Sunday round-up 24 November 2024

Birthday wishes for Billy Connolly, "Beefy" Botham, Arundhati Roy and Stephen Merchant, the Battle of Solway Moss and Evolution Day

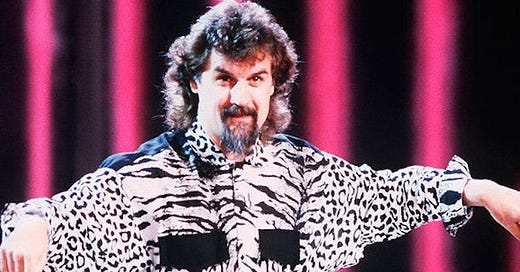

It’s a rich and varied collection of birthday boys and girls today, so parp your plastic party horns for former NATO Secretary General Willy Claes (86), one-time Beatles drummer and civil servant Pete Best (83), iconic Scottish comedian, author, writer, singer and banjo player Sir Billy Connolly (82), long-time White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater (82), Incredible String Band founding member Robin Williamson (81), A-Team hero and serial mental hospital escapee Dwight Schultz (77), Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and former Chief Medical Officer for England Dame Sally Davies (75), lawyer, Alan Sugar associate, papyrologist and taker-of-no-shit Dr Margaret Mountford (73), godfather of modern Mercedes-Benz motorsport Norbert Haug (72), legendary England cricket all-rounder Lord Botham (69), broadcaster, journalist and quietly aristocratic Roman Catholic Edward Stourton (67), Indian writer and activist Arundhati Roy (63), tenor and actor Russell Watson (58), actor, director, producer and screenwriter Stephen Merchant (50), actress and producer Katherine Heigl (46) and singer-songwriter Tom Odell (34).

Cake has gone stale for the departed previously celebrating today, including Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632), Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Laurence Sterne (1713), 12th President of the United States Zachary Taylor (1784), priest and creator of rugby football William Webb Ellis (1806), novelist and playwright Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849), painter, illustrator and absinthe enthusiast Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864), pianist and ragtime pioneer Scott Joplin (1868), military genius Field Marshal Erich von Manstein (1887), How to Win Friends and Influence People author Dale Carnegie (1888), Italian-American gangster Charles “Lucky” Luciano (1897), conservative writer, polemicist and broadcaster William F. Buckley Jr (1925), spree killer Charles Starkweather (1938) and serial killer Ted Bundy (1946).

Bad day for Scotland

On this day in 1542, a Scottish army of 15-18,000 soldiers under the command of Lord Maxwell, Warden of the West March in Scotland, crossed the border into England in response to a raid by an English force in August. At Solway Moss near the River Esk, 12 miles north of Carlisle, Maxwell encountered 3,000 English troops commanded by Sir Thomas Wharton, the English Warden of the Western March who had represented Cumberland in the House of Commons earlier that year. The Scots enjoyed overwhelming numerical superiority but were unsettled when Sir Oliver Sinclair of Pitcairnis and Whitekirk, a courtier of James V, seems to have declared himself the King’s chosen commander in place of Maxwell; an alternative explanation is that Sinclair delivered a message from the King confirming Maxwell’s authority but the interaction was misunderstood by the watching soldiers. Either way, the command structure began to disintegrate and when the armies clashed, the Scots found themselves penned between the Esk and the peat bog of Solway Moss. Hundreds of Scottish soldiers drowned and after fierce fighting the Scots army surrendered to Wharton’s much smaller force. Casualties in the battle itself were extraordinarily low, around 20 Scotsmen and seven Englishmen dying, but the English took 1,200 prisoners including several leading noblemen. James V, who had remained at Lochmaben in Dumfriesshire due to illness, was shocked by news of his army’s rout; he travelled to Linlithgow Palace to visit the Queen, Mary of Guise, who was heavily pregnant, then on 6 December moved to Falkland Palace in Fife. He had suffered recurring bouts of illness and now sickened badly, taking to his bed.

The King was probably suffering from cholera or dysentery and seems to have foreseen his imminent death: when news arrived that the Queen had given birth to a daughter, now his heir, James is reputed to have mourned of the crown, “It cam wi’ a lass, and it will gang wi’ a lass”. (The Stewarts had inherited the throne through a female claimant; his two infants sons, James, Duke of Rothesay, and Robert, Duke of Albany, had died on successive days in April 1541.) On 14 December, he died, aged 30, and was succeeded by his six-day-old daughter, Mary Queen of Scots.

The Irish Question: fire away

Today in 1922, nine members of the Irish Republican Army’s anti-Treaty faction were executed by firing squad at Beggars Bush Barracks in Dublin, the headquarters of the Provisional Government’s National Army. Among them was Erskine Childers, the 52-year-old Anglo-Irish author of The Riddle of the Sands (1903). He had devoted himself to the cause of Irish independence since 1914, helping to organise the smuggling of rifles from Germany to the Irish Volunteers that summer, although he served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, the Royal Naval Air Service and then the nascent Royal Air Force between 1914 an 1919, leaving as a major and having won the Distinguished Service Cross at Gallipoli in 1915. He volunteered to assist Sinn Féin, whose MPs elected in December 1918 had met the following month at the Mansion House in Dublin and declared themselves the first Dáil Éireann. In August 1921 he was elected unopposed to the second Dáil for Kildare-Wicklow, voting against the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January 1922 despite having been secretary to the Irish delegation which negotiated it. But he was marginalised by the anti-Treaty IRA forces in the ensuing civil war as “that bloody Englishman”.

Childers was arrested on 10 November and sentenced to death by a court martial for possession of a firearm, an offence under the Army (Emergency Powers) Resolution. An appeal to the Master of the Rolls of Ireland, Charles O’Connor, was dismissed and another lodged with the barely established Supreme Court, but it had not even been accepted before the sentence was carried out. Before his execution, Childers shook the hand of every member of the firing squad and made his 16-year-old son, Erskine Hamilton Childers, promise to do the same with every man who had signed his death sentence. His last words, to the firing squad, were “Take a step or two forward, lads, it will be easier that way.”

From a personal perspective, I should add that Childers was from 1895 to 1910 a clerk in the House of Commons, serving as Clerk of Petitions from 1903 to 1910. He resigned to join the Liberal Party and campaign for Home Rule for Ireland, and was adopted as parliamentary candidate for Plymouth Devonport. He was likely to win when a general election was called but resigned his candidacy when the Liberals appeared sympathetic to excluding some or all of Ulster from the Home Rule Bill (which eventually became the Government of Ireland Act 1914). When Robert Rhodes James, a clerk from 1955 to 1964, was selected as Conservative candidate for the Cambridge by-election in 1976, a former colleague is supposed to have said of this transition from clerk to would-be MP “Good God! Last man who did that got shot.” Rhodes James was elected and held the seat until 1992.

Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

It is also the anniversary in 1963 of the fatal shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby. Oswald had shot and killed President John F. Kennedy two days before (or had he?), but had been arrested within two hours of the assassination by officers of Dallas Police Department (“I’m just a patsy!” he told reporters). He was interrogated for two days at police headquarters then on Sunday 24 November was due to be transferred to the county jail, ironically located in the upper six floors of the Dallas County Criminal Courts Building on Dealey Plaza, less than two hundred yards from what was then the Texas School Book Depository: it was from the sixth floor of the latter building that Oswald had fired at the presidential motorcade.

Shortly after 11.00 am, Oswald was escorted through the basement of the police headquarters towards an armoured car, but as he left the building, Ruby emerged from the crowd of onlookers and at 11.21 am shot Oswald in the stomach at close range with a .38 calibre Colt Cobra revolver. Detective Billy Combest of the Vice Section recognised Ruby and shouted “Jack, you son of a bitch!”, although by contrast the crowd outside the building applauded when they heard that Oswald had been shot. He was taken to Parkland Memorial Hospital—where Kennedy had been taken two days before—but died at 1.07 pm of a haemorrhage after the bullet had damaged his spleen, stomach, aorta, vena cava, kidney, liver, diaphragm and 11th rib. A network television pool camera had been covering Oswald’s transfer, meaning that NBC viewers saw his murder live, with other networks broadcasting the footage within minutes.

Ruby was quickly arrested. He claimed to have been distraught at Kennedy’s death and shot Oswald to “redeem” the city of Dallas, as well as “saving Mrs Kennedy the discomfiture of coming back to trial”. It had not, he said, been premeditated but a spur of the moment action when he saw Oswald at such close quarters. Ruby also admitted he had been taking Preludin, a branded form of phenmetrazine, a central nervous system stimulant preferred by some over amphetamines and methamphetamines (the Beatles were frequent users in their early career). He later told his brother Earl he had not wanted Oswald to die. Nevertheless, on 14 March 1964, he was convicted of murder with malice in Criminal District Court No. 3 (located in the same building as the county jail to which Oswald was supposed to be transferred!) and Judge Joe Brown sentenced him to death. Ruby lodged an appeal with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals; his lawyer argued the trial should have been held away from Dallas County and that his confession had been improperly entered as evidence. The court overturned the conviction on 5 October 1966 and a new trial was scheduled for February 1967 in Wichita Falls, Texas. In December, however, Ruby was admitted to Parkland Memorial Hospital with pneumonia, and was found to have cancer of the brain, lungs and liver. He died of a pulmonary embolism on 3 January 1967. Before his death, he had been questioned by the Warren Commission, established to investigate President Kennedy’s assassination, but its report found nothing to connect him to any kind of conspiracy or that he and Oswald had been acquainted.

Party time, excellent

Festally, today we remember St Chrysogonus, a 4th century AD martyr killed in Aquileia during the Diocletianic Persecution; St Colmán of Cloyne (AD 530-AD 606), a Munster-born monk and one of the earliest poets to write in vernacular Old Irish; St Eanflæd (AD 626-AD 685), a Deiran princess and daughter of King Edwin of Northumbria and St Æthelburh of Kent, who married King Oswiu of Northumbria (his brother Oswald had succeeded her father Edwin, who in turn had sent an army to defeat and kill their father Æthelfrith, then succeeding him as king) then became Abbess of Whitby as a widow; SS Flora and Maria, two of the nine Martyrs of Córdoba who were beheaded under Shari’a law in AD 851 for apostasy (Flora) and blasphemy (Maria), their corpses left in the open for a day then thrown in the River Guadalquivir; St Albert of Louvain (1166-92) who became Bishop of Liège in a contested election and was murdered outside Reims by three German knight supporting his enemy Count Baldwin V of Hainaut; and of St Andrew Dung-Lac and Companions, known collectively as the Vietnamese Martyrs, canonised in 1988 as representatives of the 130-300,000 Vietnamese and missionaries who were killed for their faith in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Today is Evolution Day, marking the date in 1859 on which Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life was published. It emerged in the mid-1990s and is related to the better-known Darwin Day (12 February) which marks the author’s birth in 1809. Meanwhile India recognises Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Martyrdom Day (Shaheedi Divas), remembering the ninth of 10 gurus who established Sikhism between 1469 and 1708 and was executed in Delhi on the orders of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1675.

Factoids

Surely the best line in John Woo’s 1996 Broken Arrow is when White House Press Secretary Giles Prentice (Frank Whaley) says of the titular phrase, “I don’t know what’s scarier, losing nuclear weapons, or that it happens so often there’s actually a term for it”. It is quite accurate: “Broken Arrow” is the term used by the United States military to describe an unexpected event involving the accidental launching, firing, detonating, theft or loss of a nuclear weapon. It is calculated that there have been 32 such incidents since 1950, which sounds like an alarmingly high number, but what may give you even more concern is that six devices lost by the United States remain unaccounted for. The first was lost on 13/14 February 1950: a US Air Force Convair B-36 Peacemaker of the 7th Bombardment Wing, Heavy, was carrying out a simulated combat mission, flying from Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska to Carswell AFB in Texas, when it developed serious mechanical problems and the crew was forced to shut down three of the aircraft’s six piston engines (it also had four jet engines). Rather than risk crashing with a nuclear weapon on board, the captain was ordered to jettison the Mark 4 atomic bomb over the Pacific Ocean. The weapon contained 5,000 lbs of explosives and a substantial amount of natural uranium but no plutonium core, essential for nuclear detonation. Dropped from 8,000 feet, the bomb exploded on impact with the surface of the Inside Passage off the coast of British Columbia, causing a bright flash and a shock wave, caused by the conventional explosive. The aircraft then flew over Princess Royal Island where the crew of 17 bailed out. Twelve were found alive, but whatever remains of the Mark 4 bomb has never been recovered.

The most recent unrecovered loss occurred in May 1968. The USS Scorpion, a Skipjack-class nuclear-powered attack submarine, was en route from the Azores, where she had been monitoring Soviet naval activity, to her home port of Norfolk, Virginia. The last radio message from the captain, Commander Francis Slattery, had received on 21 May by a US Navy radio station at Nea Makri in Greece, saying that USS Scorpion was closing on the Soviet submarine and research group, running at a steady 15 knots and a depth of 350 ft “to begin surveillance of the Soviets”. The submarine was expected to arrive in Norfolk around 1.00 pm on 27 May but never appeared. She was declared “presumed lost” on 5 June, and struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 30 June. The wreckage was found 400 nautical miles south-west of the Azores in October 1968 at a depth of nearly 10,000 feet, and its two Mark 45 ASTOR nuclear-armed torpedoes are presumed still to be in the torpedo room, which largely survived the submarine’s implosion.

I mentioned above that former clerks of the House of Commons Erskine Childers (1895-1910) and Robert Rhodes James (1955-64) became parliamentary candidates and, in the latter’s case, a Member of Parliament. As far as I am aware, the only other clerk to cross that very wide Rubicon was the Irish Nationalist John Redmond, MP for New Ross (1881-85), North Wexford (1885-91) and Waterford City (1891-1918). From 1900 to 1918, he was leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, the group of Irish MPs who campaigned for Home Rule. In the late 1870s, he worked as assistant to his father, William Redmond, MP for Wexford, then was very briefly in 1880, a clerk in the Vote Office, which is responsible for the provision of documents and printed material to MPs and House of Commons staff. He approached the Nationalist Party leader, Charles Stewart Parnell, in the hope of succeeding his father as MP for Wexford when he died in 1880 but the candidacy had already been promised to Parnell’s secretary, Tim Healy. He was then elected unopposed for New Ross at a by-election in January 1881.

On this date 33 years ago, Queen frontman Freddie Mercury died, aged 45. You may know that he was born Farrokh Bulsara to Parsi-Indian parents in the Sultanate of Zanzibar, then a British protectorate ruled by Sultan Sir Khalifa II bin Harub Al-Busaidi. His father, Bomi Bulsara, had moved to Zanzibar from Bulsar, near Bombay, as a young man and worked in the High Court of Zanzibar, becoming Cashier. The family practised Zoroastrianism, which leads to the question: is Freddie Mercury (at least in the West) the most famous Zoroanstrian? The only challengers I would suggest would be the Persian kings Cyrus the Great, Darius the Great and Xerxes the Great; Lord Bilimoria, founder of Cobra Beer; comedian and actress Nina Wadia; and conductor Zubin Mehta, which is a diverse group. But it still has to be Freddie, I think.

Other notable but less world-renowned Zoroastrians include Sir Jamshedji Nusserwanji Tata, founder of Tata Group; Dadabhai Naoroji, Liberal MP for Finsbury Central 1892-95 and the first Asian elected to the House of Commons; closely followed by Sir Mancherjee Merwanjee Bhownaggree, Conservative MP for Bethnal Green North East 1895-1906; Feroze Gandhi, later a member of the Lok Sabha for Rae Bareli, who in 1942 married Indira Nehru, daughter of the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru (1947-64), and herself third Prime Minister 1966-77 and 1980-84; Cornelia Sorabji, the first woman to read law at the University of Oxford, sitting the examination for Bachelor of Civil Law (BCL) at Somerville Hall in 1892 by special permission of Congregation (she could not formally graduate until 1922, after the passage of the Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act 1919; Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, Indian Chief of the Army Staff and the first Indian to hold the rank of field marshal; and novelist and screenwriter Rohinton Mistry.

It’s best to avoid the phrase “The Nazis gave a bad name to…” but it is certainly true of eugenics, which, to many in the early 20th century, seemed a rational extension of science to improve the health and condition of the population. Sybil Gotto, the widowed daughter of senior Royal Navy officer, and the octogenarian pioneer of the discipline Francis Galton (half-cousin of Charles Darwin) founded the Eugenics Education Society in 1907, renamed the (British) Eugenics Society in 1924. (In 1989, it was renamed the Galton Institute in 1989 and the Adelphi Genetics Forum in 2021; yes, it’s still going.) For an idea of how respectable eugenics was before Nazism, the society’s members included: prime ministers the Earl of Balfour, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill; Dr Charles D’Arcy, Archbishop of Armagh; social reformer Henry Havelock Ellis; founding President of Stanford University Professor David Starr Jordan; legendary economist Lord Keynes (director of the society 1937-44); birth control pioneer Marie Stopes; godfather of the welfare state Lord Beveridge; colonial administrator and Conservative MP Sir Arnold Wilson; the “father of transplantation” and Nobel laureate Sir Peter Medawar; and inaugural Professor of Social Administration at the London School of Economics Richard Titmuss.

Henry VIII is the only English or British monarchy to have ruled part of modern-day Belgium. During the War of the League of Cambrai (1508-16), an English and Imperial army defeated the French at the Battle of the Spurs (16 August 1513) then laid siege to Tournai, a city on the River Scheldt nominally controlled by France but exercising considerable autonomy under its bishop. The city fell to Henry VIII on 23 September, and the King appointed the Master of the Mint and his boyhood tutor, Lord Mountjoy, as governor. In 1514 Thomas Wolsey, Lord High Almoner, Dean of York and the King’s closest adviser, was named Bishop of Tournai (he was a collector of ecclesiastical and temporal offices: that same year he became Bishop of Lincoln then Archbishop of York and in 1515 he became Lord High Chancellor and a cardinal). The city seems also to have been represented in the House of Commons: Henry VIII’s second Parliament (1512-14) was that point prorogued and the four civic councils were asked to nominate Members of Parliament, one of whom was Jean le Sellier, the senior Prévôt or provost of Tournai. He raised a number of issues relating to the city which were addressed by the Debts to Merchants of Tournai, etc. in France Act 1513. It is not known if Tournai was represented in Henry’s third parliament of February to December 1515. The Treaty of London, a non-aggression pact drafted by Wolsey and signed in October 1518 by England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Burgundy, the Habsburg Netherland and the Papal States, returned Tournai to French sovereignty in exchange for 600,000 crowns.

The only other city outside the British Isles to be represented in the House of Commons is Calais. It had been captured in 1347 by Edward III and English sovereignty was confirmed by the Treaty of Brétigny in October 1360. Henry VIII reformed its governance in the Ordinances of Calais Act 1535, which provided for two Members of Parliament to be returned to the House of Commons; one was to be chosen by the Lord Deputy and his council, the other by the Mayor and Council of Calais. MPs sat in 10 parliaments from 1536 to 1555, and a writ was issued for the election of Members in 6 December 1557. In January 1558, however, the city was besieged by a French army under the Duke of Guise, and on 7 January, realising the hopelessness of his position, the Lord Deputy, Lord Wentworth, surrendered to Guise. It was England’s last relic of the Hundred Years’ War and the shock of its loss was profound. On her deathbed in November that year, Queen Mary said to her ladies in waiting, “When I am dead and cut open, they will find Philip and Calais inscribed on my heart”.

There was a proposal in the 1950s for Malta to be represented in the House of Commons. The Crown Colony of the Island of Malta and its Dependencies had been established in 1813, and the bicameral Parliament of Malta, consisting of a Senate and a Legislative Assembly, was established in 1921, along with a Head of Ministry. However, the Constitution was suspended in 1930-32 and 1933, Malta reverting to its Crown Colony status, before self-government was restored in 1947. To address continuing dissatisfaction, in July 1955 the Prime Minister, Sir Anthony Eden, announced a Round Table Conference, chaired by the Lord Chancellor, Viscount Kilmuir. One of its tasks was “to consider constitutional and related questions arising from proposals for closer association between Malta and the United Kingdom and, in particular, from the proposal that Malta should in future be represented in the Parliament at Westminster”. The conference reported in December 1955, recommending that Malta be given three seats in the House of Commons and responsibility for the island be transferred from the Colonial Office to the Home Office. The Parliament of Malta would control everything except foreign affairs, defence and taxation. The proposals were approved by a referendum in Malta in February 1956, though the process was boycotted by the opposition Nationalist Party, leading to a turnout of only 59 per cent. The matter was debated in the House of Commons in March 1956, and fears were expressed that it might set a precedent for the representation of other colonial possessions. The government, acknowledging the controversy in Malta, did not proceed. On 21 September 1964, the State of Malta was proclaimed under the terms of the Malta Independence Act 1964. The Queen remained head of state (as Queen of Malta) and was represented by a governor-general, until the island declared itself a republic on 13 December 1974.

Malta is one of three collective recipients of the George Cross, the United Kingdom’s highest award for non-operational gallantry. It was granted by George VI on 15 April 1942 during the two-and-a-half-year siege of Malta by Germany, “to honour her brave people” and “to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history”. The GC was incorporated into the country’s flag in 1943. The other two collective awards were both made by Elizabeth II: to the Royal Ulster Constabulary in November 1999; and to the National Health Service in July 2021.

“Television is actually closer to reality than anything in books.” (Camille Paglia)

“Loaded: Lads, Mags and Mayhem”: this BBC documentary charting the birth and rise of the magazine Loaded, perhaps the archetypal “lads’ mag”, is deeply resonant for (men of) my generation. It was launched in May 1994 under the editorship of James Brown, formerly of NME and The Sunday Times Magazine, and its tagline summed up a distinctive cultural strand of the 1990s, “For men who should know better”. Its irreverent stew of celebrity interviews, gonzo journalism, sport, light-hearted vulgarity and women without many clothes was a back-hand to the pious spirit of the decade’s first few years and it offered nothing more than fun. Unlike aspirational publications like Arena and GQ, Loaded sold itself as reflecting real life in all its highs and lows. Was it part of a culture which soured into sexism and excess? Undoubtedly. Was that inevitable? Possibly. Did that section of journalism need a shock to the system? Absolutely. Fascinating and thoughtful, though Brown may annoy.

“David Patrikarakos: My Martin Amis”: a podcast from earlier in the year which I came across by accident but which proved to be a hidden gem. David Patrikarakos is an author and journalist whom I’m lucky know a little bit, and who wrote a brilliant study of the role of social media in modern conflicts, War in 140 Characters: How Social Media Is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty-First Century. He is also, it transpires, an obsessive devotee of the late Sir Martin Amis, and spoke to the host of My Martin Amis, Jack Aldane, about his obsession and in particular about Amis’s first novel, The Rachel Papers. Listening to someone talk about a subject that matters deeply to them is almost always interesting, but I found this particularly fascinating for the discussions of Amis’s prose style and his relationship with the late Christopher Hitchens.

“Say Nothing”: starting with the caveat that I’ve only watched the first episode, this Josh Zetumer nine-part series is adapted from Patrick Radden Keefe’s 2018 book, and traces the lives of people growing up in Belfast during the Troubles. It deals particularly with the abduction and murder of Jean McConville, a 38-year-old mother of 10 who was kidnapped at gunpoint from her home in the Divis Flats in west Belfast in 1972. She was shot in the back of the head and her body buried on Shelling Hill Beach in County Louth, only being found in 2003; the IRA had “executed” her for being an informer (almost certainly not true). Say Nothing has garnered controversy; one of McConville’s sons, Michael, has described it as “horrendous” and said “I have not watched it nor do I intend watching it”. The critical reception has been generally positive but it will be fascinating to see how the portrayal of Gerry Adams (played by Josh Finan as a young man then Michael Colgan when older) resonates: Adams has consistently maintained he was never a member of the Provisional IRA, a claim believed by virtually no-one and belied by his depiction in Say Nothing. (Each episode ends with the solemn disclaimer “Gerry Adams has always denied being a member of the IRA or participating in any IRA-related violence”.) Worth watching for an insight into the Troubles.

“Spectator TV: Rory Sutherland on Jaguar’s bizarre rebrand”: regular readers will know I miss few opportunities to bang the drum for Rory Sutherland, Vice-Chairman of Ogilvy Group, and this week is no exception. Jaguar’s rebranding launch has been poorly received, it’s fair to say, and I presented a critique in City A.M. on Friday. In conversation with James Heale, The Spectator’s political correspondent, Rory is typically thoughtful and reserves judgement, making some telling points, though he admits it’s not a campaign he would have designed. An excellent consideration of the individual case of Jaguar but also of brand marketing more generally, touching on some potential pitfalls and common misconceptions.

“The Future of American Conservatism”: this discussion from The Atlantic Festival in September is in a sense a period piece, in that it was recorded before the presidential election, but the issues remain as relevant as ever. Evan Smith of The Atlantic talks to the hosts of The Bulwark podcast, Tim Miller, Sarah Longwell and Bill Kristol, to examine the next stage in American conservatism. There is a conundrum in that the Democratic Party, its leadership at its most progressive and far-left for more than a generation, has suffered a serious electoral reverse, and the Republicans now control the White House and both houses of Congress as well as the Supreme Court, yet there is unease. Donald Trump is not a conventional conservative—he is not a conventional anything—and for many on the right his populism, mendacity and disregard for laws and conventions are beyond the pale. For now, he seems unstoppable, but, under the Twenty-Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, this is his final term in office. His domination of the GOP is exercised through such a striking cult of personality that it is very difficult to predict what a political landscape after Trump looks like.

“Good prose is like a windowpane.” (George Orwell)

“Donald Trump’s Most Dangerous Cabinet Pick”: a hair-raising article by Jonathan Chait in The Atlantic examining the thoughts and beliefs of Donald Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth. I’ve already argued in The Spectator that Hegseth, a former Fox News presenter with no executive or legislative experience, is utterly unqualified to run the Pentagon. Chait delves into Hegseth’s background and ideology, and discovers that he is much worse than unqualified: he is a bone-deep, self-important conspiracy theorist who exists in an alternative reality. “The deist heresies of Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, he writes, laid the groundwork to implant communist thought into the school system.” It is characteristic of the current Republican Party that his first book, In The Arena: Good Citizens, a Great Republic and How One Speech Can Reinvigorate America, “evolves around ideas that Hegseth has since renounced, after converting to Trumpism”. The willingness to disavow one’s past and swear blind fealty to Trump is a vital part of making progress in the GOP now. Chait concludes that Hegseth is “almost certainly far more dangerous” than any of Trump’s other nominees for office.

“Maps of Bounded Rationality: A perspective on intuitive judgment and choice”: keeping it light-hearted with Daniel Kahneman’s Nobel Prize lecture in December 2002 after he jointly won the economic sciences prize (the other laureate was American economist Vernon L. Smith, at that point Professor of Economics and Law at the Interdisciplinary Center for Economic Science at George Mason University in Virginia). Kahneman won the prize for his work on prospect theory, which he and cognitive and mathematical psychologist Amos Tversky had developed since 1979, arguing that individuals assess their loss and gain perspectives asymmetrically. It sought to show that human behaviour cannot be rationally modelled because it is driven by relative rather than absolute judgements. (Despite winning the Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences, Kahneman, who died in March this year, had never studied economics in his life.)

“The UK doesn’t have a technology policy”: a punchy and direct piece by Alex Chalmers in CapX argues that the efforts of successive governments to nurture Britain’s tech industry have focused on exactly the wrong things, concentrating in regulation and public subsidies rather than energy costs, procurement, infrastructure and recruitment and retention. As a result the state is the biggest single investor in venture capital funds and ‘growth-stage’ technology companies, and the United Kingdom is a very difficult environment in which to scale up research or build a category-defining technology company. When progress is made, it is usually by the efforts of outsiders and disruptors. Chalmers concluded “The good news is that this is fixable. The bad news is it will require a degree of political courage and a willingness to say ‘no’ to people.”

“Will China soon rule the waves?”: in The Spectator, Peter Frankopan, Professor of Global History at Oxford, explains the global importance of trade and navigation. He highlights the vulnerability of the world’s maritime chokepoints like the Panama Canal, the Malacca Strait and the Bab el-Mandeb, and warns that China is rapidly establishing itself as the world’s predominant sea power. The relative weakness of the Royal Navy is a worrying factor in this, and Frankopan argues that the UK’s level of defence spending must increase, “not only to keep us safe from threats—but to keep sea lanes open, data cables intact, and goods and information flowing smoothly.”

“Unwilling ears: Where next for Britain’s China policy?”: in the Council on Geostrategy’s Substack, Britain’s World, Patrick Triglavcanin analyses the current government’s approach to China and finds it “as confused as ever”. The problem is not so much the competing priorities of upholding human rights, protecting our national security and interests and maximising economic opportunities; rather, the government wants to appear virtuous and principled as well as hard-headed and canny, and seems to think it can present both faces convincingly to the world. Ultimately it “ties itself in rhetorical knots in pursuit of conflicting goals which are impeding the creation of a coherent policy—even strategy—for continuing to engage the PRC”. This is one facet of a wider challenge, that Sir Keir Starmer and David Lammy, as well as other ministers, still think they can shape reality by making the right assertions with sufficient emphasis. Until the government is honest with itself, it is unlikely to find a productive way forward.

Even so, I wish you well…

… as Calypso told the departing Odysseus. If you could see it all, before you go—all the adversity you face at sea—you would stay here, and guard this house, and be

immortal.

But then, nothing lasts forever. Until next time.