Sunday round-up 18 May 2025

Birthday greetings to Rick Wakeman, Toyah Willcox and a former Black Rod, marking the birth of Norman St John-Stevas and Somaliland's Independence Day

Some housekeeping notices: as some of you will have read elsewhere I was delighted this week to join Defence On The Brink as Contributing Editor, so will be drawing attention to our output from time to time, but do have a look if it’s your area of interest.

Second: I’ve realised I’m really not watching much television at the moment, so recommending five written pieces and five things to watch seemed increasingly artificial. What I’ve done this week is to expand the written recommendations, and add in a couple of what I would call pensées, because I’m like that. I might try a few different bits in the round-up over the coming weeks and see what works, but, let’s face it, if you’re already a reader, you’ll probably put up with what my nearest and dearest affectionately think of as “my bullshit”.

Today we raise a glass to former First Lady of France Bernadette Chirac (92), former President of the European Commission and Prime Minister of Luxembourg Jacques Santer (88), ex-soldier and Canadian cabinet minister Gordon O’Connor (86), “outspoken” actress and singer Miriam Margolyes (84), singer-songwriter, guitarist and producer Albert Hammond (81), actress Gail Strickland (80), keyboard player, songwriter and Tudor-consort-fixated prog-rock icon Rick Wakeman (76), retired soldier and former Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod David Leakey (73), country music heavyweight George Strait Sr (73), possibly pseudonymous new wave and punk singer-songwriter Wreckless Eric (71), actor and screenwriter Chow Yun-fat (70), über-prolific playwright and screenwriter John Godber (69), composer, producer and ambient behemoth Enigma founder Michael Cretu (68), singer-songwriter, actress and opinion-haver Toyah Willcox (67), former Formula One driver Heinz-Harald Frentzen (58), singer-songwriter, actress, producer and stalwart of early 1990s lipstick sales Martika (56), actress, comedian and writer Tina Fey (55), former Conservative MP and repeated unfortunate-incident-sufferer Mark Menzies (54), you-do-remember-her-really singer and producer Jem (50), Wishaw-born multiple snooker world champion John Higgins (50), Minecraft co-designer Jens Bergensten (46) and sailor and official-record-denied global circumnavigator Jessica Watson (32).

Requiring no cake in the afterlife are mathematician, astronomer and poet Omar Khayyám (1048), Florentine ruler Pier Soderini (1450), well-connected participant in three papal conclaves Guido Luca Cardinal Ferrero (1537), ambassador, minister, parliamentarian and half-brother of Lord Castlereagh the Dublin-born 3rd Marquess of Londonderry (1778), journalist and pioneering photographer Mathew Brady (1822), author of the Pledge of Allegiance Francis Bellamy (1855), last Tsar of All the Russias and hubristically inadequate autocrat St Nicholas II (1868), mathematician, philosopher and historian Bertrand (3rd Earl) Russell (1872), two-time Chancellor of Weimar Germany Hermann Müller (1876), architect and Bauhaus School founder Walter Gropius (1883), director, producer and screenwriter Frank Capra (1897), tennis champion and sports broadcaster Fred Perry (1909), singer and television host Mr Perry Como (1912), fashion designer Pierre Balmain (1914), ballerina Dame Margot Fonteyn (1919), Pope John Paul II (1920), veteran Eurosceptic MP Sir Richard Body (1927), flamboyant Conservative cabinet minister, barrister and author Lord St John of Fawsley (1929), Mad cartoonist Don Martin (1931), veteran parliamentarian, journalist and writer Lord Cormack (1939), football player, coach and manager Nobby Stiles (1942), novelist, essayist and poet W.G. Sebald (1944) and former Taoiseach of Ireland John Bruton (1947).

In Bruges

At dawn on this day in 1302, a coordinated blow was struck by the local Flemish militia in Bruges against the occupying French garrison which would ignite a full-scale revolt. Flanders in the late 13th and early 14th centuries was increasingly divided between the aristocracy and their lord, the Count of Flanders, a vassal of the King of France, on the one hand and the rich, prosperous and independently minded mercantile bourgeoisie on the other. Because Flanders enjoyed a monopoly on the English wool trade to feed its burgeoning cloth industry, merchants had become sufficiently rich and powerful to demand more autonomy for their towns and cities like Bruges, Ghent, Ypres, Lille and Douai from Margaret II, Countess of Flanders (1244-78). Inevitably this created tensions and power struggles between the merchant classes and the nobility, and in the years after Margaret abdicated in 1278 in favour of her son, Guy of Dampierre, the nobles appealed to Guy’s overlord, Philip IV of France, for assistance in their competition.

Guy had no wish to see the merchants prise more power from his hands but equally understood the potential danger of closer involvement by the French crown. Philip, on the other hand, saw an opening to extend his influence in a territory the vassalage of which had been relatively theoretical since the Treaty of Verdun in AD 843. In 1294, France went to war with England over the control of the English king’s substantial territorial possessions in mainland Europe, particularly the Duchy of Aquitaine in south-western France, and Edward I renounced his status as a vassal of the King of France in right of Aquitaine. Count Guy made an enormous gamble and threw his support behind Edward against Philip, including the betrothal of his daughter Philippa to the heir to the English throne, Edward of Caernarvon.

This was enough to provoke Philip IV into direct action. He ordered the arrest of Guy and two of his sons, cancelled the betrothal and had Philippa brought to Paris. In addition, the major cities in Flanders would be taken under the “protection” of the French crown until Guy paid an indemnity and surrendered his rights over them, after which he would then hold them at the grace of the King of France. Guy’s options had narrowed dramatically, and in January 1297, rather than submit abjectly to surrender, he renounced his allegiance to Philip, and allied himself with Edward I, Count John I of Holland, Count Henry III of Bar and Count Adolf of Nassau, who had been elected King of the Romans and heir of the Holy Roman Empire.

It took the French armies nine months to conquer most of the territory of Philip’s opponents, seizing Lille and Ghent, after which a delegation from Bruges surrendered to him and an armistice was agreed. In 1299, Edward I and Philip IV agreed the Treaty of Montreuil, which betrothed Edward of Caernarvon to the French king’s daughter Isabella while Edward married Philip’s sister Margaret. The two kings cut Guy out of the discussions and, Edward having withdrawn his forces from Flanders the previous year, the Count of Flanders was left to face Philip alone and without allies. At the end of 1299, now in his 70s, he handed control of the government to his 50-year-old son, Robert.

At the beginning of 1300, the armistice expired and France invaded Flanders again. By May, Ghent, Oudenaarde and Ypres had all surrendered, Guy and his sons Robert and William were captives of Philip IV and French armies controlled Flanders. In all of these conflicts, the merchants who controlled the towns and cities of Flanders had maintained as neutral a stance as possible, partly to minimise damage and destruction of property, and partly because they had no love for Guy and no stake in buttressing his control of the county. Their neutrality had made the conquest of Flanders much easier for the French, but the wealthy merchants, as might have been predicted, found Philip IV no more easygoing or hands-off a ruler than Guy had ever been. Meanwhile some of the rural aristocracy sought alliance with the King of France, becoming known as Leliaards after the fleurs-de-lys on his coat of arms.

Philip had appointed his kinsman Jacques de Châtillon, Lord of Leuze, Condé, Carency, Huquoy and Aubigny as Governor of Flanders with his seat at Bruges, and it was not a successful or diplomatic choice. Châtillon imposed heavy taxes on the urban elites and quickly became a hate figure. In May 1301, Philip IV decided that he and Queen Joan would undertake a tour of Flanders and make a ceremonial entry to each of the major cities. The Leliaards stages extravagant celebrations as signs of loyalty, but in places they were weak, like Ypres and Bruges, the ceremonies seemed half-hearted. They were undoubtedly expensive, and Châtillon increased his unpopularity by recouping the money through additional taxation on the merchants.

In Bruges, Pieter de Coninck, a leading member of the weavers’ guild, was imprisoned along with 25 others for suspected disloyalty to the Governor and the French crown. He was quickly freed by the local populace but then ousted from Bruges by a small force under Châtillon, only to reestablish control at the end of 1301. In May 1302, Châtillon returned with 1,500 or 2,000 knights, tore down parts of the city walls and occupied Bruges. There were rumours that leading dissidents and their families would be arrested and executed.

On the evening of 17 May, Châtillon held a feast for his soldiers. They retired for the night, and as dawn broke, a militia led by de Coninck and a butcher named Jan Breydel, each armed with a characteristic Flemish goedendag, a club with a spear-point at the end, entered the houses where the French garrison were sleeping and murdered them by the hundreds, stabbing them in the throat. It became a wider massacre of all of those suspected of connections to the French, and the Flemings had an ingenious shibboleth to distinguish ally from enemy: victims were forced to pronounce the Flemish phrase “schild en vriend” (“shield and friend”), which was very difficult for Francophones. Failing the test was fatal and punishment immediate. Estimates of the number of dead vary from 200 to as many as 2,000, and Châtillon himself only escaped by dressing as a priest after he had failed to rally his men.

The massacre, which sparked off a full-scale armed insurrection, became known as the “Bruges Matins”, named after the monastic hour at which it occurred, roughly 2.00 am or 3.00 am; it was also in emulation of the Sicilian Vespers, the uprising against French rule which had begun in Palermo at Easter 1282 and led to a war which at that time was still ongoing. Philip IV’s younger brother, Charles of Valois, had led a French army to try to reclaim Sicily that same year, 1302. The effective independence of Flanders was secured three years later under the Treaty of Athis-sur-Orge, although its terms were so financially onerous that it was unsustainable, and led to a popular uprising by the Flemish peasantry.

Every man shall be free… sort of

In 1652, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was celebrating its eighth anniversary, having been founded by Puritan minister the Revd Roger Williams, a committed advocate of religious liberty and the separation of church and state. He had been exiled from the Colony of Massachusetts Bay for questioning the right of the King to award charters of land belonging to native Americans, and acquired land from the Narragansett chiefs Canonicus and Miantonomoh which he named Providence Plantations. Williams forged deep and mutually trusting relationship with the local tribes, especially the Narragansett, and established a territory based on majority rule in “civil things” and freedom of conscience in matters of religion. Providence and the settlements of Portsmouth and Newport were granted a patent by the Parliament of England in March 1644 to come together as the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, though the patent did not receive the royal seal as England was in the grip of the Civil War and the Long Parliament had rejected King Charles I’s authority.

The initial legislative and governing body of the colony was the General Court of Election, and in May 1652 it met in Warwick with Samuel Gorton, a former clothier from Manchester, as Moderator. On this day, 18 May, it passed an order banning slavery. The statute decreed that:

no black mankind or white be forced to covenant bond or otherwise to serve any man or his assignes longer than ten years, or until they come to be twenty four years of age if they be taken in under fourteen, from the time of their coming within the liberties of this Colony; and at the end or term of ten years to set them free, as the manner is with the English servants.

This was way ahead of its time, more than two centuries before America’s civil war. Admittedly, it limited a kind of servitude, still effectively chattel slavery, to 10 years, hardly progressive in modern terms, and it applied only to black slaves, with no mention of native Americans. Nevertheless it was clear that those to whom it did apply were to be “set… free” after the 10-year period had expired. It should also be noted that it was not a statute which applied to an enormous population: a census of 1680 recorded that there were 175 enslaved people in Rhode Island, including both black people and native Americans. Nevertheless, with the exception of the 1641 Massachusetts Body of Liberties, it was the first legal instrument in the colonies to prohibit slavery.

Other instruments followed: in 1659, the General Court banned any further importation of slaves from Africa, and in 1676 the prohibition of the 1652 statute was extended to native Americans. A legal superstructure was emerging which, surely, spelled the end of slavery.

Sadly, it was not so simple as that. The 1652 statute only applied to Providence and Warwick, and there is no evidence that it was widely enforced, if indeed it was enforced at all. Rhode Island could hardly afford to abolish slavery: Newport was the biggest slave-trading port in North America, receiving around half of the slave ships from Africa, though in any case it was not covered by the statute. In 1703, the General Assembly adopted what became known as the “Negro Code”, which severely restricted the rights of black people and native Americans.

If any negroes or Indians either freemen, servants, or slaves, do walk in the street of the town of Newport, or any other town in this Colony, after nine of the clock of night, without certificate from their masters, or some English person of said family with, or some lawful excuse for the same, that it shall be lawful for any person to take them up and deliver them to a Constable.

Slavery was simply too profitable. By 1774, the slave population of Rhode Island was 6.3 per cent, twice as high as any other colony, and its economy was dependent on the “triangle trade”: rum distilled from West Indian molasses was exported to Africa in exchange for slaves, who were then traded in the West Indies in return for more molasses.

It would be 1843 before slavery was absolutely prohibited in Rhode Island, under section 4 of the state’s constitution. Nevertheless I think it is worth recognising that first step, however small, however limited and however ineffectual, that was made on this day in 1652 in Warwick, Rhode Island. Every revolution has to start somewhere.

Red-letter days

It is a varied day in the world of veneration, as we mark the feasts of St Venantius of Camerino (d AD 251 or 253), a 15-year-old who was scourged, burned with flaming torches, hanged upside-down over a fire, had his teeth knocked out and his jaw broken, thrown to the lions, and tossed over a high cliff before being decapitated during the persecutions of the Emperor Decius; of St John I (d. AD 526), Pope from AD 523-26, a Sienese churchman and diplomat who led a successful mission to Constantinople only to be treated with suspicion on his return by King Theoderic the Great of Italy; of St Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury (d AD 944), wife of King Edmund I and mother of Eadwig and Edgar whom we encountered last week, who was patroness of Shaftesbury Abbey in Dorset, a house of Benedictine nuns which, by the time of its suppression in 1539 was the second-wealthiest nunnery in England (after Syon); of St Erik, King of Sweden (d 1160), of whom little is known but who is credited with strengthening Christianity in Sweden and advancing it into Finland, and who is Sweden’s patron saint; and of St Felix of Cantalice (1515-87), the first Capuchin friar to be canonised, who begged for alms in Rome and had a reputation as a healer.

In Ukraine, it is the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Crimean Tatar Genocide and the Day of Struggle for the Rights of the Crimean Tatar People, marking the beginning of the grim three-day process in 1944 by which Lavrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD, the Soviet Union’s secret police, oversaw the deportation of the Crimean Tatar population in cattle trucks from the Crimea to the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in central Asia. Officially it was collective punishment because some Crimean Tatars had collaborated with Nazi Germany (though twice as many had served in the Red Army). At least 8,000 died during the deportation process itself, and estimates for how many died thereafter range from 34,000 to 195,000; only in the late 1980s were some of the survivors and their descendants allowed to return.

Today is Independence Day in the unrecognised Republic of Somaliland, which has popped up before. For reasons which are obscure, I wrote a piece for The Hill in February 2024, suggesting that the West should recognise Somaliland as an independent state, which brought me modest acclaim from Somalilanders and visceral hostility from Somalis who abhor the idea. Somaliland claims legal succession from British Somaliland (the Somaliland Protectorate), which was administered by the Government of India from 1884 to 1898 and then by the Foreign Office (1898-1905) and the Colonial Office (1905-60), and Somalilanders seem generally positive towards the United Kingdom, which is always nice; they’ve also run a reasonably orderly, reasonably democratic state since 1991, while the Federal Republic of Somalia is more or less a failed state and a haven for terrorism. I just don’t see why we’re all in for the territorial integrity of the latter over the legitimate aspirations of the former. All I am saying is give Hargeisa a chance.

It is also International Museum Day, organised by the International Council of Museums, this year with the theme of “The Future of Museums in Rapidly Changing Communities”. Go to a museum. They’re brilliant.

Factoids

English, Scottish and British monarchs have tended not to be particularly adventurous in their selection of personal and regnal names. We have had eight Henrys and Edwards, seven Jameses, six Georges, four Malcolms and Williams and so on (though beginning the numbering at the Norman Conquest in 1066 is wholly arbitrary: there are at least two, arguably three pre-Conquest Edwards, two Edmunds and two Harolds who should by any measure be included). The last monarch to use a wholly novel name was Victoria in 1837, before her George I in 1714 and before him Anne in 1702. But the paths less travelled sometimes throw up some curious and unlikely possibilities. Edward I, King of England from 1272 to 1307 and known as Longshanks and “the Hammer of the Scots”, had at least 17 legitimate children with his two wives, but around half died in infancy or youth, and no name is recorded for two of them. He was eventually succeeded by his sixteenth child and fourth son, Edward II, but he had three male heirs who predeceased him. Two were John and Henry, unimaginative enough, but from 1274 to 1284, the heir to the throne of England was the young Alphonso, Earl of Chester. He was 11 months old when his brother Henry died (aged six), and was heir apparent until his death at the age of 10 in August 1284, four months after Edward’s birth. The cause of death is uncertain, though seems to have been sudden, and he was buried in the Chapel of St Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey, while his heart was interred at the Dominican priory at Blackfriars, just south of what is now Carter Lane, near Ludgate Hill. So, had events transpired differently, Edward I’s death in 1307 could have seen the accession of King Alphonso I of England.

When we talk about a regency in the context of the British monarchy, we tend to think of George, Prince of Wales, who was Prince Regent 1811-20 under the terms of the Care of King During his Illness, etc. Act 1811, during the incapacitation of his father George III. He eventually succeeded to the Crown as George IV in 1820. (There are a dozen other pieces of legislation relating to the necessity of regent if the monarch is under age but none has been invoked since 1820.) However, the Succession to the Crown Act 1707 made provision that, if the new monarch were not in Britain at the death of Queen Anne, the government would ad interim be entrusted to between seven and 14 Lords Justices; this was entirely possible, as the succession had been settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover, granddaughter of James VI and I, and her Protestant descendants. Seven were named in the act, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor, the Lord High Treasurer, the Lord President of the Council, the Lord Privy Seal, the Lord High Admiral and the Lord Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench. The next monarch could nominate another seven, notifying the Privy Council of England in writing (and in triplicate), and it was treason to open the nominations without authorisation or to fail to ensure their delivery to the Privy Council. The Lords Justices were free “to use, exercise, and execute all powers, authorities, matters, and acts of government, and administration of government, in as full and ample manner as such next successor could use or execute the same, if she or he were present in person”. They were not permitted to dissolve Parliament without express direction from the monarch, or to grant Royal Assent to bills which repealed or amended various statutes on the religious settlement.

Sophia of Hanover died on 8 June 1714 and was succeeded as heir to Queen Anne by her son, Georg I Ludwig, Elector of Hanover. Anne then died on 1 August, and Georg was proclaimed King of Great Britain, but he was in Germany, which engaged the provisions of the Succession to the Crown Act. The Lords Justices named in the act were therefore Thomas Tenison, Archbishop of Canterbury; Lord Harcourt, Lord Chancellor; the Duke of Shrewsbury, Lord High Treasurer; the Duke of Buckingham and Normanby, Lord President of the Council; the Earl of Dartmouth, Lord Privy Seal; and Sir Thomas Parker, Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, who acted as the senior Lord Justice. There was no Lord High Admiral, as the office had reverted to the Queen in 1709 and been placed in commission, so the Earl of Strafford, First Lord of the Admiralty, acted instead.

In addition, King George I added Sir William Dawes, the Archbishop of York; the Duke of Somerset; the Duke of Bolton; the Duke of Devonshire; the Duke of Kent; the Duke of Argyll, Commander in Chief, Scotland; the Duke of Montrose; the Duke of Roxburghe, Keeper of the Privy Seal of Scotland; the Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery; the Earl of Anglesey, Vice-Treasurer of Ireland; the Earl of Carlisle; the Earl of Nottingham; the Earl of Abingdon; the Earl of Orford; Viscount Townshend; Lord Halifax, Auditor of the Exchequer; and Lord Cowper. Many of George’s nominations were Whigs and former office-holders, to counter-balance the Tory bent of the late Queen’s ministers. The King eventually arrived in England on 18 September, bringing the tenure of the Lords Justices to an end.

The appointment of Lords Justices to act as collective regents was not unknown. Between 1689 and 1702, and from 1714 to 1837, Britain was ruled by monarchs who also had territorial possessions in continental Europe: King William III was also Stadtholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, while George I, George II, George III, George IV and William IV were Electors (Kings after 1814) of Hanover. This meant that they would from time to time be required to be away from Britain and provision had to be made for the government. When William III went to Ireland in 1690, his wife, Queen Mary II, who was joint sovereign, exercised royal authority under the terms of the Absence of King William Act 1689. After the Queen’s death in 1694, however, William was sole monarch, and when he was absent from the country he began the practice of appointing seven Lords Justices to carry out his duties; this occurred for a few months at a time in 1695, 1696, 1697, 1698, 1699, 1700 and 1701. When George I returned to Hanover in 1716-17, he appointed his son George, Prince of Wales, as Guardian and Lieutenant of the Realm, but their relationship was poor, and he reverted to the practice of appointing Lords Justices during his absences in 1719, 1720, 1723, 1725-26 and 1727. George II nominated his influential queen, Caroline of Ansbach, as Regent for his absences in 1729, 1732, 1735 and 1736–37; after her death he appointed Lords Justices in 1740, 1741, 1743, 1745, 1748, 1750, 1752 and 1755. All of this meant that from 1695 to 1755, Lords Justices exercised royal authority on behalf on an absent monarch 21 times, amounting to nine years in total.

The last period during which Lords Justices executed the functions of government was from 27 September to 8 November 1821, when George IV was absent in Hanover. He appointed 19 Lords Justices:

HRH Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany [heir presumptive to the throne]

Charles Manners-Sutton, Archbishop of Canterbury

The Earl of Eldon, Lord Chancellor

The Earl of Harrowby, Lord President of the Council

The Earl of Westmorland, Lord Privy Seal

The Duke of Montrose, Master of the Horse

The Duke of Wellington, Master-General of the Ordnance

The Marquess of Winchester, Groom of the Stole

The Marquess of Cholmondeley, Lord Steward of the Household

The Marquess of Londonderry, Foreign Secretary [Viscount Castlereagh]

The Earl Bathurst, War and Colonial Secretary

The Earl Talbot, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

The Earl of Liverpool, First Lord of the Treasury [Prime Minister]

Viscount Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty

Viscount Sidmouth, Home Secretary

Lord Maryborough, Master of the Mint

Nicholas Vansittart MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer

Charles Bathurst MP, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

F.J. Robinson MP, President of the Board of Trade and Treasurer of the Navy

Points to note are that Lord Maryborough was the Duke of Wellington’s younger brother, Viscount Sidmouth had previously, as Henry Addington, been Speaker of the House of Commons then Prime Minister and F.J. Robinson would briefly serve as Prime Minister 1827-28 as Viscount Goderich, then in various other cabinet posts as Earl of Ripon.You’ve probably never wondered this but I will tell you anyway. Heads of Oxbridge colleges can go by various titles and it can be hard to remember what office governs each college. In terms of preponderance, there is a substantial difference between the two institutions. The University of Oxford has 13 principals, seven presidents, seven wardens, six masters, three provosts, two rectors and a dean (the last is Christ Church). The University of Cambridge features 20 masters, six presidents, two principals, one mistress, one provost and one warden. So now you know.

Girton College, Cambridge, was founded in 1869 to teach young women, and was granted full college status in 1948. In 1976, it was the first women’s college at Cambridge to become co-educational, and its alumni include Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Baroness Hale of Richmond, Ariella Huffington, Sandi Toksvig, Delia Derbyshire, Margaret Mountford, Dame Karen Pierce, Hisako Princess Takamoto and Baroness Symonds of Vernham Dean. Although its first male graduate students arrived in 1978 and its first male undergraduates in 1979, the college has always (so far) been headed by a woman, though it is not a requirement. However, if and when a man becomes head of the college, he will, under the current statutes, be Mistress of Girton College.

Cambridge still has two women-only houses: Murray Edwards College (formerly New Hall) and Newnham College. Oxford has no single-sex colleges, St Hilda’s College, the last all-female house, admitting male students in 2008. The last men’s college to admit women was Oriel, in 1985.

Moving on… not every television programme can be a smash hit but spare a thought for anyone involved in Australia’s Naughtiest Home Videos. Devised as a racy spin-off from Australia’s Funniest Home Videos, it was a compilation of sexual situations and misfortunes, hosted in typically ribald style by the larrikin’s larrikin, Doug Mulray. The first episode was broadcast on Nine Network on 3 September 1992, and the owner of the network, billionaire Kerry Packer, was watching. (He had sold Nine Network to Alan Bond for $1.2 billion in 1987 before buying it back in 1990 for $250 million, a lucrative switcheroo legendary in Australian media circles.) He did not like what he saw, and told Nine halfway through the episode, “Get this shit off the air!” The network’s employees did as they were instructed, stopped the broadcast and played an episode of Cheers for the remainder of the time slot. The series was abandoned permanently.

“If most writers are honest with themselves, this is the difference they want to make: before, they were not noticed; now they are.” (Tom Wolfe)

“Labour has given up its growth mission”: a quietly stinging piece by Janan Ganesh in The Financial Times, in which he argues partly that the government is guilty of linguistic tomfoolery—however much you may support various policies, from economic growth via net zero to employee rights, they cannot all be your priority or the word “priority” ceases to have any meaning—but also points to a deeper intellectual malaise. Labour, he suggests, cannot seem to see that, while it remains publicly committed to growth above everything else, it is introducing measures which directly contradict and frustrate that objective. That policy disjunction is much more serious than a rhetorical one because it can only end in failure. If you don’t know what you’re doing, you have no way of knowing what you’re doing wrong.

“The Rise of American Bushido”: an absolutely excoriating polemic on Secretary of Defense Rock’s Substack, which condemns the hyper-masculine “warrior ethos” so frequently mentioned by the current Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, as obsessed with killing (or “lethality”), often subordinating purpose to means, and in fact a dramatic departure from the United States’s tradition of the citizen soldier. This culture, he argues, serves to widen the gap between soldiers and civilians, “encouraging a professional military caste isolated from civilian oversight, and glorifying violence as the central expression of national power at home and abroad”. I think it hits the nail on the head and goes to the heart of some of the worst and most troubling aspects of the American military in recent years, the glorification of extreme violence which has often been deeply self-defeating in places like Iraq and Afghanistan; the way Hegseth in particular—though he is completely unsuited for his office in many respects—seems to venerate the killing of enemies and the creation of a warrior caste reeks to me of deep personal inadequacy and a potentially catastrophic mindset. A scintillating read.

“Chapel, chanting and chips”: as many of you know, monasticism was my first academic specialism, or at least its brief reflowering in England in the 1550s, so my eye was drawn to this piece in The Critic in which the Revd Max Bayliss, vicar of Chelsea Old Church, visited the Carthusian monastery of St Hugh’s Charterhouse, Parkminster, and the Benedictine communities at St Augustine’s Abbey, Chilworth, and St Michael’s Abbey, Farnborough. He examines what it is that leads men—as it happens, he visited male communities—give up almost everything worldly to live a communal life of prayer and devotion. Bayliss is clearly sympathetic, as he talks about the pleasure of being able to “step out of a world which is often chaotic and confused into one of meaning and calm”. I am obliged to note that not everyone would find the monastic life full of “meaning”, but equally in fairness he is not engaging in frantic evangelism. It is an interesting insight because, for all that the level of interest is talked up, I suspect the vast majority of people in Britain, including most Christians, would find the nature of the cloistered life simply very weird and unfamiliar; it kicks against teh pricks, to use a good Biblical phrase, not just of modern materialism but individuality, freedom and autonomy, representing in some ways an almost complete abnegation of the self and a complete submission to God. Traditional monastic communities may, as Bayliss says, “offer stability and solace in a mad world” for some people, but that seems limitative. No doubt many who embrace the enclosed life do find themselves achieving a more satisfying and complete relationship with the divine, and intercessory prayer remains part of the monastic routine: prayers for the dead were the motor of pre-Dissolution monasteries, vital to help those who were enduring purgatory. Nevertheless, I think it is a very specific appeal to a very specific group (though I wish them all well).

“Trump moves on before his deals can be exposed as meaningless”: a trenchant column in The Daily Telegraph by former Defence Secretary Sir Ben Wallace, making the very persuasive case that President Donald Trump cannot bear to be seen as the losing contender in any competition, never takes responsibility for anything that goes wrong and simply moves on—amid, I would suggest adding, a smokescreen of lies, poses and petty insults—before the weakness and inadequacy of his so-called “achievements” are fully exposed. I think Ben’s right to suggest that Trump is bored of Ukraine now and is itching to explore new “deals”, and that he is weirdly and alarmingly in thrall to strongmen like Vladimir Putin; and I think he makes another important point that the United States, for all its military, economic and financial dominance, cannot afford simply to turn a blind eye to world opinion. Trump is creating a great reservoir of uncertainty, distrust and hostility because of his bombastic, self-centred approach to world affairs, and the day will come, probably sooner rather than later, that such a high-handed and dismissive approach to other countries eventually returns to trip you up.

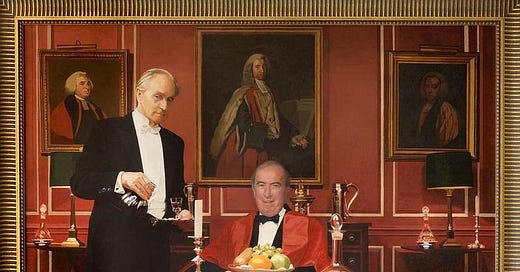

“The art of the political lunch”: Bruce Anderson is a political institution: Orcadian by birth, educated at Campbell College, Belfast, home to the cream of Ulster (“rich and thick”), and Emmanuel College, Cambridge, at both of which he was a contemporary of Lord Bew, he was a Marxist in his youth and now is… not. He writes a wine column for The Spectator, which is very much on-brand, and can be found ensconced in the Travellers’ Club (and elsewhere, no doubt), always ready to pronounce on affairs of the day. I was once in a conversation which featured the Andersonian sally “I remember saying to George Bush during the 1988 presidential election…” Here he talks fondly of the now-lost ritual of the expansive political lunch, not an occasion for detailed policy discussion but for low gossip and high-level historical sweep. For what it’s worth, I think the mean-minded, mealy-mouthed parsimony of contemporary political culture has lost something valuable in the decline of political lunching and dining, though it survives in pockets. But this is a warmly nostalgic recollection from a true connoisseur.

“Gatsby’s Secret”: I include this essay from Wesley Lowery’s Substack not because I agree with it—I’m pretty sure I don’t, quite vehemently—but because it is thought-provoking, and it is the laziest of stances only to read that with which you know in advance you will agree. Lowery takes as his starting point a theory proposed in Carlyle Van Thompson’s The Tragic Black Buck: Racial Masquerading in the American Literary Imagination (2004) that the title character of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is, in fact, a black man passing as a white man in East Coast society. I’m extremely dubious of this kind of literary archaeology, through which scholars and critics pick over fragments and amplify tiny elements out of all proportion, and it’s a method of argumentation that is framed in a way difficult to refute. Lowery tells of Carlyle challenging his students to show the proof that Jay Gatsby is white: “‘And they were stunned,’ he recalled decades later. ‘They could not show me.’” How many volumes in the Western canon contain proof that a leading character is white? Yet overwhelmingly we know them to be intended as such. (This kind of self-absorption was revived a few years ago over the racial identity of Hermione Grainger in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.) You can read The Great Gatsby as a racial allegory if you like, and don’t let me get in your way; but I’ve no earthly reason to think that’s what Fitzgerald intended, or that, if he had, he’d have made it quite so veiled and mysterious that only professors of literature would perceive the truth.

“Leaders should do more to be likeable”: I include this article from The Financial Times by communications coach Dr Kate Mason because a few elements of it struck me as frequent (and, I think, negative features) of the sprawling field of leadership and coaching. Her fundamental point is sound: we diminish the idea of likeability in leaders because we equate it with weakness or malleability, a feeling that someone who is likeable will do anything to please. It is, as she says, “seen as shallow or performative; not something serious leaders should concern themselves with”. Clearly a leader who is liked may well be more effective than one who is loathed, and I think we do sometimes fetishise toughness and a certainly brutality, nodding to the principle associated with Caligula of oderint dum metuant, “let them hate, so long as they fear”. On the other hand, one example she cites, of baristas at Starbucks being encouraged to write messages on customers’ cups, made me shudder: does that actually appeal to people? I also have reservations about some of the evidence she cited; “of 50,000 leaders, only 27 of those rated in the bottom quartile for likeability were also rated top for overall leadership effectiveness”. Well, perhaps, but that is proof of nothing except correlation. Mason also cited former New Zealand Prime Minister Dame Jacinda Ardern (not everyone’s tasse de thé, it must be said) as saying “I refuse to believe that you cannot be both compassionate and strong”. Again, perhaps, but compassion and likeability are not synonymous. I just had a strong feeling that it was juggling words, making qualified judgements seem more absolute than they were and setting up a kind of straw man. But perhaps I am too harsh.

A thought to end

As I recommended some weeks ago, I’ve been reading When The Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines, the memoir of the great Graydon Carter. He co-founded the satirical magazine Spy in 1986, edited Vanity Fair from 1992 to 2017 (taking over from Tina Brown) and in 2019 launched Air Mail, a weekly newsletter for “worldly cosmopolitans”. It is rollocking, star-packed read and a fascinating insight into a lost world of journalism and publishing, but at the end of the book he offers a few light-hearted lessons for life which he had developed over his 75 years, one of which is “to be the dumbest person in the room”.

I know what he means; after all, as he notes, “what is the future in being the smartest person in a working group? Who are you going to learn from?” Obviously we could debate endlessly the meaning of terms like “dumb”, “smart”, “intelligent”, “clever”, “wise” and so on, but that is for another time. Let’s just agree to have a slightly woolly but consensual idea of how we see that spectrum. But I think it’s an interesting approach, if you take it seriously rather than as an extended exercise in false modesty and self-deprecation.

I will certainly say that I have known, worked with, been friends with and loved some of the most jaw-droppingly brilliant, intelligent, erudite and perceptive people. I will refrain from citing family or close friends, because that becomes a spiral of anxiety about whom you have included and whom you have omitted. Outside that small circle, I would certainly point to Sir David Natzler, Clerk of the House of Commons 2014-19 and my boss when I worked in the Public Bill Office, a man of fearsome, penetrating but sometimes unforgiving intelligence, with a mind which works at a phenomenal speed, retains reams of information and can focus dauntingly and strip away extraneous elements to get to the heart of an issue. In his younger days, I former colleagues in the House told me, he could be savage in his application of brainpower and suffered fools not at all; by the time I knew him at all well, it was more the case that you simply had to be prepared for intellectual jousting. David likes an argument and doesn’t pull his punches, but if you survive the encounter you know you’ve been operating at a pretty high level.

Alan Sandall was another colleague in the Public Bill Office, formally Clerk of Grand Committees by the time I worked alongside him and reaching the end of his 40-odd years in the House of Commons. Alan was a master of parliamentary procedure—I think most colleagues would have agreed that by the time he retired in 2010 he was unmatched in his expertise of how the House worked in technical terms, but he had also developed a sensitivity for the politics of Parliament. He once summed up the role of clerks to me as being (I can’t claim this is verbatim) to help MPs do what they want to do, within the rules of the House. He possessed—possesses, as he is still very much with us and can sometimes be found volunteering in the Oxfam bookshop in Chiswick—a clear and logical mind which could break down problems into component parts to find solutions, and which was effortlessly able to discern the logical thread which runs through the legislative system, of bills, amendments, new clauses, amendments in lieu and all the moving parts which make law. And he was supreme at maintaining all of that within a calm composure, on the grounds that agitation is never an aid to problem-solving or insight. I don’t always manage to practise it, but that sense of calmness, of methodical order especially in a crisis, is something I reach for.

I am forever (unapologetically) championing Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman of Ogilvy Group, in these despatches, and I’m lucky enough to know him a little. What I find dazzling and so admirable about Rory (apart from his fundamental niceness and generosity of spirit) is his creativity, his apparently effortless ability to approach issues from a perspective you would never have considered, or to make some observation that turns everything profitably and illuminatingly on its head. (If you haven’t read his book Alchemy, then you really should. It’s a triumph.) Insofar as In have any rules for life, or a kind of “Wilsonian” approach to politics, business or anything else, an important part of it is “thinking round corners”, as I call it internally: trying to find a new way to attack a problem or drawing on some other case or discipline to open up new possibilities. Rory is also one of those people who has an inexhaustible appetite for learning, something I’d put very close to the top of the list of characteristics an intelligent person should have. The world is fascinating.

This is very much not a what-little-ol’-me routine. I will say, with due expectation of mockery or ribbing, that I think I’m clever by normal standards, I have a retentive memory and that allows me to put together ideas and issues that some people don’t. I’m always, I hope, curious, and I’m able to communicate ideas and arguments quite well and entertainingly, perhaps persuasively. Unquestionably, for each of my talents, I know people who are better at them than I am: I know people who are better read, more analytical, have a better memory, are more experienced, are better judges of character. But I think I combine a lot of qualities in a way which people find useful and interesting.

But, just to end of Carter’s observation, when it comes to collaboration, partnership in any field of endeavour, or even just life in general, there’s a lot to be said for hanging around with people who are better at things than you. Perhaps “the dumbest person in the room” is hyperbole, but I would hate to be surrounded, personally or professionally, by people who didn’t challenge me, make me think a bit harder and from whom I can learn. And you should always be learning. Always always always.

Now and again in the affairs of men…

… Austen Chamberlain told the Conservative Party conference in 1921, there comes a moment when courage is safer than prudence, when some great act of faith, touching the hearts and stirring the emotions of men, achieves the miracle, that no arts of may be passing before our eyes now that we statesmanship can compass. Such a moment meet here. I pray to God with all my heart and soul that each of us to whom responsibility is brought may be given vision to see the faith and to act with courage and persevere.

Until next time.