Wake up, sheeple! The lure of conspiracy theories

In politics we are now divided not only by ideology but by an inability to agree on facts themselves, and conspiracy theories are entrenching themselves

An old friend from university believes that everyone should believe one conspiracy theory, not so much for its veracity as for the intellectual exercise of challenging received wisdom and experiencing going against the flow. It teaches you to think critically, the return to first principles and to scrape away the accretion of lazy acceptance by generations or centuries. The problem is that those who really immerse themselves into a conspiracy theory rarely stop at one: the thrill of secret knowledge, of belonging to select group of believers and a mindset of scepticism tends to drive people to believe more and more ideas which are prima facie preposterous but in some eyes reveal a much more satisfactory narrative of the world around us than the so-called “established facts”.

We are in some ways a sophisticated audience now, and I suspect a lot of us at least half-believe what would commonly be classified as a ‘conspiracy theory’. If nothing else, we will have have serious doubts about the traditional narrative of an event or series of events, doubts powerful enough to make us conclude the narrative is wrong, even if we do not have a replacement to insert in the historical record. I certainly fall into that category: I am quite satisfied, for example, that Lee Harvey Oswald was not the only gunman in Deeley Plaza on 22 November 1963, that he did not fire all the fatal bullets and that he was not a lone wolf, solely responsible for the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

This doesn’t mean I have a full alternative story to explain all the many discrepancies in the historical record. I recently rewatched Oliver Stone’s bloated and freewheeling 1991 film JFK, and anyone who has seen it (it is very much worth watching) will know that there are some superb performances as well as some far-fetched but earnestly presented links of logic which are barely able to bear the slightest strain. I watched it with a friend who had never seen it before (it is before her time) and, while her attention was elsewhere, she occasionally looked up, furrowed her brow and asked “What the fuck is going on?” I suppose if you aren’t prepared for Stone at his most hectoring, then Joe Pesci’s eyebrows, Tommy Lee Jones’s bleached crewcut and Kevin Costner’s gumbo-like good-ol’-boy drawl are a lot to take in, let alone some of the more preachy deep-state theories and Donald Sutherland’s outstanding cameo as Mr X, featuring cinema’s least logical method of counting on fingers.

I have a few other vaguely non-standard beliefs, as it happens: I strongly suspect the Stone of Destiny is a fake, a random chunk of sandstone palmed off on Edward I by the Augustinian canons at Scone Abbey rather than the genuine article on which kings of Scots had traditionally been crowned. Why would they give him the real thing? The English king presumably had no idea what the Stone of Scone looked like and would have been satisfied with any geological feature. But this is not a theory particular to me, nor do I pretend to know what might have happened to the real stone.

There is also a strange no-man’s-land of conspiracy theories, or challenges to traditional narratives, in the form of ideas which we now know to be probably true but have not yet fully displaced the legend from the popular consciousness. For example, we have known since 1960 that Viking explorers, probably from Iceland, reached and settled in North America beginning in the late 10th century. Yet our common cultural awareness still tends to hail Christopher Columbus (who was not, remember, looking for a new continent at all, but a shorter route to India) as the first European to land in the Americas. Nevertheless, knowing about the Norse settlements at Vinland is not a conspiracy theory.

More prosaically, we are familiar with the notion that the first US president, George Washington, had wooden false teeth. It even makes it into the lyrics of the magnificently weird Boston Tea Party (1976) by the Sensational Alex Harvey Band (“And the president spits out the news/He’s biting on wooden teeth”). But it is not a daring refutation of conventional wisdom to be aware that the president’s dentures were in fact elaborate constructions made of brass, gold, ivory and, unpleasantly, teeth recovered from slaves. The myth of wooden teeth may have stemmed from the fact that the ivory easily became discoloured: Washington was once advised by his dentist that they became “very black... Port wine being sower takes of[f] all the polish”.

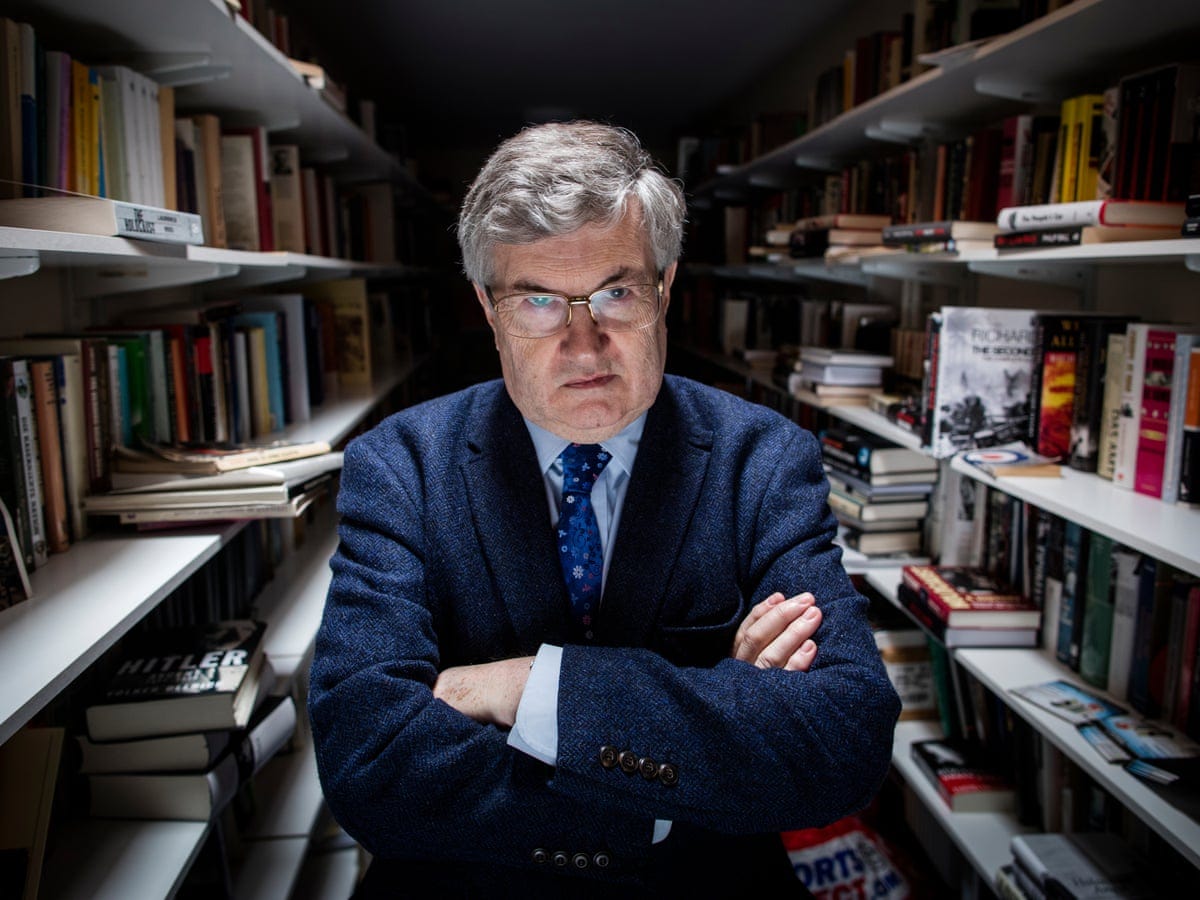

Why are we so attracted to conspiracy theories? There are better qualified people than I to explain the phenomenon fully: in particular, I would direct to you an episode of the excellent podcast Behind the Spine presented by my friend Mark Heywood, in which he interviews Professor Sir Richard Evans of Wolfson College, Cambridge, to explore why we have an urge to reject what seem like straightforward facts in pursuit of more elaborate (and usually more sinister) explanations.

I think there are (at least) three main explanations. The first is a very ancient urge, the desire to make sense of the world around us and to impose an order on what can often seem chaotic. This is one of the impulses which drove the development of the most primitive religions. We don’t know when “religion” in any meaningful sense began: it may have been as long ago as 300,000 years in the past, when there were apparently deliberate, ordered burials of early homo sapiens and Neanderthals which may indicate some sort of beliefs which were translated into rites. The oldest likely religious site is the Neolithic site at Göbekli Tepe in south-eastern Turkey, dating from between 9,500 BC and 8,000 BC and beloved of archaeological conspiracy theorists like Graham Hancock. But we see common strands of thought in religion: they tend as a first step to attribute agency to natural phenomena like weather and geographical features. So the Greeks believed that thunder was the particular domain of Zeus, the king of the gods, and his Roman counterpart Jupiter, while Germanic and Norse mythology had Thor (who possessed at least 15 other names), the Celts worshipped Taranis, the Slavs believed thunder was under the control of Perun, and so on.

Ancient humans did this, of course, to give a meteorological event which could be dangerous and must often have been terrifying a personality, a recognisable figure who could then be worshipped and placated. Doing that gave them a sense of control over the weather, albeit an illusory one. We are never as afraid of something we can name as that which is unknown. I suspect conspiracy theories can act in the same way: disorder unsettles us, and events which are random are therefore unpredictable. As a result we can do nothing to prepare for them or guard against them. By contrast, if we can fit events into a framework, even one we create ourselves, they become more manageable, and we reduce them in scale and the measure to which they frighten us. Ordo ab chao, one of the most primitive human instincts: a conspiracy theory weaves connections between apparently disparate elements and gives us the impression of having ordered the universe.

The second factor is a desire to be privy to secret knowledge. To the right personality, embracing a conspiracy theory gives the believer a deeper, more profound and more sophisticated knowledge and therefore a perceived advantage and superiority. If we have connected events in a way which is not part of the accepted narrative, we have seen behind the façade of public knowledge and joined an intellectual elite. Not only that, but, in a more basic way, we have refused to be fooled, we have resisted falsehood and evaded the trickery of those who try to deceive us. It therefore gives us agency and control over our surroundings as we do not bow to the control imposed by The Big Lie.

The third factor is more recent in its genesis, I think, and it manifests itself in a fundamental distrust of institutions, politicians and “authority” in general. It is summed up, regrettably, by the paraphrase of Michael Gove as saying during the 2016 Brexit referendum campaign “We have had enough of experts”. It seems simple enough: an anguished, frustrated, populist howl of rage at at a hierarchy with which the people had lost patience. Now, as it happens, that is not at all what Gove meant. What he actually said was this:

I think the people in this country have had enough of experts from organisations with acronyms saying that they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong.

He was clearly referring to specific institutions which had made forecasts which proved not to be accurate; but history has already forgotten his meaning as the paraphrase is more convenient. It may rankle Gove, though he is in many ways an equable man, but his awkward paraphrase encapsulates (but in no way caused) an undoubted revolt against informed opinion and authority. We do not like, in short, being told what to think, even if that is being told what is true. And this rejection of authority opens the door wide to acceptance of conspiracy theories, because their very existence by definition finds fault with, and dishonesty inherent in, authority.

In one sense, of course, conspiracy theories are an amusing diversion for the eccentric and credulous on the journey of life. I recently watched a documentary called Behind the Curve, a 2018 film which explored the flat Earth movement and in particular two leading exponents of this theory, Mark Sargent and Patricia Steere. They were rather a charming, ingenuous pair (not, it seems, a couple but bound by obvious affection), and struck me as largely harmless, though their attachment to the idea of a flat Earth was as dogged as it was crackpot. And it is hard to see anything malign in the conferences the documentary showed, largely enthusiastic but awkward people, internet devotees all, showing genuine glee at being among people who shared their odd world view.

At one point—I don’t think I imagined this, though I know it to be true from subsequent reading—the charming fact was dropped that Mark, the hero of the film, also believes in Bigfoot. Of course he does; as I noted at the beginning, it is a rara avis who subscribes to one conspiracy theory and one only. And Bigfoot is in a way like a flat Earth: it is vastly unlikely to be true, and believing in it doesn’t seem to do any harm. Except in a way it does, because what these beliefs do is chip away at rationality, at science and at respect for those who have learning and expertise. Behind the Curve featured a psychiatrist who explained the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias by which those who have little knowledge or expertise in a subject substantially overestimate their ability. Its application to conspiracy theories is obvious: you can learn one or two facts on the internet, which seem to challenge in some way the conventional wisdom (though are often reconcilable in the end), and use the possession of these facts to put yourself on a level with a subject specialist who has been studying the field all his or her career. It is the embodiment of Alexander Pope’s phrase that “A little learning is a dangerous thing”. After all, as he goes on, “shallow draughts intoxicate the brain/And drinking largely sobers us again”.

This is where conspiracy theories meet real life. One of the most pernicious conspiracies recently, or perhaps groups of conspiracies, has been the welter of dunderheadedness surrounding the Covid-19 virus. While the true story of the pandemic may yet to be written, and may not even emerge (in the UK) after the official public inquiry which is being chaired by Baroness Hallett KC, a former appeal court judge who also acted as coroner for the deaths of those killed in the 7 July 2005 terrorist attacks, there is a great deal of misinformation, disinformation and plain falsehoods in the air. Those who exhibit the three qualities I have identified—a desire to impose order on the world, an enthusiasm for secret learning and distrust of established authority—are extremely susceptible to simple, or interconnected, explanations of the origins and spread of the pandemic.

The conspiracy theories cover a great deal of ground, from harmless misapprehension to a menace of a lie. One notion, that Covid-19 is no more serious than normal influenza (in fact the fatality rate may be between five and 10 times higher), does not really harm except in creating false expectations in the minds of the public that it is not a serious infection. By contrast, fears about the safety or efficacy of vaccines, up to and including the belief that Bill Gates is using the vaccine to implant microchips in those who receive it, can seriously affect the rates of vaccine hesitancy; and there is a cumulative effect, as a greater number of unvaccinated people can allow the virus to spread more widely, making the pandemic worse.

This is, of course, a development of pre-existing theories about vaccines. I’m afraid I have very little patience with anti-vaxxers. We know, for example, the baleful effect that a paper in The Lancet in February 1998 by Andrew Wakefield and others about links between the MMR vaccine and autism had. It suggested that eight of 12 children studied had some developmental challenges which were linked to the MMR vaccine; the links were fake, and Wakefield was struck off the medical register. The scientific consensus is that there is no link between the MMR vaccine and autism, while the vaccine, if administered properly, protects 97 per cent of children against measles, 88 per cent against mumps and 97 per cent against rubella. Before widespread immunisation, measles killed 2.6 million people a year. That has been brought down by over three-quarters. But the damage done by Wakefield is lasting, and anti-vaccination activists use the vestigial fears of harming children—and how potent that fear is!—to deter parents from having the vaccine. I take a relatively hard line on this (though I will note that I don’t have children): the risk is overwhelmingly on the side of not having the vaccine, the diseases against which protects can kill, and if you refuse to have your child vaccinated because of misinformation (or what we laymen call “bullshit”), you are a fool and a bad parent.

The apotheosis of conspiracy theorising is Donald Trump. He had peddled the most insidious of conspiracy theories—that he in fact won the 2020 presidential election but it was “stolen” by the Democrats—and at very least failed to react properly to an attempted coup d’état on 6 January 2021. That is frightening enough, especially when one learns that between 60 and 70 per cent of Republicans still openly affirm that the election was invalid and that Joe Biden’s presidency is illegitimate. The damage Trump and his acolytes have done to US political institutions and culture is incalculable, and it still hangs in the balance whether it can ever be repaired. But Trump’s chilling effect goes wider than this: he has poisoned the well of American political discourse. He has hacked away at the very notion of truth, from his embrace of the theory that Barack Obama was born not in Hawai’i but in Kenya, and therefore ineligible to stand for the presidency, to the notion that wind turbines cause cancer. There seems to be no outlandish theory he will not entertain in his role as a disruptive agent; Wikipedia has a whole page dedicated to the conspiracies he has endorsed or supported.

This mixture of crude, opportunist politics with literally no regard for the concept of truth and a susceptibility of plentiful available conspiracy theories poses a huge threat to our political discourse. In the United Kingdom, I do not think it is yet existential; I reserve judgement on the US. But it is a very dangerous venom leaching into the way we do politics. Only yesterday, Andrew Bridgen, the maverick Conservative MP for North West Leicestershire, announced on Twitter that he had visited the US at Christmas and received information that the Covid-19 virus had been engineered by the Department of Defense. This is, it goes without saying, an outlandish and absurd accusation, and Bridgen has always been on the fringes of his party. But remember: this is an elected UK parliamentarian saying that the Covid-19 pandemic, which killed perhaps as many as seven million people worldwide, originated in the Pentagon. That is quite a theory.

I wish I could offer some potential solutions to the situation in which we find ourselves. Perhaps it will simply ebb away just as it has flowed in, a natural tide in the affairs of politics, and all will be well. However, I suspect it is more likely that our politicians, from all parties, will have to work hard to gain every inch of ground in terms of trust from the electorate. It is not a party political issue but an institutional one, and I hope, even as partisan spirit sharpens as we move towards a general election next year, our leaders can cooperate and coordinate to rebuild the relationship of trust with the people which is the sine qua non of everyday politics.