Sunday round-up 30 March 2025

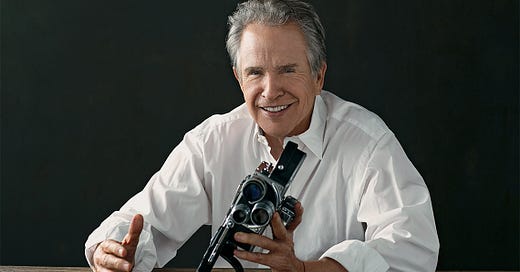

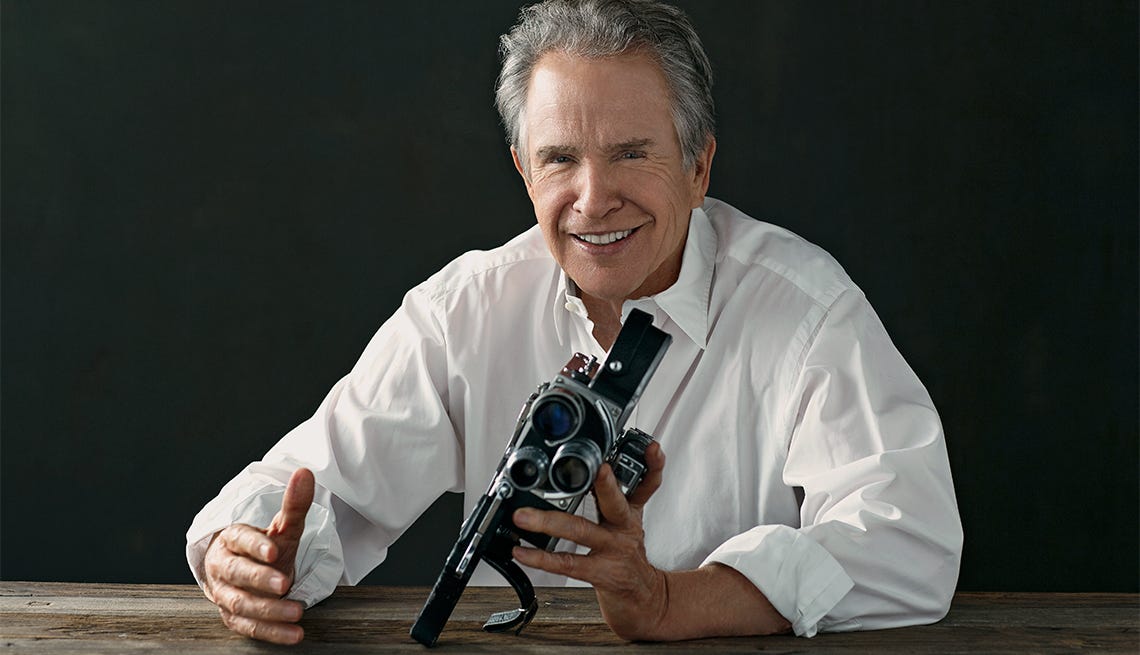

Warren Beatty is 88 and I'm not sure how I feel about that but if Clapton is in his 80s then all bets are off, as we mark the feast of top desert dude St John Climacus

Lighting candles today are Addams Family star John Astin (95), actor, director, producer, screenwriter and legendary swordsman Warren Beatty (88), World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab (87), guitar icon Eric Clapton (80), former Black Panther and anarchist Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin (78), ex-Governor of the Bank of England Lord King of Lothbury (77), Hollywood stalwart Paul Reiser (69), crime writer Martina Cole (66), actor and not-much-liked-by-Bill-Hicks rapper MC Hammer (63), former President of Mongolia Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj (62), singer-songwriter and guitarist Tracy Chapman (61), journalist, editor, talk show host and self-admirer Piers Morgan (60), singer-songwriter and (to quote Q Magazine) “beak-nosed karaoke witch” Celine Dion (57), pianist, singer-songwriter and Ravi Shankar offspring Norah Jones (46) and racing driver Colton Herta (25).

Those who once celebrated before they went from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown (or not, as the case may be) include Ottoman sultan Mehmed II (1432), painter and sculptor Francisco Goya (1746), chemist and inventor Robert Bunsen (1811), Black Beauty author Anna Sewell (1820), not-entirely-at-peace-with-himself painter Vincent van Gogh (1853), playwright and memoirist Seán O’Casey (1880), pioneering aviator and Hermann Göring’s right-hand man Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch (1892), aircraft designer Sergey Ilyushin (1894), socialite, author and philanthropist Brooke Astor (1902), prolific hangman Albert Pierrepoint (1905), former Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms (1913), singer-songwriter Frankie Laine (1913), blues musician “Sonny Boy” Williamson (1914), former United States National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy (1919), IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad (1926), novelist Tom Sharpe (1928), singer, cartoonist and sex offender Rolf Harris (1930), recently deceased Formula 1 team owner Eddie Jordan (1948), versatile actor and comedian Robbie Coltrane (1950), singer-songwriter and guitarist Randy VanWarmer (1955) and poet and novelist Tobias Hill (1970).

He liked it so much he bought the territory

On this day in 1867, the United States Secretary of State, William H. Seward, and the Ambassador of the Russian Empire to the US, Eduard de Stoeckl, signed a treaty between their respective countries under the provisions of which the United States purchased Russian America—which became the Department of Alaska—for $7.2 million (the equivalent of about $129 million today). It was renamed the District of Alaska in 1884 and the Territory of Alaska in 1912 before becoming the 49th State of the Union on 3 January 1959.

It had been the most restlessly energetic of Russian rulers, Tsar Peter the Great, who had begun the exploration of eastern Siberia and the north-western coast of North America. Vitus Bering’s First Kamchatkta Expedition (1725-31) had established the existence of a passage of water between Asia and North America, now known as the Bering Strait, and vastly expanded the detailed knowledge of the eastern regions of Siberia. While the initial impetus had come from Peter the Great, his two female successors, Anna and Elizabeth, had maintained the momentum. The more extensive Second Kamchatka Expedition (1733-43), known as the Great Northern Expedition, had seen Bering make the first Russian exploration of Alaska and find sea otters in abundance with pelts which made the highest quality fur available.

The fur trade saw promyshlenniki, Russian and indigenous Siberian merchants and traders, move into Alaska and enserf local Aleuts to hunt sea otters; during the 18th century, however, infectious diseases brought by the colonists wiped out four-fifths of the Aleut population who had no immunity to the various afflictions. Tsar Paul I sponsored the creation of the Russian-American Company in 1799, Russia’s first joint-stock company, formed from the amalgamation of a number of private enterprises including the Shelikhov-Golikov Company and its short-lived successor, the United American Company. Russia began to expand colonial settlements into North America as well as pursue fur-trading, with settlements as far as Hawaii and California, and the Russo-American Treaty of 1824 and the Treaty of St Petersburg agreed between Russia and the United Kingdom in 1825 established clearer boundaries for Russian America.

By the 1820s, the fur trade was already declining because of dwindling numbers of sea otters and other animals. The Russian-American Company had been taken under imperial control in 1818 but was poorly managed and beginning to lose substantial amounts of money. Russian settlements remained restricted to the coast of Alaska, the vast distances between the new colonies and the centre of Russian government in St Petersburg made logistics costly and vulnerable, and commercial competition with British and American interests was too much to overcome. After Russia’s defeat by the United Kingdom, France, Turkey and Sardinia in the Crimean War (1853-56), Russian America began to seem like an expensive strategic vulnerability which would be very difficult to defend in the event of further conflict. Tsar Alexander II, encouraged by his younger brother Grand Duke Konstantin, therefore made overtures to the United States about its possible purchase of the territory to forestall the possibility of its seizure by Britain.

Russia and the United States held a series of negotiations throughout the late 1850s on the possible transfer of Alaskan sovereignty, but the growing political crisis in America which led to the Civil War of 1861-65 delayed progress towards a definitive agreement. In early 1867, however, negotiations were renewed between Stoeckl, the Russian ambassador, and William Seward. The Secretary of State had been a vocal opponent of slavery, and the possibility of its spreading throughout North America had tempered his natural expansionist instincts in the first half of the 1860s, but with the victory of the Union in the Civil War and the dismantling of slavery, he began to expand his horizons. He mooted the purchase of the Danish West Indies (now the United States Virgin Islands) to provide America with a presence in the Caribbean and contemplated similar acquisitions of Greenland and Iceland as part of a programme eventually to annex Canada.

The purchase of Alaska also suited American domestic political interests. After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, President Andrew Johnson was beginning the slow and arduous task of Reconstruction in the South, while Seward had many opponents in the Republican Party and realised that an eye-catching diplomatic achievement would be a welcome distraction. Renewed negotiations culminated in an all-night session on 29/30 March 1867, until a treaty was agreed at 4.00 am. It expanded the territory of the United States by nearly 600,000 square miles, at the cost of two cents an acre, and was generally welcomed by the public as a logical step in the ongoing expansion and consolidation of American power.

The treaty was ratified by the United States Senate on 15 May, and American sovereignty became effective on 18 October. Opponents who argued that the government had acquired huge expanses of empty and worthless land dubbed the purchase “Seward’s Folly” or “Seward’s Icebox”; the population of Alaska was around 60,000, of whom the few thousand who were legally entitled to do so mostly left to go back to Russia. The beginning of the Klondike Gold Rush in 1896 transformed the economic prospects of the new territory and seemed to vindicate Seward and his supporters. Some economists have argued that the Alaska Purchase has still not provided a positive financial return for the US government, while others contend that narrow financial factors fail to take into account the broader geostrategic context of American expansion. At least crude commercial purchase of territory from other jurisdictions is unthinkable now, right?

Some devils got him

Today in 1979, Westminster was beginning to face the prospect of a general election. Two days before, the Labour government of Jim Callaghan had been defeated on a motion of no confidence by a single vote (311-310), and the Prime Minister had told the House of Commons that he would request a dissolution of Parliament and there would be a general election (it would be held on 3 May 1979). The Conservatives, led by Margaret Thatcher, were ahead in the polls by March, their lead varying from seven to 20 per cent, and privately Callaghan was pessmistic and anticipated defeat. But the result was not the foregone conclusion we sometimes allow ourselves to imagine it: the previous autumn, when there was speculation that Callaghan might call an early election, Labour and the Conservatives were much more evenly matched. A Labour victory in late 1978 was not impossible. But the Prime Minister flunked it.

Airey Neave was an unusual man. Sixty-three years old, he had been Conservative MP for Abingdon in Berkshire since 1953. In 1975, when Margaret Thatcher had stepped forward to challenge Edward Heath for the leadership of the Conservative Party after several potential rivals had fallen by the wayside, Neave, despite not knowing Thatcher very well, had volunteered to manage her campaign, and had done it brilliantly. His reward, when she became Leader of the Opposition in February 1975, was to become head of her private office and, at his request, Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary, a role which is rarely sought after.

But Neave’s background was rare too. Scion of a merchant family of baronets from Essex, he had been educated at Eton before going to Merton College, Oxford, to read jurisprudence. By his own free admission, he had done the bare minimum of work required and graduated with a third-class degree in 1938. Already commissioned as a territorial officer in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, after he graduated and with the storm-clouds of war darkening, he transferred to the Royal Engineers and was mobilised as soon as war broke out in September 1939. Sent to France five months later with 1st Searchlight Regiment, Royal Artillery, he was engaged in the Battle of France but wounded and captured by the Germans during the siege of Calais on 23 May 1940. He became a prisoner of war first at Oflag IX-A in Spangenberg Castle, then at Stalag XX-A in western Poland.

Neave escaped from Stalag XX-A in April 1941 but was recaptured by the Gestapo and sent to Oflag IV-C, more famous due to its location as Colditz Castle. After an initia unsuccessful escape attempt, he was more successful in January 1942, becoming the first British officer to make his way out of Colditz and arriving back in England via Switzerland, France, Spain and Gibraltar in April. He was awarded the Military Cross and promoted to captain, spending the rest of the war as an intelligence officer in MI9, a secret War Office section which helped prisoners of war escape from German captivity and assisted those, especially aircrew, behind enemy lines evade capture. By 1945, he had been promoted to major and awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

This extraordinary career did not fizzle out with the coming of peace. Given his intelligence background and his fluency in German—and, probably some distance behind, his unimpressive and half-hearted legal qualification—Neave was employed by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in 1945-46, focusing on the charges against arms manufacturer Gustav Krupp and his family; he also read the formal indictments to the senior Nazis who were on trial. He would eventually rise to lieutenant-colonel. But a change of career to politics was a harder slog: he was the Conservative candidate in Thurrock at the 1950 general election then Ealing North the following year, losing the latter by only 100 votes. In 1953, the MP for Abingdon, Sir Ralph Glyn, was given a peerage after representing the constituency for nearly 30 years, and Neave won the ensuing by-election comfortably.

Progress up the ladder was slow. Neave was an indifferent speaker in the House though respected by his colleagues on both sides, while ideologically he was surprisingly progressive. He had ambition, certainly, but was also driven by a strong and unaffected sense of duty, and eventually when Harold Macmillan succeeded Sir Anthony Eden as Prime Minister in January 1957, Neave was appointed Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation. Two years later he became Under-Secretary of State for Air but after a few months he suffered serious heart attack and had to give up his ministerial role. It forced him to slow his pace of life and he gave up drinking, and, although only in his early 40s, he seemed to have run put of opportunities.

That was until 1975. Despite having led the Conservative Party to defeat in three of the preceding four general elections, Edward Heath resolutely refused to consider resignation, or even that he might be at fault. Eventually and with minimal grace, he agreed to submit himself to the parliamentary party in early 1975: Heath loyalists like Willie Whitelaw and Jim Prior refused to enter the contest against their chief; Chairman of the 1922 Edward du Cann was felt to have too shady a reputation in the world of finance; and Sir Keith Joseph, clever but chronically indecisive and fatally honest, ruled himself out by a poorly worded speech which seemed to endorse eugenics.

It is often said that Neave had a deep-seated animus towards Edward Heath dating back to the 1950s; the story goes that Heath, learning of Neave’s heart attack, brusquely told him his career was finished and inspired an enduring hatred. But there is no evidence for it, and Neave never referred to the story. What did frustrate and annoy Neave, however, was that Heath was now associated with failed policies and a failed government, and seemed utterly without contrition. Someone had to challenge him, and perhaps supplant him. Neave was impressed by Thatcher, who reminded him of fearless female agents he had known during the war, and he saw in her and in no-one else a determination and sense of mission to restore Britain’s fortunes.

On 30 March 1979, Neave knew that the Conservatives were more likely than not to win the election, and that he would become Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. He was known to favour a tough, security-focused approach to terrorism and had little belief in the possibility of a political settlement; asked whether he would talk to the IRA if he was in office, he responded, “Yes, I’d say ‘Come out with your hands up’”.

His Vauxhall Cavalier had been parked in the underground car park beneath New Palace Yard in the Houses of Parliament. Neave drove up to ramp to make for the exit, and at 2.59 pm a 16-ounce bomb fitted with a mercury tilt detonator, which had been placed under his seat by members of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) earlier that day, exploded. The Commons was debating the Credit Unions Bill, and the sound of the detonation can be heard on the broadcast. The force of the bomb blast knocked Neave unconscious in the driver’s seat, severed his legs below the knee and left his face severely burned.

He was trapped in the twisted wreckage of the car, but the paramedics who arrived to try to free him so that he could be treated were unaware of his identity until 3.30 pm: an ambulance man was able to retrieve Neave’s wallet and showed it to Thatcher’s Parliamentary Private Secretary, John Stanley. The House of Commons was suspended, initially for 15 minutes, at 3.30 pm while the government hurriedly prepared a statement, but the news that the horribly injured man was Neave raced through the building. At 3.50 pm the House resumed and the Government Chief Whip, Michael Cocks, made a brief statement but gave neither Neave’s identity nor details of his condition.

Neave was freed just after 3.30 pm and rushed by ambulance to Westminster Hospital in St John’s Gardens, still unconscious. Less than 10 minutes later he was pronounced dead. Initially both the Provisional IRA and the INLA, the armed wing of a Marxist splinter group called the Irish Republican Socialist Party, claimed responsibility; the PIRA said in a statement to a Dublin newspaper, “We have this message for the British Government. Before you decide to have a general election you’d better state that you have decided not to stay on in Ireland.” The INLA had to give details of the bomb their operatives had used in order to have their statement taken seriously.

It was the second time in the 20th century that a sitting MP had been assassinated. The first, with a degree of resonance, had been Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, from an Anglo-Irish family in County Antrim though born in Longford, who had resigned as Chief of the Imperial General Staff so that in February 1922 he could be elected as the Unionist MP for North Down. He was shot to death on the step of his house in Eaton Place on 22 June 1922 by two members of the Irish Republican Army.

Margaret Thatcher was deeply affected by Neave’s murder. They had had a peculiar relationship: he was by no means a committed Thatcherite in ideological terms, though he regarded her as “really beautiful and brilliant” and had deep admiration for her strength of character; at the same time, she regarded him with some reverence for his heroic war service and thought him brave and honourable, but she also came to realise he could be surprisingly hesitant and self-doubting in private, and she sometimes found him long-winded. Thatcher learned of his death while at a media event, and it is evident how shattering a blow it was for her. Somehow, though, the enormity of the event reflected her inner steel.

Some devils got him. They must never, never, never be allowed to triumph. They must never prevail. Those of us who believe in the things that Airey fought for must see that our views are the ones which continue to live on in this country.

Ora pro nobis

Today is a moderately active day in the calendar of saints. It is the feast of St Mamertinus of Auxerre (d AD 462), a monk who became abbot of the monastery of SS Cosmas and Damian in Auxerre; of St John Climacus (AD 579-AD 649), a Syrian monk who became abbot of the monastery on Mount Sinai built on the site of the Burning Bush, which is now St Catherine’s Monastery, the oldest continuously occupied Christian religious house in the world; of St Tola of Clonard (7th/8th century AD), a hermit and monk who became Bishop of Clonard; and of SS Thomas Son Chasuhn (1838–66) and Marie-Nicolas-Antoine Daveluy (1818-66), two of the 103 Korean Martyrs put to death while on mission to the Far East.

In the United States and Australia, today is National Doctors’ Day, recognising the service of physicians, while in Spain they are marking the School Day of Non-violence and Peace, which rather speaks for itself.

Factoids

As any fule kno, the Parthenon, once the great temple dedicated to Athene, was partially in ruins when the Earl of Elgin decided in 1800 that the sculptures on its frieze, metopes and elsewhere would look nicer in Britain and began removing them. Most of the damage to the building had been done in 1687 when it was being used as a magazine by Ottoman forces and the gunpowder stored inside was ignited by a round from a Venetian mortar. However, between classical antiquity and the devastating kaboom, the Parthenon had a varied existence. It survived as a pagan temple until the last years of the 5th century AD and was converted into a church dedicated to the Parthenos Maria, or the Virgin Mary, and became the fourth most important pilgrimage site in the Eastern Roman Empire after Constantinople, Ephesus and Thessaloniki. Mediaeval Greek accounts refer to it as the Temple of Theotokos Atheniotissa. When the Byzantine Empire was occupied by Western rulers after the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Parthenon became a Roman Catholic church, though still dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In 1458, the Ottomans captured Athens, and it may briefly have been restored to the Greek Orthodox community, but by the end of the 15th century the Parthenon had been converted again, this time into a mosque. The apse was repurposed as a mihrab, a tower constructed during its Latin occupation was extended to form a minaret, the altar and iconostasis were removed and the walls whitewashed. Nevertheless, from its construction in 447-438 BC until the explosion of 1687, the basic structure of the building remained intact.

I mentioned this fact in a blog earlier this week, but it is, I think, striking enough to bear repeating. There are two Regius Professors of History in the UK, at Oxford and Cambridge, and both the current incumbents, Lyndal Roper and Sir Christopher Clark respectively, are Australians. Both spent their undergraduate years in Australia (University of Melbourne and University of Sydney) and both then spent two years of graduate study at German institutions (University of Tübingen and Freie Universität Berlin). Both completed their doctorates in England (King’s College London and Pembroke College, Cambridge) on German historical subjects (Work, marriage and sexuality: Women in Reformation Augsburg and Jewish mission in the Christian state: Protestant missions to the Jews in 18th- and 19th-century Prussia). Both have written biographies of major figures in German history (Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet and Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Life in Power). Both are Fellows of the Australian Academy of the Humanities and the British Academy. However, Professor Roper does not have a beard.

There have been 58 Prime Ministers of Great Britain and thereafter of the United Kingdom, 55 men and three women. Only 12 of them, including the current premier, were over the age of 60 when they first kissed hands with the monarch to form a government: the Earl of Wilmington (c. 69) in 1742; the Earl Grey (66) in 1830; the Earl of Aberdeen (68) in 1852; Viscount Palmerston (70) in 1855; Benjamin Disraeli (63) in 1868; Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (70) in 1905; Andrew Bonar Law (64) in 1922; Neville Chamberlain (68) in 1937; Winston Churchill (65) in 1940; Harold Macmillan (62) in 1957; James Callaghan (64) in 1976; and Sir Keir Starmer (61) in 2024.

Some people who would really like the UK to be a solidly Christian nation (those identifying as Christians dropped below half, to 46.2 per cent, for the first time at the 2021 census) try to buttress the diminishing observance of Christianity by arguing that we are still a Christian (or “Judaeo-Christian”) nation, and an occasional casus belli is the monarch’s title of “Defender of the Faith”. There are a few things to bear in mind. The title was granted to Henry VIII by Pope Leo X in 1521 to recognise the King’s authorship of a refutation of several of Martin Luther’s ideas, the Assertio Septem Sacramentorum or “Defence of the Seven Sacraments”. It was predictably revoked in 1533 by Pope Clement VII after Henry rejected papal authority, for which he was also execommunicated. Parliament confirmed the title as a matter of law by the King’s Style Act 1543.

But the English monarchs should not feel a sense of exceptionalism. In 1507, Pope Julius II granted James IV, King of Scots, the title of “Protector and Defender of the Christian Faith”, while his son James V was given the style “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Paul III in 1537 (although neither of these titles were ever formally added to the style of the monarchs). The title was retained for the sovereign in South Africa and Pakistan until 1953, in Australia until 1973 and in Canada until 2023. In 1684, Pope Innocent XI granted the title “Defensor fidei” to King John III Sobieski of Poland; 1811, King Henri I of Haiti included in his newly created style “le défenseur de la foi”; and Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia included among his many styles “Defender of the Faith”.

I have written extensively already of my antipathy towards the House of Lords (Hereditary Peers) Bill currently before Parliament, which will, if it is passed, remove the remaining maximum of 92 hereditary peers who are still entitled to sit and vote in the House of Lords. For the first time in its history, the upper house will consist solely of those appointed to their positions. The House of Lords Act 1999 excluded most of the hereditary peers, but as a concession to those who doubted that wholesale reform would ever be undertaken, the government allowed 92 hereditary peers to retain their places in the House as an interim meaure. These included hereditary peers elected by the whole peerage in proportion to the parties’ strengths in the unreformed House, and two ex officio members: the Duke of Norfolk in his hereditary role as Earl Marshal of England, and the Marquess of Cholmondeley who was in 1999 Lord Great Chamberlain (at the accession of the King he was succeeded by Lord Carrington). As the hereditary element enters its twilight, the House of Lords still contains three dukes (Montrose and Wellington, Conservatives, and Somerset, a crossbencher and former patron of UKIP) but no marquesses at all since the death of the Marquess of Lothian, the former Michael Ancram MP, last year. (I wrote about Lord Lothian just after his death.)

Although peerages are generally governed by male primogeniture, there are 89 hereditary peerages which can be held by or inherited through the female line. However, of the 150 hereditary peers who have been elected to sit in the Lords since 1999, only five have been women, and all were elected in the initial tranche: the 31st Countess of Mar, the 11th Baroness Wharton, the 16th Baroness Strange, the 18th Baroness Darcy de Knayth and the 21st Lady Saltoun. No female hereditary peer has won a by-election. The Countess of Mar retired from the House in 2020 while the other four are all deceased.

Because nothing is ever simple, there are two extant earldoms of Mar, both in the peerage of Scotland. The Countess of Mar holds the original creation of the title, the oldest peerage title in the United Kingdom: the first recognised holder is Ruadrí, who was Earl (or Mormaer) of Mar in the early 12th century, but the position is much older than that, and there was an unnamed Earl of Mar at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. The earldom was seized by King James II in 1435 and subsequently granted to a series of royal offspring who died without heirs. It was created a sixth time for James Stewart, illegitimate son of James V, along with the earldom of Moray by which he is better known, but he was stripped of the earldom of Mar by his half-sister, Mary, Queen of Scots, after rebelling against her in 1565. The following year she granted the title to John, Lord Erskine, a descendant of the ancient earls of Mar, and he therefore became both the 1st and the 18th Earl of Mar. The 6th and 23rd Earl of Mar participated in the first Jacobite Rebellion in 1715 and was attainted for treason, but his descendant, another John Erskine, had the title restored by The Earl of Mar’s Dignity Act 1824 and was recognised as 7th and 24th Earl of Mar. His grandson, the 9th and 26th Earl of Mar, died without heirs in 1866 but had in 1835 additionally established his right to the earldom of Kellie. The latter title, because it had been created under different provisions, then passed to Walter Erskine, who became 12th Earl of Kellie, while the late Earl of Mar’s nephew, John Goodeve, changed his name to Goodeve Erskine and claimed the earldom of Mar. The new Earl of Kellie made a counterclaim for the title but died before it was considered.

In 1875, the House of Lords Committee on Privileges ruled in favour of the Earl of Kellie, determining that the earldom of Mar had been a new creation in 1565 and descended only through the male line. Many questioned the decision, but the Lord Chancellor, Lord Selborne, declared it to be “final, right or wrong, and not to be questioned”. Not so fast: the Earldom of Mar Restitution Act 1885 decided that there were in fact two earldoms of Mar, and while the Earl of Kellie was confirmed in possession of the title created in 1565, the ancient earldom was separate and distinct. This older creation was awarded to John Goodeve Erskine, who became 27th Earl of Mar and was the ancestor of the current (31st) Countess of Mar. Meanwhile, the 16th Earl of Kellie is also 14th Earl of Mar; he lost his place in the House of Lords in 1999 but was awarded a life peerage the following year as Lord Erskine of Alloa Tower and eventually retired from the House in 2017.

Just to make it even simpler, the Countess of Mar is Clan Chief of Clan Mar. The Earl of Mar and Kellie is Clan Chief of Clan Erskine. Their precedence in the peerage of Scotland is determined by the Decreet of Ranking of 1606, the Countess of Mar ranking fourth and the Earl of Mar and Kellie 10th. As a consolation, the Earl of Mar and Kellie is also Premier Viscount of the peerage of Scotland by virtue of a subsidiary title, 16th Viscount Fentoun. Something for everyone.

“Reading maketh a full man; conference a ready man; and writing an exact man.” (Sir Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban)

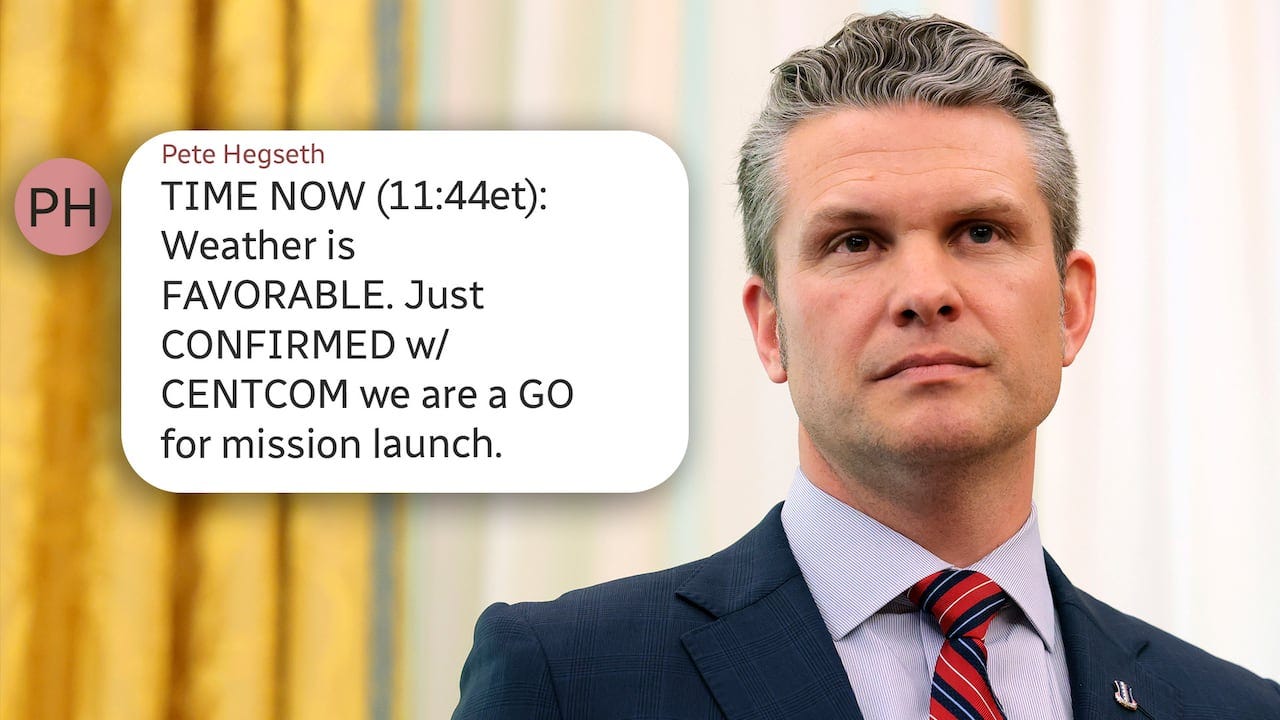

“The Trump Administration Accidentally Texted Me Its War Plans”: the security breach which saw Jeffrey Goldberg, Editor-in-Chief of The Atlantic, accidentally included in a group on encrypted messaging platform Signal is so bizarre and improbable that it can be hard to keep in mind how serious a matter it is. By accident or carelessness, it is a catastrophic failure of security protocols and a prima facie breach of the Espionage Act of 1917. The sourly inevitable and frantic attempts by various senior members of the administration to deny any fault or responsibility and instead to retaliate at Goldberg simply deepened the surreality of the whole affair. Let’s be absolutely clear: if this had been the action of an official rather than a senior political figure, his or her continued employment would have been measured in minutes and he or she would have been escorted to the nearest exit of the building. If a British minister had done what it seems National Security Advisor Michael Walsh did, it would be an immediate and unquestioned resignation matter. But we do not live in normal times and the Trump administration includes deeply unserious people committed above all to self-preservation. Amid all the brouhaha, however, it is worth taking a few minutes to read Goldberg’s meticulous, damning and surprisingly funny account of what happened.

“Elon Musk is wrong about GDP”: a satisfying essay by Tim Harford in The Financial Times takes issue with Elon Musk’s absurd contention that measurements of GDP should exclude government spending because “otherwise, you can scale GDP artificially high by spending money on things that don’t make people’s lives better”. Calmly and methodically, Harford sets out what gross domestic product is supposed to measure and what its limitations are—and as a general economic metric they are considerable—but argues that Musk is making a basic category error in trying to modify the definition of GDP to measure something he wants to demonstrate. It is, Harford says, “like trying to get a measure of your life expectancy by starting with the market value of your car and making a few adjustments from there”.

“A quick history lesson for the US from the European freeloaders”: a thoughtful and elegant article from The Times by Hugo Rifkind points out that the visceral anti-European sentiment of many senior members of the Trump administration is a manifestation of deep-seated ignorance and, more importantly, represents in many ways an inability to understand how international relations work in anything beyond a very superficial sense. There is absolutely no guarantee that the new boorish swagger of American foreign policy will be to America’s advantage overall and may undermine what were previously beneficial relationships for the sake of performative posturing: “America seems like a pushy spouse, demanding that Europe share chores equally, while simultaneously being unwilling to sacrifice the control freakery of dictating exactly what those chores have to be”.

“The disorder of succession”: after what seemed like increasingly ominous signs from the Gemelli University Hospital, Pope Francis’s health seems to have stabilised somewhat—he is 88 years old, after all—almost as if a range of crises elsewhere in the world persuaded the pontiff to delay his departure from this life until a quieter period. But the end of his pontificate is clearly approaching. In The Critic, Jaspreet Singh Boparai looks at the various scandals and controversies plaguing the Catholic Church as it is forced to contemplate at some point soon a succession and the factors which will play out in a conclave to select the next occupant of the Throne of St Peter. Reformists inside the church and their sympathisers outside (as anyone who saw the curate’s egg which was the recent film Conclave will have become aware) seem to have identified support foe the Latin Mass as a symbol of reaction and conservatism which must be opposed. The church finds itself divided within, at least in the West, with congregations falling and behavioural and doctrinal adherence almost notional. The choice of the College of Cardinals when the time comes could have very far-reaching consequences.

“Labour’s popularity contest”: in The Spectator, political editor Katy Balls (soon to move to The Times and The Sunday Times as Washington editor) looks at the popularity of leading cabinet ministers with the membership of the Labour Party, and finds a dynamic which has long been more familiar among Conservatives: there is a substantial variance between party members and the wider electorate. Within Labour, the most popular figures are Ed Miliband, Angela Rayner and Lisa Nandy, while Wes Streeting, often touted as a future leader, is mid-table at best and the Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, is in freefall. At this stage it is a wholly theoretical exercise, since, no matter how grim things may seem, Sir Keir Starmer faces no plausible challenge to his leadership. But there is a wider point which all parties should reflect on, that it is almost inevitable that active and committed party members will look at the world very differently from the average voter. Bridging this divide, as any successful party must, is becoming more and more difficult.

“The only excuse for not having a TV in your home is, you’re too fat to fit into Best Buy to get one.” (Jimmy Kimmel)

“Civilisation under threat”: on 19 October 1982, former Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, then aged 88, gave the first Carlton Lecture at the Conservative Party’s social home, the Carlton Club. It was nearly 20 years since his abrupt resignation, and he had seemed an old man then, but he enjoyed an astonishing Indian summer as a wry but sometimes sharp critic of Thatcherism, though Margaret Thatcher held him in enormous regard and ennobled him as 1st Earl of Stockton in 1984. Here he gives an impressive performance, a tour d’horizon of the fate of civilisations (without notes, but by then his eyesight was so bad he could barely read). My own view is that much of the substance is misguided or wrong, but the delivery is either delightful or revolting according to taste. Supermac was learned, erudite, witty and seemingly languorous (though in reality profoundly anxious, tightly wound and depressive), but he seemed to his audience what he was, a figure from another age, a great Whig patrician. It is certainly a style, pace and delivery which, even 40 years ago, was vanishingly rare: but it’s important to remember that Macmillan was a supreme actor, and had long played the role of defeated seer and fragile old man. In fact, he was not much of either, as a brutal pragmatist in politics when necessary who lived to nearly 92. He certainly had style.

“My Brain: After the Rupture”: I cannot claim to know Clemency Burton-Hill but I do have mutual friends with her which has long added a slight sharpness of reality for me to her dreadful experience suffering a brain haemorrhage caused by a cerebral arteriovenous malformation in January 2020. In this BBC documentary she is honest about the limitations which she now endures and, for all that her survival and recovery are remarkable, the devastation a brain injury wreaks on people’s lives. It should not make it more heart-rending that she was so active and creative a figure before her injury, a journalist, musician, presenter, actress and novelist, and there is no moral hierarchy of suffering, but it does sharpen the sense of brutality and loss. A reminder of how fragile, complex and barely understood a network of connections and pathways we all carry around and often take for granted.

“Wogan: The Best of”: on Saturday BBC4 showed an agreeably nostalgic compilation of interviews from the late Sir Terry Wogan’s eponymous chat show, featuring Sir Elton John, Omar Sharif, Selina Scott, Patrick Duffy, Elaine Stritch and others. Setting aside the warm glow of hazy memories, I am more and more convinced that Wogan was underrated and regarded as a lacking in substance because he was in fact supremely good at what he did, and so, like many people who are very good, made it look effortless. Although the apparent appetite for long-form podcasts gives some grounds for optimism, I was prompted by a recent article from Alec Marsh in The Spectator (which coincided with something I’d previously written about Sir Michael Parkinson in The Critic) to reflect on the paucity of gimmick-free, wide-ranging and perceptive interviews available now. Have times simply changed, or is there a gap in the market? To quote Fry and Laurie, where are the Ned Sherrins of tomorrow?

“The Big Sleep”: this week BBC4 screened Howard Hawks’s brilliant 1946 adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s thriller, with Humphrey Bogart at the top of his game as sardonic, world weary private detective Philip Marlowe and Lauren Bacall, barely into her twenties, electrifying as femme fatale Vivian Rutledge. The pair had begun a relationship during the making of To Have and Have Not (1944) and married between the production and release of The Big Sleep, and their on-screen chemistry was impossible to ignore. Bacall’s effortless ability to go toe-to-toe with Bogart in dramatic scenes is astounding, it brilliantly captures the atmosphere of Chandler’s depiction of the Los Angeles of the 1930s and 1940s: impossible glamour and wealth cheek-by-jowl with corruption and sordid, sleazy hedonism. It can be hard to remember that Chandler, creator of the acerbic, wise-cracking tough guy Philip Marlowe, was an old boy of Dulwich College, like P.G. Wodehouse, C.S. Forester, Sir Ernest Shackleton and, well, Nigel Farage.

Adieu…

… as the Prince of Morocco tells Portia. I have too grieved a heart to take a tedious leave. Thus losers part.

Well, maybe not.

Eliot, as you know I am a good centre-lefty (with the emphasis on centre) in good standing, so being this I am of course very concerned about Climate Change. However, given the Defence and security and US alliance issues it seems clear to me that all of us (Torys having to accept higher taxes, welfare campaigners having to accept cuts, international development types having to accept we need to look after our own backyard for a bit) so in the desperate search for cash to pay for what needs to be paid for I am wondering just how much money the UK would get if it approved the North Sea oil fields that are currently under review.

Firstly it seems to me ( a person who would be happy to see a solar panel on every roof in the country and a coastline plastered with windmills and tidal power) that even with those things, we are still going to be using oil for at least the next 30 years and even if we don't China, Africa, Sth America still will be, so leaving that in the ground won't mean less oil is used, it will just be used to make some of the most awful regimes on earth even richer and have export Tarriffs applied by Trump (is that the right word for taxes on exports??) or retaliatory Tarriffed as a way to hit his political base, so why not just get the money from what is the property of the British people (the bit, where on the off chance you are not a Tree Tory and are actually open to this, the bit where we will likely disagree is I would go full Sovereign Wealth Fund Norway style with it and not let BP or anyone anywhere near it and keep all the profit in the Treasury), but my question I hope you have the answer too, before I burn bridges with my climate change activist centre-left brothers is, just how much oil are we talking about in these fields, is it in the 100s of billions range over 30 years, or are we talking 10 or 20 billion where after costs its barely worth the effort and political blowback

I just feel pace McSweeney, that the Red Wall would like this, that it makes economic sense and considering we are still going to be importing the stuff during the transition it even makes environmental sense rather that polluting ships transporting the exact same product from some of the most vile regimes on earth, hell we might even be able to sell some into Europe and use that as a way to bring down some trade barriers

Crazy talk or if we truly live 'in a new world' (which I strongly believe we do) isn't this one of those 'all options on the table' things we need to be talking about

You might be amazed/amused/vaguely interested that St Tola has had an edible afterlife as a very fine and delicious goat's cheese 🧀 https://www.st-tola.ie/

Possibly you will find it in The Fromagerie in Marylebone but idk 🤷♂️ 😐