The power of the happy warrior

Optimism is a potent weapon in politics, but it only has weight if it is authentic and in tune with the public mood

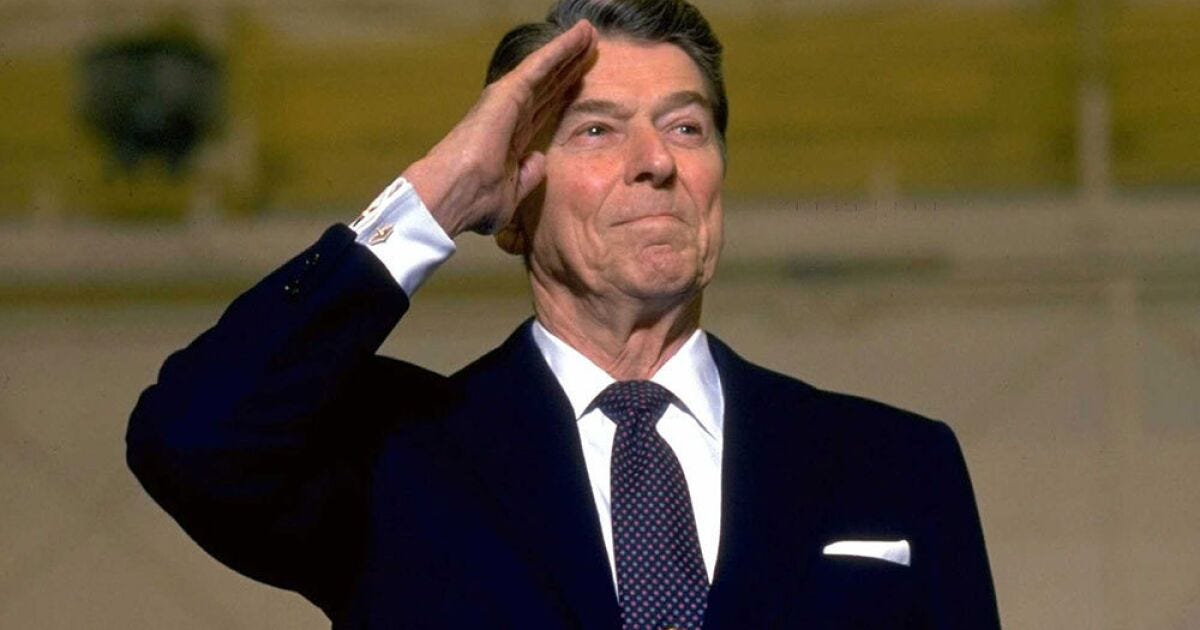

The recent announcement that Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States, would receive hospice care at home and was preparing for death—as I write he is still with us, aged 98 and the longest-living president in history—caused many historians to reassess his White House legacy. His reputation has traditionally been low; although he was personally pleasant and generally held to be well-intentioned, he was a one-term chief executive whose tenure was marked by a series of policy failures and missteps. Moreover he was defeated in the 1980 election by a man who would emerge as a transformative leader in global politics, Ronald Reagan. Yet many commentators, such as Noah Smith, the prominent journalist and blogger, argued that much of what Reagan was held to have achieved had in fact been set in train or planned under his Democratic predecessor.

Reagan has an incredibly strong brand image. Famously, he had enjoyed a career as an actor before turning to politics in the 1960s (on hearing of Reagan’s ambitions to public office, the great movie boss Jack Warner had exclaimed “No, Jimmy Stewart for governor, Ronald Reagan for best friend”) and it was taken as read that he was essentially a performer. This was slightly odd, as his acting career had never risen above indifferent, but it did, perhaps, account for ease in front of the camera and his ability assume a persona.

That character which carried him to the highest office in the land was, like many of the most successful performances, drew heavily on the truth. Reagan wanted to be seen as a straightforward, honest, open figure, described by Peter Robinson, his one-time speechwriter, as “the perfect Mid-Western gentleman”, emphatically not part of the political establishment; he was born in Illinois, his parents moving repeatedly within the state in his childhood, and educated at Dixon High School and Eureka College, a very homely academic background compared to some presidents. Overlying this honest simplicity was a fundamental optimism and cheeriness of nature, and it was that quality which appealed enormously to the American electorate at the end of the grim, punishing 1970s and led to Reagan being nicknamed “the happy warrior”.

(It was not an original sobriquet. It came from a poem by Wordsworth, The Character of the Happy Warrior, and was first used in a political context by President Franklin Roosevelt, who used the phrase to describe Alfred E. Smith, governor of New York, when proposing him as candidate for president at the 1924 Democratic Convention in New York. It was also applied to Hubert Humphrey, vice-president 1965 to 1969, and, by President Barack Obama, to his then vice-president, Joe Biden.)

The notion of Reagan’s sunny disposition was reinforced by a television advertisement used by Republicans in the 1984 presidential campaign. Entitled Prouder, Stronger, Better, it began with the line “It’s morning again in America” and made a simple pitch for the president’s re-election: after four years, the electorate simply felt better about themselves and their country, having seen the economy improve, America’s standing in the world restored and the Republican platform set out in simple, moral terms. The advertisement was devastatingly effective. Reagan defeated his Democratic opponent, former vice-president Walter Mondale of Minnesota, in a landslide that was nearly a whitewash: the president won 49 states, leaving Mondale only his home state (which he only carried by 0.18 per cent) and the District of Columbia. The result in the Electoral College was beyond emphatic. Reagan won 525 votes, Mondale just 13.

There is something fundamental in the American character to which optimism appeals. It is, after all, an idea as much as a country, and appeals to “the American dream” are a political commonplace. Barack Obama won the White House in 2008 under the slogans “Change we can believe in” and “Yes we can”, the latter becoming a chant at rallies, though it was in part cribbed from its Spanish equivalent, “Sí, se puede”, the motto of the United Farm Workers of America. John F. Kennedy had also campaigned on the theme of change and aspiration in 1960—perhaps ironically, as it was a bitter, nasty, closely fought and corrupt battle with the Republican vice-president Richard Nixon—promising to “get America moving again” and making much of his youth and vigour. Kennedy’s age, 43 years old, and his smiling good looks obscured the fact that his opponent was only 47, hardly a senior citizen, and had been elected vice-president in his 30s.

The most obvious parallel in recent British politics has been Boris Johnson. His election as mayor of London in 2008 played heavily on optimism and good humour. One of his early biographers, Sonia Purnell, quotes a widely held reason for supporting him as “I’m voting for Boris because he is a laugh”. When he ran for leader of the Conservative Party in 2019, amid savage internal wrangling over the decision to leave the European Union, he did his best to remain upbeat, and offered the voters a simple, easy-to-understand offer, that he would “deliver Brexit on 31 October” and would “do better than the current Withdrawal Agreement that has been rejected three times by Parliament”.

His party’s victory in the December 2019 general election continued that theme of simplicity, campaigning under the slogan of “Get Brexit done”, which appealed to an electorate weary of arguments which had been raging for more than three years since the referendum in the summer of 2016. One very earnest study of non-verbal messaging in the campaign referred to Johnson’s “superficially clownish behaviour” and “unique performative style”. This demeanour, the pose of a slightly baffled but well-meaning aristocrat who can’t quite understand what all the fuss is about, helped him to deliver prima facie harsh, negative attacks on his opponents, especially Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, without seeming bitter or partisan.

I think Johnson is, however, slightly different from Reagan, Obama or Kennedy. There is an air of meanness about Johnson’s clowning. It is very obviously an act, though one must concede that it is a thorough one and the mask almost never slips, and is buttressed by his cast-iron imperviousness to embarrassment. When, as mayor, he became stuck on a zip-wire in Victoria Park during the London Olympics in 2012, waving two large Union flags, he at least pretended to take it on the chin so convincingly, shouting “This is great fun but it needs to go faster”, that many wondered if it was a stunt. I remember discussing the incident with colleagues in the House of Commons, and our common conclusion was that it would have been a presentational disaster for literally any other politician. For Johnson, it was simply another photo opportunity.

The former Conservative leader is always careful not to seem like a bully. In person he can be intensely charismatic, almost mesmerising, and has the capacity to buoy up others and make them think that whatever they are persuaded to do is the obvious course of action. But he is a showman and a show-off. His is the pose of a man who dislikes sharing the limelight, which is one reason he was repeatedly such an impossible colleague on his journey up the ladder of success. His stint as foreign secretary from 2016 to 2018 was little short of dire, while Michael Howard, as leader of the opposition, had to dismiss him as shadow culture minister when he was found to have lied to the media about an affair with journalist Petronella Wyatt (he initially called the accusations “an inverted pyramid of piffle”, but they proved to be entirely accurate).

And yet… although his supposed electoral pull has been vastly overstated, and there is very little evidence that he personally added much to the Conservative Party’s level of support in the 2019 general election and afterwards, he retained until quite late in his premiership a sort of grudging or despairing likeability, sometimes among voters who were very far from natural Tories. Focus groups in 2019 described his “charm” and “personality”, regarding him as “one of the lads” (as inaccurate a description of Johnson as it is possible to give), one person saying “he can charm people, he can speak to people and he will be able to sway people to back him”.

Johnson’s broad popularity is now spent. He retains a fierce degree of support among some MPs and party members, but the shine went off him long ago. As was inevitable, the characteristics which made him attractive—ebullience, unshakeable self-confidence, a willingness to ignore the laws of political gravity—have now become monstrous flaws. The idea which was floated briefly after Liz Truss threw in the towel as prime minister that he might be restored to Downing Street, while it caught the imagination of many because of its drama, never really seemed like the stuff of reality. As he continues to be investigated by the House of Commons Committee of Privileges for misleading the House, even some of his fanatical supporters have fallen away or conceded that he is a lost cause. His three-year premiership (is it really only that?) seems like an experiment that the Conservative Party will not soon repeat.

One leader who relied heavily on a projection of optimism and better days to come was Tony Blair. Indeed, the theme song which accompanied Labour’s historic 1997 general election victory was Things Can Only Get Better by D:Ream, an otherwise-forgettable dance group (though their keyboard player, Brian Cox, would have an unlikely second career as professor of particle physics at the University of Manchester and a popular science figure). Blair was a lucky politician—which is no criticism, as luck is an essential part of success in any field—lucky to be placed on the shortlist for the then-impregnable Labour stronghold of Sedgefield at the last minute in 1983; lucky to find himself sharing a House of Commons office with another new Member, Gordon Brown, a rather dour intellectual steeped in the more cerebral traditions of the Labour Party; lucky to be handed the job of shadow home secretary in 1992 as the Conservatives’ grip on law and order as a policy area was loosening; and, to be brutal, lucky that the Labour leader John Smith died suddenly in 1994, opening up the top of the party only three years before a general election which was Labour’s to lose.

Nevertheless, Blair made the most of his luck. He was never a deep thinker: he had been a poor pupil and a general irritant to masters at Fettes, and his time at St John’s College, Oxford, was academically undistinguished. He was called to the Bar in 1976 and practised employment and trade union law with a similar lack of distinction, in contrast to his fellow barrister and future wife, Cherie Booth, who went on to take silk at the age of 40 and become an internationally recognised human rights lawyer. But Blair was, one senses, always looking simply for a springboard. Although he had shown no interest in politics at all at university, he had read the first volume (it is very Blairite only to have read volume one) of Isaac Deutscher’s biography of Leon Trotsky, and this experience, “like a light going on”, gave him “the notion of having a cause and a purpose and one bigger than yourself”. That, arguably, was the first fuel of his wide streak of messianic zeal which would come to affect his later years in office.

These drawbacks, if drawbacks they were, would also prove part of his “happy warrior” persona. His early enthusiasm for Trotsky notwithstanding, he travelled light in ideological terms. In the early 1980s he was identified with the “soft left” of the Labour Party, at that time the creed of the party’s ageing leader, Michael Foot, a brilliant, witty, erudite gadfly but hopelessly miscast as a potential prime minister. But it became clear, almost as soon as he was elected to the House of Commons, that his conception of Labour’s future was radically different. Even before the necessary agonies of the miners’ strike, he urged his party to accept some of the Thatcher revolution, arguing that Labour had lost sight of the interests of those whom they were supposed to represent, the urban working classes.

Blair did not, of course, come from these roots himself; his father, Leo, had been a barrister and law lecturer at the University of Durham before suffering a serious stroke (and had ambitions to stand for Parliament himself—as a Conservative) while his mother, Hazel, a Protestant from Donegal, was the daughter of the master of Carricknahorna Orange Lodge in Cashelard. Blair had enjoyed a conventional public-school-and-Oxford education before moving into the law. This lack of Labour heritage, though used often enough as a weapon against him, enabled him to transform his party’s fortunes.

As he rose to prominence, Blair initially proved strangely elusive for satirists and cartoonists (though the impressionist Rory Bremner quickly nailed both the voice and the mannerisms). But there was a constant theme. Spitting Image, in its dying days when Blair became leader of the opposition, portrayed a small character with a wide, toothy smile; Private Eye turned him into an earnest trendy vicar writing a parish newsletter; cartoons often owed a debt to John Tenniels’s Cheshire Cat. This represented an essential truth about him: eager to be liked, he projected a sense of hopefulness and bounce, a feeling—as Reagan had done to great effect—that tomorrow would be better than today. When he took office in 1997, he was the youngest prime minister since the Earl of Rosebery in 1894, the first to have been born after the Second World War, and he had a young family and a relaxed style which made him relatable.

None of this was accidental. I wrote in 2021 that I had heartily despised Blair when he was in office but in recent years had come to see many of his virtues (without losing sight of his faults). But in terms of reviving the Labour Party, he and Peter Mandelson were the only figures who truly grasped what needed to happen: that the party needed to reinterpret its contract with the electorate and make it clear that it was not viscerally or ideologically opposed to success and personal prosperity; that its previous, jealous view of the State as a reinterpretation of extra Ecclesiam nulla salus no longer applied. From these conclusions, an upbeat, optimistic approach inevitably flowed.

Alastair Campbell, Blair’s long-time director of communications, described his boss as “a major optimist who makes you feel that seemingly impossible change can come”. That was central to the Labour victory of 1997. If a defining image of the previous general election in 1992, at which the Conservatives had unexpectedly triumphed, was their poster warning of “Labour’s tax bombshell”, then in 1997 it was surely Blair’s early morning speech to crowds of supporters on Friday 2 May once it was clear that Labour had won, and won by a landslide. In an atmosphere thick with emotion, after 18 years of Conservative government and times at which it seemed Labour faced an existential threat, his first words to his audience were “A new dawn has broken, has it not?” It could—arguably should—have sounded cloyingly mawkish and melodramatic, with its strange Biblical cadence, but this was Blair at his matchless peak. Instead it sounded like a benedictus for New Labour and the beginning of a new era; the light of dawn, as he rightly saw, after a long and dark night.

Blair’s good fortune was to be a happy warrior at a time when it was the mood the electorate craved. It’s a note which many political leaders try to strike but few really succeed: John Major, though well-intentioned, was desperately unlucky in his premiership and in any event always cursed with a faint echo of Charles Pooter, both in manner and voice, while Margaret Thatcher’s version of optimism was much more the bracing encouragement of nanny or the rousing sermon of the mission hall. Edward Heath was intellectually aware of the concept but the sight of him laughing, shark-wide grin and shoulders heaving, was so monstrous that it was an instant tell for impressionists. Harold Wilson, while he spoke the language of modernity and progress, was altogether too sly and suspicious, and perhaps too clever, to seem a sincere ambassador for a brighter future.

We are very cynical nowadays and often view politics as an exercise in deception and disingenuousness. The truth is that it is an unsteady balancing act between telling the electorate what they want to hear and what they need to know. Achieving that balance relies partly on lucky, but partly too on a sensitivity to the public mood. Thatcher intuited that the country was in an emotional slump, exhausted and demoralised, despairing of the future, and her exhortatory style was ideally suited to change minds and behaviour. Blair was gentler, an arm around the shoulder rather than an arm up the back, but it was judged to perfection, and the parliamentary arithmetic bore that out.

Optimism is a potent force. People are at their best when motivated by hope and the notion of future success and prosperity. But it has to be authentic and natural. It cannot successfully be forced. It does not, for example, come naturally to Sir Keir Starmer, which is why the opposition’s current substantial poll lead is still widely thought to be soft and vulnerable. But at least he hasn’t tried to fake it: instead he is relying on his seriousness of purpose and air of reliability, developed as director of public prosecutions. Rishi Sunak aspires to a lightness of touch, but he is still inexperienced and the sound does not always carry from the depth of the electoral hole in which the Conservatives find themselves. I don’t expect the next election campaign to be an inspiring or uplifting one, rather a series of exchanges of fire from within entrenched positions. Perhaps by 2029, whoever is at the helm of the two major parties, British politics will have found itself another happy warrior. There are times at the moment when it cannot come too soon.

May I be excused a possibly tangential comment about President Carter?

He was an extraordinarily brave man. When the Chalk River Laboratories reactor in Ontario suffered a meltdown in December 1952, it was Carter – a US naval officer and nuclear engineer – who went inside the reactor to disassemble the damaged core. You can read the full story in the Washington Post, here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/02/20/jimmy-carter-nuclear-reactor-navy/?pml=1

No. Its the policy of a fool.