Sunday round-up 9 March 2025

Cake'n'candles for Brian Redman, John Cale, Linda Fiorentino and Juliette Binoche, David Rizzio met a messy end and you're praying to the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste

Who is glad today is not the working week so they can enjoy their birthday at leisure? The lucky boys and girls include screen veteran and Danny Kaye Show regular Joyce Van Patten (91), Burnley-born endurance racing maestro Brian Redman (88), Velvet Underground star, composer and producer John Cale (83), soi-disant “BTK” serial killer Dennis Rader (80), Procol Harum guitarist Robin Trower (80), former European Commissioner and Italian foreign minister Emma Bonino (77), disgraced former Conservative MP and inexplicable one-time leader of the UK Independence Party Neil Hamilton (76), former England rugby captain and Question of Sport habitué Sir Bill Beaumont (73), currently-on-the-lam Lebanese-French-Brazilian former CEO of Renault and Nissan Carlos Ghosn (71), double World Sportscar Champion Teo Fabi (70), famously intelligent former Conservative minister Lord Willetts (69), actress, photographer and possessor of “raven hair, intense gaze and low voice” Linda Fiorentino (67), Academy Award- and César-winning actress Juliette Binoche (61), nominated US Ambassador to Greece, former fiancée of Donald Trump Jr and ex-Fox News presenter Kimberly Guilfoyle (56), former England rugby captain Martin Johnson (55), New York Yankees (Evil Empire booo) manager Aaron Boone (52), rapper and actor Bow Wow (37) and YouTube mocker of “life hacks” Khaby Lame (25).

Missing out on the celebrations for the valid reason of being dead are luminaries-without-the-lumen including Florentine explorer and supposed inspiration for a continent’s name Amerigo Vespucci (1451), journalist, agrarian and parliamentary reformer William Cobbett (1763), industrialist, former Governor and United States Senator of California and founder of the eponymous university Leland Stanford (1824), long-serving Soviet foreign minister and cocktail enthusiast Vyacheslav Molotov (1890), novelist, poet, garden designer and prominent lesbian Vita Sackville-West (1892), composer and pianist Samuel Barber (1910), sailor, advertising executive, racist and founder of the American Nazi Party George Lincoln Rockwell (1918), crime novelist Mickey Spillane (1918), Senator for New York, State Department official and US Court of Appeals judge James Buckley (1923), first human in space and reliably vodka-adjacent Yuri Gagarin (1934), actor Raúl Juliá (1940), chess grandmaster and hobbyist antisemite Bobby Fischer (1943), Hawkwind lead singer Robert Calvert (1945), actress and animal welfare activist Alexandra Bastedo (1946) and convicted terrorist and fleeting Member of Parliament Bobby Sands (1954).

Stabbing pains

Today in 1566, at around 8.00 pm, Mary Queen of Scots was taking supper in a small room off her bedchamber in the Palace of Holyroodhouse. Eating with her were her illegitimate half-sister Jean, Countess of Argyll, Master of the Household Robert Beaton of Creich, Arthur Erskine of Blackgrange, the Master of Horse, and the Queen’s Italian private secretary, David Rizzio.

Mary was 23 years old and six months pregnant by her new husband (and first cousin) Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, whom she had married the previous July. In superficial dynastic terms, Darnley was a good choice of mate: like Mary, he was a grandchild of Henry VIII’s sister Margaret Tudor, who had married King James IV of Scotland, so any offspring they might produce would have a powerful claim on the English throne, and he was also descended from Mary Stewart, Countess of Arran, daughter of James II. But in truth she had married for love, or perhaps lust: Darnley was nearly four years younger than Mary, good-looking and over six feet tall, no minor consideration as the Queen herself stood at six feet.

It was the young man’s character which made the marriage a disaster waiting to happen. Darnley was proud, vain, arrogant and ambitious, as well as sexually incontinent, probably not just with women. He drank too much and had a streak of petulant violence in him. As Mary’s husband, he was King Consort, but he wanted more, demanding what Scots law called the Crown Matrimonial, the right to be a full co-ruler with his wife. It would also allow him to remain King if she predeceased him. Mary, clever and charismatic, was possessed of quite spectacularly poor judgement and had no wisdom at all—what 23-year-old does?—but even she would not countenance Darnley fully as King. By the autumn of 1565, barely six months after their wedding, the marriage was souring, and Darnley was growing jealous of Mary’s close relationship with her secretary Rizzio. When it became clear the Queen was pregnant, there were inevitable rumours that Rizzio rather than Darnley was the father. A French diplomat reported a story that Darnley had found Rizzio in the Queen’s bedchamber in the middle of the night with only a fur gown over his shirt.

Davide Rizzio was in his early 30s, scion of an aristocratic Piedmontese family and born in Pancalieri near Turin. He had searched for advancement in a succession of noble households, each time in vain, until in 1561 he became attached to the Count of Moretta, an ambassador of the Duke of Savoy. Rizzio accompanied Moretta on an embassy to Scotland, but the Count found he had no use for him and he was released. However, a good musician and an excellent singer, Rizzio had befriended three of the musicians who had accompanied Mary from France and soon his talent and foreign exoticism drew the Queen’s attention too. Towards the end of 1564, she appointed him her secretary for relations with France; the presence of a foreigner so close to the Queen was unpopular with many Scottish courtiers, but Rizzio was ambitious too, tightly controlling access to Mary and seeing himself more as a powerful officer of state than a functionary.

It is easy to see how Rizzio alienated others. He was acquisitive and reasonably corrupt, open to bribes and gifts and probably living beyond his means. He dressed flamboyantly, favouring velvet hose, satin doublets, furs and jewels. He could be charming and witty, though several of his enemies recorded that he was short, hideously ugly and deformed, possibly afflicted by a curvature of the spine. Were he and the Queen lovers? It is impossible to say, though it is ironic that an historian 80 years later, David Calderwood, would record that Rizzio had been in a sexual relationship with Darnley: he had “insinuated himself in the favours of Lord Darnley so far, that they would lie some times in one bed together”.

It seems harsh to say, given he was only 19, but Darnley seems to have had very few redeeming features. My old tutor Professor John Guy described him as “a narcissist and a natural conspirator”. By the first months of 1566, jealous, frustrated and feeling both betrayed and belittled, he wanted harm to come to Rizzio and found no shortage of sympathisers. He entered into a conspiracy with a group of Protestant lords including his father, the Earl of Lennox, the Secretary of State, William Maitland of Lethington, and the Queen’s half-brother, James, Earl of Moray, which was hopelessly elaborate and involved Darnley being declared King by the Protestant lords in a parliament, in exchange for which he would effectively restore the Presbyterian Reformation settlement. This would be a substantial change of tack for Darnley, politically and religiously, but the masterstroke was to be accusing Rizzio of having misled him and poisoned his mind. That made it inevitable that Rizzio would have to be eliminated.

We return to the Queen and Rizzio at supper that 9 March 1566. Darnley arrived at the Palace of Holyroodhouse with around 80 armed men and overpowered the royal guards. He burst into the tiny room where his wife was eating, but before he could say more than a few words, another conspirator, Lord Ruthven entered wearing full armour and announced that Rizzio had offended the Queen’s honour. Mary, reckless but quick-witted, saw violence impending but was angry: “Leave our presence under pain of treason!” she told Ruthven, who then instructed Darnley to seize hold of his wife. It was now chaos: Rizzio hid fearfully behind the Queen, who rose in fury to resist Darnley, while the other diners attempted to ward off Ruthven until he drew his dagger. Mary would say later that Patrick Bellenden, another plotter, pointed a gun at her pregnant stomach, while Andrew Kerr of Faldonsyde threatened to stab her.

Ruthven and another man stabbed Rizzio and dragged him, screaming, from the room into the adjacent Audience Chamber, where he was stabbed 57 times and his body was thrown down the stairs. It is said his bloodstains are still visible on the floorboards of the chamber. The final blow was struck, symbolically, with Darnley’s own dagger, though he was not the one to wield it. Of course he wasn’t. The conspirators left the Queen under armed guard, but she seems to have found a few moments to speak to Darnley, “beguiled him with soft words” and persuaded him that they were both in danger. Two nights later, they escaped Holyroodhouse together, first to Seton Palace and then Dunbar Castle, and Mary returned to the capital on 18 March with 5,000 soldiers and resumed control.

Full disclosure: for all her faults, I am an enormous fan of Mary Queen of Scots, because she was clever, brave and genuinely well-intentioned (mostly). Consider this: she saw armed men led by her increasingly estranged husband butcher one of her closest courtiers in front of her and threaten her with violence. She was six months pregnant and a man aimed a pistol at her unborn child. And she was 23 years old. How did she react? She shouted at them and tried to remind them of their station until she was manhandled away while Rizzio shrieked and bled. Already she was able to focus enough to assess the situation and decide she had to co-opt her husband if she was going to escape. That took courage and character.

Darnley? Eleven months later, at around 2.00 am on the night of 9/10 February 1567, the provost’s house at Kirk o’Field in Edinburgh, where he was staying, was destroyed by two huge explosions. Darnley’s body, dressed only in a nightshirt, was found with that of his valet, William Taylor, along with a cloak, a dagger, a chair and a coat. His body showed no marks of strangulation or any other violence, and a post-mortem examination concluded he had been killed by internal injuries from the explosion. He was 20 years old. Mary had been considering ways of freeing herself of Darnley the previous autumn. Was she involved in his death? You tell me.

I think I’ve got an idea…

Staying north of the border, on this day in 1776, W. Strahan and T. Cadell published the first edition of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith. Known as The Wealth of Nations, it was produced in two volumes, the first comprising Books I, II and III, the second Books IV and V, and the initial print run of 500 or 750 sold out within six months. Four more editions were produced within 13 years. Smith, a native of Kirkcaldy on the Fife coast, studied moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow then won the Snell Exhibition to undertake postgraduate studies at Balliol College, Oxford (which, compared to Glasgow, he found hidebound and stifling). Under the terms of Sir John Snell’s bequest, he was supposed to take holy orders in the Anglican church and return to Scotland; certainly he fulfilled the latter. From 1748 he lectured at the University of Edinburgh under the patronage of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, and in 1751 was appointed a professor at the University of Glasgow teaching courses in logic. The following year he became Professor of Moral Philosophy, holding the position for 12 years.

In 1759, Smith published his first work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, in which he proposed that the search for “mutual sympathy of sentiments” through social interaction led to the development of conscience. This, he proposed, was how people developed a sense of morality. In 1764, he resigned his chair in Glasgow to become tutor to the 17-year-old Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, his appointment arranged by the Duke’s stepfather Charles Townshend, Member of Parliament for Harwich and shortly after to become Chancellor of the Exchequer. Educating the young Duke was twice as well paid as his academic position, and he toured Europe with his pupil, meeting Voltaire in Geneva and Benjamin Franklin in Paris. Smith was also exposed to François Quesnay’s idea of physiocracy, which in opposition to the prevailing mercantilist view of the world preached a non-interventionist gospel summed up as Laissez faire et laissez passer, le monde va de lui même! (“Let do and let pass, the world goes on by itself!”).

In 1766 Smith gave up his tutorial duties and returned to Kirkcaldy, where he would spend most of the next decade refining the ideas and theories for his next book. The Wealth of Nations was one of the first attempts to do something seemingly straightforward, and describe what made a country’s economy successful and prosperous. He argued that division of labour increased production more than any other single factor. It drove efficiency, and its effect was more marked in manufacturing than in agriculture. He was opposed to measures which distorted the operation of markets such as subsidies and tariffs, and struck at two of the foundations of mercantilism, protectionism and the belief that large bullion reserves were a prerequisite of economic success.

The Wealth of Nations really was a book which changed the world. It didn’t just challenge one prevailing ideology, but meticulously and rigorously showed why that ideology was built on insufficient understanding of how the world worked. Its influence was immediate: in the first budget after its publication, the Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord North, drew from it two new taxes, on manservants and property sold at auction, while the following year saw the introduction of inhabited house duty and malt tax. In 1779, Smith was consulted by Henry Dundas, the Lord Advocate, and the Earl of Carlisle, First Lord of Trade, about introducing free trade in Ireland. By the end of the 18th century, The Wealth of Nations had been translated into French, German and Spanish, and for centuries was more cited than any other economic work apart from Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

Adam Smith essentially invented classical economics with The Wealth of Nations. It was one of the first major attempts to understand economies as the personal rule of autocratic monarchs began to cede its place to broader based national and at least semi-representative governments. It was, for many, the day the world changed.

Ora pro nobis, but only if it’s no trouble

If it’s red-letter days you’re looking for, today we are remembering the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste (d AD 320), Roman soldiers of the XII Legion who were condemned to stand naked on a frozen pond overnight then (ironically) burned at Sebaste (modern-day Sivas in central Turkey), their ashes cast into the river; St Pacian (AD 310-AD 391), a Father of the Church who was Bishop of Barcelona and argued against Novatianism; St Frances of Rome (1384-1440), a high-born Roman who enjoyed a 40-year arranged marriage to the commander of papal forces in Rome, founded a lay consorority under the supervision of the Order of Our Lady of Mount Olivet and as a widow for the last four years of her life lived in its only house, the Monastery of Tor de’ Specchi near the Campidoglio, and is invoked by widows and car drivers; and St Catherine of Bologna (1413-63), an aristocrat who became a Poor Clare at the convent of Corpus Domini in Ferrara, latterly as Mistress of Novices, became abbess of a new convent in her home city, experienced visions and premonitions and is patroness of artists and against temptations (connected?).

In Lebanon, it is Teachers’ Day or Eid al Moalim, when pupils present their teachers with gifts.

Factoids

For those who have heard of William Bligh, he is “Captain Bligh”, who inspired perhaps the famous naval mutiny in history on board HMS Bounty. In fact, when the mutiny took place in 1789, he was only a lieutenant, and he ended his career as a vice-admiral, so the “captain” is something of a misnomer except insofar as he was captain of HMS Bounty and, indeed, the only commissioned officer on the ship (she was a small cutter with a crew of only 44), though Fletcher Christian, the master’s mate who led the mutiny, was an acting lieutenant. Only 34 at the time of the mutiny, Bligh lived to the age of 63, commanded HMS Director at the Battle of Camperdown in 1797, for which he was awarded the Naval Gold Medal, and HMS Glatton at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. From 1806 to 1808 he was Governor of New South Wales; awkwardly he was faced with another mutiny, the so-called Rum Rebellion, during which he was deposed as Governor and had to flee.

Whatever his faults as an excessively strict disciplinarian, in the aftermath of the mutiny on board HMS Bounty, Bligh conducted an act of extraordinary seamanship. With 18 members of the crew who had remained loyal, he was cast adrift in a 23-foot launch with food and water for around a week, a quadrant and a compass, but neither charts not a marine chronometer. The nearest European settlement was at Timor in the Dutch East Indies, more than 4,000 miles away. An attempt to find supplies on the nearby island of Tofua was abandoned when they were attacked by the local population and the quartermaster, John Norton, was killed. Using a pocket watch owned by the gunner, William Peckover, Bligh navigated the launch safely to Timor via a series of islands in 47 days, the crew reduced to 40 grams of bread a day. When they reached Coupang in Timor on 14 June 1789, he insisted that a makeshift Union Jack be flown as they arrived, according to naval protocol. Three of his crew died shortly after arriving, possibly from malaria, while two more died on the journey back to England.

Christian’s elder brother Edward attended the oldest college at the University of Cambridge, Peterhouse, but transferred to St John’s College, the second wealthiest behind Trinity, after two years, where he befriended future slave trade abolitionist William Wilberforce. In 1779, he graduated as Third Wrangler, the student with the third-highest examination marks of those who gain a first-class degree in the Mathematical Tripos (then formally known as the Senate House Examination). Christian was briefly headmaster of Hawkshead Grammar School in Cumbria, then was admitted to Gray’s Inn in 1782, returning to St John’s as a fellow; he was called to the Bar in 1786. In 1788, he became the first Downing Professor of the Laws of England at Cambridge and the university’s first Professor of Common Law, becoming a fellow of Downing College when it was established in 1800. That same year he became Chief Justice of the Isle of Ely, exercising jurisdiction in all matters of civil and criminal law on behalf of the Bishop of Ely (this jurisdiction was abolished by the Liberty of Ely Act 1837). He also edited the 12th edition of Sir William Blackstone’s The Commentaries on the Laws of England, published between 1793 and 1795. It seems unfair he is remembered, if at all, as the brother of a mutineer.

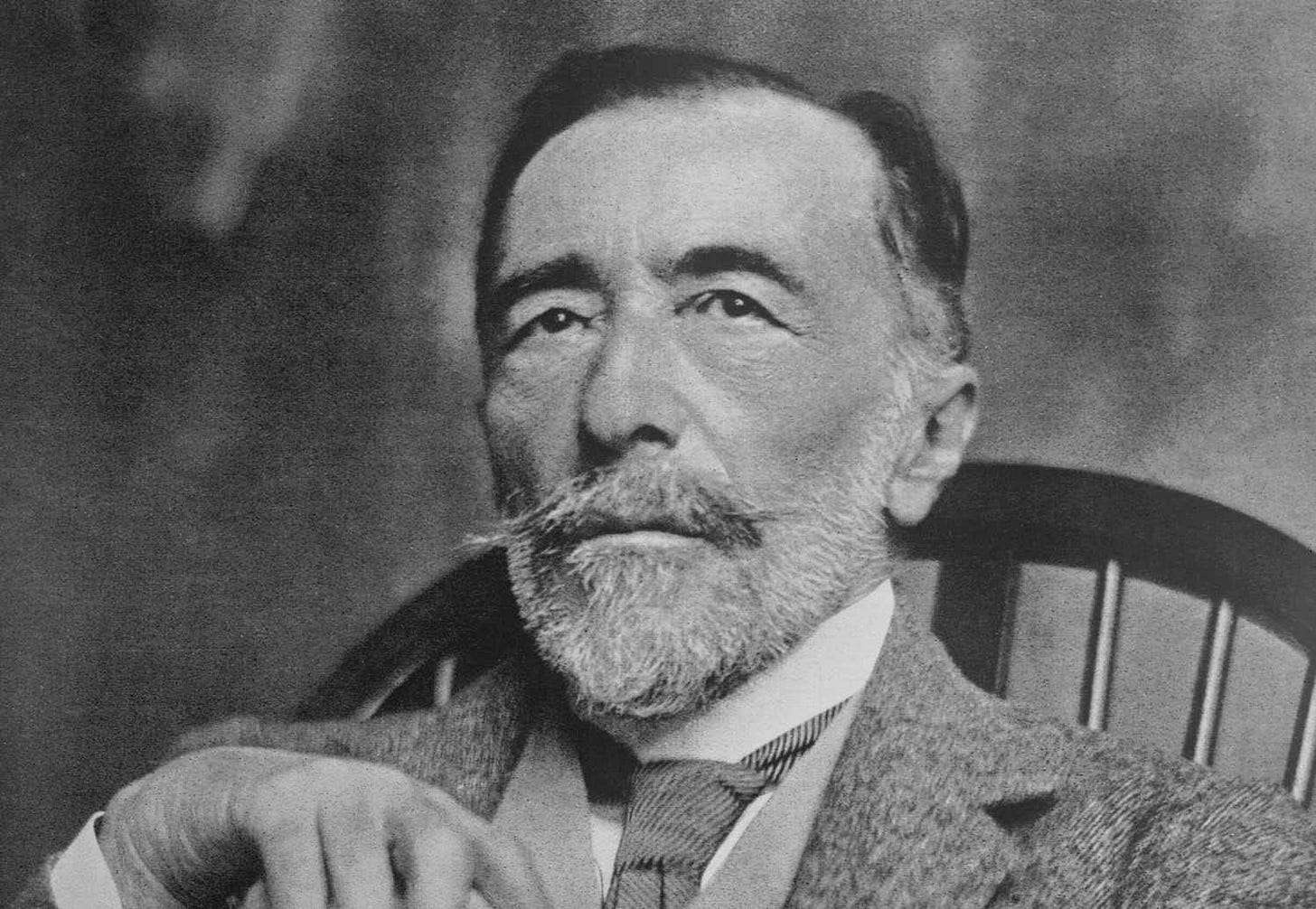

I’ve been thinking about Heart of Darkness this week (see below). Its author Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski) was writing in his third language, having only mastered English fully in his 20s after growing up speaking Polish and correctly accented French. A surprising number of successful and famous authors wrote in English despite it not being their native tongue, a feat to me of incomprehensible brilliance: Arthur Koestler (Hungarian), Ayn Rand (Russian), Karen Blixen (Danish), Roald Dahl (Norwegian), Alistair MacLean (Gaelic), Vladimir Nabokov (Russian), Chinua Achebe (Igbo), Jack Kerouac (French), Sir Tom Stoppard (Czech), Sir Kazuo Ishiguro (Japanese), Elif Shafak (Turkish), Yann Martel (French) and Gary Shteyngart (Russian).

Since 1958, the United States and the United Kingdom have had a Mutual Defence Agreement which governs cooperation on nuclear weapons. It has been amended and extended 10 times, and on 14 November 2024 was extended indefinitely. The agreement has its roots in the Quebec Agreement concluded by Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt at the Quebec Conference on 19 August 1943, after which there was a second conference in the city in September 1944. Just after the conference, Churchill and Roosevelt travelled to the latter’s Springwood estate at Hyde Park in southern New York State and drafted a memorandum on post-war cooperation which is recorded as the Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire. Its main element was that the two countries should continue to work closely together once the Second World War had ended. By June the following year, after Roosevelt’s death and shortly before Churchill’s election defeat, Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson was Chief of the British Joint Staff Mission to Washington DC and British representative on the Combined Policy Committee which oversaw US/UK relations on nuclear weapons. He made a not-unreasonable request to see the original text of the aide-mémoire, but there was some prblems. The Americans couldn’t find the hard copy of the document, and it had been negotiated by Roosevelt with only two advisers, Harry Hopkins and Admiral William Leahy, Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief; however, by June 1945 Hopkins was dying of advanced stomach cancer, while Leahy, who was sceptical about nuclear weapons in any case, hadn’t really paid attention and had a very muddled recollection of what had been agreed. In July, disaster was averted when the British found a photocopy of the aide-mémoire, although for a while Major-General Leslie Groves, who was in charge of the military aspects of the Manhattan Project, questioned its authenticity. The original was eventually found in the papers of Roosevelt’s naval aide, Vice-Admiral Wilson Brown Jr, misfiled: it was headed “Tube Alloys”, the codename of the original Anglo-Canadian nuclear weapons project, and someone who knew nothing about Tube Alloys assumed it to be connected with guns or pipes and put it in the wrong file. Still, all was well in the end, eh?

If you are a regular reader you may well have been reminded at some point that the title of “Prime Minister” began in Britain as an insult to Sir Robert Walpole who, as the chief minister of George I and George II and now marked as “the first prime minister”, accusing him of gathering too much power in his own hands and becoming an overmighty subject. You may further recall that (with two exceptions) the Prime Minister’s formal title was, and is, First Lord of the Treasury, and that the style of “Prime Minister” does not appear in statute until the Chequers Estate Act 1917. Yet we all know that the Chancellor of the Exchequer is the ministerial head of HM Treasury. So what is going on? In fact the Chancellor carries an additional title of Second Lord of the Treasury, which begins to untangle things. British constitutional practice allows for offices of state, rather than being occupied by a single person, to be carried out by a group of people, a practice known as putting into commission. In 1612, for the first time the office of Treasurer of the Exchequer, held alongside that of Lord High Treasurer, was put into commission, the Earl of Northampton becoming First Lord of the Treasury with five other Lords Commissioners. Throughout the rest of the 17th century and into the 18th century, it became increasingly common to put the office into commission: it was held in that way 1612-14, 1618-24, 1624-36, 1641-43, 1660, 1667-72, 1679-85, 1687-1702 and 1710-11. The last Lord High Treasurer and Treasurer of the Exchequer was the Duke of Shrewsbury from July to October 1714, after which the office was put into commission with the Earl of Halifax as First Lord of the Treasury. Walpole was made First Lord of the Treasury in October 1715 until April 1717, and after he returned to the post in April 1721, it was effectively the head of the ministry and prime minister.

If the Prime Minister is First Lord of the Treasury and the Chancellor of the Exchequer is Second Lord, who are the other holders of the office in commission? The remaining Lords Commissioners of the Treasury are government whips in the House of Commons, currently Sir Nic Dakin, Vicky Foxcroft, Taiwo Owatemi, Jeff Smith and Anna Turley. They are collectively and theoretically in charge of HM Treasury—for example, the Debt Management Office acts on behalf of the sovereign with the legal identity of The Lords Commissioners of HM Treasury—but in practice ministerial control is delegated to the Chancellor of the Exchequer and Second Lord and her team of six Treasury ministers. The tenure of those five whips as Lords Commissioners allows them to be paid a salary. In addition, the Government Chief Whip in the House of Commons, Sir Alan Campbell, is formally Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury, again to enable him to draw a ministerial salary, though he is neither a working Treasury minister nor one of the Lords Commissioners.

The Lords Commissioners, collectively known as the Treasury Board, originally met regularly to transact the business of the office which they shared. Until 1760, they met under the chairmanship of the King in person, with papers prepared and minutes kept by the Secretaries to the Treasury (who can today be traced to the junior Treasury ministers and the Chief Whip). George III, who succeeded to throne in 1760, no longer attended, and by the end of the 18th century the nation’s finances were becoming unmanageable by a board of this kind. The meetings became formalised, twice-weekly events, and in 1827 the First and Second Lords ceased to attend, with business being prepared beforehand for the notional sanction of the remaining Lords Commissioners. The Treasury Board stopped meeting in 1856 after a structural reorganisation and the Chancellor of the Exchequer took overall control of the Treasury’s business.

From 1709 to 1964, the political head of the Royal Navy—in effect the navy minister—was the First Lord of the Admiralty. This also resulted from an office being placed into commission, that of Lord High Admiral. It first happened in 1628 after the assassination of the Duke of Buckingham (he was stabbed to death at the Greyhound Inn in Portsmouth, which seems appropriate for the Lord High Admiral) and the Lord High Treasurer, Lord Weston of Nayland (later Earl of Portland), was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. There were six other Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty appointed, all of them occupying or soon to occupy other official posts: the Earl of Lindsey, Lord Great Chamberlain; the Earl of Dorset, Lord Chamberlain to the Queen; Sir Francis Cottington, who became Chancellor of the Exchequer six months later; Sir Henry Vane, shortly afterwards Comptroller of the Household; Secretary of State Sir John Coke; and Francis Windebank, Clerk of the Signet, who was knighted in 1632 and became a Secretary of State.

There was a Lord High Admiral again from 1638 to 1642, 1643 to 1646 and 1660 to 1679. From 1684 to 1689 the office was held by the monarch and the Admiralty Act 1690 provided for it regularly to be in commission. The commission was dissolved in 1701 and, after a few months in which the Earl of Pembroke held the position, Prince George, Duke of Cumberland, the husband of Queen Anne, was Lord High Admiral (though it was largely an honorary appointment). Prince George died in October 1708 and, after a few weeks during which the Queen and then the Earl of Pembroke were Lord High Admiral, the office was placed permanently in commission and the First Lord of the Admiralty became a regular appointment in what emerged as the cabinet. (There was a brief hiatus in 1827-28 when the Duke of Clarence and St Andrews, later King William IV, was Lord High Admiral.) The Admiralty Board abolished in 1964 when the three separate service ministries (the Admiralty, the War Office and the Air Ministry) were merged into the Ministry of Defence, and the title of Lord High Admiral reverted to the sovereign. The late Duke of Edinburgh served as Lord High Admiral from June 2011 till his death in April 2021, when it reverted once again to the Crown.

“What is written without effort is in general read without pleasure.” (Samuel Johnson)

“The Trouble with ‘Heart of Darkness’”: last week I recommended an episode of The Rest Is History’s four-part series on the Congo Free State which dealt with Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, and Dominic Sandbrook referred to this 1995 essay in The New Yorker by David Denby, so I went back and read it. It examines the way we view Conrad and his book in the post-colonial era, through the lens of a Literature Humanities course at Columbia University, looking at accusations of racism, white supremacy, near-genocide and whether Conrad was an imperialist. I will leave you to read the details, but suffice to say I have a great deal of sympathy for Denby’s argument that many of these questions are trite, unrevealing and rather boring, and miss the point of literature and its place in our cultural landscape (also a few swipes at Edward Said will never put me off reading anything).

“The Last Days of Eric Liddell”: for a lot of us, I suspect, Eric Liddell is largely the figure portrayed by the late, great Ian Charleson in Chariots of Fire (1981), a devoutly Christian Scotsman who refused to participate in the heats for the 100 metres, his strongest event, at the Paris Olympics in 1924 because they were held on a Sunday and he had strict Sabbatarian beliefs. Instead he contested and won the 400 metres, breaking Olympic and world records. In this article for The Critic, Bethel McGrew looks at Liddell through the overriding lens of his religion, his devotion to missionary work in China (he was born in Tientsin to parents who were missionaries) and his internment and death in a Japanese prison camp during the Second World War. He died in February 1945 of an undiagnosed brain tumour, aged 43, six months before the camp was liberated. McGrew portrays a wholly gentle and good man who was an inspiration to his fellow internees in some of the darkest days of the 20th century.

“Paddy Mayne: Lt Col Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne, 1 SAS Regiment”: the recent BBC drama SAS Rogue Heroes turned the spotlight on the early days of the Special Air Service and reopened the evergreen story of Blair “Paddy” Mayne and his supposedly being denied the award of a Victoria Cross, despite a recommendation towards the end of the Second World War. This tidily crafted biography by Hamish Ross presents a balanced picture of a complex man: a solicitor from Newtownards in County Down who played international rugby for Ireland and the British and Irish Lions, Mayne was recklessly brave, could be aggressive to the point of violence but had a solitary, contemplative and intellectual side. He won the Distinguished Service Order four times between 1942 and 1945 and commanded 1 SAS Regiment in France after D-Day, and found the transition back to civilian life and his legal career after the war difficult. He died in a car crash in December 1955, a few weeks short of his 41st birthday. Christened Robert Blair Mayne and from a family of prosperous Presbyterian merchants, he disliked the nickname “Paddy”.

“Pamela Harriman: an unsung hero of the Atlantic world”: in Engelsberg Ideas, biographer Sonia Purnell traces the career and influence of Pamela Harriman: born into the staid end of the English aristocracy, she was introduced to Hitler by Unity Mitford, married Randolph Churchill, fell in love (and would eventually marry) with American banker and diplomat Averell Harriman, married Hollywood agent Leland Hayward, had affairs with Edward R. Murrow, Prince Aly Khan, Gianni Agnelli and Baron Élie de Rothschild, helped the Democratic Party rebuild itself in the 1980s and served as US Ambassador to France under President Clinton from 1993 to 1997. It is a life so improbable that it can only be true, and Harriman used every tool at her disposal to wield influence. Was she manipulated by others, a cynical opportunist or a supreme pragmatist? That, I fear, you will have to decide.

“The North/South urban divide”: Jon Neale, Head of Research and Insight at property consultancy Montagu Evans, wrote a brilliant explanation of Britain’s urban culture and development, showing how different patterns of urbanisation in London compared to other cities has had a profound effect on what Britain looks like and how our society and economy work. London, along with one or two other cities in the South, have the most expensive and desirable property around the centre, whereas in most cities in the North and Midlands, inner city property is among the cheapest, while the suburbs are the most expensive places to live. This has to be considered alongside fundamental differences in density. He also makes a telling point about the economic dominance of London, the centralisation of the British economy and the issues which “levelling up” was designed to address—to a much greater degree than in other countries, this has always been the case in England. It has always been a country of “London then other cities”: shortly after the Norman Conquest of 1066, London had a population of around 17,000, far larger than Winchester (6,000), Norwich (4,445) and York (4,134). Every other city had a population under 4,000. A very revealing analysis of how we got to where we are.

“I grew up watching TV, and I don’t think I’m too dumb or too crazy.” (Jason Bateman)

“Oscar Winners: A Secrets of Cinema Special”: last week was, of course, the 97th Academy Awards ceremony, so the BBC showed a special episode of Mark Kermode’s Secrets of Cinema series in which he looked at nearly a century of prize-giving by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He examines the sort of films which are successful and why, what subjects are popular with Academy voters, how they can best be presented by film-makers, the changing trends in what the Academy rewards and some of the most significant winners. A bit of a gallop but an enjoyable broad-brush treatment of cinema history. And why not? as Barry Norman used to say (though it was a phrase his Spitting Image puppet used far more often than he ever did in real life).

“Training Day”: the BBC also happened to show this 2001 Denzel Washington/Ethan Hawke crime thriller which is always worth a watch. Hawke is an ambitious young LAPD detective and Washington a highly decorated veteran of the narcotics squad, and the film follows them on a single day as they navigate the gang-dominated areas of Westlake, Echo Park and South Central Los Angeles. On the face of it, the story is a typical depiction of the Jekyll-and-Hyde nature of police work: how far can you become your opponents to be effective in defeating them, and when have you lost your moral authority? The two stars are on sizzling form, with some excellent supporting performances by Tom Berenger, Scott Glenn, Eva Mendes, Snoop Dogg and Dr Dre. Denzel Washington was rewarded with the Academy Award for Best Actor and Hawke was nominated for Best Supporting Actor (losing out to Jim Broadbent for Iris). Quality film-making.

“Modern Wisdom: Rory Sutherland”: I am as ever unapologetic for recommending something else featuring Rory Sutherland, Vice-Chairman of Ogilvy Group and behavioural guru, this time an appearance on Chris Williamson’s Modern Wisdom podcast. As ever, this covers a huge amount of ground, with Rory’s acute and sometimes offbeat but always revealing observations on Jaguar’s change of marketing strategy, the future of working from home, Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign and internet cookies among other subjects. Just a joyous learning experience.

“Churchill’s Right Hand Man”: on the Aspects of History podcast, host Ollie Webb-Carter speaks to Lieutenant General Sir John Kiszely, former Director General of the Defence Academy about his recent biography of Hastings “Pug” Ismay, Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence then Winston Churchill’s chief staff officer, who acted as an invaluable conduit between the Prime Minister and the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Ismay went on to be the first Secretary General of NATO from 1952 to 1957. Churchill’s relationship with the military establishment during the Second World War was often stormy and tense, which could have put Ismay in an intolerable position, but his skills and personality allowed him smoothly and discreetly to help the system work. His role in Britain’s war effort was absolutely vital but is underappreciated, and Kiszely brings a thoughtful soldier’s eye to the story.

“imagine… The Academy of Armando”: Alan Yentob’s arts and culture BBC series profiles the satirist Armando Iannucci, from his mid-1990s big break creating The Day Today with Chris Morris to his current stage adaptation of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove. From a family of Italian immigrants in Glasgow, Iannucci read English at the University of Glasgow and started a DPhil at University College, Oxford, on religious language in 17th century literature with particular reference to John Milton’s Paradise Lost, leaving to pursue a career in comedy. It is a significant educational pedigree, sharing unfinished doctoral research in the comedy world with Alan Coren, David Baddiel, John Sessions, Ben Miller and Rowan Atkinson, and there has always been a cerebral, literate aspect to Iannucci’s work, sitting defiantly alongside brutal profanity. There is currently something of a centre-right backlash against Iannucci as an impeccable representative of the liberal élite, but for me the work speaks for itself: The Day Today, The Thick of It, Knowing Me Knowing You/I’m Alan Partridge/Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa/Mid Morning Matters and The Death of Stalin are all outstanding. Add in The Armando Iannucci Shows, Time Trumpet, Veep and The Personal History of David Copperfield and it adds up to a formidable corpus. It’s a matter of taste, ultimately, so, in the words of Malcolm Tucker, come the fuck in or fuck the fuck off…

Faithless is he…

… as Gimli, son of Glóin, observes to Elrond, master of Rivendell, that says farewell when the road darkens. Let us take that hold that in our minds and go about our business before we are drawn together again. This world may be a mad and frightening place at times, but I wouldn’t miss it for anything. L8ers.

What a rich captivating read . Thank you .

Another great read and afternoon of Wikipedia hopping. Loved the Rory Sutherland interview and am saving Mark Kermode for tomorrow.