The delusion of Theresa May's Downing Street

The former PM and her advisers look back ruefully on the hard times of 2016-19, but seem not to feel any personal responsibility, but all were crucially at fault

I imagine a lot of people keenly interested in politics will have watched the first episodes of State of Chaos, Laura Kuenssberg’s three-part documentary about her time as the BBC’s political editor from 2015 to 2022. The first instalment dealt with the period from the Brexit referendum in the summer of 2016 through to the early days of Boris Johnson’s premiership in the second half of 2019. It was a fascinating assembly of talking heads, including Lord McDonald of Salford, permanent secretary at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2015-20, Theresa May’s joint chiefs of staff at the Home Office and in Downing Street, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, Nigel Farage, who had led the UK Independence Party on and off between 2006 and 2016, and David Lidington, latterly May’s informal deputy from 2018 to 2019.

There has been—because there always is—fierce criticism of Kuenssberg, whom Remainers regard as a proxy for the Conservative Party and a megaphone for the propaganda of the Leave campaign, including a withering (and I would say unfair) denunciation of her performance as political editor in Byline Times by former BBC journalist Patrick Howse. I don’t want to get drawn into that controversy at this stage, nor do I want to refight the referendum or the wider argument over the UK’s membership of the European Union (full disclosure: I voted to leave, I would vote to leave again if there were another referendum, and I’ve opposed our membership for about 30 years).

I want to look at the way in which Theresa May ran Downing Street, and in particular the way she retreated into a narrow circle of (largely unelected) advisers, the effect that had on her premiership and their reflections on the period of the documentary at the distance of a few years.

Theresa May was, in many ways, notably unsuited to be prime minister. Elected to the House of Commons in 1997, she had made her name as chairman of the Conservative Party from 2002 to 2003 and had attempted to advance the so-called “detoxification” of Toryism by acknowledging its reputation as “the nasty party” at the 2002 conference in Bournemouth. In the run-up to the 2010 general election, she was shadow work and pensions secretary, having previously spoken on education and employment, transport and culture, media and sport, as well as being shadow leader of the House of Commons. When David Cameron came to construct a cabinet in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, however, several shadow ministers did not translate to their own policy fields, and May became home secretary and minister for women and equalities; the shadow home secretary, the hapless right-winger Chris Grayling, was not included in the top team. He had had a difficult election campaign, and had indicated support for bed-and-breakfast owners who refused to take gay couples as guests because of their own religious beliefs. As a result, Cameron had pointedly refused to confirm that Grayling would become home secretary in the event of a Conservative victory, and then appointed him as a minister of state at the Department for Work and Pensions, responsible for Jobcentre Plus, under Iain Duncan Smith as secretary of state.

May was only the second woman to be home secretary, after Jacqui Smith’s tenure in 2007-09, and it was a significant promotion, putting her into the front rank of cabinet ministers. She began in a relatively liberal spirit, scrapping many of the Labour government’s measures on surveillance and data collection and abolishing the national identity card scheme and its attendant database through the Identity Documents Act 2010. However, her long stint in office, just over six years, became characterised by an authoritarian spirit: she was highly critical of those who rioted in Tottenham in the summer of 2011, sought to create a “really hostile environment” for illegal immigrants, took a stringent approach to the admission of refugees and criticised the supposed laxity of the Human Rights Act 1998 in preventing deportations. She failed to tackle a backlog in processing passport applications by the Passport Office, and left a ticking time-bomb for her predecessors in her mishandling of the status of Afro-Caribbean members of the Windrush generation and their families.

When David Cameron resigned after the Brexit referendum in 2016, May emerged, to some surprise, as the leading candidate to succeed him as prime minister. She topped both ballots of MPs and was destined to face the energy minister, Andrea Leadsom, in vote of Conservative Party members. Although May had comfortably outpolled Leadsom among MPs, there was a belief that the latter, who had positioned herself as the pro-Brexit candidate of the Thatcherite right, might prove surprising popular with party members; but before the campaign could get underway in earnest, Leadsom withdrew from the race, citing lack of parliamentary support, and May was declared leader on 11 July, formally becoming prime minister two days later.

Although May set out a different stall from her predecessor, talking about those who were “just about managing”, a more responsible form of capitalism, employee representation on company boards and an explicit industrial strategy, marking herself out as being to the left of the party, there was little electric enthusiasm for her premiership. The Conservative Party was exhausted and divided after a rancorous referendum campaign, and the principal hope was that May would re-unite the party and heal its internal fractures.

There was an essential seriousness about May which could amount at times to dourness and a lack of humour. She was stiff and awkward, and although her aspirations for her premiership were inclusive, there was a moral tone about them which had been lacking in Cameron’s leadership. She was, after all, the daughter of a clergyman, the Rev. Hubert Brasier, an Anglo-Catholic who had been vicar of St Mary the Virgin in Wheatley, Oxfordshire, at the time of his death in a car accident in 1981. The year before, the young Theresa had married Philip May: she had been two years ahead of him at Oxford and was by then working for the Bank of England’s economic intelligence department while he was a graduate trainee analyst in financial services. They had been introduced at an Oxford University Conservative Association Dance by Benazir Bhutto, then a final-year PPE student at Lady Margaret Hall and later two-time prime minister of Pakistan; it is said that Malcolm Turnbull, a Rhodes Scholar reading for a Bachelor of Civil Law at Brasenose and later prime minister of Australia, had encouraged Philip to propose to his girlfriend.

May had a stable home life, then, and her husband, likewise quiet but naturally more gregarious than her, was an important source of stability and advice. Although Philip had been president of the Oxford Union, succeeding Alan Duncan and handing over to Michael Crick, and was for a time chairman of Wimbledon Conservative Association, he had decided to concentrate on his career in the City rather than pursue politics. The couple had no children, which May would later speak of with sadness. But her marriage gave her an inner strength, a steeliness which would be tested to breaking point as prime minister.

Assembling a cabinet is always a challenge, but May had to take particular care to balance Remainers, who represented most of the parliamentary party, and the insurgent Brexiteers, who had been led by Boris Johnson, former mayor of London, and Michael Gove, lord chancellor and justice secretary. Of the latter, Gove was sacked in a two-minute meeting during which May told him to “go and learn about loyalty on the backbenches”, while Johnson, improbably, became foreign secretary. There was anxiety because of his tendency to make flippant but close-to-the-knuckle remarks, especially about foreigners, but May knew what she was doing. She carved two new departments, Exiting the European Union and International Trade, out of his department, clipping his wings, and she understood that as foreign secretary he would spend a lot of time out of the country, limiting his opportunities to intrigue and organise backbenchers against her (although he had very little skill at such manoeuvres anyway).

Remainers took most of the crucial positions. Philip Hammond, an uninspiring but reliable-seeming man who had been defence secretary and foreign secretary, took over as chancellor of the Exchequer; the liberal and cheery Amber Rudd, who had been a minister for only two years, replaced May as home secretary; Michael Fallon, a veteran Thatcherite who had been a Eurosceptic but ended up on the side of Remain, stayed at the Ministry of Defence; Justine Greening, the progressive Putney MP who had just revealed she was gay, became education secretary; Jeremy Hunt, clever and deceptively well-bred but hated by the medical profession, remained in charge of the Department of Health.

The transition from the Cameron cabinet to May’s first team was described by The Daily Telegraph as a “brutal cull”, with nine ministers leaving, but what would come to matter more was that Theresa May had few close allies, let alone friends, in the parliamentary party. Damian Green, MP for Ashford, whom she had known at Oxford, became work and pensions secretary, and she had a good relationship with Hammond, her new chancellor, but May had never socialised very much in the Commons, preferring to return home to her husband. In any event, she was not an easy person to get to know, nor did she evince much desire to be better known.

The key appointment the new prime minister made was of a Downing Street chief of staff, or, rather, two: her former Home Office advisers, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, were brought back from the political dead to share the position. They were a pair who had much in common, but equally many differences; sometimes it seemed that they comprised an effective unit overall, but they would not find their time in Number 10 a happy period.

Nick Timothy was 36 when he became co-chief of staff. From a working-class family in Tile Cross in the east of Birmingham, he went from grammar school to the University of Sheffield, where he read politics, then found a job at the Conservative Research Department, joining the same month as Iain Duncan Smith was elected leader. His political hero, perhaps tellingly, was Joseph Chamberlain, the Liberal statesman who had gone from being a radical, non-conformist mayor of Birmingham to a pro-Empire, protectionist ally of Lord Salisbury’s Conservative Party. He left the CRD for two years before returning to the Tory fold in 2006 for his first stint working as chief of staff to May, at that point shadow leader of the House, then he returned to the CRD in 2008 as deputy director and remained until the general election.

At the Home Office from 2010 as one of May’s special advisers, Timothy worked on policy across the board, on police reform, criminal justice, immigration and national security. He acted as the home secretary’s representative in cross-departmental meetings, including with Downing Street and the Treasury, and helped her manage relationships with foreign governments and international institutions like the EU and UN. He also advised on media for May and the other Home Office ministers. But he was extremely combative, blunt in proposing ideas and reluctant to listen to any dissent, and was felt to isolate the home secretary from officials. He stepped down in advance of the 2015 general election and became director of the New Schools Network.

Fiona Hill was a very different proposition. She was born in Greenock and attended school in Port Glasgow, then sought a career in journalism. She initially became a football correspondent for The Daily Record, demonstrating an indefatigability as a rare woman in a male-dominated field, and then moved to The Scotsman. After a stint as news editor at Sky, she became press officer for the shadow health secretary, Andrew Lansley, and after a short period at the British Chambers of Commerce, returned to the Conservative Party in March 2009 to advise Chris Grayling as shadow home secretary.

Hill went to the Home Office principally as a media adviser at first, given her background and training. She had always been famed for her immaculate appearance—one colleague in the press remarked “she would not have looked out of place on the make-up counter in Jenners”—but she was also possessed of an explosive temper, often deployed in fanatical loyalty to her boss. Labour MP Frank Field said “People know Fiona is not someone you mess about with. She is like a good teacher in control of her class”, but others framed it more aggressively. “Puglistic” and “ferocious” were among the epithets suggested by colleagues, and comparisons to the fictional, splenetic spin doctor Malcolm Tucker were not uncommon.

In June 2014, Hill’s career hit the buffers. May was engaged in a furious row with education secretary Michael Gove over Islamic extremism in schools in Birmingham, and the home secretary wrote to Gove in strong terms accusing his department of having failed to act. Gove responded by briefing the media against the director of the Home Office’s Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism, Charles Farr, a former Secret Intelligence Service officer at that point in a relationship with Hill, who responded by leaking the letter May had written to Gove. At that point, David Cameron, the prime minister, stepped in to stop the row and re-impose discipline: Gove was forced to apologise to Farr, and May was required to dismiss Hill.

While out of office, Hill became an associate director of the Centre for Social Justice, then joined public relations stalwarts Lexington Communications as a director. But when May became prime minister in 2016, she was recalled to the colours. As had been the case at the Home Office, she dealt more with media than policy, unlike Timothy, but the pair worked hand-in-glove. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all of the problems of the Home Office, a highly centralised department which kept outsiders at arm’s length, returned. One Treasury official remarked “It says something that I don’t know anybody in her immediate circle at all”.

Timothy and Hill tightly restricted access to the new prime minister, distancing herself from her cabinet colleagues. They sat in the office outside the prime minister’s, along with their deputy, Jo Penn, the principal private secretary, civil servant Simon Case, and two diary secretaries, literally controlling access to May: cabinet ministers could not casually drop in, nor could anyone discuss ideas informally, instead having to make appointments or give submissions to Timothy and Hill, who regulated the contents of the prime minister’s red boxes.

The bearded Timothy’s influence over policy-making led to his being nicknamed “Rasputin”, while Hill, aggressive and abrasive, was thought to be a bully, openly berating members of staff, and screaming and swearing at cabinet ministers. Katie Perrior, who was serving as director of communications in Downing Street, would come to describe the chiefs of staff as “rude, childish and abusive”. After Nicky Morgan, dropped by the prime minister as education secretary, made a joke about May’s expensive leather trousers, Hill sent a text message to fellow MP Alistair Burt saying “Don't bring that woman to Downing Street again”. The Sun dubbed her “The Iron Mayden”: Hill used it as her profile picture on WhatsApp.

Some argued this tight control was an advantage, and evidence of the prime minister’s thoroughness and dedication. One colleague said:

She won’t allow herself to be bullied into making decisions that may be important to someone else but not to her. It doesn’t surprise me that people are screeching that she won’t make decisions, or she’s slow to do so. What they mean is, she won’t make the decision they want.

The truth, however, was that paperwork was building up that only May could process, and the chiefs of staff represented a bottleneck.

It was the early general election of 2017 which sealed the fate of Timothy and Hill. Theresa May is excoriated now for calling a poll only two years into a potential five-year parliament, but one has to remember the circumstances of the time. Although the constitution recognises no such thing, she was aware that she lacked a personal electoral mandate. Labour had in 2015 elected Jeremy Corbyn as its leader, to general astonishment, and as May settled into the premiership, the opposition’s popularity plummeted as everyone expected. Corbyn had scraped together the nominations of 35 fellow Members of Parliament with literally minutes to spare—when I walked past the committee room at 11.50 am for a 12 noon deadline, he had still not found enough backers—and several MPs lent their support in the mistaken belief that it would be helpful for the party to have Corbyn in the contest, to measure what most believed would be the modest support for a far-left candidate.

Theresa May was defending a slender majority of 17. Anyone who had watched the gradual disintegration of the post-1992 Major government, which began with a plurality of 21 but by the mid-1990s fell into minority status, knew that it was not a margin big enough to be a bold or dynamic administration. But the opinion polls offered an almost unbelievable prize. For the last few months of 2016, the Conservatives enjoyed a lead over Labour of between seven and 18 points, and this persisted into the spring of 2017, peaking at 25 per cent in April: that kind of margin had not been seen at a general election since the crushing victory of the National Government in 1931. If it had been translated into a result, it would have left the Labour Party probably only in double figures of seats and facing existential questions. Why would May not go for it?

Polling day brought disaster. Although the Conservatives actually won 2.3 million more votes than they had done in 2015, Labour added 3.5 million and May was left not only without a larger majority but without a majority at all. They won 317 seats; after nearly three weeks, May concluded a confidence and supply agreement with the Democratic Unionists of Northern Ireland, but even their 10 MPs only just pushed the government over the line. However persuasive her reasons for calling the election, the prime minister’s authority was in tatters, and a Conservative Home poll revealed that 60 per cent of party members thought she should resign. But she was determined to stay on. Her chiefs of staff were another matter.

Nick Timothy bore some blame for the election defeat. He had been instrumental in drafting the party’s manifesto, and in particular proposed changes to funding social care, which the opposition parties dubbed a “dementia tax”. Timothy admitted four years later that “our social care proposal blew up the manifesto”, and, while he had not been the sole author of the manifesto, it was enough for his enemies to condemn him. In fact, both he and Hill had created so much ill will in the party that MPs were ready to use the election result to dislodge them. One cabinet minister described the chiefs of staff as “monsters who propped her up and sunk our party”, and many senior figures made the equation clear: if the prime minister wanted to remain in office, Timothy and Hill were the sacrifice required. The day after the election, they resigned.

Was it fair to attach such culpability to the Downing Street chiefs of staff? After all, as they had protested and would continue to do so, they were advisers, counselling the prime minister; they were neither her jailers nor her puppet-masters. And that argument holds considerable force. On the other hand, as advisers go, they were exceptionally influential. No-one in that post except perhaps Jonathan Powell, Sir Tony Blair’s chief of staff, enjoyed such sway over the principal. Perhaps Dominic Cummings could exert similar control over Boris Johnson at times, but, while he was often described as a “de facto chief of staff”, his official title was “Chief Adviser”. So Timothy and Hill must bear more responsibility than most for decisions that May made, and, of course, Timothy was deeply implicated in parts of the election manifesto which in retrospect were judged calamitous.

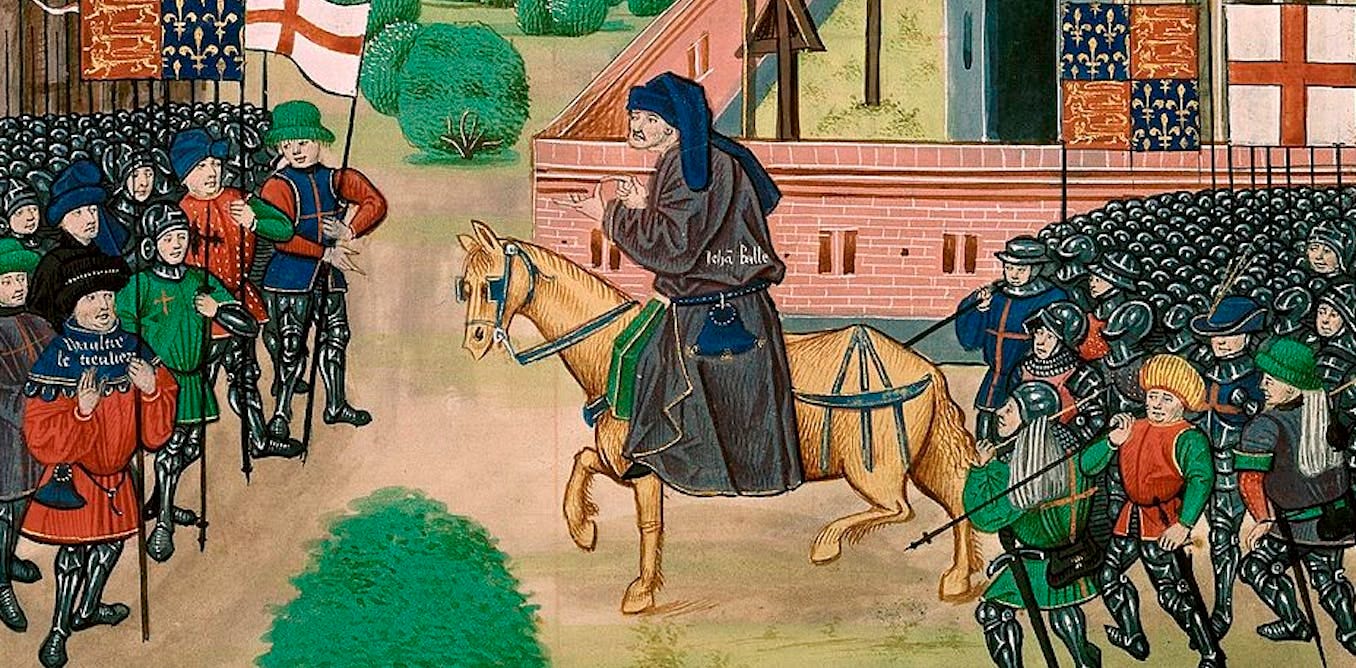

In any event, they fell pray to a very old political trope. Mediaeval and early modern England was scattered by rebellions, revolts and uprisings against royal authority which were couched in rhetorical terms of helping the king put away evil counsellors and restoring good and just governance. Those challenging authority could look back to archetypes like Unferð, the thegn of the Danish lord Hrothgar in the Old English epic poem Beowulf, who taunts the hero and sits at the king’s feet at feasts. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 saw the insurgents march under the slogan “With King Richard and the true commons of England”, and the Kentish rebels who entered London demanded the arrest of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and the king’s uncle; Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor; and Sir Robert Hales, the Lord High Treasurer. And 150 years later, in the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536-37, the framing is still the same: the rebels who spring up in Yorkshire were motivated by the ongoing dissolution of the monasteries and the apparent spread of heresy but their petition sought the removal and punishment of Thomas Cromwell, Lord Privy Seal, Principal Secretary to the King and a host of other things, and Sir Richard Rich, Speaker of the House of Commons in the Parliament of 1536 and Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations, responsible for the money flowing from the suppressed monasteries. Henry VIII, of course, remained above reproach.

So this trope came for Timothy and Hill. Conservative MPs were badly shaken by the result of the 2017 general election, and they became increasingly aware that they had not actively chosen May as prime minister. True, she was leading Andrea Leadsom on the last parliamentary ballot—though that was not much of an achievement, as Leadsom had not even been a cabinet minister when she’d emerged as a candidate—but the contest had abruptly ended with Leadsom’s withdrawal. May had enjoyed a coronation. And what did she really stand for? She had talked about David Cameron’s “true legacy” being “social justice” rather than any economic achievements, and stressed that she wanted to lead a “One Nation” government. She had launched an audit of racism in public services, pledged to “fight the injustice of being born poor” and had started talking about an “industrial strategy”, words which had been almost taboo since the days of Edward Heath. True, she had made supportive noises about the expansion of grammar schools, she had shown herself tough when it came to national security and counter-terrorism, and she kept intoning that “Brexit means Brexit”; but Conservative MPs, like everyone else, couldn’t really divine whether that slogan was deeply profound or simply nonsensical.

It was hardly surprising, then, that she was in some ways on probation from 2016, although the dizzying leads in the opinion polls soothed many critics, and some even began to see her as a second Thatcher, transforming her shortcomings of stiffness and lack of spark into positive virtues of seriousness of purpose and determination on the lines of the Iron Lady’s mythology. All of that died with the 2017 election. In Browning’s words, it would be never glad confident morning again. The weekend after the election, former chancellor George Osborne, admittedly not an impartial observer, described the prime minister as a “dead woman walking”. When Graham Brady, the veteran chairman of the 1922 Committee, had told her that Timothy and Hill must go, he had made it clear that the alternative was a leadership challenge.

To replace her fallen counsellors, May surprised many by turning to the defeated Conservative MP for Croydon Central, Gavin Barwell. He had been minister for housing and planning until the election, a pleasant and affable Cambridge graduate who had risen through local government in Croydon and the Conservative Party machine—from 2003 to 2006 he was chief operating officer, mainly under Liam Fox and Lord Saatchi’s joint chairmanship—and he was popular with MPs; accepting the position, he pledged absolute loyalty to May and would exhaust himself for the following two years attempting both to advise her and to shield her from the worst excesses of the parliamentary party.

As we all remember, Barwell’s reign as chief of staff (explained honestly and self-critically in his memoir Chief of Staff: Notes from Downing Street) was not enough to save May’s premiership. The two years between the 2017 general election and her resignation as prime minister on 24 July 2019, by when the Conservative Party had chosen Boris Johnson to replace her, were a slow, writhing death, disagreement of the form of Brexit the principal cause, but punctuated by the forced dismissal of her friend and deputy, Damian Green, in December 2017 after he lied about having pornography on his work laptop; the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Salisbury in March 2018; and the sacking of the defence secretary, Gavin Williamson, in May 2019 when an internal inquiry found that he had leaked confidential information from the National Security Council.

It was a chaotic second administration. There were 60 ministerial resignations or sackings, including 16 from cabinet, mostly over Brexit, and the strained coventions of collective responsibility and confidentiality broke down completely. Julian Smith, the government chief whip, talked about the “worst cabinet ill-discipline in history”, and by the spring of 2019, some ministerial posts were standing vacant because no MPs could be found who were willing to serve. It was a level of administrative collapse that no-one had seen before, yet it would come again for May’s successor, Boris Johnson, in the summer of 2022.

Theresa May has just published a pseudo-autobiography, The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life, and she has taken to the screens and airwaves to promote the book. Quite clearly, however, she is also engaged in a much wider, wholesale revisionism of her time in office. She recently spoke at length to former Scottish Conservative leader Baroness Davidson of Lundin Links, and the interview for Times Radio is well worth watching. But, to return to where I began, the first episode the BBC’s State of Chaos has also been very revealing.

The general attitude from May and from Timothy and Hill is to look back on the years of her premiership with a rueful regret, a degree of pain—clearly a lot still rankles—but a strange sort of detachment. They all give the impression that they were subject to some unavoidable and unforeseeable act of God. It is an abdication of responsibility on a breathtaking scale.

Now, let’s be fair. The Parliamentary Conservative Party after the 2016 referendum was almost unmanageable. While it was largely pro-Remain, and therefore on the losing side, it contained some big beasts, like Michael Gove, David Davis and, above all, Boris Johnson, who had campaigned to leave and who felt that they should be in charge of the direction of government. Agreeing the terms of a withdrawal agreement with the EU was extremely demanding, and there was no unanimity in the House of Commons about what the terms should be. Some Brexiteers were at least comfortable with, if not actively in favour of, leaving with no agreement at all, and relying on the provisions of a “hard” or “no-deal” Brexit.

May was dealt a bad hand. But it is equally clear, with the benefit of a little hindsight, that she played it with an astonishing lack of skill. As I proposed before, she was fundamentally unsuited for the premiership anyway, but especially so in the wake of the Brexit referendum. Faced with a fractious cabinet and a divided parliamentary party, she retreated to Downing Street and allowed her chief advisers to control access to her. She had never been the sort of person who had haunted the bars and restaurants of the Palace of Westminster anyway, but clearly forcing herself to act against her inclinations was not embraced as an option. For even the lowliest occupant of the office, the stardust of the premiership is a valuable commodity and can dazzle backbenchers and buy their affection at least for a time; equally, however, the inevitable ego which even the most self-effacing backbencher possesses can easily curdle into truculence and resentment if they feel ignored or taken for granted.

Appointing first David Davis, then Dominic Raab then Steve Barclay to be secretary of state for exiting the European Union was an emotionally understandable attempt to make the Leave camp “own” the process, as was sending Boris Johnson to the Foreign Office and making Liam Fox international trade secretary. But it left critical posts occupied by ministers who simply were not up to the job: Johnson was a hopeless and damaging foreign secretary, while Davis was inadequate in bargaining with the EU’s chief negotiator, former French foreign minister Michel Barnier; the difference in approach was illustrated when Barnier and his aides arrived for a meeting with thick folders of briefing material, while Davis had nothing at all, supposedly intending to demonstrate his mastery of the subject. It was hardly a surprise that progress was treacle-slow.

May was also disastrously inconsistent. Even the 2017 general election fell into this category: she had denied at least four times over the first months of her premiership that she would call an early election, then changed tack to seek a larger majority as a mandate to secure a withdrawal agreement with the European Union. The reasons why she called an early poll were understandable, as we saw above, but it seemed opportunistic and impulsive. During the election campaign itself, when criticism of the “dementia tax” started to home, she hastily sought to “clarify” the party’s position, saying that there would, after all, be a cap on costs to the individual while insisting that nothing had changed. A proposal to means-test winter fuel payments came and went within two months, as did a pledge to scrap free school lunches. The overall impression was of a leader who was not devoid of ideas, but who bent to the slightest pressure when challenged.

How could a leader with that kind of tendency possibly hope to navigate the waters of a Brexit withdrawal agreement? Any MP, from any faction, who had watched her conduct during the election campaign knew that she was likely to fold or retreat if pressed hard enough, which offered the most damaging lesson possible to her opponents. Moreover the parliamentary party had people in it who were ruthless and so committed to the their causes that the possibility of the government collapsing was not the worst possible outcome. Even the presence of Jeremy Corbyn, an unthinkable occupant of Downing Street for anyone on the right, was not enough to make Conservative MPs stop and think that unity had at least some place in their priorities.

Anyone hoping to lead the Conservative Party after the referendum had to be an exceptional communicator, possessed of outstanding interpersonal skills, combine strategic resolution with tactical flexibility and a sixth sense for what was politically possible, and, ideally, have a coherent set of ideas for the future of the country which absorbed the new fact of Brexit. Theresa May was literally none of these things. And before we feel too much sympathy, remember that very few prime ministers are pressed men (or women). She wanted the job and offered herself for it. She was not the first to do so—that distinction went to Stephen Crabb, the work and pensions secretary, running on a joint ticket with Sajid Javid—but she was not bounced into it: she stood as a candidate to unify the party, appointing Brexiteer Chris Grayling as her campaign manager to woo the right-wing vote, and was the bookies’ favourite as soon as she launched her campaign. And she was dismissive of criticism that she was a low-profile minister.

I don’t gossip about people over lunch. I don’t go drinking in parliament’s bars. I don’t often wear my heart on my sleeve. I just get on with the job in front of me.

But it seems that for May there is always someone else at fault. Andrew Rawnsley, reviewing The Abuse of Power for The Observer, notes that, when it comes to getting a withdrawal agreement through the House of Commons, she “presents herself as a woman piously motivated by wanting to do the right thing who was unreasonably thwarted by almost everyone else, including EU leaders, the Labour party and speaker John Bercow”. And of course the task was made a dozen times more difficult by the government’s lack of a majority, the result of an election she had decided to call. Her interpretation, and the reason she includes the sorry tale of the search for a Brexit agreement in a book about abuses of power, is that her opponents worked in their own factional, personal interests, while she merely sought what was best for the country. As Rawnsley concludes with audible distaste, “that suggestion is not just ridiculous, it is repulsive”.

Nor can Timothy escape responsibility. He, for example, was instrumental in drafting May’s January 2017 speech at Lancaster House, in which the prime minister set out her Plan for Britain, including the 12 guiding principles which would inform her negotiations with the EU. One so-called “red line” was withdrawal from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, an idea inserted by Timothy, and one which made it inevitable, if it had not already been so, that the UK would not remain in the Single Market. After his departure in June 2017, he continued to contribute from the sidelines, in ways which were not obviously helpful, condemning the government’s negotiating stance and telling the prime minister to toughen up and take drastic action. When Laura Kuennsberg made a documentary called The Brexit Storm in 2019, Timothy was on hand to tell her that Theresa May regarded Brexit as a “damage limitation exercise”, adding “If you see it in that way then inevitably you’re not going to be prepared to take the steps that would enable you to fully realise the economic opportunities of leaving”.

I suspect Theresa May has been emboldened by the catalogue of catastrophes which has followed her, from the most egregious offences of Boris Johnson’s premiership to its ignominious and slow dissolution, followed by the tragi-comedy of Liz Truss’s 49 days in Downing Street. Unusually for a former prime minister, she has remained in the House of Commons (Blair and Cameron departed instantly, Brown was not much seen) and has developed a strange, amnesiac cult following which holds up her self-professed dedication to duty as a fun-house mirror to Johnson’s rampant egotism and self-regard. Her new book is clearly a continuation of a theme.

In the end, though, while reflecting that the period from 2016 to 2019 was a very tough one for British politics in general and the Conservative Party in particular, it is difficult to avoid to conclusion that Theresa May and her court made it even worse than it could have been. She was the wrong person to lead, and almost every decision was wrong. Yet now they look back and think how sad it was, how tragic but noble, that they faced such terrible challenges. The public must remember that many of them were of their own making.