The Conservatives and Reform UK: future partners? Lessons from history

It has been proposed that the two parties will eventually merge, but what can previous mergers of political organisations tell us? Here are some examples

It is inevitable, but slightly mad, that more than a week before polling day we are spending quite so much time and effort wargaming the future of the Conservative Party after 4 July (if, with an eye on some of the lip-smacking doom-mongers, it has one at all). Still, we are where we are. One of the scenarios being rehearsed is that the Conservatives will be reduced to a tiny parliamentary rump, perhaps fewer than 100 MPs, and they will be the target of a hostile takeover by Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, riding a wave of populist sentiment and dissatisfaction with the established political system.

The details of this turn of events are vague, of course, because anyone making predictions is taking several steps into the future, each dependent on the previous, with the attendant possibility of steering far off course. For what it’s worth, I don’t think this will come to pass, for several reasons: I don’t think the election will be quite as catastrophic for the Conservative Party (though the result will clearly not be good), I don’t think Reform UK will poll as strongly as some people suggest, I don’t think Farage has the skills required to pull off such a daring and delicate act of political prestidigitation, and I don’t think either party would be as enthusiastic as suggested about a process which would clearly be the creation of yet another vehicle for the career of Nigel Farage. Of course, I may be wrong on some or all of those points, and we will know soon enough. But I thought it might be worth looking at the past to see how the mergers of political parties work.

It is a striking feature of British politics that our established parties are both adaptable and durable. I wrote about this earlier in the year, but it bears repeating that, with a generous classification, you can trace the Conservative Party all the way back to the Exclusion Crisis of 1679, while the Liberal Democrats, in a convoluted way, can claim descent from the Whigs who emerged at the same time. The Labour Party was founded in 1900, but the first “Liberal-Labour” parliamentary candidate stood in 1870 and the Independent Labour Party, which would eventually fold itself into the Labour Party in 1975, was founded in 1893. In all that time, the only serious realignment of parties, despite a number of false dawns, has been the replacement of the Liberal Party as one of the two mainstream parties of government by Labour, which took place in parliamentary terms at the 1922 general election: Labour won 142 seats while H.H. Asquith’s Liberal Party won 62 and David Lloyd George’s short-lived National Liberal Party won 53.

We are not unique in this. The United States has alternated between the same two parties since 1864, when Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, was re-elected against the Democratic candidate General George McClellan. Some countries, however, have much more fissiparous ideological groups. If, for example, you look at the leading parties in the last French legislative elections in 2022, then at the elections only 15 years before, in 2007, you will find hardly any parties with an unchanged identity: essentially only the Socialist Party, the Citizen and Republican Movement, the French Communist Party and the New Centrists. In Germany, a sort of halfway house, the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party endure from the immediate post-war period; but Alliance 90/The Greens have elbowed their way to a party of government, first taking office at the federal level in 1998, the Free Democrats disappeared from the Bundestag in 2013 but have rallied somewhat, and Alternative for Germany burst into parliamentary representation in 2017, winning 93 seats from a standing start.

Despite Britain’s resilient party structures, there have been comings and goings, groups which have emerged, found a niche in the ecosystem for a while and then merged with or been absorbed by one of the established parties.

The Liberal Unionists

In 1885, William Gladstone, the 75-year-old Liberal leader who had resigned as prime minister that summer, came to the conclusion that the only solution to what was known as “the Irish Question” was home rule, the creation of a devolved parliament for Ireland to take on most areas of domestic policy. The immediate political effect was seismic: the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party, led by Charles Parnell, whose 85 MPs held the balance of power in the House of Commons, joined with the Liberal Party to defeat the minority Conservative government led by the Marquess of Salisbury. After only a few months in opposition, Gladstone became prime minister for the third time in February 1886 and prepared to introduce a bill to deliver home rule.

Gladstone’s conversion had not been universally welcomed in his own party, however. Many of his colleagues, especially the more Whiggish and aristocratic faction of the Liberals, feared that home rule would lead to independence for Ireland and the dissolution of the United Kingdom. Some also had a personal stake in the issue, owning large estates in Ireland which they feared would be broken up or confiscated by a Dublin government.

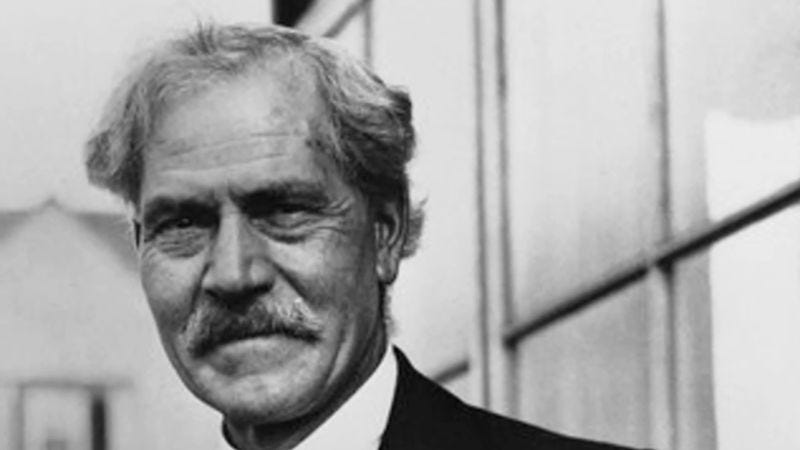

Most prominent among them was Lord Hartington, former secretary of state for war and heir to the Duke of Devonshire; his younger brother, Lord Frederick Cavendish, had been assassinated by militant Irish nationalists in Phoenix Park in Dublin in 1882 on his first day as chief secretary for Ireland, the cabinet minister with day-to-day control over the Dublin Castle administration. Other dissenters included the Marquess of Lansdowne, scion of the Protestant Ascendancy and at that point serving as governor general of Canada, and George Goschen, a banker of German descent who had declined office in Gladstone’s 1880 government as well as turning down the post of viceroy of India. They rapidly formed a Committee for the Preservation of the Union, and, to general surprise, were soon joined by two figures from the Liberal Party’s radical tradition, Joseph Chamberlain and John Bright. Chamberlain, who had been president of the Board of Trade from 1880 to 1885, had become a somewhat unlikely imperialist, while Bright distrusted the Irish Parliamentary Party as rebels and, as a Dissenter, stood for the defence of the Protestant minority in Ireland.

In April 1886, Gladstone introduced the Government of Ireland Bill which made provision for home rule. Parnell thought the legislation flawed but was willing to support it, but when the House of Commons came to vote on its Second Reading on 7 June, 92 Liberal MPs joined the Conservatives in the opposition lobby and the bill was defeated by 341 votes to 311. Gladstone inevitably resigned and Parliament was dissolved on 26 June. At the following month’s general election, Liberals who opposed home rule stood as “Liberal Unionists”, and 77 of them were elected. Salisbury’s Conservatives won 316 seats, 20 short of an overall majority, but Hartington and the Liberal Unionists, although they continued to sit on the opposition benches, agreed to support the Conservative government.

If there was still at that point some notion that the Liberal Unionists might rejoin their former colleagues, it quickly drained away. When Lord Randolph Churchill resigned as chancellor of the Exchequer in December 1886 over potential cuts to the Royal Navy and Army, Salisbury appointed Goschen, a Liberal Unionist, who, with Hartington’s blessing, accepted the office and held it for another six years. An attempt to heal the Liberal schism in 1887 failed, and the Liberal Unionists again combined with the Conservatives in 1893 to vote against another Government of Ireland Bill. While it was passed by the House of Commons, Liberal Unionist peers led by the Duke of Devonshire (as Hartington had become in 1891) helped defeat it at Second Reading in the House of Lords by the overwhelming margin of 419 to 41.

At the general election of 1895, the Liberals, now led by the Earl of Rosebery, were reduced to 177 MPs. The Conservatives won 340 seats with the Liberal Unionists taking 71, and when Salisbury formed his third ministry it was an overt Conservative/Liberal Unionist coalition: Devonshire became lord president of the Council, Lansdowne was appointed to the War Office, Chamberlain became colonial secretary and Lord James of Hereford, a former attorney general, became chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Tension remained within the Liberal Unionists between conservative Whigs and radical Chamberlainites, but the lure of office kept both wings of the party, as well as the two coalition partners, together.

The momentum was irresistible towards unification. After the electoral disaster of 1906, the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists might have become divided over the personality of the leadership, as Chamberlain, a more combative and dynamic figure than A.J. Balfour, who had succeed his uncle Salisbury as Conservative leader, could plausibly have claimed pre-eminence in the coalition. But in July 1906 Chamberlain, five days after his 70th birthday, suffered a severe stroke which left him paralysed down his right side. Although he made a modest physical recovery, and remained mentally unimpaired, the future was obvious. In May 1912, the two groups united as the Conservative and Unionist Party, known informally until the mid-1920s simply as Unionists.

How should we judge this merger? The Liberal Unionists were obviously the smaller and less wealthy partner, and they had lost their two greatest figures: Chamberlain lived on until July 1914 but never recovered his physical abilities, while Devonshire had died in 1908. Lansdowne had led the party in the Lords since 1903 but by the time of the merger he was 67 years old. Goschen had died in 1907, James of Hereford in 1911, and Alfred Lyttelton, who had succeeded Chamberlain as colonial secretary, would die in 1913. The only major figure left by 1912 was Chamberlain’s eldest son Austen, 48 years old and a former chancellor of the Exchequer: when Balfour resigned as Conservative leader in November 1911, Chamberlain was a potential successor, although a Liberal Unionist, and Balfour favoured his candidacy, but it was clear that the parliamentary party (or parties) was split between him and Walter Long, leader of the Irish Unionists and a rural conservative. Eventually both stood aside to allow Andrew Bonar Law, the abrasive Glasgow ironmaster now sitting for Bootle since losing his Dulwich constituency, to take over.

In policy terms, by 1912 the Liberal Unionists, like the Conservatives, had settled for a platform of protectionism (or “tariff reform”). The Irish question would continue to bind the new party under a Unionist banner until the Government of Ireland Act 1920, the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and the establishment of the Irish Free State in December 1922. An argument has been made that fusion of the Conservatives and the Liberal Unionists, and the influence of the Chamberlain family on the latter, maintained Conservative fortunes in Birmingham long after demographics would have suggested a change of allegiance. It is certainly striking that at the 1935 general election, all 12 Birmingham MPs were Conservative, while, of the 13 seats contested at the 1945 election, 10 fell to the Labour Party.

Overall, however, except for the mechanics of parliamentary arithmetic, would the history of the Conservative Party have been very different without its alliance with Liberal Unionism? That is a tougher case to make. On the other hand, the departure of the Unionist faction probably did make a significant difference to the Liberal Party it left behind. From its formal establishment in 1859, the Liberal Party was an uneasy coalition of the elements from which it had been created: aristocratic but reformist-minded Whigs, Radicals who championed free trade and many of whom were Nonconformists, and the remaining Peelites who had broken with the Conservatives over free trade. It remained a broad but sometimes quarrelsome church for decades, and the schism over home rule in 1886 was a case of an inevitable outcome but a coincidental cause.

In a strange way, the establishment of the Liberal Unionists cleansed and unified the Liberal Party in ideological terms, even if it did condemn it to opposition for more than 16 of the following 20 years. With the departure of the Radicals like Chamberlain and Bright, and the great Whig landowners like Devonshire and Lansdowne, the Liberals wholeheartedly embraced social and educational reform and for a while offered the most obvious ally for the nascent trades unions. Divisions would resurface, between imperialists and anti-militarists, between supporters and opponents of women’s suffrage, between all-but-socialists and classical liberals, but these would not prevent the party winning a landslide victory at the 1906 general election, and the Liberals had, to use Lynton Crosby’s phrase, cleaned the barnacles off the boat.

For the Liberal Unionists themselves, however, they essentially undertook a 25-year journey from being a faction of one major party to being a faction of the other. They were an important element in the changing political landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries but left very little trace of themselves behind; few outside the community of political historians remember them today. “Radical Joe” Chamberlain survives as the Birmingham colossus with a monocle and an orchid in his buttonhole, and Devonshire is sometimes cited as probably the only man who three times declined the opportunity to become prime minister (in 1880, 1886 and 1887). But the party is a niche interest. Indeed, how many people now are aware that the Conservative Party’s formal title includes the words “and Unionist”?

The Independent Labour Party

Relatively speaking, it is common currency that Keir Hardie led the foundation of the modern Labour Party in 1900, a fact given contemporary piquancy with the likely impending accession of Sir Keir Starmer as prime minister. (Starmer was reputedly named for his predecessor though he claims not to know if that story is wholly true; there are two other Labour candidates in this election bearing that name, Keir Mather in Selby and Keir Cozens in Great Yarmouth.) However, we tend to overlook the earlier establishment of a similar body which was outstripped by Labour.

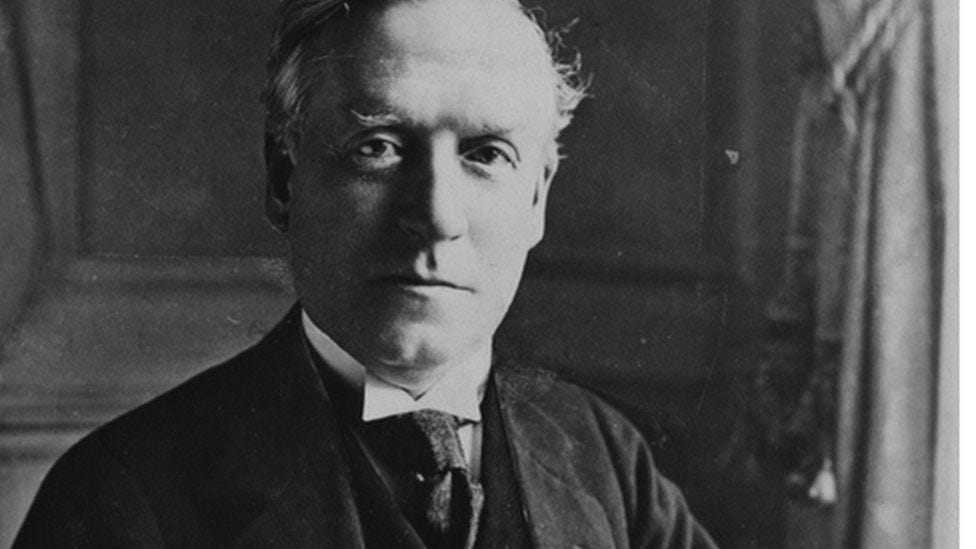

The Independent Labour Party was founded in Bradford in January 1893 by delegates from across the socialist spectrum, from author George Bernard Shaw to trades union leader Ben Tillett. It grew out of a dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party’s representation of working-class issues, and the first chairman was the “independent Labour” MP for West Ham South, 46-year-old former miner Keir Hardie. It adopted a radical socialist platform including collective and communal ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, free, non-denominational education, the abolition of child labour, a minimum wage and an eight-hour working day. Addressing the new party’s conference, Hardie argued that the ILP was not an organisation, but “the expression of a great principle”. He foresaw it as a federation of local parties bound together at the national level only “to such central and general principles as were indispensable to the progress of the movement”.

Despite its grand, almost utopian vision, the ILP did not prosper in its early years. Hardie was defeated at the 1895 general election, as were the party’s 27 other candidates, and that made it wary of overstretching its resources by contesting too many seats. In February 1900, the Trade Union Congress assembled the broadest possible range of left-wing and socialist organisations to try to co-ordinate political activities and sponsor parliamentary candidates, and the Labour Representation Committee—generally regarded as the forerunner of the modern Labour Party—was born. It comprised two nominees from the ILP, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one from the Fabian Society and seven trades union delegates. In keeping with the egalitarian spirit of the organisation, there was no designated leader, but Ramsay MacDonald, one of the ILP representatives, was elected as secretary. At the general election later that year, which the Conservatives and their Liberal Unionist partners won with a majority of 134, the ILP only fielded nine candidates (of the LRC’s total of 15) but Hardie returned to the House of Commons as MP for Merthyr Tydfil.

The ILP improved its tally in 1906, with seven of its 11 candidates being elected, along with another 22 under the LRC banner. Immediately after the election, the leadership of the LRC decided to adopt a more efficient and formalised political structure, and adopted the title of the Labour Party; there would be no de jure leader until 1922, but Hardie was elected chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party and effectively head of the revamped organisation. It remained, however, a federation of allied bodies, and the ILP maintained its existence as an affiliated member, as well as providing much of its early activist base, continuing to hold its own conferences and agree its own policy platforms. It had an aspirational, visionary air about it that some compared to a sort of secular religion. Fenner Brockway, who would go on to chair the party in the 1930s, said of a meeting in 1907:

On Sunday nights a meeting was conducted rather on the lines of the Labour Church Movement—we had a small voluntary orchestra, sang Labour songs and the speeches were mostly Socialist evangelism, emotion in denunciation of injustice, visionary in their anticipation of a new society.

In those early days, many of the leading figures in the Labour Party were drawn from the ILP: Hardie and MacDonald, of course, but also J.R. Clynes, Clement Attlee, George Lansbury, John Wheatley and Josiah Wedgwood. Emmeline and Sylvia Pankhurst were members at one point, as later was George Orwell. When Labour formed its first government in January 1924, nearly a third of the cabinet came from the ILP: MacDonald, Snowden, Jowett, Wheatley, Wedgwood, Trevelyan.

As the 1920s wore on, however, there was an increasing gap opening between the ILP and the rest of the Labour Party. MacDonald was ousted as editor of the ILP’s Socialist Review in 1925, and Snowden left the party in 1927. The following year, after what many members felt had been the disappointment of the first Labour government, the ILP produced a new platform called “Socialism in Our Time”: it included wide-ranging nationalisation, a living wage, the bulk purchase of food and raw materials and a substantially increased unemployment allowance. MacDonald and the other leaders of the Labour Party were hostile to an approach which was so different from his own gradualist notion of socialist progress; although 37 ILP Members of Parliament were returned at the 1929 general election, when MacDonald formed a second Labour government, none was appointed to the cabinet this time.

A parting of the ways was almost inevitable. At its conference in the first months of 1931, the ILP debated disaffiliating from the Labour Party, and delegates were only persuaded to remain within the movement by the intervention of the chairman, the charismatic Glasgow Bridgeton MP James Maxton. That summer, however, the Labour Party split when MacDonald formed a “National” coalition government with the Conservatives, Liberals and the Liberal National Party. Labour expelled MacDonald, its leader, and the other senior ministers who supported the new government. At the subsequent election in October, the ILP rejected new standing orders introduced by the Labour Party and decided not to stand under the Labour banner. Twenty-five ILP candidates were nominated, and a mere six were returned: George Buchanan, David Kirkwood, James Maxton, John McGovern, R.C. Wallhead and Josiah Wedgwood. It is worth noting that four sat for Scottish constituencies, one for Hardie’s old seat of Merthyr and only one for an English division.

This small band sat separately from the Labour Party in the House of Commons, and in 1932 a special party conference finally voted to disaffiliate from Labour. Aneurin Bevan was probably right when he described the decision as a desire to remain “pure, but impotent”. Certainly the ILP was finished as a political force. By 1935, it had lost three-quarters of its membership and was reduced to just 4,392. A request in 1939 to re-affiliate to the Labour Party, while retaining the right to propose independent policies, was predictably rejected, and at the 1945 general election it won only three seats, all in Glasgow. In July 1946, Maxton, easily the ILP’s biggest remaining figure, died, and his successor, James Carmichael, along with his two remaining colleagues, Campbell Stephen and John McGovern, defected to the Labour Party in the course of 1947.

The ILP survived as an extra-parliamentary group, taking an early anti-nuclear stance and campaigning for decolonisation. In 1975, however, the party bowed to the inevitable. Under its last chairman, Stan Iveson, it ceased to be a political party and transformed itself into Independent Labour Publications, a campaigning group within the Labour Party. Its full members are now prohibited from standing for elected office.

What can the fate of the ILP tell us? In its early days it not only provided much of the activist base of the nascent Labour movement but also an evangelical and attractive form of socialism which took hold with surprising speed in a well-entrenched two-party political system. Bear in mind that the Labour Representation Committee won two seats at its first general election in 1900, and by 1922 had supplanted the fractured Liberals as one of the two main parties, a position it has never ceded. Like many progressive organisation, however, it never fully resolved the internal tension between ideological purity and the messy compromises of office. It lost many MPs, members and supporters by adhering to its strict pacifism in 1914 and opposing the United Kingdom’s participation in the First World War, which an influx of formerly Liberal intellectual figures like E.D. Morel, Charles Trevelyan and C.R. Buxton could not mitigate.

The history of the ILP in the 1920s, however, is instructive. In essence, the leading figures of the Labour movement like Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson and J.R. Clynes (three of whom were one-time ILP members) took a decision to participate in the parliamentary process and to take ministerial office when the opportunity arose. They did so in the knowledge that compromise was thereby inevitable, and that socialism would not be implemented overnight. Those who continued to adhere to the ILP during the 1920s and afterwards were not willing to make that accommodation with quotidian politics. You can take your own view on who made the correct decision, but, in June 2024, we are anticipating a landslide general election victory for the Labour Party, while the ILP ceased to exist as a party nearly 50 years ago.

The road to the Liberal Democrats

While the Liberal Party ceased to be a serious contender for government in 1922, a desire has persisted among enough people for a “centre party” or “third force” to stop the United Kingdom becoming as binary as, say, the United States. The Liberals took a long time to settle into their place as a minority party; when H.H. Asquith, having reunited the party after its wartime schism, agreed to support the minority Labour government in January 1924 on an ad hoc basis, he did so in the expectation that it would fail sufficiently badly that socialism would be discredited and the Liberal Party would resume its position as the main centre-left group in British politics.

It was not prima facie an absurd proposition at that stage. While the Conservatives were the largest party in the House of Commons with 258 seats, the new Labour administration had only 191 MPs, while the Liberals were not so very far behind with 158. The party had united around free trade as Stanley Baldwin had converted the Conservatives to protectionism, and Asquith could point to its progressive credentials in creating the foundations of the welfare state: the Education (Provision of Meals) Act 1906, the Old Age Pensions Act 1908, the Labour Exchanges Act 1909, the Housing, Town Planning, etc. Act 1909 and the National Insurance Act 1911, among others. In addition, less than a decade after the Russian Revolution and the wave of left-wing uprisings across Europe, there was still considerable unease at the idea of a socialist government.

It was, however, an illusion. Asquith was 71 years old, and although his spirits had been buoyed when he had unexpectedly won a by-election in Paisley in 1920 after losing his seat at the previous general election, it was not an indicator of a wider trend. He had financial worries and was drinking heavily, and was widely criticised for allowing the Labour Party to take office. Moreover the Liberals’ demographic base was no longer there: the growth in the Labour vote from 2.2 million in 1918 to 4.1 million in 1922 to 4.3 million in 1923 showed which way the wind was blowing, and the electoral system exacerbated the Liberals’ plight.

The 1945 general election confirmed the Liberal Party’s place as a minor party. It won only nine per cent of the vote, returned 12 MPs in a House of Commons of 640, and its leader, Sir Archibald Sinclair, lost his Caithness and Sutherland seat. During the 1950s, support dropped below three per cent, and even the so-called “Liberal revival” of the early 1960s saw the party peak at 11 per cent and 12 MPs. Jeremy Thorpe, leader from 1967 to 1976, took the Liberals to nearly 20 per cent in the two elections of 1974, but by the time Margaret Thatcher entered Downing Street in 1979, they had slipped back to 13.8 per cent and 11 MPs. It hardly helped that Thorpe had been committed for trial at the Old Bailey on charges of conspiracy and incitement to murder a few months before.

In 1980 and early 1981, a number of events took place which revitalised the idea of a centre party. In June 1980, Roy Jenkins, the Labour grandee who had left British politics to become president of the European Commission in January 1977, gave a speech to the Parliamentary Press Gallery in which he denounced the two-party system and the left/right paradigm, as well as condemning the Labour Party’s tacking to the left. At its annual conference in Blackpool in September, Labour adopted a policy platform which included unilateral nuclear disarmament, withdrawal from the European Economic Community and widespread nationalisation. Two months later, James Callaghan resigned as leader and was succeeded by veteran left-winger Michael Foot, who beat heavyweight former chancellor Denis Healey by 139 votes to 129.

What had been simmering discontent among right-wing Labour MPs burst into the open on 25 January 1981. David Owen, Shirley Williams and Bill Rodgers, who had all been in the last Labour cabinet, were joined by Jenkins and issued the Limehouse Declaration, a statement which condemned the ideological declaration of Labour and announced their intention to leave the party to form the Council for Social Democracy. They were dubbed the “Gang of Four”, and a week later published a list of supporters which included 13 former Labour MPs. By March they had formed the Social Democratic Party (SDP), and would eventually attract 28 Labour MPs and one Conservative. Williams (Crosby) and Jenkins (Glasgow Hillhead) rapidly returned to the House of Commons at by-elections.

The SDP was obviously in the same political space as the Liberal Party and the two co-operated from an early stage. In June 1981 they formed the SDP-Liberal Alliance under the joint leadership of Jenkins and Liberal leader David Steel, which would see them stand one candidate in each constituency and offer themselves at the next general election as a potential coalition government. The Alliance soared in the polls as the Conservative government went through grim economic reforms, briefly exceeding 50 per cent at the end of 1981, but when the election came in June 1983, the first-past-the-post electoral system was its undoing. It won 25 per cent of the vote, only three points behind Labour, and amassed 7,780,949 to Labour’s 8,456,934, but the results at a parliamentary level were dramatically different: Labour was reduced to 209 seats but the Alliance won only 23 (17 Liberal and six SDP), and Williams and Rodgers were defeated.

David Owen replaced Roy Jenkins as leader of the SDP, and was warier of his Liberal partners. Proposals for a formal merger between the parties were smothered at the SDP’s annual conference, but the Alliance was maintained for the 1987 general election. It was no more successful: 23 per cent and 7,341,633 votes only gave them 22 MPs as Jenkins was defeated in Glasgow. Steel revived the idea of a merger, and was supported by Jenkins, Williams and Rodgers, while Owen was vehemently against the idea and resigned the leadership of the SDP in August. The memberships of both parties were in favour, and in March 1988 the two organisations came together as the Social and Liberal Democrats (SLD), while Owen and two colleagues, John Cartwright and Rosie Barnes, formed a “continuing” SDP. It declined until Owen wound it up after the SDP candidate finished behind the Official Monster Raving Loony Party in the Bootle by-election in May 1990.

Steel and former Labour and SDP MP Robert Maclennan served as interim leaders of the SLD, but in July the former Liberal Yeovil MP, Paddy Ashdown, was elected to head the new party, comprehensively beating fellow former Liberal Alan Beith. In September the SLD adopted the shorthand name “the Democrats”, before settling on “Liberal Democrats” in October 1989 and adopting the current logo of the bird of liberty. Ashdown would lead the party for a decade, and in 2010 they would (re)enter government as part of a coalition with the Conservative Party.

If one discounts the Owenite rump, the SDP had lasted for not much more than seven years. Its legacy remains controversial: Owen came to the view that it had been Jenkins’s intention to join the Liberals all along, while he wanted to maintain a distinct, European-style social democratic identity, and he felt that had undermined the SDP from the beginning. Jenkins, true enough, had considered joining the Liberal Party in 1979, but Steel had persuaded him that he would be more effective creating a breakaway force from Labour and co-operating with the Liberals. But he blamed the demise of the SDP on Owen’s intransigence and ambition. Nevertheless, it is hard to deny that Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, as he became, biographer of Gladstone and Asquith, friend of Mark Bonham Carter, his sister Laura and her husband Jo Grimond, Liberal leader from 1956 to 1967, seemed very much at ease when he led the Liberal Democrat peers from 1988 to 1997.

Are the Liberal Democrats a true merger? For many years, there certainly seemed to be a degree of internal ideological tension which suggested the melding of two different traditions. Although Jo Grimond had repositioned the Liberals as a radical non-socialist alternative, the injection of social democratic DNA pushed the Liberal Democrats more towards public spending, progressive taxation and a mixed economy, marginalising many of the tenets of classical liberalism (some of which, perhaps unexpectedly, would be taken up by Thatcherite Conservatives). The modern party owes some intellectual foundations to Leonard Hobhouse, whose 1911 volume Liberalism shares many values with Anthony Crosland’s seminal The Future of Socialism (1956). It has tended to be dominated by politicians who are sympathetic to social democracy, and two of its leaders, Charles Kennedy (1999-2006) and Dr Vincent Cable (2017-19), had been members of the SDP. The opposite tendency was encapsulated by The Orange Book: Reclaiming Liberalism, a 2004 volume which advocated personal choice and liberty and was open to market solutions which embraced choice and competition.

Ashdown had maintained a stance of so-called “equidistance” between the two main parties, arguing that the Liberal Democrats should seek to replace Labour as the progressive alternative to the Conservatives but without embracing socialism. This always felt somewhat forced, and there was always an assumption that, if forced to choose, the Liberal Democrats would prefer to work with Labour. Equidistance was abandoned in 1995, and after the Labour victory of 1997 there were tantalising hints of co-operation. Tony Blair’s enormous majority of 179 meant he had no need to seek the help of the Liberal Democrats, even though they had grown from 18 MPs to 46, but Blair, never truly a tribal politician, was still interested in working with Ashdown. He had even considered the possibility of a coalition government, but backed down for fear of alienating his cabinet.

In July 1997, however, Blair created a cabinet committee on constitutional reform, inviting Ashdown and other senior Liberal Democrats to participate. He then asked Jenkins, whom he regarded as a mentor, to chair an independent commission on the voting system, which reported in September 1998. Later, in 2007, Gordon Brown would offer Ashdown the post of Northern Ireland secretary in his first cabinet. Yet the great irony is that it would be in partnership with the Conservatives that the Liberal Democrats would finally enter government in 2010. As I wrote in March, that irony was sharpened by the fact that the experience of coalition government almost destroyed the Liberal Democrats.

The fundamental question, however, is whether an ongoing Liberal Party could have achieved most of what the Liberal Democrats have done, or whether the merger with the SDP was critical to their future. In parliamentary terms, the SDP-Liberal Alliance does seem to have provided a modest boost: the Liberals had 11 MPs in 1979 but grew to 17 in 1983 and 1987. That said, they had won 14 seats in February 1974 and 13 in October. Although the SDP would peak at 28 seats in the 1979-83 Parliament, it would only win six seats in 1983 and five in 1987. At the new party’s first general election in 1992, 20 Liberal Democrat MPs were elected, then the contingent would grow substantially: 46 in 1997, 52 in 2001, 62 in 2005 and 57 in 2010.

It is hard to argue that this owed a great deal to the SDP. The Liberals outpolled the SDP at the elections of 1983 (4,273,146 v 3,507,803) and 1987 (4,170,849 v 3,168,183), and the Liberal Democrats would win 5,999,606 in 1992. Was that unachievable as a single party? Perhaps the shock of the SDP’s creation in 1981 focused public attention on the idea of a “third force” in British politics, but there had been much-vaunted “Liberal revivals” under Grimond and Thorpe, so the notion was hardly revolutionary. Equally, the Labour Party did itself much harm with its leftward lurch culminating in Foot’s election as leader in 1980, and the Liberal Party alone would have benefited from that to an extent.

The SDP did provide a pathway for many significant political figures to the eventual destination of the Liberal Democrats. As mentioned above, Kennedy and Cable, both party leaders, had been in the SDP. Apart from Jenkins, Lord Rodgers of Quarry Bank would lead the party in the House of Lords from 1997 to 2001, succeeded by Lady Williams of Crosby from 2001 to 2004 then Lord McNally from 2004 to 2013. Robert Maclennan served as president of the Liberal Democrats from 1994 to 1998, while Chris Huhne would speak on home affairs 2007-10 before sitting in the coalition cabinet from 2010 to 2012. Mark Oaten was party chair 2001-03 and would contest the leadership in 2006, and Sir Robert Smith was a senior whip throughout the 2000s.

Strangely, it is perhaps easier to argue that the SDP was a significant influence on the Labour Party. Not only did the departure of many right-wing Labour MPs, including some senior and very able figures, push the party to an election loss which shocked many members into reaction; one can see shades of the SDP in New Labour, with a less tightly bound relationship with the trades unions, a greater openness to the free market and an enthusiasm for constitutional reform. Jenkins, as mentioned, became a mentor to Tony Blair, and the Labour leader made overtures to Owen in 1996, though Blair’s support for the European single currency was an insuperable obstacle. Other former SDP members who returned to New Labour included Andrew Adonis, Lord Young of Dartington, Lord Sainsbury of Turville, Lord Liddle and Lord Mitchell.

The SDP itself, of course, was essentially wiped from the political scene. It perhaps acted as a spur to change in other parties, albeit in a modest way. But, like the Liberal Unionists before it, its presence has vanished into the world of political science and history.

Conclusion

I’m an historian by training and inclination, and I think the study of history is vastly important in helping us understand our present better and more deeply. I wrote about the use of history recently in the context of right-wing thinkers, and earlier in the year more generally. The past gives us important context but it cannot tell us everything about the future: to an extent, we have to echo my hero F.E. Smith when a judge told him that he had listened to his submission for an hour but was none the wiser. “None the wiser, perhaps, my lord, but certainly better informed.” To put it another way, as Rory Sutherland says, “It’s important to remember that big data all comes from the same place—the past”.

I say this because it means that the future of the Conservative Party, and especially its relationship with Reform UK, is not pre-determined by political history, but we can look to the past for clues, for indications of what might happen. If two of my central predictions are roughly accurate, that the Conservatives will be defeated but will not wiped out and that Reform will only win a handful of seats in the House of Commons, then I would argue on that basis that Reform’s future is relatively limited.

If we imagine, for example, a merger between the two parties, then precedent points to the smaller, younger party effectively being absorbed and gradually forgotten, as the Liberal Unionists and the SDP were, as well as much of the ILP. In electoral and parliamentary terms, the Conservatives would more or less swallow up Reform’s support and revitalise themselves.

That said, looking at the past could suggest that, even if Reform were institutionally absorbed, it might have an influence on the Conservatives in terms of personnel and ideology: look how many senior Liberal Democrats had roots in the SDP, or Conservatives in the Liberal Unionists. However, Reform is, to put it mildly, not overcrowded with major figures: as its entry at Companies House demonstrates, it is little more than a vehicle for Nigel Farage’s continuing political career, and it currently has no formal structures or internal democracy. Apart from the leader, its only vaguely recognisable figures are Richard Tice, the former leader who is now chairman of the party; its two deputy leaders, television doctor David Bull and fleeting MEP Ben Habib; former Conservative Party deputy chairman Lee Anderson, who became Reform’s one and only MP when he defected in March; and one or two marginal figures and throwbacks like former Conservative minister Ann Widdecombe and financier and farmer Rupert Lowe. These are not stars who would shine brightly in a larger firmament.

Ideology is a different matter. There is a school of thought—though not one to which I subscribe—that the recovery of the Conservative Party lies in a harder edged, more right-wing so-called “populist” platform which emphasises strict controls on immigration, leaving the European Convention on Human Rights, stressing a patriotic British identity and opposing anything regarded as “woke”. Current data certain suggest that there is a constituency to be tapped by taking this approach, though I think it is limited and temporary, but it would be foolish to deny that, whether or not a Conservative/Reform merger comes about, the Conservative Party could come under the leadership of someone who chooses this course of action.

If I were a betting man, however, my prediction would be that this will not happen. Reform UK lacks ideological coherence, strength in depth, organisation and leadership, and the support it is currently enjoying seems to depend more than anything else on rejection of the status quo and frustrated disenchantment. As I said in City A.M. in January, I think it is a destructive force more than anything else, which does not mean I dismiss its potential electoral influence. It will do the Conservatives damage, but I suspect it will thereafter fade. There may be a protracted period of Labour government, but I am still not sure that the fundamentals of British politics are going to change dramatically. Of course, what do I know?

In 1981, when I started work in the House of Commons, I was told (though I'm not sure I believe it) that the small suite of offices off the Members Lobby which served as the Liberal Whips office (later the LibDems Whips and then the SNP) had only been wrested from the control of the Liberal Unionists, who still operated as a separate group within the Tory party (more a tribal than an ideological group it seemed) after the 1974 Liberal "revival".

Looking forward reading to this. As an American, I like a 2-party system. It's been fascinating pondering the Conservative/Reform circumstances. Reminds me in some ways of the Republican Party/Tea Party dynamic some years back. My hope is always that these dynamics serve the greater good for everybody.