The class of 2024: Labour's new (and old) blood part 1

If Labour wins a substantial majority at the forthcoming general election, here are some potential new MPs to watch

First things first: I’m taking as an assumption that Labour wins the forthcoming general election—I still expect it in October or November—with a comfortable majority. The exact size doesn’t matter, and I’m not saying I absolutely endorse this thesis. My predictions are complex and are not the point here, because I could well be wrong. So let us acknowledge that assumption and acknowledge its nature, and look at some of the potential 350-400 Labour MPs in the reconstituted House of Commons.

Douglas Alexander (East Lothian)

You remember. No, you do. Alexander was Ed Miliband’s shadow foreign secretary from 2011 to 2015 until his constituents in Paisley and Renfrewshire South chose the SNP’s 20-year-old Mhairi Black as their next representative. He was only 48 when he lost his seat, and had enjoyed a successful career in Labour politics: a fortnight after his 30th birthday, he was elected MP for his home town of Paisley in 1997 after the incumbent, Gordon McMaster, committed suicide. (McMaster left a note accusing his Labour colleague for the neighbouring seat of Renfrewshire West, Tommy Graham, of smearing him for an alleged homosexual relationship. It was a very unhappy time in West of Scotland Labour politics.)

For his first general election as an incumbent, 2001, Alexander was a campaign co-ordinator and Tony Blair rewarded him with appointment as minister of state for e-commerce and competitiveness at the Department of Trade and Industry. Eleven months later he moved across to the Cabinet Office and took charge of the Strategy Unit and the Central Office of Information as well as responsibility for the civil service. This was unglamorous and geeky but important stuff, and it suited Alexander well. As an exchange student at the University of Pennsylvania, he had worked on Michael Dukakis’s 1988 Democratic presidential campaign and worked in Congress for a Democratic senator. After graduation, he was a researcher and speechwriter for Gordon Brown as shadow trade and industry secretary. He is intelligent, sometimes a little intense, and seemed to revel in the hidden wiring of Whitehall.

In 2003 he took charge of the Cabinet Office, and was named chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster but not in the cabinet, then the following year became minister of state for trade, double-hatted at the DTI and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. After the 2005 general election, he was promoted to minister for Europe, attending cabinet but not a full member. A year later, he finally broke into Blair’s top team as transport secretary and Scotland secretary. When his old boss Gordon Brown became prime minister in June 2007, Alexander, at 40, was made international development secretary, and held the post for the rest of the Labour government.

The defeat of 2010 was badly timed for Alexander’s career. The Labour Party was suddenly out of power, with no prospect of a rapid return, and he was not quite 43. His mentor Gordon Brown resigned as leader, and he agreed to be co-chair of David Miliband’s bid to replace him, though he knew brother Ed better. Even so, when the younger Miliband formed his shadow cabinet, he gave Alexander the chunky work and pensions brief. But a reshuffle after three months saw an opening as shadow foreign secretary, and Alexander was promoted to fill it. He must have given quite a lot of thought to becoming foreign secretary during the 2015 general election, in which he was Labour’s strategy chief, but the unexpected SNP surge saw him not only not in office but out of Parliament.

After his defeat in Paisley and Renfrewshire West, Alexander threw himself into great-and-good public life, both in academia and the world of NGOs. He was a fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs from 2016 to 2022, and has been a visiting professor at the University of Chicago (2015), New York University Abu Dhabi (2020-) and the Policy Institute at King’s College London (2015-). From 2018 to 2020, he was chair of the board of trustees of Unicef UK and has been a strategic advisor for leading multinational law firm Pinsent Masons since 2016.

Alexander claims that he had not contemplated a return to political life, but in the autumn of 2022 he was approached by members of the East Lothian Constituency Labour Party, the seat currently held by Kenny MacAskill, once the SNP’s justice minister at Holyrood but now depute leader of Alex Salmond’s damp squib, the Alba Party. His majority was only 3,886 at the last election, and with Scottish Labour matching the SNP in the opinion polls, Alexander stands a good chance of an unexpected Commons return.

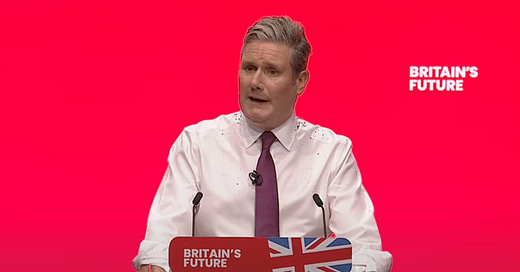

This matters. If Sir Keir Starmer forms a government this autumn, Labour will have been out of power for nearly 15 years, and the shadow cabinet is desperately short of ministerial experience. Only seven members (Lammy, Cooper, Miliband, McFadden, Healey, Benn and Smith of Basildon) have ever held government office, and only three—Cooper, Miliband and Benn—have sat in cabinet. If Alexander is returned, his nine years in ministerial positions would surely be invaluable for Starmer.

Alexander turns 57 on 26 October. He has tasted senior ministerial office as well as the palms of academia and the monetary heft of the private sector. So his future role depends partly on his and partly on Starmer. The Labour leader is likely to keep most of his current shadow cabinet in post, at least for the first year or so, but it is not impossible that, say, Hilary Benn, shadow Northern Ireland secretary and an MP since 1999, might politely decline a return to the ministerial grind; or a rearrangement of government departments might create an opportunity for an extra position. There are some who might think that Alexander would be a better, more measured and more thoughtful foreign secretary than David Lammy, who doesn’t remotely lack intelligence but can be rash and aggressive, but Starmer is reported to be happy with his international affairs team of Lammy, Healey and Nandy.

More likely is the offer of a senior minister of state post, perhaps with the right to attend cabinet and maybe with a tacit offer of promotion in the first major reshuffle. If that is Starmer’s approach, Alexander will have to think about how much work he wants to do, how strong his motivation is and what the alternatives might be: chairing a select committee, perhaps, leading one of the UK’s delegations to an international assembly or simply luxuriating in the status of “senior backbencher”. After all, he was a minister of state attending cabinet 20 years ago. If he is left out of a Labour government, it will be a waste of experience Starmer can ill afford, but, as with his departure from ministerial office in 2010, Alexander—able, earnest, articulate, erudite—finds himself at a difficult age.

Dr Miatta Fahnbulleh (Camberwell and Peckham)

Waiting to succeed Harriet Harman as Labour MP for Camberwell and Peckham is Dr Miatta Fahnbulleh, until December 2023 chief executive of the New Economics Foundation. Born in Liberia, she was brought to the United Kingdom by her parents as a young girl, and read philosophy, politics and economics at Lincoln College, Oxford, the same college as Rishi Sunak, who was the year below. She then earned an MA and a PhD in economic development at the LSE, writing her doctoral thesis on “The Elusive Quest for Industrialisation in Africa: A Comparative Study of Ghana and Kenya c. 1950-2000”.

I’ve appeared on television a couple of times with (I wouldn’t say “against”) Fahnbulleh. She’s impressive and knows Whitehall, having been head of cities in the Number 10 Policy and Implementation Unit from 2011 to 2013, but is able to translate detailed policy into language voters can understand. As someone who led a think tank making large-scale proposals for a fundamental reordering of the British economy, she is well placed (and well qualified) to talk about some of the policy areas at the heart of a Labour government’s chances of success or failure.

Will she be one of those quintessential policy wonks who more or less skips the backbenches and goes straight into government? Expect maybe a year in the parliamentary trenches but at the first reshuffle Fahnbulleh will surely be a strong candidate for a Treasury job, or a role in a super-department headed Angela Rayner looking after levelling-up, housing and local government.

Pamela Nash (Motherwell, Wishaw and Carluke)

Another victim of the SNP’s 2015 tidal wave, Pamela Nash was only 30 when she was defeated as MP for Airdrie and Shotts. She had succeeded former home secretary and general-purpose Labour hard bastard John Reid (who once, Grant Shapps avant la lettre, held four cabinet posts within a 12-month period) in 2010, having been his researcher for three years. She quickly got onto the parliamentary private secretary ladder, working for the shadow Scotland and Northern Ireland secretaries then for Jim Murphy as shadow international development secretary. (Nash had specialised in human rights and development at the University of Glasgow and spent a placement in Uganda as an undergraduate.) She also passed through my official care briefly as a member of the Scottish Affairs Committee from 2012 to 2015, of which I was clerk.

After losing her seat, Nash worked briefly for HIV Scotland then in 2017 became chief executive officer of Scotland in Union, a pro-United Kingdom campaign group founded to promote the Union on a cross-party basis. She has ploughed that furrow ever since, but last April was selected as Labour candidate for Motherwell, Wishaw and Carluke. In 2019, the SNP’s Marion Fellows had a majority of 6,268 over the Labour candidate in the broadly similar Motherwell and Wishaw seat, so a good result for Scottish Labour gives Nash a very strong chance of returning to Westminster.

Nash is sharp and poised, as anyone immersed in the gang warfare of Scottish politics has to be if they are to survive. If she comes back to the House of Commons, she knows the ropes in procedural terms, though the atmosphere has changed a great deal since 2015. But, like all Scottish Labour politicians, she has a tacit choice to make: does she stay in the cockpit of Scotland’s particular stramash, principally fighting the SNP for dominance, or does she take a broader United Kingdom view and involve herself in reserved matters like the economy, foreign affairs, defence and development? The risk of the latter course of action is feeling slightly out of the picture when returning to face the electorate in 2028 or 2029.

Hamish Falconer (Lincoln)

The Honourable Hamish Falconer had an unwitting effect on the course of New Labour at a very young age. When his father Charles applied for the candidacy in the safe seat of Dudley North, he refused when challenged to promise to withdraw his children from fee-paying schools. The selection panel instead chose barrister and law professor Ross Cranston, who served two terms in Parliament, was solicitor general for England and Wales from 1998 to 2001 and then became a judge in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice in 2007. Falconer, by contrast, was nominated to the House of Lords a fortnight after his former flatmate, Tony Blair, won a landslide majority: he was made a law officer straight away then held various ministerial posts before serving as constitutional affairs secretary and lord chancellor from 2003 to 2007.

Hamish Falconer has attracted sceptical looks for his political connections, which is at once inevitable and slightly unfair. He has a very respectable CV: after St John’s College, Cambridge, where he read social and political sciences, and Birkbeck University, he joined the civil service. He worked at the Department for International Development from 2009 to 2013 then transferred to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, serving in South Sudan, Pakistan and Afghanistan. He led the FCO’s Terrorism Response Team and was a fellow at Yale’s European Studies Council before he was selected as Labour candidate for Lincoln early last year. Conservative Karl McCartney won the seat by only 3,514 in 2019 (having previously held it 2010-17), so Falconer must be the likely victor at the general election.

Countless politicians have found a familiar name both a blessing and curse at Westminster. Falconer’s background might suggest he specialises in international affairs, but that isn’t the meat-and-potatoes of life at Westminster. Elections are won and lost, and reputations made or missed, on the economy, healthcare, education and public services. Hamish Falconer is clearly bright and accomplished, but he will have to manage somehow simultaneously to point to his substantial CV while also downplaying his accomplishments and seeming humble but eager to learn. Not an easy task.

Alan Gemmell (Central Ayrshire)

Another product of the civil service, Alan Gemmell, who recently turned 46, worked in the Home Office from 2002 to 2006, including as private secretary to the permanent under-secretary of state then spent a year as an adviser on counter-radicalisation in the Cabinet Office’s Overseas and Defence Secretariat. He then spent 11 years with the British Council, including posts in Mexico, Israel and India, before a short 16-month stint as chief executive of the Commonwealth Enterprise and Investment Council. His final role was trade commissioner for South Asia and deputy high commissioner for Western India from 2020 to 2023.

Gemmell was a young musician, playing piano and bass trombone, and toured with the National Youth Orchestra of Scotland before reading law at the University of Glasgow. In 2015, while at the British Council, he founded fiveFilms4freedom, the first global, online LGBT film programme of its kind, and in 2017 The Financial Times included him in its Top 20 Public Sector LGBT Executives. He was selected as Labour candidate for Central Ayrshire last December, but his task is more challenging than Nash’s or Alexander’s: although the constituency was represented by Labour’s Brian Donohoe from 2005 to 2015 (he held its semi-predecessor, Cunninghame South, from 1992 to 2005), at the last election Dr Philippa Whitford of the SNP had a majority of 5,304 over former Wigan Athletic and Aberdeen goalkeeper Derek Stillie of the Scottish Conservatives. The Labour candidate, Louise McPhater, trailed another 10,000 votes behind in third. Gemmell would therefore need both a strong showing by Scottish Labour and a very bad night for the Conservatives to find himself elected.

In some ways, diplomats should make excellent Members of Parliament: they are trained to be sociable and agreeable, to talk to people of all shades of opinion and backgrounds, to argue persuasively and without antagonism. They are also required to show at least superficial mastery of a wide range of subjects, and must be mentally agile and flexible. Some former diplomats have served with distinction, like Douglas Hurd, Bryan Gould and Rory Stewart; Harold Nicolson, Wendy Morton and Quentin Davies were perhaps less successful transplants. Gemmell clearly has many qualities of imagination and leadership, but putting them to use in the hardscrabble world of Westminster will be a fresh challenge, if he is given the chance.

There are some more new and returning faces whom I shall examine in another essay in the next few days. But that’s your lot for now.

Labour majority is only limited by how dreadful tories behave between now and election, and how successful lab campaign is. Unforeseen events of course may and will occur.