The church un-militant: Pope Francis waves a white flag

The head of the Catholic Church has urged Ukraine to concede to Russia's invasion simply to end the fighting, ignoring any concept of just war or self-defence: why?

I make this point every time, but, as I have written, I am not religious. I spent probably decades in comfortably evasive agnosticism but have come to the conclusion that I’m an atheist, but fear not, I don’t proselytise. However, I have some very Catholic friends, and much of my academic life has been devoted to the history of Roman Catholicism, which fascinates me. So I am, as I once unguardedly said on television, Catholic-curious. That’s the disclaimer or explanation out of the way.

It seems to me, anecdotally, that Pope Francis is the sort of pope that non-Catholics are drawn to. St John Paul II had some of that attraction, especially in his younger, more vigorous days, and his fierce battle against Soviet repression and communism was a secular cause which non-Catholics could easily endorse. It was easy to ignore his relative doctrinal conservatism, and the more fundamental fact that, as a Roman Catholic, some of his immutable beliefs were anathema to progressive opinion. Benedict XVI, of course, was more comfortably unappealing for those outside the Church, old-fashioned, intellectual, chilly, reactionary and German. But there is something about the current pontiff, the former Archbishop Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, which reaches beyond the faith.

It doesn’t matter, but I never liked him. Partly it was my instinctive if qualified suspicion of Jesuits—there is a reason the word “jesuitical” gained currency, and, I’m sorry, but St Ignatius of Loyola was a weird man—and partly it’s because, although I’m not a Catholic, I think the pope ought to be. Pope Francis, however, strikes me as someone desperate to have the approval of moderate liberal opinion, which no bishop of Rome will ever have while the Catholic Church is recognisably Catholic: unless the Church changes its stance on women priests, abortion and the sacrament of marriage, the gulf will simply be too big.

It was summed up for me by his remark in 2013 when asked about homosexuality. Now, let’s get this clear: the Church has persecuted gay people for centuries while also thriving on their contribution, which is a deeply unpleasant way to treat people, I don’t care what consenting adults do with their genitals and if Catholicism is losing some of its hypocrisy on the issue that I’m as happy as the next man. But the pope was asked specifically about gay clergy, and his response was “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” Well, you’re the pope, and there is an argument that a bit of judging goes with the territory, especially as the question touched not only on sexuality but on clerical discipline, which is definitely in Francis’s wheelhouse. (One should also note that it was not the liberal “Eureka!” moment some people might like to imagine. The pope reiterated that homosexual acts were sinful, but that being gay in itself was not. So, the Church doesn’t mind your “nature”, just please don’t follow it.)

The “Who am I to judge?” summed up his chummy, all-things-to-all-men, split-the-difference approach to really difficult moral, ethical, personal and sexual issues. It is probably an admirable trait in many or most people, but for the head of a church, it makes me wonder why you turned up at all if you don’t like the rules. Of course the Holy Father did not seek his office: God’s favour was indicated by two signs. One took place in the conclave following Benedict XVI’s abdication, so we will never know what it was, but the other was revealed by Christoph Cardinal Schönborn, the aristocratic archbishop of Vienna and a Dominican friar: just before the conclave began, the cardinal encountered a Latin American couple he knew, and asked for their advice in the forthcoming deliberations. The woman whispered in his ear the name “Bergoglio”, which—understandably enough, as it was the name of a cardinal present in Rome—he took to be significant, saying “it hit me really: if these people say Bergoglio, that’s an indication of the Holy Spirit.” The Argentinian cardinal was elected on 13 March 2013, the second day of the conclave, at the fifth ballot.

(Two days is child’s play: the longest papal election, after the death of Clement IV in 1268, lasted just under three years, Gregory X emerging as the agreed candidate on 1 September 1271. He issued the papal bull Ubi periculum in 1274, translated as Canon 2 here, which set out the rules for conclaves that still apply now and were designed to avoid the protracted struggle which had seen him become pontiff.)

All of this is scene-setting for Pope Francis’s taste for geopolitics. The Church of course has a temporal role, and one interpretation of the papal tiara, which has not been used since 1963, is that the three crowns symbolised the pope’s authority as universal pastor, his universal ecclesiastical jurisdiction and his temporal power. Or it may represent the threefold nature of Christ, as priest, prophet and king. In any event, the pope has always had one foot in the worldly and political camp, and was temporal sovereign ruler of the Papal States, in central Italy, until 20 September 1870, which is not so very long ago. Indeed he is still: the Lateran Treaty of 11 February 1929, signed with the fascist leader Benito Mussolini, then prime minister of the Kingdom of Italy, recognised the Vatican City as an independent state.

As I mentioned above, St John Paul II was an active international diplomat. As a Pole, Karol Wojtyła was not only from behind the Iron Curtain—he had been archbishop of Kraków before his election—but he was the first non-Italian pope since 1523, and went on to be the third-longest reigning pontiff in history. He travelled more than any other pope had ever done, and visited 129 countries, making him one of the most widely travelled leaders ever. His part in the collapse of communism was considerable: the historian Timothy Garton-Ash expressed it succinctly when he said:

Without the pope, there would have been no Solidarity movement; without Solidarity, there would have been no Gorbachev; without Gorbachev, there would have been no 1989. The pope was crucial at every stage.

If we doubt a Western source, Mikhail Gorbachev himself said after John Paul’s death of the fall of communism, “It would have been impossible without the pope”.

Pope Francis has maintained this tradition of papal diplomacy, even if he is not quite cut from the outsized, heroic cloth of his Polish predecessor. In 2014, he hosted talks between President Barack Obama and the Cuban leader Raúl Castro, first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, which led to the relative normalisation of relations between the United States and Cuba, though President Donald Trump reimposed some restrictions in 2017. These were in turn partially reversed in 2022.

His interventions in the Middle East have been less successful. He visited Israel in 2014 but there were protests, and he courted controversy in 2015 when he invited Mahmoud Abbas, president of the Palestinian National Authority, to the Vatican and signed a treaty recognising the State of Palestine; the jurisdiction is still only recognised by 139 of the 193 members of the United Nations, where it is according to UN General Assembly Resolution 67/19 a “non-member observer state”. There was more furore when it was initially reported by the media that Pope Francis had called Abbas an “angel of peace”. In fact he told the Palestinian leader, “The angel of peace destroys the evil spirit of war. I thought about you: may you be an angel of peace.”

His attitude to the war in Ukraine has been odd. One naturally expects the Holy Father to be generally in favour of peace, the Crusades and other religious wars notwithstanding, and shortly after the Russian invasion in February 2022, he visited Russia’s embassy in Rome. He then spoke to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine by telephone, and assured him of the Vatican’s attempts to find “room for negotiation”. In May, speaking to the Jesuit magazine La Civiltà Cattolica, he said the Russian invasion had been “perhaps somehow either provoked or not prevented”. He added:

Someone may say to me at this point: but you are pro-Putin! No, I am not. It would be simplistic and wrong to say such a thing. I am simply against reducing complexity to the distinction between good guys and bad guys, without reasoning about roots and interests, which are very complex.

Setting aside the peculiarly self-denying ordinance of the pope refusing to distinguish between “good” and “bad”, Francis is not a fool, and must have been aware that this hesitation and prevarication played directly into the false Russian narrative of NATO having provoked the conflict. In August he peddled another Kremlin talking point when he described the death in a car bombing of the hardline Russian nationalist Darya Dugina, a prominent supporter of the invasion, as an example of “the madness of war”, calling her an “innocent victim”. The pontiff need not have wanted her dead to stop short of singling out a strong partisan of the conflict, who had dismissed reports of Russian war crimes as staged, for special sympathy.

In October 2022, after President Putin had raised the spectre of using nuclear weapons, Francis asked Zelenskyy to be receptive to “serious peace proposals”. He conceded a month later that “Certainly, the one who invades is the Russian state. This is very clear.” At the same time, when asked about the atrocities committed by Russian forces, he seemed keen to exonerate the Russians themselves.

When I speak about Ukraine, I speak about the cruelty because I have much information about the cruelty of the troops that come in. Generally, the cruellest are perhaps those who are of Russia but are not of the Russian tradition, such as the Chechens and Buryats and so on.

This was regarded is some circles as a blatantly racist as well as baseless accusation.

This weekend Pope Francis has returned to the subject. An interview recorded last month with Swiss broadcaster RSI revealed that he urged Ukraine, again, to reach a settlement.

I think that the strongest one is the one who looks at the situation, thinks about the people and has the courage of the white flag, and negotiates. The word negotiate is a courageous word. When you see that you are defeated, that things are not going well, you have to have the courage to negotiate.

Vatican spokesman Matteo Bruni insisted that Francis had used the phrase “white flag” only after the interviewer had introduced it, meaning it to signify something “to indicate a stop to hostilities (and) a truce achieved with the courage of negotiations”.

As an isolated incident, this would be a clumsy, tactless and mendacious formulation, one which placed the onus on Ukraine, rather than the aggressor, Russia, to initiate an end to the conflict in the context of surrender. Taken as part of a pattern of behaviour stretching back to the very beginning of this phase of the conflict in February 2022, it is little short of disgraceful. The pope has again and again pandered implicitly or explicitly to a false Russian narrative of provocation and self-defence, and consistently played down the right of Ukraine to resist and to seek to recover territory annexed illegally from it. He has granted Vladimir Putin every benefit of the doubt and sought to temporise, projecting the misleading impression that the war in Ukraine is a vastly knotty problem with faults on both sides and no discernible moral dimension.

What is Pope Francis up to? The most innocent explanation is that, as a religious man, he is so overwhelmingly focused on bringing the fighting and the death to an end that he will accept, and indeed advocate, any measures which achieve that. But the Church’s position is not a simple pacifist one. It has a long tradition of carefully calibrated thinking on conflict, founded in part on Romans 13:4.

But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain: for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil.

In the 5th century AD, St Augustine of Hippo constructed the theory of “just war”. In The City of God, he argued:

They who have waged war in obedience to the divine command, or in conformity with His laws, have represented in their persons the public justice or the wisdom of government, and in this capacity have put to death wicked men; such persons have by no means violated the commandment, ‘Thou shalt not kill’.

The conditions for a just war were heavily circumscribed. “No war is undertaken by a good state except on behalf of good faith or for safety,” Augustine wrote.

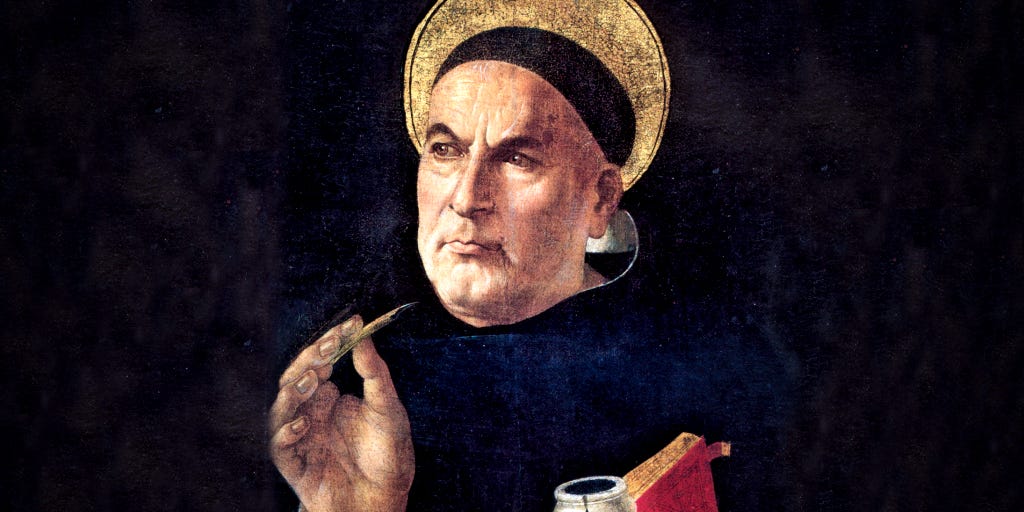

In the 13th century, the idea was refined by the Dominican friar St Thomas Aquinas. There were, he stipulated, three conditions which had to be met for a war to be just: it had to be at the command of a lawful sovereign; it had to have a just cause; and the belligerents had to be possessed of rightful intentions, “so that they intend the advancement of good, or the avoidance of evil”. Essentially, Aquinas found, “Those who wage war justly aim at peace, and so they are not opposed to peace”.

If we reject—and we should—the argument that Russia invaded Ukraine to protect its legitimate interests, rather than to influence the foreign policy and international alliances of neighbouring countries, then there is at least a prima facie case for saying that Ukraine’s pursuit of military action against Russia falls within the scope of just war as developed by Augustine and Aquinas. In other words, it would not work to plead that the pope wanted the conflict to end simply because war is bad.

It is certainly true that the number of deaths caused by the conflict since February 2022 has been monstrously high. There are no generally agreed figures, but British and American intelligence suggests that around 350,000 Russian soldiers have been killed or wounded, of whom between 45,000 and 120,000 are fatalities. US estimates put the number of Ukrainian military dead at 70,000, while President Zelenskyy recently admitted to a lower figure of 31,000. In addition, the United Nations claims that at least 10,000 civilians have died, although “the actual numbers are likely significantly higher”. It is, by any estimate, a terrible butcher’s bill, and anyone, whether it is Pope Francis or a parish priest, can be forgiven for wishing fervently that the killing would stop.

We must take into account, however, an improbable combination of Catholic teaching on just war—that a conflict can be justified on the grounds of safety and protection, as the defence of Ukraine certainly is—and likely geopolitical consequences. If Ukraine were to sue for peace with a fifth of its territory under Russian control, even a settlement which froze the status quo would amount to a qualified success for Putin. He would be left in possession of Crimea, and its all-important naval base at Sevastopol, the headquarters of the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet. This represents Russia’s only true warm-water port: the Pacific Fleet is based at Fokino, close to Vladivostok, which freezes in winter although it can be kept open by ice-breakers; Baltiysk, the main base of the Baltic Fleet, is in the Kaliningrad Oblast and therefore not contiguous with Russia proper, while its second base at Kronstadt freezes in winter; and the Northern Fleet is based at Severomorsk on the Kola Peninsula, in the far north.

In addition to rewarding Putin with a naval base from which he could project power through the Black Sea into the Mediterranean, ending the conflict with the status quo would send a dangerous signal about the West’s lack of resolution. It would suggest to Putin that our willingness to support an ally which was attacked had strict limits in men and materiel, and likely encourage him to look at his next expansion. It is hard to think he would not be emboldened when looking at the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, all of which have been under Russian (Soviet) occupation within living memory.

A sudden papal peace, therefore, would be significantly to Russia’s advantage, and to the severe detriment not only of Ukraine but of any of Russia’s neighbours, effectively marking them as fair game if Putin was willing to pay a high enough price in blood (or have others pay it for him). The primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Sviatoslav Shevchuk, major archbishop of Kyiv-Galicia, has disagreed with his religious superior’s latest sentiment.

We fear that these words will be understood by some as an encouragement of this nationalism and imperialism which is the real cause of the war in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, to eradicate any doubt as to who would benefit from a Ukrainian surrender, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said:

The pontiff knows Russian history and this is very good. It has deep roots, and our heritage is not limited to Peter [the Great] or Catherine, it is much more ancient.

This reiterates the pseudo-historical justification for the invasion which President Putin has consistently promoted, most recently in his long interview with American commentator Tucker Carlson (about which I have expressed my thoughts). If the Russian government is endorsing your approach to Ukraine, your approach is probably wrong.

Is there more than poor judgement behind the pope’s stance? As I said, this is not an isolated incident. It is telling that he chose to advise Ukraine to have the “courage of the white flag”, rather than call for a Russian withdrawal of any kind. John Allen, editor of Catholic journal Crux, has suggested that Francis’s origins in Peronist Argentina give him an instinctive antipathy towards the West. He has written:

Francis is, of course, history’s first pontiff from the developing world, and he reigns at a time when the demographic center of gravity in Catholicism clearly has shifted. Today, more than two-thirds of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics live outside the West, a share that will be three-quarters by mid-century. In such a world, it’s only logical that the Vatican’s geopolitical homing instincts increasingly will more closely resemble those of, say, the African Union, or India, or even the OPEC states, than those of Washington and Brussels.

The pope has also shown enthusiasm for an ecumenical outreach to the Russian Orthodox Church; but Kyrill, patriarch of Moscow and All Rus’, the head of the Russian church, has endorsed the invasion of Ukraine, which is regarded as part of Orthodoxy’s “canonical territory”, and blessed Russian soldiers fighting there.

Pope Francis has got this badly wrong, and has been exposed as a fool or a knave. If he is simply overwhelmed by the scale of the death, then he has no business in the arena of international diplomacy, where hard choices need to be faced and actions have consequences. A well-meaning surrender by Ukraine now would represent a defeat for the Ukrainian people and expose them to further danger, as well as rewarding Russian aggression. If the pope cannot see that, he should confine himself to matters of religion.

If, on the other hand, he knows what he is doing, and is pursuing a strategic agenda which favours Russia’s interests because Vladimir Putin is somehow a champion against Western imperialism, he has shown himself morally void. Not only is Putin an autocrat and a kleptocrat who has extinguished for the time being any embers of democracy in Russia, he regularly has political opponents murdered, oversaw a brutal war of repression in Chechnya which killed tens of thousands of civilians as well as military personnel and has systematically curtailed and abused human rights in Russia. If, as the pope presumably believes, there is a reckoning after this life, a decision to stand beside Vladimir Putin will require a great deal of explanation.

It may be that Pope Francis has little sway in the current circumstances. Neither Russia nor Ukraine is predominantly a Catholic country, and, for all that President Biden burnishes his Roman credentials (while supporting equal marriage and access to abortion), there is little indication that the US administration is in thrall to the Vatican. We may, for the moment, ascribe the pope’s call for the “courage of the white flag” to stupidity; but we should regard it as another piece in a growing mosaic of accommodating Russia, diminishing the rights of Ukraine and attempting to muddy the waters of the ongoing aggression.

As a practicing Catholic, I fully support the direction in which Pope Francis is leading the Catholic Church. Its not about impressing liberal opinion (that will never happen). Its about giving new hope and energy to the existing faithful. I find the thought of an atheist with an ancestral suspicion of Jesuits telling the Pope he should be more Catholic amusing! However, I agree he has got things badly wrong on Ukraine. (I note the Secretary of State, Cardinal Parolin, has done his best to walk back the Pope's remarks.) I have no doubt that Francis is primarily moved by horror at the 30K+ Ukrainians who have been killed and the probably greater number of Russians who have died. If the Ukrainians listened to his advice, they would probably end up up with a "peace treaty" in which Russia would gain Eastern Ukraine and Crimea, leaving Putin free to rearm and come back for more when he felt ready, leading to yet more deaths. But if the West is not prepared to give the Ukrainians the weapons they need for an outright victory, would it not better to tell them that so they can make their own decision as to how best their nation can be preserved in these horrific circumstances? The Catholic Church in Ireland had a long history of advising their congregation not to rebel against what most of them regarded as an unjust foreign occupier, but to pursue their objectives through peaceful means. I believe one of the conditions St. Thomas Aquinas set down for a "just war" was that there should be a realistic prospect of success?