Sunday round-up 6 October 2024

Birthday wishes to Melvyn Bragg, Elisabeth Shue and Emily Mortimer, and previously Barbara Castle, as the Church of England remembers William Tyndale

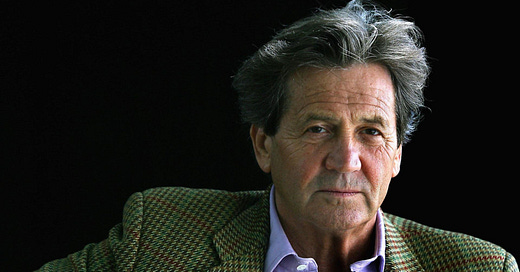

Today we’re pulling the party poppers and donning the paper hats for Coronation Street legend Eileen Derbyshire (93), journalist, writer, broadcaster and cultural barometer Lord Bragg (85), actress and singer Britt Ekland (82), Gulf war 1 hero Major General Patrick Cordingley (80), former president of Sinn Féin and not-a-nice-man Gerry Adams (76), author and journalist Penny Junor (75), Zimbabwean goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar (67), filmmaker, presenter and one-time punk singer Richard Jobson (64), former Stonewall chief executive Ben Summerskill (63), actress Elisabeth Shue (61), actress and filmmaker Emily Mortimer (53), former champion boxer Ricky Hatton (46) and versatile Japanese racing driver Hideki Mutoh (42).

Stuffing their faces with cake in yesteryear are Jesuit missionary to China Matteo Ricci (1552), first female Methodist preacher Sarah Crosby (1729), Scottish-Canadian businessman and founder of eponymous Montreal-based university James McGill (1744), penultimate French monarch and “Citizen King” Louis Philippe I (1773), “Swedish Nightingale” Jenny Lind (1820), architect and painter Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret) (1887), fearsome Labour Party icon Barbara Castle (1910), ethnographer, explorer and balls-of-steel flimsy raft enthusiast Thor Heyerdahl (1914), director, playwright and “Mother of Modern Theatre” Joan Littlewood (1914), dictator, dynast and president of Syria Hafez al-Assad (1930), cricketer and broadcaster Richie Benaud (1930) and German racing driver Manfred Winkelhock (1951).

Today in 1600, the Palazzo Pitti in Florence hosted the first performance of Jacopo Peri’s Euridice. It is the oldest surviving opera, as Peri’s Dafne of 1598 is lost. Telling the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, it established some of the fundamental elements of opera such as the use of aria and recitative and the combination of solo, ensemble and choral singing. It was composed in honour of the marriage of King Henri IV of France and Maria de’ Medici, daughter of Grand Duke Francesco I of Tuscany.

On this date in 1854, a fire was discovered at the worsted mill of Messrs J. Wilson and Sons on the south bank of the River Tyne in Gateshead. The factory was only three years old, having replaced another mill which had burned down, but being gaslit and housing a large amount of oil which was used to treat wool, it was perfect kindling and by 1.30 am the fire was out of control. The heat of the fire caused an explosion in a neighbouring bond warehouse owned by Charles Bertram which contained thousands of tons of sulphur and nitrate of soda. The flames began to spread, including to a jetty used for loading coal, and there were two more explosions in the Bertram warehouse. At 3.10 am there was a fourth, catastrophic explosion which was heard 20 miles away, devastating the quayside, lifting boats out of the river and destroying St Mary’s Church on the hill in Gateshead. Debris was thrown as far as three-quarters of a mile, and the resulting crater was 40 feet deep and 50 feet wide. Burning debris started a fire on the other side of the river in Newcastle, and the flames burned throughout the day, destroying most of the buildings on both sides of the river. There were 53 deaths and 400-500 people injured.

In 1903, this day saw the first sitting of the High Court of Australia. A national court had first been mooted by the Privy Council in 1849, and in 1856 the governor of South Australia, Richard MacDonnell, suggested to the provincial government in Adelaide that a judicial body be established to hear appeals from the supreme courts of each of the colonies (South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania). Only the Victorian government showed any enthusiasm, and in 1870 it established a royal commission to examine the proposal. When its draft bill anticipated a system which did not provide for appeals to the Privy Council, it was effectively vetoed by the British government. Eventually, a new scheme was submitted to London in 1899, and a compromise was negotiated whereby appeals to the Privy Council were in general allowed but the Parliament of Australia, which was about to be created, would have the power to restrict such appeals. Eventually, on 25 August 1903, the Judiciary Act 1903 received Royal Assent and the three-member court was established. The first justices, appointed on 5 October, were Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith, previously premier then chief justice of Queensland; Sir Edmund Barton, who stepped down as the first prime minister of Australia to take up the appointment; and former New South Wales senator Richard O’Connor. The inaugural session was held in the Banco Court of the Supreme Court of Victoria in Melbourne.

Today is the feast of St Bruno (1030-1101), founder of the Carthusian Order. We aso remember St Sagar of Laodicea (d AD 175), an early martyr who was supposedly a disciple of St Paul; St Faith of Conques, a shadowy figure of the 3rd or 4th century AD who was tortured to death with a red-hot brazier in southern France and is the patroness of pilgrims, prisoners and soldiers; and St Pardulphus (AD 657-AD 737), a Benedictine monk from central France who became abbot of Guéret. The Anglican Communion commemorates William Tyndale (1494-1536), the Protestant scholar who translated much of the Bible into English working directly from Greek and Hebrew texts and was executed for heresy in the Habsburg Netherlands.

The United States is observing German-American Day, marking the foundation of Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1683 and celebrating German-American heritage. In Hungary it is Memorial Day for the Martyrs of Arad, remembering the execution of 13 Hungarian generals in 1849 for supporting Lajos Kossuth’s independence movement against the Habsburg monarchy. Sri Lanka is celebrating Teachers’ Day, which is fairly self-explanatory.

In the United Kingdom, today is National Badger Day, part of #Brocktober 2024 (see what they did there?).

For American readers, it is National Noodle Day and National Plus Size Appreciation Day. I’m just saying.

Factoids

Having previously held the post from 2012 to 2017, Mike Nesbitt has resumed the leadership of the Ulster Unionist Party. He was the first UUP leader to be a graduate of the University of Cambridge (the only other has been Steve Aiken, 2019-21) and the only one to be educated at Campbell College, Belfast, renowned for educating the “cream of Ulster” (detractors: “rich and thick”).

None of the Democratic Unionist Party’s six leaders attended a British university (although the Rev Ian Paisley studied at Barry School of Evangelism in South Wales). Lord Dodds of Duncairn, deputy leader 2008-21, read law at St John’s College, Cambridge, while the party’s founding chairman (1971-73), Desmond Boal QC, had studied at Trinity College Dublin.

The current border between Northern Ireland and Ireland was supposed to be a temporary demarcation. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 established two devolved jurisdictions within the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, the former consisting of the six north-eastern counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone. Southern Ireland, comprising the remaining 26 counties, rapidly became independent as the Free State, and the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 provided for a boundary commission to draw a final border between the two polities. Appointed in 1924, the commission was chaired by South African lawyer Richard Feetham (appointed by the British government), the Free State nominated its minister of education, Eoin MacNeill, and Belfast barrister and newspaper editor Joseph R. Fisher was appointed by London to represent the Northern Ireland government. By November 1925, the Boundary Commission had prepared its recommendations, but they were leaked to The Morning Post and in the ensuing controversy Belfast and Dublin agreed to set the matter aside and continue with the existing border. The Boundary Commission’s report was eventually released in 1969 but never implemented.

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 provided for a whole superstructure of administration for Southern Ireland as well as Northern Ireland which were virtually stillborn, overtaken by the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the independence of the Irish Free State. The Parliament of Southern Ireland met formally only once, on 28 June 1921; it consisted of a House of Commons with 128 seats (120 from multi-member county and borough constituencies, four elected by graduates of Trinity College Dublin and four representing the National University of Ireland); and a Senate with 64 members which included the Lord Chancellor of Ireland as presiding officer, four Catholic bishops or archbishops, four Church of Ireland bishops or archbishops and 16 peers. The Parliament was never fully constituted, since at the May 1921 election all the county and borough constituencies and the National University of Ireland returned Sinn Féin candidates unopposed, who did not attend but assembled as the Second Dáil, while the Catholic Church, the county councils and the labour movement all boycotted the Senate. The two Houses met in the Royal College of Science for Ireland on Merrion Street with only four Unionist MPs for Trinity College Dublin as the House of Commons and 15 senators, and the State Opening was conducted by the Lord Lieutenant, Viscount FitzAlan of Derwent. The House of Commons afterwards adjourned sine die while the Senate met once more, on 13 July. The Parliament of Southern Ireland was formally dissolved by the Lord Lieutenant on 27 May 1922.

The Senate was a motley assortment at the State Opening. The Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir John Ross, a former Conservative MP and judge in the Chancery Division of the High Court of Justice in Ireland, was too ill to attend so Sir Nugent Everard, a Unionist appointed to represent commerce, acted as chairman. There were three other representatives of commerce; five of the professions, H.P. Glenn, former moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Ireland representing commerce or the professions; Dr John Gregg, Archbishop of Dublin in the Church of Ireland; General Sir Bryan Mahon, former Commander-in-Chief, Ireland, elected from the Privy Council of Ireland; and three peers, Lord Cloncurry, Lord Rathdonnell and the Marquess of Sligo. Four senators not present at the State Opening attended the second meeting on 13 July: Ross, the Lord Chancellor; Colonel George O’Callaghan-Westropp, nominated to represent commerce or the professions; Sir John Moore, former president of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, for the professions; and Walter MacMurrough Kavanagh, former Nationalist MP, elected from the Privy Council.

Today in 1903 was the first sitting of the High Court of Australia (see above). Two of the justices, Sir Edmund Barton and Richard O’Connor, were born in the same suburb of Sydney, Glebe, were friends from childhood and O’Connor would serve as leader of the government in the Senate when Barton was prime minister from 1901 to 1903. The chief justice, Sir Samuel Griffith, however, was from Merthyr Tydfil in Glamorgan, emigrating to New South Wales with his family when he was eight years old. All three were graduates of the University of Sydney (although until 1874 it was one of only two universities in Australia, along with the University of Melbourne).

In 1937, the University of Sydney appointed a new professor of Greek, a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, was who was only 25 years old, John Enoch Powell. He had won most of the major prizes at Cambridge, and the eminent classicist Martin Charlesworth, president of St John’s College, described him as “the best Greek scholar since [Richard] Porson”. Powell was primarily a philologist and textual critic, with particular expertise on Herodotus, and his intensity was not to everyone’s taste. One of his students at Sydney, future prime minister of Australia Gough Whitlam, damned his lectures as “dry as dust”. Although Powell was extraordinarily young to hold a chair and was the youngest professor in the Commonwealth, he was disappointed not to have matched or beaten the achievement of his then-hero Friedrich Nietzsche, who had been appointed professor of classical philology at the University of Basel aged 24.

Powell’s stay in Sydney was short. In 1938/39, he travelled back to England and was appointed professor of Greek and classical literature at the University of Durham, the post beginning in January 1940. He returned to his academic duties in Australia, but came back to England when war was declared in September 1939. A few weeks after his arrival, he enlisted as a private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, but had to pretend to be Australian to be accepted, as at that stage the War Office had more volunteers than it needed. Australians, on the assumption they had expended a great deal of money and effort to make the journey to Britain, were accepted straight away. Powell’s appointment to Durham was deferred, and eventually cancelled. He would never return to academia.

Powell did not remain a private for long, either. He was quickly promoted to lance-corporal, which he would later say was a greater step than joining the cabinet, and then early in 1940 he was working in a kitchen during a visit by a brigadier, whose question he answered with an ancient Greek proverb. It was enough to have him selected for officer training, and he was commissioned in May 1940, joining the Intelligence Corps. He was promoted again and again until in 1944 he became the youngest brigadier in the British Army.

Only one other man went from private to brigadier in the Second World War, Powell’s fellow Conservative MP Sir Fitzroy Maclean. He had been prevented from joining the army at the outbreak of war because he was a second secretary at the Foreign Office and therefore in a reserved occupation. He responded by resigning from the Diplomatic Service “to go into politics”, then took a taxi to the nearest recruiting office and enlisted as a private in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. Like Powell he was quickly promoted to lance-corporal, then commissioned in 1941. In 1943, he was made a brigadier and head of the British mission to the Yugoslav partisans headed by Tito. In August 1941, the Conservative MP for Lancaster, Herwald Ramsbotham, was ennobled as Lord Soulbury, and Maclean, having cited politics as his reason for leaving the Diplomatic Service, was elected as the new Conservative MP against two independent candidates. He remained the Member for Lancaster until 1959, when he relocated to Bute and North Ayrshire before retiring at the February 1974 general election. Powell stood down as Conservative MP for Wolverhampton South West at the same time, but returned as an Ulster Unionist for South Down in October 1974 and retained the seat until 1987.

“Television! Teacher, mother, secret lover.” (Homer Simpson)

“Storyville: War Game”: a fascinating if curious “documentary thriller” which shows an exercise organised by Vet Voice Foundation. A group of bipartisan defence and intelligence officials and elected policymakers are presented with a scenario similar to the assault on the United States Capitol on 6 January 2021, but with better organised insurgents and the collusion of some law enforcement personnel. Led by a fictional President-elect John Hotham (former Democratic governor of Montana Steve Bullock), they are presented with pre-recorded news footage and unfolding internet reaction and have to decide how to respond to and attempt to control the situation. Gripping but unnerving, as their confusion, uncertainty and growing horror is palpable. There really are no easy decisions.

“Boris Johnson: The Interview”: ITV’s Tom Bradby managed to avoid Laura Kuenssberg’s mistake of sending her notes to the subject of the interview, and sat down with the former prime minister as he promotes his memoirs, Unleashed, which will be published on Thursday 10 October. (I wrote about prime ministerial recollections in CulturAll this week.) There are few surprises in this. Johnson is bullish and unrepentant, insisting that he was brought down by events and by a conspiracy of colleagues and enemies, and that he would have won the recent general election. Anyone who has read Nadine Dorries’s recent conspiracy shriek The Plot: The Shocking Inside Story of Who Really Runs Britain will recognise the outline of Johnson’s thesis, which is largely spurious and self-exculpatory. Many suggested there was no point in watching this interview, and certainly its subject is short on self-reflection or contrition, but it is interesting to see the full sweep of narrative of “alternative facts”, to borrow from Kellyanne Conway. It confirms and emphasises that the former prime minister is a solipsistic narcissist with a dizzying indifference to the truth, and, although it seems an unlikely prospect, his ego would clearly drive him to leap at the chance of a political comeback.

“Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens”: with Robert Eggers’s remake of the vampire classic being released on Christmas Day in the United States (3 January 2025 in the UK), I wrote an article for CulturAll (still in the works) about the scale of the challenge Eggers is taking on. This led me inevitably back to F.W. Murnau’s groundbreaking 1922 original starring Max Schreck as a thinly veiled version of Dracula. The makers of Nosferatu failed to seek permission from Bram Stoker’s estate, his widow sued for breach of copyright and a German court ordered the studio to pay compensation and surrendered all negatives and prints of the film; thankfully a few which had been sent abroad survived. It is a vivid, startling, revolutionary and genuinely horrifying film, steeped in German Expressionism and unsettling on a very visceral level. If you have never seen it, watch it now. If you have, watch it again. Are there antisemitic overtones? Arguably, though Murnau himself was not notably prejudiced against Jews as far as we know, and as a homosexual knew something of the life of the outsider in society. It is just a remarkable piece of cinema history. The remake will have to deliver a lot to be worthy.

“Why is Britain poor?”: a brilliantly sparky and imaginative conversation from Spectator TV with the magazine’s economics editor Kate Andrews (a fellow St Andrews graduate) interviewing Ogilvy UK vice-chairman and behavioural science guru Rory Sutherland about the development of the modern workplace and economy, exploring some of the fundamental weaknesses which seem to plague the United Kingdom in particular. Even if you don’t agree with all of the propositions offered, I genuinely don’t think time listening to Rory is ever wasted: at the very least you will be provoked into thinking about the world in new and revealing ways. There is a distinct air of national malaise which is challenging but I have no doubt we can find ways out; looking for them, however, is going to be hard work.

“Strike: An Uncivil War”: I’m just catching up with Daniel Gordon’s documentary, available on Netflix, chronicling the so-called Battle of Orgreave, a confrontation between striking miners and police officers, mainly from South Yorkshire Police, at British Steel’s coking plant at Orgreave near Rotherham. The miners’ strike of 40 years ago was a monumental collision between organised labour and a government, and particularly a prime minister, determined to assert authority in a time of industrial action. At the time, Orgreave was depicted as unacceptable violence by pickets against police, but there is considerable evidence that the forces of law and order were not only prepared but eager for a violent showdown. A skilful chronicle and powerful reminder of a brutal time which defies easy categorisation.

“I write because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing.” (George Orwell)

“Has the UK Supreme Court been a success?”: Tuesday marked the 15th anniversary of the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court assuming the judicial functions of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords to achieve, it was intended, greater separation of powers. In The Spectator, my friend and former colleague Alexander Horne looks back at the new body’s existence and operation. The establishment of the court was slow, clumsy and poorly planned, and it created fears of increasing judicial activism and conflict with the legislature. All told, however, Alex takes the view that the court is now stepping away from overtly political issues, especially under its current president Lord Reed of Allermuir, and the legal and intellectual calibre of the justices has remained high. Perhaps, though, it has not really done very much differently from the House of Lords in its judicial function, which does prompt the question: what was it all for?

“A language of beautiful impurity”: another piece from Ed West’s Substack, The Wrong Side of History, examines the enormous effect the Norman Conquest and the imposition of a form of French had on the English language. He starts by imagining what English might be like without this continental shaping: no use of the “gh” and no letter “q”, although my favourite suggestion was that the Ministry of Defence would be the Shieldness Thaneship. Ed argues that there is an “emotional, atavistic appeal” to Anglo-Saxon words but concludes that he is grateful for the richness and linguistic diversity of modern English.

“All change on the Overground”: another Substack entry, from Jonn Elledge’s The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything. He examines what may seem an obscure topic, namely how the transformation of London Overground into six separate lines (Liberty, Lioness, Mildmay, Suffragette, Weaver and Windrush) will be depicted on Transport for London’s signage. Niche, you might think, but, if you’re a Londoner, think how often you use the Tube, how often you look at a Tube map, and how much of its design you take for granted. The first iteration of the Tube map was, of course, designed in 1931 by Harry Beck, a draughtsman who had the revolutionary realisation that the London Underground did not need to be represented as a geographical map, tied to the landscape above ground, but could be radically simplified and clarified into a schematic which showed the relationship between stations and lines. In nearly 100 years, however, a great deal more information has been added to the map, and Jonn explains the (sometimes unlikely) considerations that apply to redesigning it.

“America Is Lying to Itself About the Cost of Disasters”: in the wake of Hurricane Helene, Zoë Schlanger in The Atlantic examines the resources of the United States for disaster management and recovery. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is struggling for budget and if there is another hurricane or a disaster of a similar scale, it will run out of money. Essentially she argues that the cost of repeated emergencies is far in excess of the resources the federal government has allowed for them, and the mismatch is getting worse. Disasters are becoming more frequent and more severe, and insurers are beginning to withdraw from some areas or raise premiums to unaffordable levels. Inadequate financial capacity means there is no scope to upgrade and protect infrastructure against future events, so the federal government is only able to be reactive. Resilience is a neglected and unglamorous subject but it is vital to keep societies going. Yet, as Schlanger observes, America has yet to reach a tipping point at which it realises the scale of the problem.

“Iran is on the verge of a nervous breakdown: can the regime hold?”: an absorbing essay by Roger Boyes from The Times yesterday which examines the condition of the Islamic Republic of Iran and suggests it is a régime facing crisis. The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is 85 years old and there have been several rumours of ill-health including cancer, while the last president, Ebrahim Raisi, was killed in a helicopter crash in May. His successor, Masoud Pezeshkian, a 70-year-old former cardiac surgeon, is said to be a moderate (in the context of Iranian politics) and has urged caution on Khamenei as hostilities with Israel have intensified. Boyes highlights the extraordinary penetration of Hezbollah that Israel has achieved, wiping out its senior leadership cadre, and reminds us that terror groups across the Middle East have now been reduced to relying on couriers rather than electronic communication which can be intercepted and monitored. He also argues that Iran’s network of proxy militant groups across the region is deteriorating and has failed to act in a co-ordinated way against Israel and the West, while domestic dissent in Iran is growing and the economy is floundering. Has the Islamic Republic reached the end of the road? How does this end?

With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion…

… in the words of Robert E. Lee, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration for myself, I bid you an affectionate farewell. Toodles.