Sunday round-up 6 April 2025

Birthdays include Roger Cook, John Ratzenberger and Rory Bremner, and it's Tartan Day, Waltzing Matilda Day and the feast of St Marcellinus of Carthage

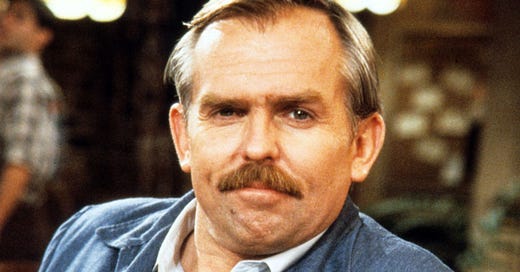

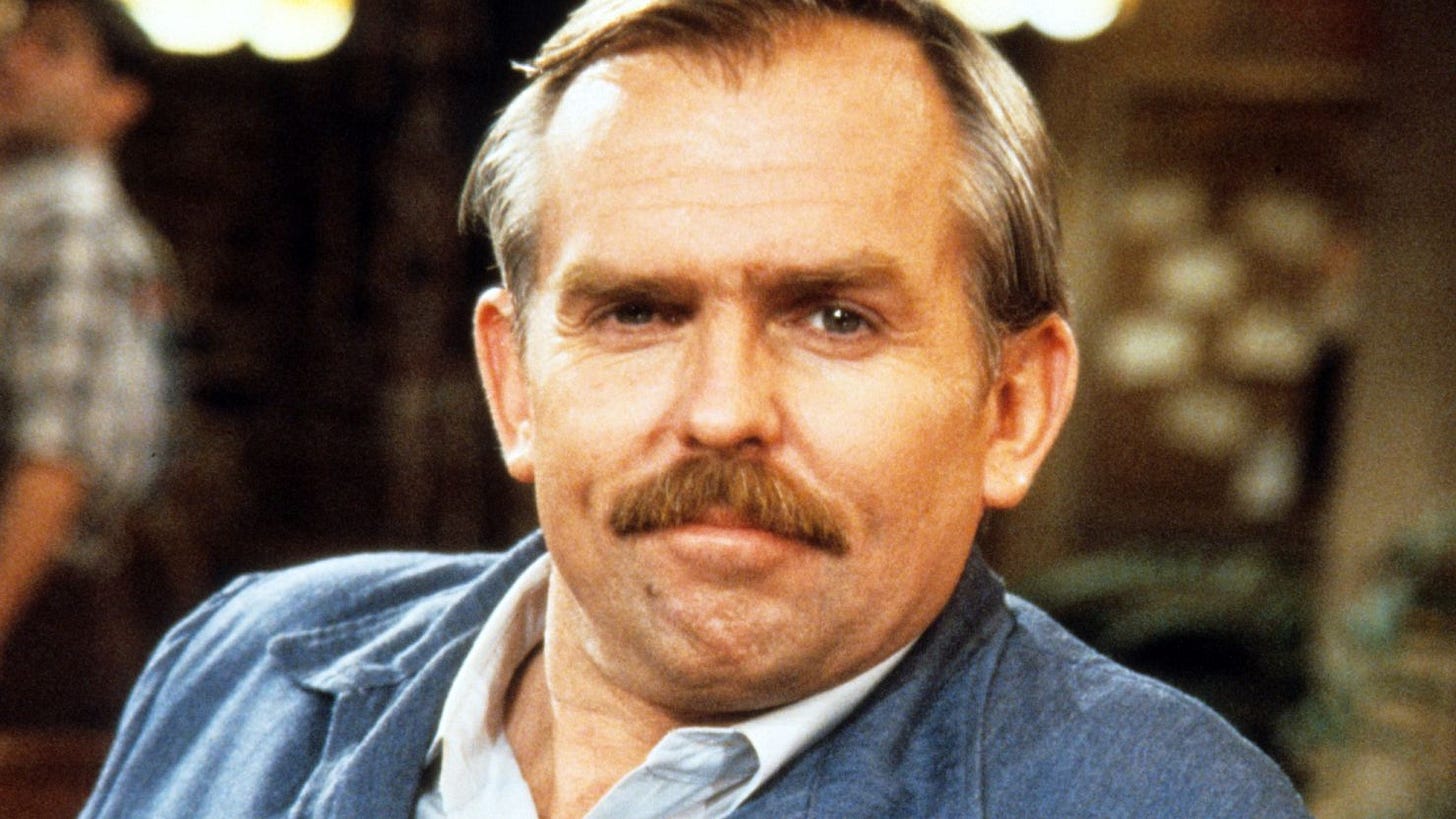

Ticking off another year and feigning gratitude for unwanted socks and celebrity autobiographies today are pioneering geneticist and occasional dabbler in “I’m not a racist but…” studies James Wilson (97), commercial law guru Professor Sir Roy Goode (92), actor, singer, painter, novelist and Star Wars notable Billy Dee Williams (88), actor, director, producer and screenwriter Barry Levinson (82), yeah-I-thought-he-was-dead-too investigative journalist and broadcaster Roger Cook (82), former Conservative MP, leader of Wandsworth Borough Council and dentist Sir Paul Beresford (79), actor and Cheers stalwart John Ratzenberger (78), actress and author Marilu Henner (73), Tangerine Dream drummer Christopher Franke (72), endlessly affable former Conservative MP Lee Scott (69), impressionist and comedian Rory Bremner (64), Governor of Minnesota and Democratic vice-presidential candidate Tim Walz (61), versatile actor Paul Rudd (56), musician, singer, presenter, model and Hear’Say alumna Myleene Klass (47) and journalist, financier and Big Suze-marrying mid-grid royal Lord Frederick Windsor (46).

Those who didn’t quite make it but used a love a good old knees-up (that may not be universally true) include Jewish philosopher and Torah scholar Maimonides (1135), playwright, poet, epigrammist and very much not the author of Du contrat social Jean-Baptiste Rousseau (1671), historian, economist, political theorist, philosopher and John Stuart’s dad James Mill (1773), sculptor and jewellery designer René Lalique (1860), last Nizam of Hyderabad and possessor of improbable wealth Mir Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII (1886), businessman and aeronautical engineer Anthony Fokker (1890), third Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and distressingly willing wartime producer of antisemitic propaganda Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1904), versatile motor racing virtuoso Hermann Lang (1909), painter and author Leonora Carrington (1917), former First Minister of Northern Ireland, veteran Antrim MP and shunner of all things papal Ian Paisley, Lord Bannside (1926), pianist, composer and conductor playing all the right notes in the right order André Previn (1929), singer-songwriter and country music icon Merle Haggard (1937), magician and television host Paul Daniels (1938), model and actress Anita Pallenberg (1942), journalist, publicist and serial sex offender Max Clifford (1943), trades union general secretary Rodney Bickerstaffe (1945) and disappearing-presumed-murdered basketball player Bison Dele (1969).

What’s in a name?

Today in 1793, there was an important organisational development in Revolutionary France. The monarchy had been abolished the previous September and the French Republic declared, with the National Convention acting as a provisional government. With 789 deputies in theory entitled to attend, it clearly could not be an executive in its full form; after King Louis XVI was executed in January 1793 and war broke out on several fronts, the Convention formed a Committee of General Defence consisting of 25 of its members to assume military leadership of France.

Soon it was decided that a still smaller body was needed, and on 6 April 1793 the National Convention established the Committee of Public Safety, a group of nine men with wide powers including the governance of the war and the appointment of generals, the selection of judges and juries for the Revolutionary Tribunal, the maintenance of public order and oversight of the state bureaucracy. It was initially dominated by Georges Danton, but when it was reconstructed in July, he ceased to be a member, while a 35-year-old lawyer from Arras was added to it: the radical Jacobin Maximilien Robespierre.

The Committee of Public Safety was also responsible for interpreting and implementing the decrees of the National Convention. From the summer of 1793 it oversaw a harsher and more repressive régime, eventually dubbed the Reign of Terror, as it feared an overwhelming combination of external enemies and internal traitors. Over the following 12 months, some 300,000 people would be arrested, 16,594 death sentences passed, another 10,000 to 12,000 executions without trial carried out and perhaps 10,000 would die in prison. The Terror is reckoned to have ended with Robespierre’s execution as a would-be dictator on 28 July 1794, but the Committee lasted, its influence much diminished, until the National Convention was disbanded in October 1795.

Are you still here???

On this day in 1984, there was an attempted coup d’état in Cameroon. Eighteen months earlier, in November 1982, Ahmadou Ahidjo, the country’s first president since independence from France in 1960, had stepped down for health reasons. He may have intended it only to be a temporary absence, and he stayed on as President of the Cameroon National Union, the ruling party, but the Prime Minister, Paul Biya, became President, and after a few months’ peaceful co-existence, a feud developed between the two. In July 1983, Ahidjo left for exile in France and Biya set about marginalising or eliminating his supporters, as well as removing official photographs of the former President and deleting his name from the national anthem.

In August 1983, Biya announced that a plot against him, sponsored by Ahidjo, had been uncovered and in February 1984 the former President was sentenced to death in absentia, although Biya commuted this to life imprisonment. Ahidjo denied any involvement in a plot but now freely denounced his successor as a threat to the unity of the state. At the beginning of April, Biya suddenly ordered the transfer away from the capital, Yaoundé, of all presidential palace guards who originated in the Muslim north of Cameroon, from where Ahidjo came (Biya was born in the Christian south, in the village of Mvomeka’a). He may have been informed that a plot was being coordinated by the presidential guards; at any rate, those ordered to be relocated instead rebelled against Biya, leading to several days’ heavy fighting in the capital.

Biya retained the loyalty of the air force, and eventually the rebels were defeated, with 1,000 of their number arrested and 35 immediately executed. He remains in office as President of Cameroon, having recently celebrated his 92nd birthday. After 42 years, he is the second-longest ruling president in Africa, after Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, who took power three weeks before Biya.

Lord and saints preserve us

A thin day hagiographically. It is the feast of St Sixtus I (d AD 126/128), the sixth Pope after St Peter, who decreed that only the clergy could touch the sacred vessels and that the priest should recite the Sanctus with the congregation after the Preface of the Mass; and of St Marcellinus of Carthage (d AD 413), tribune and notary of the Western Roman Empire and friend of St Augustine of Hippo, who presided over the Council of Carthage in AD 411, denounced as heretics and persecuted the Donatists but was arrested, tried and convicted for participating in the rebellion of Heraclianus and executed along with his brother Apringius, proconsul for Africa.

In the United States and Canada, it is Tartan Day, which is pretty much exactly what you think it is, commemorating the date of the signing of the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. For Australian readers, it is Waltzing Matilda Day, which is jolly.

It is International Asexuality Day, but that just doesn’t do it for me, I’m afraid.

Factoids

The first Academy Awards were presented on 16 May 1929 at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel in Los Angeles, two years after the establishment of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. There were 12 categories of award, covering films from the period of 1 August 1927 to 31 July 1928, and the results were announced three months before the formal ceremony, which itself only lasted 15 minutes. It was the only Oscars ceremony not to be broadcast on radio or television, as the second annual event in April 1930 was carried by local Los Angeles radio station KNX. The actor, producer, writer and director Douglas Fairbanks, one of the founders of the Academy and its first President, acted as the host.

One of the categories for which an Oscar was awarded only at the first ceremony was the Academy Award for Best Writing (Title Writing), which applied to the intertitles between scenes in silent films. This was a very distinct discipline, requiring the ability to convey large amounts of plot and contextual information in a few easily and quickly digestible sentences, and was given in 1929 to Joseph W. Farnham. The first iteration of the rules did not require nominees to be proposed for a specific film, and during the period of eligibility Farnham had written title cards for The Fair Co-Ed, London After Midnight, Spoilers of the West and West Point in 1927 and The Latest from Paris, The Crowd, The Trail of ’98, The Big City, Across to Singapore, Laugh, Clown, Laugh, The Actress, Diamond Handcuffs and Telling the World in 1928. But it was a category with a limited future: the release of The Jazz Singer starring Al Jolson in 1927, although only 15 minutes its one-and-a-half-hour running time was made up of singing and dialogue, showed that fully fledged “talkies” were going to become dominant. The award was discontinued after its first year, and silent films were all but obsolete by the end of 1929.

One of the points I sometimes labour to friends before they edge away gradually but politely is that Hansard (strictly the Official Report), the record of what is said in Parliament, is not quite a verbatim transcription of what MPs and peers say. If it were, as anyone who has used transcription software and seen an absolutely exact record will attest, it would be nigh-on unreadable. Even in a formalised setting like Parliament, we don’t speak in crisp, well constructed sentences without repetition or hesitation. We have verbal tics, we rephrase things, we change course in the middle of our thoughts. Hansard reporters are very skilled: they don’t edit heavily, but simply aim to produce an intelligible, ‘clean’ record of speeches and questions, in essence transcribing what MPs and peers meant to say. Nor will they edit out errors of fact: substantive corrections must be made separately and indicated as corrections. It is a great art, and one for which most parliamentarians are very grateful.

A good example of their craft appeared in a Twitter thread by Tides of History on Friday. On 4 April 1938, there were questions on the Order Paper for the Foreign Office, at that point only represented in the House of Commons by the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Rab Butler; Viscount Halifax had been appointed Foreign Secretary six weeks beforehand on the resignation of Anthony Eden. The first questions concerned events in Spain, where the civil war was still underway, although the Nationalists of Generalísimo Francisco Franco by then had the upper hand and had launched a major offensive in Aragón at the beginning of March. Butler, an emollient but evasive and elliptical man who always seemed to be saying less than he could, was not wholly forthcoming in his replies. He was pressed on what degree of formal recognition the government had accorded the Duke of Alba, Franco’s representative in London, George Ridley (Lab, Clay Cross) and George Strauss (Lab, Lambeth North) asking about driving licences, fees and waivers. Butler explained that some “privileges… of a limited character” had been afforded to the Duke and his staff but it did not represent diplomatic recognition, and added “I trust that the hon. Member will realise that the answer which I have just read out will allay some of the anxieties which he has expressed”. Clement Attlee, the Leader of the Opposition, argued that the Foreign Office had effectively recognised Alba, to which Butler countered that “the views taken in the Foreign Office are those which I have just read out”. Frustration at Butler’s evasion was growing and eventually Manny Shinwell, the Glasgow-raised Labour MP for Seaham, could no longer contain himself, at which point the Twitter thread takes up the story…

Most of the reports of the encounter describe Shinwell’s blow as an open-handed slap, which may well have been the case. But he caught Bower on the ear and caused internal bleeding between the layers of his left eardrum, not discovered until four days later. This in turn resulted in a blood clot which then burst Bower’s eardrum, and two weeks after event Bower was reported in TIME magazine to be “in a serious condition”. Clearly it was not a fatal blow, as Bower lived until 1975 and was 81 when he died. That, however, was nothing compared to Shinwell, who died in 1986, aged 101.

Luciana Berger, recently ennobled as Baroness Berger but before that Labour MP for Liverpool Wavertee from 2010 to 2019 and in her final year a member of The Independent Group and Change UK before sitting as a genuine independent, is Manny Shinwell’s great-niece.

While Hansard seeks to make speeches and interventions intelligible to the reader, sometimes the reporters push the boat out and indulge in a degree of creative licence. On 6 July 1978, the Commons was considering Lords Amendments to the Scotland Bill, and that inveterate scrutineer of all matters devolution-related, Tam Dalyell (Lab, West Lothian), had raised a point of order with the Speaker. At that moment, a few minutes after 4.00 pm, a number of protestors in the public gallery decanted three bags of horse manure which they had smuggled in under their clothing on to the benches below them. One of the protestors was 26-year-old Yana Mintoff, daughter of Dom Mintoff, the Prime Minister of Malta, and they objected to the presence of British soldiers in Northern Ireland. As they were taken away by security, the Speaker, George Thomas, rose to deal with the situation, as there was now a substantial amount of manure on the benches and floor, at which point all other Members should resume their seats. According to Hansard, Dalyell apologised: “I cannot sit down as I should when you rise, Mr Speaker, because the Bench has been soiled by some of the offensive matter that has just been thrown from the Public Gallery”. The sound recording reveals he said nothing of the sort. It may be one of Hansard’s most expansive explanatory glosses.

President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea and President Paul Biya of Cameroon (see above) are the longest serving current non-royal heads of state. Top of the leaderboard is the Sultan of Brunei, Hassanal Bolkiah, who ascended to the throne on the abdication of his father in October 1967. King Carl XVI Gustaf has reigned in Sweden since September 1973, making him the country’s longest serving monarch, and Ntfombi was Queen Regent of Swaziland from March 1983 to April 1986 before becoming Queen Mother and co-ruler with her son, King Mswati III. The King (iNgwenyama or “Lion”) and the Queen Mother (iNdlovukati or “She-Elephant”) are joint heads of Africa’s last remaining absolute monarchy. In 2018, Swaziland was renamed the Kingdom of Eswatini, meaning “Land of the Swazis” in Swazi.

Of the 20 longest serving current heads of state in the world, 10 are African, five European, three Middle Eastern, one central Asian and one Far Eastern. The 21st longest serving is President Vladimir Putin of the Russian Federation.

The longest rule ever is hard to establish, though a strong contender is King Min Hti of Launggyet in modern-day Burma; he acceded to the throne in around 1279, aged nine, and according to chroniclers reigned for 106 (though one British colonial historian, G.E. Harvey, in his 1925 History of Burma estimated it to have been “only” 95 years). Another possibility is Pharaoh Pepi II Neferkare who became ruler of Old Kingdom Egypt in about 2278 BC at the age of six and supposedly reigned for over 90 years. The longest verified reign of any monarchy was Sobhuza II, King of Swaziland from 1899 to 1982. He became ruler when he was four-and-a-half months old and his father, Ngwane V, died suddenly while dancing incwala, the summer solstice ritual of Swaziland.

“I try to keep it simple: tell the damned story.” (Tom Clancy)

“Even without the tariffs, Trump’s economic agenda is a disaster”: the elegant, erudite, sometimes caustic George F. Will, writing in The Washington Post, is as scathing as you would expect a traditional Republican to be about President Trump’s recently unveiled tariff scheme (“This. Will. Not. End. Well.”). Here, however, he sets it in the context of much broader economic delusion and mismanagement: Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid consume a tenth of the United States’s GDP, the national debt stands at 122 per cent of GDP and the Congressional Budget Office predicts it will rise to 156 per cent by 2055. Meanwhile Trump casually muses on scrapping (all?) taxes for those earning less that $150,000 (97 per cent of Americans), despite having promised with a straight face in 2017 to eliminate the national debt within eight years. In fact it grew by $8 trillion in four years. Yet there is no reflection, and certainly no embarrassment. It is a collection of ill-informed impulses which do not even make sense on their own terms.

“American Foreign Economic Policy Is Being Run By the Dumbest Motherfuckers Alive”: less measured than George Will but fuelled by a bracingly electric sense of fury is Daniel Drezner’s Substack, Drezner’s World. He argues that terrifying and unwitting incompetence in Washington will effectively withdraw the United States from global trade networks, but might well leave other countries maintaining commerce as usual. He points out that the formula used for calculating the rates of “reciprocal” tariffs bears no resemblance to any kind of economic reality, and that a 10 per cent rate has been applied to, for example, the Heard and McDonald Islands—which are uninhabited.

“Trump says Great Depression would never have started if tariffs continued”: a short item by Alex Gangitano in The Hill shows the underpinning of the above. To add lustre to his tariff scheme, President Trump—whose formal training in economic and political history is, I think, limited—declared that the Great Depression would not have happened if the United States had maintained tariffs. This is, by common historiographical consent, balls: the Tariff Act of 1930, the Smoot-Hawley Act, was introduced by President Hoover against the advice of many senior economists, was a concession to special interests among the support base of the Republican Party and, by provoking retaliatory tariffs by other countries, severely damaged American exports and global trade as a whole, and made the Depression deeper than it would otherwise have been. It is impossible to say whether Trump knows this or not, but he simply states as fact wild untruths and crass stupidities, and they are taken as writ by his supporters. We are operating in a strange, not post-truth, but anti-truth political environment.

“The Pinochet affair: the pursuit of a Chilean dictator”: in The Spectator, former Supreme Court judge and historian Lord Sumption reviews Philippe Sands’s most recent book, 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia. The two men were closely involved in the matter of Pinochet’s extradition case, Sands acting for Human Rights Watch and then for the government of Belgium, Sumption advising the then-Home Secretary, Jack Straw. While noting, without criticism, that the book adopts a dramatic style which reports as if verbatim conversations which may not have happened exactly as presented, Sumption judges it “generally extremely accurate”. He deals mainly with the issue of extradition and the way in which the UK government’s policy has developed more broadly since, and in the light of, the Pinochet case. It was and is an area of great legal and moral complexity, and became so burdensome on the Home Office that the Extradition Act 2003 effectively sold the pass and instituted extradition on demand. Understandable in practical terms, but a considerable abdication of responsibility in the long run.

“My two heroes could hardly have been less alike”: the writer Ben Macintyre in The Times pays tribute to two men who have died recently, the KGB officer and British double agent Colonel Oleg Gordievsky and one of the quiet heroes of the 1980 Iranian Embassy siege, PC Trevor Lock. Macintyre stresses the huge differences in background and outlook between the two men, and suspects that, although he knew them both, they would have neither liked nor understood each other. But he draws out a more general point on the nature of heroism: neither Gordievsky nor Lock “were men of action or violence”, yet they demonstrated almost unimaginable physical and moral courage. What is striking, argues Macintyre, I think convincingly, is that neither was driven by natural recklessness or failure of imagination in the face of danger. Rather, they both found themselves in situations in which they simply could do nothing other than what they did because it was the only right and morally acceptable path forward.

“There’s so much comedy on television. Does that cause comedy in the streets?” (Dick Cavett)

“Boardroom Uncovered: Rory Sutherland”: I apologise neither for recommending Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman of Ogilvy Group, yet again, nor for plugging City A.M., for which I write weekly. Rory recently appeared on the paper’s Boardroom Uncovered podcast to be interviewed by UK editor Jon Robinson and was as fascinating and thought-provoking as ever on the future of capitalism, why Britain so rarely celebrates its entrepreneurial heroes and innovators, the blight of intergenerational wealth equality and what he would do if he was Prime Minister for a day. Lots to make you think about basic preconceptions.

“Address to the Nation on Free and Fair Trade”: after the madness of “Liberation Day” this week and some of the most fictitious economic calculations in recent history, a useful corrective from the Great Communicator. On 25 April 1987, President Ronald Reagan, speaking from Camp David in Maryland, addressed the United States in advance of the visit of the Prime Minister of Japan, Yasuhiro Nakasone. He had recently imposed tariffs on Japan as part of a dispute over semiconductors, but explained plainly and clearly why it was against his instincts to do so, why tariffs were a bad long-term policy and the corrosive effects they had. Transcript is here, if any of his successors is minded to read it…

“The Secret State: Preparing for the Worst 1945-2010”: in a 2013 speech at the Mile End Group, the great Professor Peter Hennessy talks about how the British state made plans for a potential nuclear strike by the Soviet Union and how government would be maintained. A grim subject which involved horrifyingly surreal and grim calculations, but Peter is as engaging as ever and reveals some of the hidden gems of his research which informed his book The Secret State.

“Design Classics: The London Underground Map”: this BBC documentary charts the creation of the Tube map, the product of a revolutionary thought by Harry Beck, a technical draughtsman at the London Underground Signals Office who had recently been laid off. Beck’s game-changing realisation was that a map of the Tube network didn’t need to be geographically accurate in relation to the surface or show the real distances between stations. It simply needed to show how the stations fitted together as a system, based on his experience of drawing electrical schematics. Once that intellectual leap was made, the possibilities for simplifying the map were huge and an icon was born.

Goodbyes are only for those who love with their eyes…

… as the great Persian poet and Sufi mystic Rumi once said. Because for those who love with heart and soul there is no such thing as separation.

Nice to think so. Till next time.