The imperial presidency: Nixon to Trump

Fifty years ago today, Richard Nixon resigned as President of the United States, a unique act: what drove him from office would not make Donald Trump blink

At 11.35 am on Friday 9 August 1974, 50 years ago today, the White House Chief of Staff, General Alexander Haig, handed a short letter to the United States Secretary of State, Dr Henry Kissinger. It was from President Richard M. Nixon, and read simply “I hereby resign the office of President of the United States.”

Kissinger initialled the letter to acknowledge receipt and noted the time, and Vice-President Gerald Ford, who had only been in office for eight months, became the 38th President. For the first (and so far only) time in the history of the United States, a president had voluntarily given up his position. The circumstances leading up to that unique event half a century ago illustrate a stark contrast with contemporary American politics.

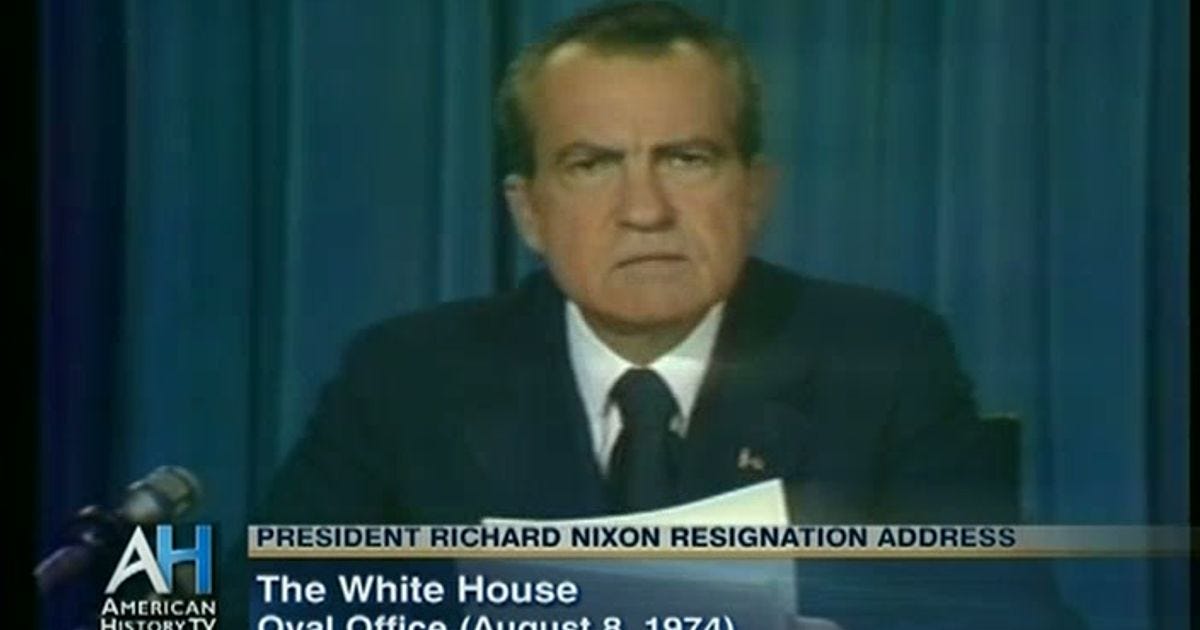

Nixon had finally decided to resign two days before, and on the evening of 8 August he had broadcast to the American people from the Oval Office informing them of his intention. He had been president for more than five years, winning a crushing re-election victory in 1972 over his Democrat opponent, Senator George McGovern of South Dakota, and carrying 49 of the 50 states. But the events which led to his downfall had already taken place, in June 1972, when five individuals later linked to Nixon’s re-election campaign had broken into the Democratic National Convention’s premises in the Watergate Hotel and Office Building in Washington.

The story of Watergate is well known and can be read exhaustively elsewhere. Nixon neither sanctioned nor knew about the break-in in advance, but once it became public he certainly had no compunction in trying to conceal his administration’s involvement. For him, politics was a no-holds-barred affair, and any scruples he may once have possessed had been beaten out of him in his failed bid for the presidency against Senator John F. Kennedy in 1960. As the Watergate scandal unfolded, the House Judiciary Committee and a specially created Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities began investigations, and the President’s attempts to evade their jurisdiction succeeded only in miring him further in scandal. But the game changed on 5 August.

After months of wrangling, on that day the White House eventually complied with a subpoena from the House Judiciary Committee to release audio tapes of conversations which had taken place in the Oval Office. A recording system had been installed in February 1971, and it was voice-activated because Nixon was too physically clumsy to be relied upon to switch a device on and off. The result was that it captured everything. One recording, the so-called “Smoking Gun” tape, revealed that Nixon had been actively involved in the cover-up from a few days after the burglary, contrary to previous public statements. He had lied, and he had been caught out. His remaining political support all but collapsed.

It was now inevitable that articles of impeachment against the President would be introduced into the House of Representatives, and after the release of the “Smoking Gun” tape, the 10 Republicans on the Judiciary Committee said they would vote in favour of them. Nixon would then be tried by the Senate, which would need a two-thirds majority, 67 votes, to convict him and remove him from office. On 7 August, Republican congressional leaders told the President there were no more than 15 senators in the party who would be guaranteed to vote against his conviction. It was all over. Nixon knew he had to resign.

Only one president before Nixon had faced impeachment, Democrat Andrew Johnson who had been impeached in early 1868. Johnson had been found guilty by a majority of senators, but those seeking to remove him from office ended up one vote short of the required two-thirds of the Senate. The spectre of the process remained, however, a constitutional crisis of almost unimaginable magnitude.

Even his staunchest defender would not claim Richard Nixon was a man of unimpeachable moral rectitude, but he was not simply thinking of his own career when he decided to resign. He understood that even if he were to survive, his authority was lost and he would be unable to govern. There had to be a new president and a line had to be drawn. So he became the only president in history to resign in case he was impeached, which might lead to conviction in the Senate.

Fast forward to Donald J. Trump. The 45th President, seeking a second term in the White House this November, has already been impeached twice: in 2019 for soliciting foreign interference in the then-forthcoming presidential election and subsequently obstructing the congressional inquiry into the matter; and 2021 for incitement to insurrection in an attempt to overturn the result of the 2020 presidential election. In his first Senate trial, Republican senators (with the exception of Mitt Romney of Utah) voted on straight party lines to acquit him. Romney was the first senator in US history to vote to convict a president of his own party. At Trump’s unprecedented second trial, seven Republicans broke ranks and the Senate voted 57 to 43 to convict the president of incitement, but that still fell 10 votes short of the supermajority required to remove him.

Yet none of this matters to Donald Trump. He accepts no guilt nor censure, calls 6 January 2021 “a beautiful day”, and has described those imprisoned for involvement in the insurrection as “hostages” and “patriots”. He has indicated he will pardon them if he becomes president again.

The difference between Nixon in 1974 and Trump in 2024 is simple: Nixon accepted at the very least that there was a tide of opinion that his presidency was no longer viable, even in mere anticipation of impeachment; Trump, twice impeached, simply regards it as another political battle, his enemies malign and insincere and therefore to be paid no heed. Trump knows he can rely on his party’s congressional delegation almost for anything; Nixon understood that he had forfeited the support of the GOP.

Political mores change over time, of course, and especially over a half-century. But the 50th anniversary of Nixon’s resignation shows in very obvious terms how great that change has been, and how much more politics is now a zero-sum game.

There is one ironic footnote. In the years following his presidency, Richard Nixon undertook a series of 12 interviews with broadcaster David Frost in the spring of 1977 as an attempted rehabilitation. One phrase stood out as encapsulating Nixon’s hubris: “Well, when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.” It is not a wholly inaccurate summary of the 1 July 2024 judgement of the United States Supreme Court in Trump v. United States on presidential immunity. The imperial presidency is looming in ways which Nixon could never have imagined.