The Kennedy assassination: JFK 60 years on

It is the 60th anniversary of the death of John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States, and the shadow of that day is immeasurably long, in all sorts of ways

If you are reading this on Wednesday (22 November 2023), then you might want to pause just for a second at 6.30 pm Greenwich Mean Time. At that moment, exactly sixty years before, the world changed. Just beforehand, in central Dallas, Nellie Connally, wife of the governor of Texas, John Connally, turned around in the 1961 Lincoln Continental convertible in which she was a passenger to talk to the 35th President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

“Mr President, they can’t make you believe now that there are not some in Dallas who love and appreciate you, can they?”

“No,” the president replied. “They sure can’t.”

They were his last words. A series of shots rang out—how many, from where, fired by whom are the centre of JFK lore—and within half an hour, the president was pronounced dead. The world had changed forever. It is easy for those who don’t remember the event, as I do not, to allow our inner cynic to regard the mythology as being overblown and sentimental, but it really was a cataclysmic blow. Just watch Walter Cronkite, the anchor of CBS news, announce the death to the viewing public. Cronkite was hardly a shrinking violet. He had reported from North Africa and Europe in the Second World War, including landing by glider during Operation Market Garden, and had looked into the face of genuine evil at the Nuremberg Trials, before being recruited to television news by the legendary Ed Murrow. Yet you can see the devastation in his face, hear it in his voice. This was, for countless millions, the day the dream died.

I’m not a JFK obsessive, nor do I have a more-than-average susceptibility to conspiracy theories. (A very old university friend told me he thought everyone should believe one conspiracy theory.) Indeed, although I find them fascinating, they can be corrosive and sinister, as we find every day in contemporary politics. For a concise assessment, I heartily recommend this episode of the excellent podcast Behind the Spine, which features Professor Sir Richard Evans, former Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge, talking about conspiracy theories. Nevertheless, I know a lot about history, and the Kennedy assassination is a significant event in the post-war period, so I have, I suppose, accumulated a lot of knowledge about it almost without trying.

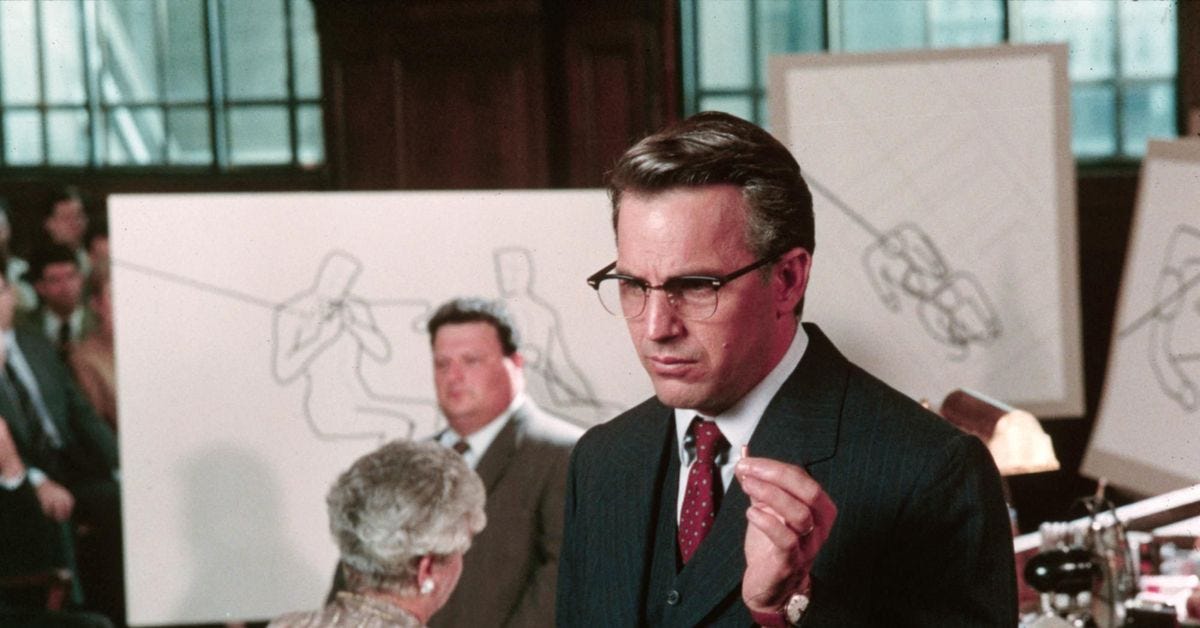

I am not, and I hope this isn’t too disappointing, going to reveal who was responsible for the assassination. It has given birth to a media-entertainment-history-activism industry, from the moment the shots in Dealey Plaza rang out, and was then supercharged by the release in 1991 of Oliver Stone’s epic 206-minute JFK. I’m rewatching the film as I write this; it is a magnificent absurdity, three-and-a-half hours of dramatic claims, plausible questions, scene-chewing performances and preposterous hairpieces. Stone is an extraordinary man. Undoubtedly a director of rare talent, as Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July and Natural Born Killers demonstrate, he is also an obsessive and a polemicist who has championed dubious figures like Hugo Chávez and Vladimir Putin. This has sometimes tipped him over into crank territory, as when in 2010 he attempted to “contextualise” Hitler and Stalin; like so many people who are definitely not anti-Semitic seem to do, he had to clarify earlier statements he had made and stress that “Jews obviously do not control media or any other industry”. (I am aware that Stone’s father Louis, born Silverstein, was Jewish. It doesn’t mean Stone cannot be anti-Semitic.)

There are some things I can tell you with reasonable certainty. Lee Harvey Oswald was not the only gunman, and it is very unlikely that he fired the fatal shot. The report of the Warren Commission, the body of eminent men chaired by chief justice of the United States Earl Warren, and including future president Gerald Ford and former director of the CIA Allen Dulles, is so flawed as to be hopeless in terms of its conclusions. Warren himself, a former governor of California, was as much a politician as a judge, and he was a dull man and a fairly mediocre jurist. And while the Warren Commission’s findings were largely trashed by the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations, set up in 1976 and chaired by Rep Louis Stokes, an able and respected African-American lawyer from Ohio, you won’t find a definitive answer in that committee’s conclusions either. Sorry.

The Kennedy assassination as a narrative device

The assassination of John F. Kennedy is a catalyst for so much. It allows those who enjoy this sort of thing to rail against the Deep State and construct enormous, complicated conspiracies involving the CIA, the Mafia, the Soviet Union, Cuba, the “military-industrial complex” (a phrase coined in 1961 by retiring president Dwight D. Eisenhower) and anyone else you wish to pull in. It tells us the reassuringly alarming story that our masters have lied to us for decades and continue to do so. And it is a gift for counter-factual historians of all kinds.

Kennedy wouldn’t have taken the United States into Vietnam! Well, hold on: it is true that for a long time Kennedy did not anticipate the large-scale deployment of US combat forces. In 1962, his secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, told Congress that the administration believed:

to introduce US forces in large numbers there today, while it might have an initially favorable military impact, would almost certainly lead to adverse political and, in the long run, adverse military consequences.

American policy was to support the Republic of Vietnam and its president, Ngô Đình Diệm, against the communist insurgency of the Viet Cong in the north of the country. But the commitment was unwavering. After the summit with Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev in Vienna in June 1961, Kennedy had told James Reston of The New York Times, “Now we have a problem making our power credible and Vietnam looks like the place”.

This “military assistance” was no small affair. President Eisenhower had sent 900 advisers to Vietnam; by November 1963, Kennedy had authorised the deployment of 16,000 US personnel. Still advisers, but that is a larger commitment than, say, the United Kingdom made during the Korean War (just over 14,000). The CIA gave its blessing to the coup which ousted President Diệm a few weeks before Kennedy’s death, and, while the president was supposedly shocked at the subsequent murder of Diệm and his brother, he congratulated the US ambassador in Saigon, Henry Cabot Lodge, for rapidly treating with the instigators of the coup.

The truth of Kennedy’s intentions was disclosed in the speech to the annual general meeting of the Dallas Citizens Council which he wrote but never delivered: it was in his programme for 22 November 1963. He spoke, or would have spoken, passionately in support of US assistance to the government of Vietnam, and the essential nature of the struggle.

Our security and strength, in the last analysis, directly depend on the security and strength of others, and that is why our military and economic assistance plays such a key role in enabling those who live on the periphery of the Communist world to maintain their independence of choice. Our assistance to these nations can be painful, risky and costly, as is true in Southeast Asia today. But we dare not weary of the task.

It is true that the advisers deployed by Kennedy were responsible for training soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). The attitude of the military leadership in Washington was that the US should remain focused on this task, and that the focus of policy should be the pacification of the north of Vietnam and the winning of hearts and minds. General Paul Harkins, commander of the Military Assistance Command—Vietnam, predicted victory by Christmas 1963.

Many point to National Security Action Memorandum 263, approved by Kennedy on 11 October 1963, as proof of the president’s intentions. This document predicted that better training for the ARVN would allow the majority of US advisers to be withdrawn by the end of 1965, and approved the immediate removal, not to be announced publicly, of 1,000 military personnel. There are two points here: the first is that the withdrawal of the advisers was entirely contingent on the (wildly optimistic) prediction that the ARVN would be self-sufficient by the end of 1963. It was not a principled statement of intent to pull out of Vietnam. And the withdrawal of 1,000 advisers still left 15,894 US personnel in Vietnam. I read recently a suggestion on social media that Lyndon Johnson, the villain of many Kennedy fantasies, countermanded this order immediately after assuming the presidency under National Security Action Memorandum 273. In fact, NSAM 273 merely reiterated Kennedy’s NSAM 263: the US would withdraw if the conditions it expected to be fulfilled were met.

Did Kennedy want to withdraw from Vietnam? Of course he did: but only in the context of victory. He had emphasised again and again the importance of the conflict in Vietnam in wider global terms, a stand the US had to take. On the assumption that the ARVN would be capable of controlling the security situation by the end of 1965, he looked forward to “mission accomplished” and the redundancy of the US military advisers. But to assume that Kennedy would have ended the US commitment irrespective of the situation on the ground is a massive leap of faith. McNamara came to the conclusion by early 1966 that the war was unwinnable, but President Johnson did not make that leap; as we know now, the last US Marines left the Saigon embassy by helicopter on 30 April 1975.

(I acknowledge humbly Robert Dallek’s 2003 article in The Atlantic, “JFK’s Second Term”, but would just venture that there are a lot of ifs and supposes.)

Kennedy would have pushed harder on civil rights! Hold your horses. Jack Kennedy was a New Englander, and his understanding of the struggle for civil and political rights was steeped in the experience of the Irish immigrant population in Boston. Undoubtedly he was in favour of desegregation, and disliked the fact that, by the time he became president in January 1961, many southern states were still defying the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that had ruled segregation in public school unconstitutional. During the presidential election campaign he had been outspoken in his protest at the arrest of the Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr at a sit-in in Atlanta, when Eisenhower had refused to intervene and Vice-President Richard Nixon, the Republican candidate for the White House, had stayed largely silent. King’s father endorsed Kennedy as a result.

Initially, however, Kennedy was lukewarm on civil rights. He feared that the activism of the movement would anger many Southern whites, and also realised that he was heavily reliant on Southern Democrats in Congress to pass legislation. He had served in the Senate with powerful figures like Richard Russell (Georgia), Sam Ervin (North Carolina), James Eastland (Mississippi), John Stennis (Mississippi), J. William Fulbright (Arkansas) and Strom Thurmond (South Carolina), the last of whom had conducted the longest ever filibuster, a monstrous 24 hours and 18 minutes, by a single senator to hamstring Eisenhower’s Civil Rights Act of 1957. Sam Rayburn of Texas was still speaker of the House of Representatives, having served from 1940 to 1947, 1949 to 1953 and since 1955 (he would retire at the end of 1961). In the background lurked the 78-year-old James Byrnes, former senator, Supreme Court justice, secretary of state under President Truman and then governor of South Carolina, who was in some ways the keeper of the South’s political conscience.

This is not to say Kennedy did nothing for civil rights. In March 1961, he issued Executive Order 10925 which established the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and required government contractors to ensure that employees “are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin”. He reluctantly deployed federal troops to Mississippi in September 1962 to enforce the enrolment of James Meredith, a young African-American student, at the all-white University of Mississippi (though his brother Robert, the attorney general, was much more active in this issue). In November 1962, he signed Executive Order 11063 to forbid racial segregation in federal housing. And he made some significant federal appointments like that of prominent civil rights attorney Thurgood Marshall to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961.

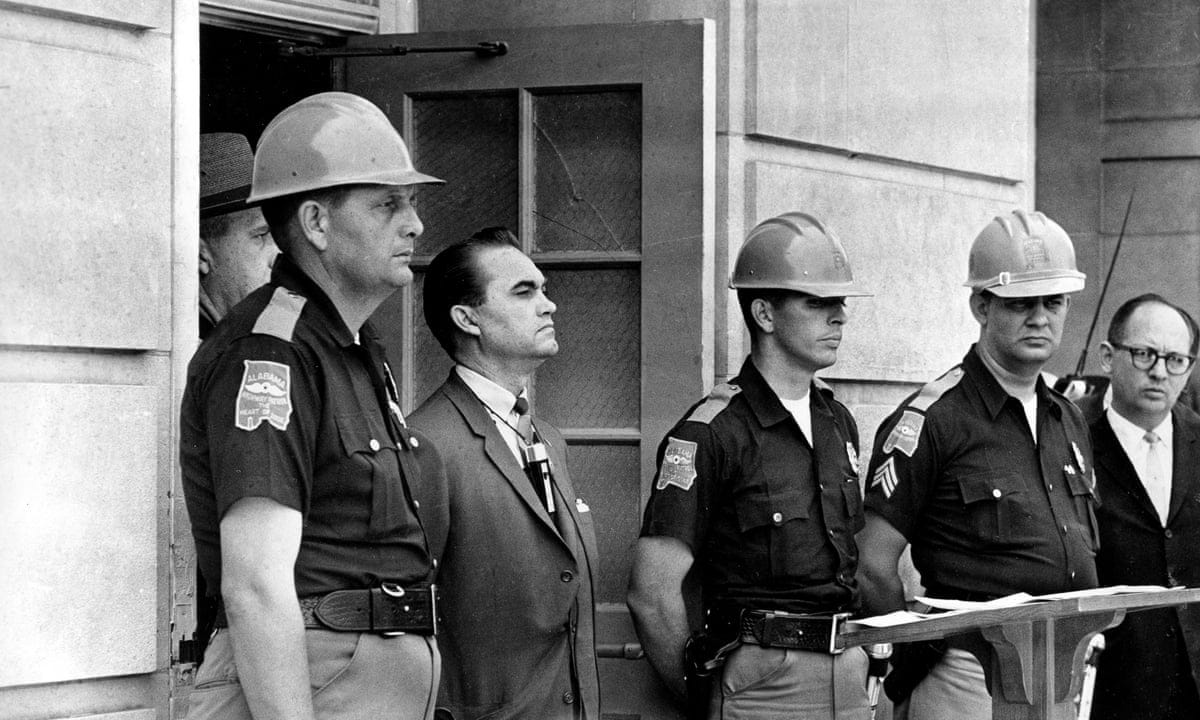

Kennedy became more active in 1963. In June, he federalised the Alabama National Guard to remove the governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who had been physically preventing two African-American students enrolling at the University of Alabama. That evening, 11 June, he gave a televised speech in which he reframed civil rights, from his point of view, as a moral cause.

We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it… but are we to say to the world, and, much more importantly to each other, that this is the land of the free except for the Negroes?

From this speech, he moved forward legislatively, and sent a draft Civil Rights Bill to Congress on 19 June, where it was quickly referred to the House Judiciary Committee under Rep. Emanuel Celler, a veteran Democrat congressman from New York.

August saw the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, otherwise known simply as the Great March on Washington, at which King, standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech to 250,000 marchers. It was an iconic moment, so much so that Motown founder Berry Gordy released a recording of King’s address as a single. But Kennedy was initially against the march. He was anxious that such a large and defiant demonstration would antagonise Congress, and his FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, had presented him with evidence that some of King’s closest advisers were communists. Robert Kennedy authorised the FBI to tap the telephones of King and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. While the march was in the end peaceful, and Kennedy was impressed by its organisation and by King’s speech, his underlying anxiety was obvious.

This was all having an effect. In September 1963, a Gallup poll showed that the president’s approval rating in the South was only 44 per cent, compared to 62 per cent nationally. The day after his televised address, 12 June, a motion to extend funding for the Area Redevelopment Administration was unexpectedly defeated in the House of Representatives by 209 votes to 204, and the House majority leader, Rep Carl Albert of Oklahoma, told the president plainly that it had been undone by Southern Democrats angered by his stance on civil rights. (To his credit, Kennedy reflected, “But of course, I had to give that speech, and I’m glad that I did.”)

The narrative that some Kennedy fans want to believe in is that JFK was the liberal hero, a kind of Wilberforce-Brown-Lincoln figure who would have been the consummation of every dream of the civil rights movement. What more noble cause could Camelot have espoused? And there is certainly no indication that Kennedy was anything but well-intentioned on the issue. When he did act, he did the right thing, and by the summer of 1963 he had turned his oratorical power towards civil rights. Nevertheless, he was an astute politician. He knew that he was not loved by the South, much less by Southern Democrats, and he knew too that this was a force that threatened his ability to legislate.

It is certainly hard to argue that civil rights were fundamental to the goals of his presidency which he had set out in his captivating inaugural address in January 1961. Ted Sorensen, Kennedy’s chief speechwriter and “intellectual bloodbank”, looked back at the speech in The Guardian in 2007, setting out what he thought JFK’s priorities were, and arguing that he achieved them; the kind of reforms the Civil Rights Act of 1964 enshrined were not among them. His draft bill of June 1963 may have laid the foundations of the next year’s act, but he still exhibits the kind of political caution which a good president should have.

My more cynical side wonders if those who seek to portray Kennedy as the hero of civil rights do so because the real hero, the man who did the work and took the risks, was the much less attractive figure of Kennedy’s vice-president and successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson. LBJ was a Southern Democrat par excellence, who had been Democratic leader of the Senate from 1953 to 1961, and as Robert Dallek has observed, “There was no more powerful majority leader in American history”. He was a brilliant legislator, a man who could get things done, a physically intimidating figure at nearly six-foot-four whose leadership style was, in the words of one contemporary, “an incredible blend of badgering, cajolery, reminders of past favors, promises of future favors, predictions of gloom if something doesn’t happen”.

He was not a nice man. Johnson was a bully, a cynic, a manipulator and a racist. Yes, racist: one can, very reasonably, point to the milieu in which Johnson grew up, the white supremacist atmosphere of early 20th century small-town Texas, and in mitigation point to his civil rights achievements (of which more in just a moment). But there was an ingrained racial prejudice in Johnson which he didn’t seem to fight all that vigorously. Talking to fellow Southern Democrats about civil rights legislation, he would refer simply to “the nigger bill”, and even in relatively polite society he tended to talk of “nigrahs”. As his biographer Robert Caro records, he had talked in the late 1940s of Asians as “hordes of barbaric yellow dwarves”, and a favourite prank, based on the idea that African-Americans were peculiarly afraid of snakes, was to keep such a reptile in the boot of his car and, stopping at gas stations, try to trick African-American pump attendants into opening the boot.

Perhaps the duality in Johnson is summed up by his appointment to the Supreme Court of Thurgood Marshall, whom Kennedy had put onto the Court of Appeals. Asked why he had chosen Marshall, then solicitor general and the government’s chief counsel in appearing before the Supreme Court, he said tersely, “when I appoint a nigger to the bench, I want everybody to know he’s a nigger”. Distasteful? Of course. Cynical? Without question. But Marshall was the first African-American justice (only two others have followed, Clarence Thomas, nominated in 1991, and Ketanji Brown Jackson, nominated in 2022), and that appointment stands to the credit of Johnson. Whether LBJ believed to his core in civil rights, the simple fact is that he, and no-one else, oversaw the architecture of civil rights: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Economic Opportunity Act, the Voting Rights Act, Executive Order 11246 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Would Kennedy have done all of this? Maybe. Would he have had the leverage with Southern Democrats to do it? Maybe not. Like one-time Red-baiter Richard Nixon recognising the People’s Republic of China, perhaps it took someone from within the conservative, segregationist South to make the revolutionary changes on civil rights. But it is no slam-dunk that JFK would have been the hero his overbearing successor turned out to be.

Why was Jack Kennedy in Dallas?

It might be worth just reflecting for a moment on the circumstances of President and Mrs Kennedy’s visit to Texas in November 1963. As mentioned earlier, Kennedy’s support for civil rights, even if it had taken some time to flower fully, had cost him popularity in the South. His victory in 1960—a desperately close-run thing which was affected, perhaps even swung, by electoral fraud—had come despite his Republic opponent, Vice-President Richard Nixon, winning Florida, Tennessee, Oklahoma and Kentucky, while Senator Harry Byrd, the white supremacist, segregationist (Democratic) senator for Virginia, who was not even formally on the ballot, received Electoral College votes from unpledged Democratic electors in Mississippi (eight), Alabama (six) and Oklahoma (one). This was a serious battering for the Democrats in a winning year.

Texas had voted Democrat in 1960, but even with Johnson on the ticket, it had been fearsomely close, Kennedy taking the state 50.5 per cent to 48.5 per cent, a margin of 46,257 votes in a state with an electorate of 2.3 million. Dallas itself had voted for Nixon. The administration was in such bad odour in the city that Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic nominee for president in 1952 and 1956 whom Kennedy had appointed US permanent representative to the United Nations, had been booed, jostled and spat at only the previous month. While the crowds were more enthusiastic for Kennedy, as Mrs Connally observed to him just before he was killed, her remark served to show why the Kennedys were here. An election might be a year distant, but the prospect of losing it was real.

There was also a specific internal party reason. In 1963, the Texas Democratic Party, an affiliate of the national party founded in 1846, was split between liberals and conservatives, and the division had played a significant part in Dwight Eisenhower, born in Texas although raised in Kansas, carrying the state in 1952 and 1956. Two of the state’s leading figures, Senator Ralph Yarborough and Governor John Connally, were at loggerheads. Yarborough was in the motorcade in 22 November, but two cars back from the president, in a car with Vice-President Johnson. Connally was a close friend and ally of LBJ’s, and had served as secretary of the Navy until resigning in December 1961 to run for governor. He was a conservative, unlike Yarborough; such a conservative, in fact, that he became secretary of the Treasury under Richard Nixon (1971-72), joined the Republican Party in 1973 and was a serious contender for the GOP presidential nomination in 1980, raising more money than any other candidate. (He declined the offer to become Ronald Reagan’s secretary of energy.) Kennedy, Johnson and Connally had met in El Paso in June and agreed the presidential visit to Texas, and Kennedy regarded it as the informal start of his re-election campaign.

Would Kennedy have won re-election? Dazzled by the mythology, it is impossible to imagine otherwise. Post-war US history does show that only Carter, Bush 41 and Trump were one-term presidents strictu sensu; but Harry Truman (1948) and Johnson himself (1964) only won a single presidential election, while Gerald Ford won none at all. So in fact the two-time winners were Eisenhower, Nixon, Reagan, Clinton, Bush 43 and Obama.

On the credit side for Kennedy were his enduring personal appeal (in some parts of the US), a powerful campaigning persona, incumbency and an administration which had real achievements to point to: the first American in space, a diplomatic victory over Soviet missiles in Cuba and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. After a recession in 1960, the economy had performed strongly, with GDP and employment both growing and inflation remaining very low. There had also been progress on civil rights, though that played differently according to region.

On the other hand, in foreign affairs, the communist régime in Cuba had if anything been strengthened, rather than weakened, by the disastrous attempted invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. Later that year, the Warsaw Pact had caught the West off-guard with the erection of the Berlin Wall (excuse me, the Antifaschistischer Schutzwall, or Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart). And the civil rights movement had antagonised not only out-and-out racists but conservatives who viewed the disorder it brought with anxiety.

In reality, Johnson beat Republican challenger Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona by a landslide in 1964. Goldwater won only six states, but look at which ones they were: his home state of Arizona, then Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina. Southern Democracy was dying, and Richard Nixon would deliver the coup de grâce in 1968. It seems likely that Kennedy would have beaten Goldwater, though some of Johnson’s victory was surely support for the memory of the fallen president. But it did not seem that way in 1963, when Air Force One landed at Dallas Love Field at 11.40 am on 22 November. The clock was ticking. John Fitzgerald Kennedy had 50 minutes left to live.

Conclusion

I cannot begin to imagine how many millions of words will be written on JFK today and hereafter, to add to the many millions already set down. I hope this has provided an insight into some of the less-often-explored aspects of the assassination, and perhaps poked some sacred cows into lowing. The president’s death did change everything, I think that’s fair. But it is not the morality tale as which we too easily read it. In fact, history never is.

If you are still craving Kennedy content, please watch and/or listen to a special episode of the excellent podcast Behind the Spine, in which Mark Heywood, writer, presenter, consultant and all-round great man, interviews imagery analyst and soldier Mark Taylor about the assassination and what the evidence tells us. And they’ll tell you who killed JFK.

As a Brit his murder doesnt have such great symbolism, nor do many of the issues discussed. My late Irish mother probably held him in greater affection than I. The Irish American link and often innate anti Brit sentiment bond those two nations. Perhaps we are a more cynical people, we dont gave a dream or some myth of righteous leaders taking us to the promised land. USA was founded by white christians looking to build the impossible, a shangri la here in a temporal and infinitely fallible world. I wonder if he had died of a heart attack whilst in office, how different his memory would be? The method of his death and the lingering shadow are what gives his memory much of its power. JFK wasnt perfect. Who is? If he had lived and gone on to retire and pass of age, would be any more of a symbol than say Woodrow Wilson ?