The US presidential race: observations

It is four weeks since President Joe Biden and Donald Trump walked onstage in Atlanta for the first presidential debate: a lot has happened since then

It is almost incredible to think that it is only four weeks since the first head-to-head presidential debate of the 2024 campaign, organised by CNN, took place in Atlanta. We were all curious to see how President Joe Biden, 81 years old and seeming to have aged rapidly in recent months and years, would hold up against the incoherent, disjointed energy of his Republican challenger, Donald Trump, who had turned 78 a fortnight before. Few can have seen how much the ensuing month would hold.

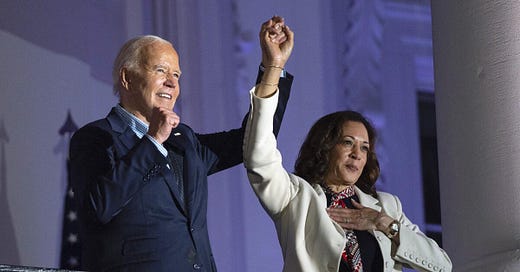

Biden performed catastrophically, of course, and suddenly his cognitive abilities were the main story of the election. Gradually senior Democrats, at first privately then publicly, intimated that perhaps the president was no longer the right man to ask for another four-year term in the White House, though Biden himself seemed stubborn and determined. On 11 July, at a press conference to conclude the NATO summit in Washington, Biden managed to refer to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine as “President Putin”, and to his vice-president, Kamala Harris, as “Vice-President Trump”. Two days later, 20-year-old Thomas Crooks attempted to kill Trump at a rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, a bullet nicking the candidate’s ear (a former fire chief, Corey Comperatore, was killed while shielding his family from the gunfire).

Two days later, on the first day of the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Trump named Senator J.D. Vance of Ohio as his vice-presidential running mate. On 17 July, in impossibly bad timing, President Biden tested positive for Covid-19 and was forced to isolate at his home in Delaware. Then, on Sunday 21 July, Biden announced that he would not, after all, seek re-election as president but would allow the Democratic Party to choose a new nominee, and his then endorsed Vice-President Harris for that position.

The commentariat has struggled to keep up. I have been focusing on domestic politics, as the new Labour government finds its feet and the Conservative Party girds its loins for a leadership contest, but at this point, while there is the faintest hint of a pause, I thought I would offer a few observations. They do not add up to a comprehensive narrative, because I cannot yet see the shape of that narrative, but they are all elements in the story. Some are based solely on the evidence I can gather, and some are matters of my individual judgement deriving from more than 30 years obsessed by politics at home and abroad.

(The first presidential election to which I paid any real attention was the 1996 contest, when President Bill Clinton convincingly defeated his Republican challenger, former Kansas senator Bob Dole. At the time, Dole, a Second World war veteran with limited movement in his right arm after being hit by a German shell, seemed ancient and decrepit. He was 73.)

Biden did the right thing in stepping aside

In this particular context, I’m not interested in whether Joe Biden was the best candidate to defeat Donald Trump on 5 November. I think Biden made the right decision in stepping aside because there is substantial circumstantial and anecdotal evidence that he is suffering from some form of cognitive decline which is incompatible with being president of the United States, the most demanding job in the world. Indeed, as I wrote recently in The Hill, I think there are valid concerns over whether Biden is fit and able to discharge the office of president now and until his successor is inaugurated on 20 January 2025.

For understandable, if not necessarily forgiveable, reasons, many senior Democrats over the past couple of years have downplayed or dismissed any concerns about Biden’s mental acuity and cognition. These anxieties have been dismissed as partisan points-scoring, and Democrat after Democrat was willing to take to the airwaves to stress how focused and mentally agile the president was, mysteriously always under circumstances when no impartial observers were present.

It is worth remembering that in 2019, Biden considered making a public pledge that he would only seek a single term as president; he would be, and was, 78 years old at his inauguration, by far the oldest chief executive the nation had had. Ronald Reagan had left office at 77, in 1989, and was notably old then, while the next oldest had been Dwight Eisenhower, 70 when his second term ended in 1961. Biden was older than both before being sworn in. However, he chose instead to make it “known” to aides and allies that he was unlikely to seek re-election. Politico reported:

According to four people who regularly talk to Biden, all of whom asked for anonymity to discuss internal campaign matters, it is virtually inconceivable that he will run for reelection in 2024, when he would be the first octogenarian president.

That has been proven accurate, but only after a long, drawn-out battle. I said plainly after the debate that those around the president should be required to answer a number of questions about his cognitive condition, how quickly and how far it had declined, and when significant issues had first arisen. These questions will be shuffled to the back of the pile for the moment, but eventually they will be asked, and it is hard to avoid the conclusion that some in Biden’s inner circle have not only concealed the truth from the public but have actively lied to the electorate. It is easy to understand their motivation in doing so, but that does not make it any less the wrong thing to have done. I suspect that many Democrats became so hypnotised by the necessity of defeating Donald Trump in November that in pursuit of that goal they found themselves able to excuse any misdirection, concealment or untruth as a lesser evil.

The president of the United States is not a king. Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution has existed since 1967 to make provision for circumstances in which the president is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office”, and the American political system expends huge amounts of energy every four years in choosing not only a president but a substitute. According to the constitution, the vice-president is the presiding officer of the United States Senate, but in truth he or (since 2021) she occupies that role as part of the presidential succession. John Adams, the first vice-president (1789-1797), summed up his role when he said “In this I am nothing, but I may be everything”. At any point, therefore, Biden could have relinquished office and would have been replaced seamlessly by Vice-President Harris. If he or his advisers did not think she was capable of being president, she should not have been on the ticket in 2020.

In any event, Biden has eventually made what is very obviously the right decision. He will not seek another four-year term this November, and the Democratic Party, perhaps at its convention in Chicago on 19-22 August, will select a replacement as presidential nominee.

It is hard to see beyond Harris ’24

It has no connection to any views I may have on her when I say that I think it is overwhelmingly like that Kamala Harris, as incumbent vice-president, will be chosen as the Democratic nominee. This is not a matter of her “deserving” it because she is vice-president or claiming it as of right. There are several reasons why I think it will happen.

The first is a drearily administrative but hugely important financial reason. The legal consensus seems to be that money raised for the Biden-Harris re-election campaign can only be spent in support of the candidacies of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. Therefore there is no problem if Harris becomes the nominee, because she is still on the ticket, but if the party nominated two other people, the money could no longer be accessed. This is not small change: The New York Times reports that, as of 30 June, there was $96 million in the campaign fund. In addition, Harris received donations totalling $100 million between Sunday afternoon and Monday evening in the wake of the president’s announcement. She is clearly the candidate who will have most money available to her.

Another significant of negative factor which has been much discussed is the “optics” of the Democrats choosing someone other than Vice-President Harris. Bluntly, the argument is this: if an ethnic-minority woman who is already the incumbent vice-president is passed over, it will seem not like the selection of a different candidate but a decision that Harris, for whatever reason, should not be the nominee. There are people who will ascribe that to ingrained, perhaps institutional, racism and misogyny. Whether that would be the motivation or not, it is easy to imagine how such a course of events might be perceived by some Democrats and could be portrayed by the Republicans in the heat of an election campaign.

For many people, understandably, the key to Harris’s candidacy will be a very simple question: can she beat Donald Trump in November’s election? A Reuters/IPSOS poll conducted on Monday and Tuesday showed that Harris led Trump by 44 per cent to 42 per cent, the two having been tied on 44 per cent on 15-16 July. That advantage is of course within the margin of error but it is instructive and suggests that Harris at this stage is competitive against Trump. However, an average of polls as of 24 July, published in The New York Times, showed Trump ahead of 48 per cent and Harris on 46 per cent. The majority of polls over the past week have shown Donald Trump ahead, usually by very slender margins.

Assessments of Harris are being made which run the gamut from fawningly adoring to viciously damning. The majority of these, predictably and understandably, are fundamentally motivated by partisan political reasons, though some have been balanced and even-handed. What does seem to be the case, however, is that there is no evidence that Harris has an electoral disadvantage against Trump so great as to make the selection of a different candidate essential. All of that suggests to me that Harris will be the nominee, not least because there are no obvious good reasons for the Democrats not to choose her.

The running mate: does it really matter?

Almost as soon as the news that President Biden was stepping aside had broken, eager commentators had hopped beyond the question of whether Vice-President Harris would be the replacement nominee and on to the issue of whom she might pick as her running mate and putative vice-president. Any significant political vacancy, let alone potentially for vice-president of the United States, attracts frenzied speculation, and some contributors quickly lose their mooring in reality and move instead into wish fulfilment, but there do seem to be some reasonably well accepted facts.

According to The Financial Times, Eric Holder, attorney general from 2009 to 2015 under President Obama, is heading a process of vetting and selection for potential candidates for the vice-presidential nomination. The front runners, especially favoured by major Democratic donors, are reported to be Governor Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania, Governor Roy Cooper of North Carolina and Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona. However a slew of other names has been aired: Governor Andy Beshear of Kentucky, Governor J.B. Pritzker of Illinois, Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Governor Tim Walz of Minnesota, Pete Buttigieg, secretary of transportation, Governor Wes Moore of Maryland and secretary of commerce Gina Raimondo.

The eagle-eyed will notice that all but two of these names are men, most are state governors and all but one are white. A first principle of the choice is assumed to be that Harris, as a black woman, will “need” to select a white man as her running mate to balance the ticket, and that, by implication, there are enough American voters who will not support two women for president and vice-president as to make it an unnecessary risk. This may be true: it is striking that the first (and so far only) female presidential candidate chosen by a major party was Hillary Clinton, the Democratic nominee in 2016, while the only other women to be on a Republican or Democratic ticket were Rep. Geraldine Ferraro of New York, who was Democrat Walter Mondale’s running mate in 1984 (the pair carried only single state while President Reagan won 49, with a margin of around 17 million votes), and Governor Sarah Palin of Alaska, chosen by Senator John McCain to be the vice-presidential nominee on the Republican ticket in 2008 (they lost convincingly to Senator Barack Obama and Senator Joe Biden). So Kamala Harris is the first woman ever to be vice-president, and, if she was victorious in November, would be America’s first female president.

However, all kinds of criteria are being pored over. The president and vice-president cannot be from the same state, which would have made the candidacy of Governor Gavin Newsom of California problematic, though he quickly ruled himself out. Given that Harris came to the vice-presidency having been senator for California from 2017 to 2021 and before that attorney general of California 2011-17, the received wisdom is that a running mate should come from the East coast or from the Midwest: Shapiro is from the North East, Cooper from the South and Kelly from the South Western border. Another advantage is someone who has won the governorship either of a swing state or a state which traditionally votes Republican, thereby proving he or she can win over Republican and independent voters. Arizona, Michigan and Pennsylvania all voted Republican in 2016 but Democrat in 2020, which would burnish the claims of Kelly, Whitmer and Shapiro.

If you have the time and the inclination, and that data, you can parse Kamala Harris’s candidacy, track record, politics and personality in dozens of ways, and perform the same exercise with every potential running mate to try to find a perfect combination. This is not an innovation: the same measurements have been taken of vice-presidential candidates for decades, at least since 1960 when Senator John F. Kennedy, the young, rich, privileged, liberal Massachusetts legislator invited his party’s leader in the Senate, Lyndon Johnson, an experienced conservative senator from Texas, to be his running mate.

It happens again and again: in 1960, Vice-President Richard Nixon selected a fellow foreign policy specialist, former United Nations permanent representative Henry Cabot Lodge Jr, because that was what he wanted to use as the main thrust of his campaign; in 1968, Nixon chose Governor Spiro Agnew of Maryland because he was a liberal who had suddenly that year cracked down on urban disorder; Michael Dukakis, as a North-Eastern liberal and the Democratic nominee in 1988, chose centrist Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas as a political and geographical counterweight; in 2012, Republican nominee Mitt Romney, a technocratic former governor of Massachusetts, picked conservative Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan as his running mate.

For all this painstaking effort, I’m not sure a presidential candidate’s running mate makes any significant difference to the result of the election. In a sense, this is an obvious example of the contextual short-sightedness of political commentators and analysts. They (all right, we) might think “Well, when Harris was California attorney general she opposed a conservative definition of marriage, but Josh Shapiro is a conservative Jew who has been married for 27 years and has four children”. That makes some logical sense, but I don’t believe it’s how the vast majority of voters think. It rests on an assumption that the electorate pays vastly more attention to politics than they do, and approach even major choices like a presidential election with far more data than they do.

I could be wrong. Do Running Mates Matter?: The Influence of Vice Presidential Candidates in Presidential Elections (2020), by Christopher J. Devine and Kyle C. Kopko, concluded after exhaustive research that 80 per cent of voters in the 2016 election cited the identity of vice-presidential candidates as a contributing factor in their decision on how to vote. This feels plausible: if you were willing to give your support to the wild card which was Donald Trump, then you would have voted Republican, and I find it hard to believe that any doubters would have been tipped over the edge by Governor Mike Pence of Indiana. Equally, would anyone who was reluctant to vote for Hillary Clinton be reassured by former governor of Virginia Tim Kaine? Or, if questioned, do we naturally say that the running mate was an influencing factor because we want to seem wise, informed and considered?

Certainly I find it hard to point to any presidential election before 2016 and say with any confidence that the vice-presidential candidate on either side was a key factor. Senator Dan Quayle of Indiana was regarded as immature, lightweight and borderline-absurd but he became vice-president when George H.W. Bush won the 1988 election 40 states to 10. Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee was a college football coach, distinguished graduate of Yale Law School and well-known chairman of a (frequently televised) US Senate committee tackling organised crime, but his presence of the Democratic ticket did little to help former governor of Illinois Adlai Stevenson when they faced President Eisenhower and lost by 41 states to seven and nearly 10 million votes.

My instinct, therefore, is that while this fine-grained scrutiny is all good fun, if Harris is the Democratic nominee then her running mate will make little difference to her chances against Trump. Much more important will be public perception of the state of the economy, optimism or pessimism about the future, the importance to the voters of abortion rights, the way in which Harris can project a personality to the electorate, how well she can address major issues like immigration, unemployment in deindustrialised areas, social issues like the opioid crisis and what the global geopolitical situation is like at the time. All the same, if you asked me, I’d choose Shapiro for some solid achievements in state government or Kelly because he was literally an astronaut.

Harris will pound Trump in the debates

Politics is always prone to crazes and fandoms which bear relatively little relation to reality. Just as the now-departing Joe Biden is being hailed as “easily the best president that we’ve had since FDR” and dubbed “the best president of my lifetime. Full stop”, so Kamala Harris is being greeted by her more enthusiastic partisans as a politician of exceptional ability, vision and appeal. In particular, many supporters have pointed to her career as an attorney and a prosecutor to suggest that she would easily best Donald Trump in the next television debate, due to be held by ABC News on 10 September. I think this not so much mistaken and misguided.

In a conventional debate, Harris’s prosecutorial skills might be an advantage in a head-to-head debate. But that is not how Donald Trump approaches debates, as we have seen over two election cycles already. We know that he will lie readily, freely, extensively and without a flicker of scruple, and will simply shrug off any attempt to argue that he is in the wrong. He will largely ignore what his opponent says, and instead dwell on his chosen talking points and drive home his accusations against his opponent (whether they are true or not).

There are still many politicians in America who treat Trump as if he were like any other opponent. There was more than ample evidence in the 2016 campaign that he had torn up the rule book and any conventions or notions of decency, and would approach campaigning in his own distinctive way. To use the techniques of conventional politics, whether it is in debating or projecting a political message, simply will not work. Harris may have strengths which will allow her to land telling blows on Donald Trump’s candidacy, but be aware of and realistic about what they are.

Conclusion

As I said, this is merely a collection of observations, and they are observations and analysis of the presidential campaign as of 25 July. Just as we have had a dizzying and exhausting four weeks since that debate in Atlanta, so the next 14½ weeks until polling day will see a great deal happen, expected and unexpected. On balance I still think, as I have thought for at least a year, that Trump is likely to win a second term. It may be that he wins by a landslide. But I don’t expect the campaign suddenly to become boring.

![Vice presidential nominee Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge giving his acceptance speech at the rostrum during the Republican National Convention, Chicago, Illinois] / TOH. | Library of Congress Vice presidential nominee Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge giving his acceptance speech at the rostrum during the Republican National Convention, Chicago, Illinois] / TOH. | Library of Congress](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!F6I1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3e960ac1-182b-46a8-9b28-77324e9357e6_1024x695.jpeg)

I'm surprised you describe Kennedy as a "liberal" in the 1960 context. He actually ran to the right of Nixon on national security issues. Running mates have occasionally been decisive. Kennedy's choice of Johnson ensured that the Democratic ticket carried Texas which was decisive in a close election. Dukakis attempted to repeat the trick with Bentsen in 1988 but by then Texas had moved further into the Republican camp and George H.W. Bush was himself an adopted Texan. Trump's choice of Pence (Governor of Indiana, a Mid-Western state) probably helped to reassure Evangelicals who might have had doubts about a thrice married New Yorker, who had previously held liberal views on abortion. To win in 2024, the Democrats MUST carry Pennsylvania, Michigan, and either Wisconsin or Arizona. As a West Coast candidate, Harris is probably better placed than Biden to carry Arizona, a state which elected both a Democratic Governor and Senator in 2022. If Whitmer is eliminated on the grounds that you cannot (yet) have two women on the ticket, that leaves Shapiro. He has won state wide elections in Pennsylvania three times, most recently by 56-44. Incidentally, how is his number of children relevant?