active public profiles and are frequent commentators on public life. Hague is a columnist for The Times and a contributor to its podcast The Story, President of the Britain-Australia Society and Chairman of the International Advisory Board of the strategic advisory firm Hakluyt and Company. Mandelson is President, Co-Founder and Chairman of the International Advisory Board of Global Counsel, another advisory firm, serves on the Advisory Board of Ventura Capital and appeared on the Times Radio podcast How to win an election. Both are members of the House of Lords, although Hague is currently on leave of absence.

Angiolini and Royall were both slightly unusual candidates in being serving heads of house, Angiolini as Principal of St Hugh’s College since 2012 and Royall as Principal of Somerville College since 2017.

The former is a lawyer and public prosecutor by background, joining the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service after qualifying and serving in the Scottish Government as Solicitor General for Scotland (2001-06) then Lord Advocate (2006-11). The latter post had traditionally been a partly political one, changing with incoming governments, but in 2007 Alex Salmond, on becoming First Minister, asked Angiolini to stay in post but decided that the Lord Advocate would no longer attend cabinet as a matter of course. Courted by the United Nations as a potential prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, she moved to Oxford instead; since her appointment she has also undertaken reviews into the investigation and prosecution of rape in London, deaths and serious incidents in police custody, the handling of police complaints and the 2021 murder of Sarah Everard.

Royall had been a minister under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, latterly as Chief Whip in the House of Lords (2008) and Leader of the House of Lords (2008-10), and stayed on as Leader of the Opposition in the upper house under Ed Miliband. She also served on Shami Chakrabarti’s inquiry into antisemitism in the Labour Party in 2016.

Both Angiolini and Royall attracted attention for their outsider status. Neither is an Oxford graduate, and it was often noted that there had never been a female Chancellor of Oxford. (The first women to graduate only received their degrees in 1920.) Although they lacked the profiles, especially internationally, of Hague and Mandelson, it was entirely possible that they might appeal to the wider electorate which online voting had created.

In the end, 24,908 chose from a final list of five candidates. Hague’s victory was not an enormous surprise, nor was the fact that Dominic Grieve came last. It was extraordinary, however, that in the first stage of voting Mandelson was a poor fourth with 2,940 votes, less than 500 ahead of Grieve. Royall was a muted third on 3,599 and Angiolini a respectable second with 6,296. Hague’s initially tally of 9,589 seemed decisive, although by the fourth and final stage, with all the preferential votes distributed, it was not a landslide: Hague won 12,609 votes and Angiolini accumulated enough second preferences to reach 11,006. It is a result few would have predicted in full during the campaign, and Angiolini’s achievement is impressive.

Should non-Oxford graduates care?

Does all of this matter? The Chancellor of Oxford has, after all, very few executive powers, and Hague has hardly broken the mould: Jenkins and Grey, with 21 years between them, remain the only non-Conservative chancellors in more than two centuries, and Hague is the sixth former Foreign Secretary (and third Conservative leader) among the 10 most recent chancellors. While he is a Conservative, the election was never framed in explicitly party political terms, nor even definitively in the context of left v. right. Certainly Hague’s victory has little to say, good or bad, for the current leadership of the Conservative Party. It is also, let us remember, a process which involved a very small number of people—25,000, less than half the capacity of the Emirates Stadium, for example—all of them (by definition) Oxford graduates, with everything that implies.

In any event, the post of chancellor of any university in the UK is largely ceremonial one. (The title is sometimes used differently in the United States.) In general it remains the preserve of the great and the good, though with a more significant “celebrity” contingent than was once the case: HRH The Princess Royal (London, Edinburgh, Highlands and Islands), Lord Sainsbury of Turville (Cambridge), HRH The Duke of Edinburgh (Bath), Hillary Clinton (Queen’s Belfast), Baroness Lane-Fox of Soho (Open), Sir Grayson Perry (University of the Arts London), Ruby Wax (Southampton). In terms of the day-to-day administration and even the strategic planning for higher education, that responsibility lies with vice-chancellors and their senior management teams.

On the other hand, Oxford (or rather Oxbridge) is not like any other university. Oxford and Cambridge are among the most famous institutions of higher education in the world, and almost the oldest in continuous operation, with only the University of Bologna having a claim to greater antiquity. The Times Higher Education world ranking of universities for 2025 put Oxford at number one, and has done so every year since 2016/17. That gives the university a significant cultural and policy influence. Some of this is inevitably channelled through the Chancellor who, in the university’s description, “undertakes advocacy, advisory and fundraising work, acting as an ambassador for the University at a range of local, national and international events”.

Lord Hague of Richmond has for the next 10 years a powerful platform but also a substantial responsibility. He will have to wrestle with a number of issues, including the university’s finances: that means not only fundraising and philanthropic donations but also a more fundamental consideration of how British universities are funded. It is widely agreed that higher education is facing a funding crisis which could be an existential threat to some universities, and in October a report by Universities UK, Opportunities, growth and partnership: A blueprint for change from the UK’s universities called the financial arrangements “unsustainable”. All British universities are private institutions, but the vast majority derive most of their income from government sources, with only five being truly independent: Arden, BPP, Buckingham, the University of Law and Regent’s University London.

Oxford is a wealthy institution, with an endowment of more than £8 billion, so it does not face a threat to its existence. It must, though, operate in the same ecosystem ad the country’s other universities. Some have suggested that the more successful institutions should “go private”, that is, move away from public funding and rely wholly on generating their own income, as do the leading American universities.

Intimately connected to dependency on state funding is the issue of access and diversity. Oxford is very conscious of the proportion of students it admits who attended fee-paying schools, which last year was just under a third: it has risen slightly every year since 2020, though over the last 25 years as a whole it has fallen significantly and was over half at the turn of the millennium. Oxford will always face a difficult challenge in this respect: in terms of perception, there will always be those who criticise the university for being “unrepresentative” of the population as a whole, and there are still cultural and societal as well as economic barriers to applying to and being accepted by Oxford. At the same time, it is unrealistic to expect an elite university—literally the best in the world—to have a student body which perfectly reflects the wider population by every demographic measure, and Oxford has to be vigilant that it does not lower standards in the pursuit of accessibility. While it remains dependent on income from the government, however, policy developed for political reasons in Whitehall will always be a factor in its decision-making.

Hague’s involvement in all of these areas, as well as other sensitive topics like free speech, academic freedom, the legacy of colonialism and its part in contemporary politics and the responsibility of universities as investors, will be informal and advisory. The Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey, who took office in January 2023, would nonetheless be wise to talk extensively to a chancellor who headed the Foreign and Commonwealth Office for four years and spent 30 years in national and global politics. William Hague has not taken on a position which will make unbearable demands on his time, but it is one which gives him the opportunity to make a contribution to some of the most challenging public debates we face. In that sense, then, this week’s election does matter.