Sunday round-up 13 July 2025

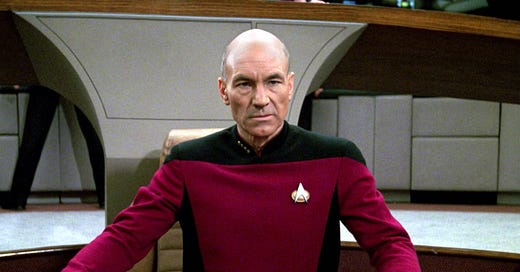

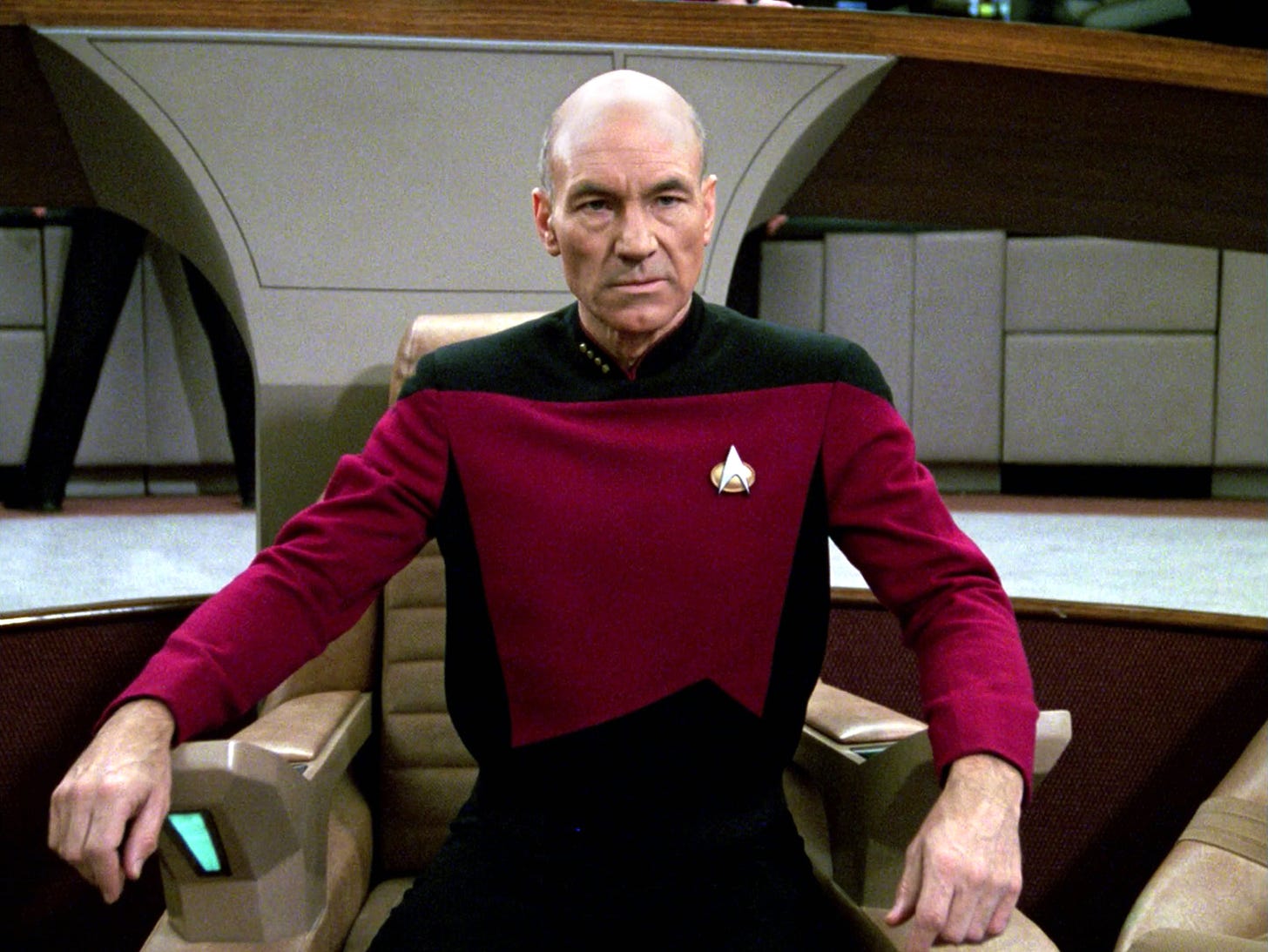

Birthday cake? Make it so for Sir Patrick Stewart, Harrison Ford and Ian Hislop, while Montenegro marks Statehood Day recalling the end of the Congress of Berlin

Parish notice: as some of you will be aware, I have been named Senior Fellow for National Security at the Coalition for Global Prosperity. I’m delighted to take on the role and look forward to working with the team on the full policy spectrum of the UK’s security, at home and abroad. I remain Contributing Editor at Defence On The Brink, weekly columnist at City A.M. and writer/commentator/observer/gadfly, so you need have no fear of losing sight of me.

Preparing for the bumps today are actor, director and producer Sir Patrick Stewart (85), Hollywood legend Harrison Ford (83), singer-songwriter, jingle-jangle guitarist and Byrds co-founder Roger McGuinn (83), blast-from-the-past journalist and That’s Life! trouper Chris Serle (82), genius-level puzzle inventer Ernö Rubik (81), actor and under-the-patio soap star Bryan Murray (76), under-rated, smooth-as-silk racing driver Thierry Boutsen (68), director, producer and screenwriter Cameron Crowe (68), venerable satirist and Private Eye editor Ian Hislop (65), perennially unlucky Formula One driver Jarno Trulli (51) and former N-Dubz mononym enthusiast Tulisa (37).

Gone too soon, or not soon enough, or just at the right time are corrupt-even-by-the-standards-of-the-16th-century-curia Francesco Cardinal Armellini Pantalassi de’ Medici (1470), deeply weird Welsh mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, occultist and alchemist John Dee (1527), Holy Roman Emperor, contributor the Peace of Westphalia, composer and musician Ferdinand III (1608), Confederate general, innovative cavalry leader, prominent slave-trader and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821), Fabian Society stalwart, founder of The New Statesman and Labour cabinet minister Sidney Webb, Lord Passfield (1859), pioneering archaeologist, Egyptologist and folklore expert Margaret Murray (1863), hotelier, investor and significant RMS Titanic non-survivor John Jacob Astor IV (1864), Roman Catholic priest, child welfare activist and founder of not-what-it-sounds-like Boys Town Fr Edward Flanagan (1886), art historian, curator, writer and broadcaster Lord Clark (1903), two-time Formula One World Champion Alberto Ascari (1918), French cabinet minister, President of the European Parliament and Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen survivor Simone Veil (1927), Bill Haley-supporting bass player Al Rex (1928), versatile actor and Jackie Brown star Robert Forster (1941) and rapper and possible pseudonym-user MF Doom (1971).

Redrawing the map of Europe

On this day in 1878, the plenipotentiaries of seven major powers gathered for a final time in the Reich Chancellery at Wilhelmstraße 77 in Berlin, the official residence of the Chancellor of the German Empire, Lieutenant General Otto Prince von Bismarck. He had become the chief minister of a unified German state in March 1871, but retained the offices he had previously held, Minister-President and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Prussia. At 63, he was therefore in almost-complete control of foreign and domestic policy for the new German Empire; although the Emperor, Wilhelm I, had considerable powers at his disposal, he left the business of government largely to his Chancellor (though he once remarked in private, “It is not easy being Emperor under such a Chancellor).

For a month, Europe’s leading statesmen had been gathered at Bismarck’s offices for the Congress of Berlin, with delegations from the six major powers as well as the Ottoman Empire:

German Empire: Prince von Bismarck; Bernhard Ernst von Bülow, Prussian State Secretary for Foreign Affairs; Chlodwig Prince von Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, Ambassador to France

Austria-Hungary: Count Gyula Andrássy, Minister of the Imperial and Royal Household and Foreign Affairs; Count Alajos Károlyi de Nagykároly, Ambassador to Germany; Baron Heinrich Karl von Haymerle, Ambassador to Italy

French Republic: William Waddington, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Charles Comte de Saint-Vallier, Ambassador to Germany; Félix Hippolyte Desprez, Director of Political Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Kingdom of Italy: Count Luigi Corti, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Count Edoardo de Launay, Ambassador to Germany

Russian Empire: Prince Alexander Gorchakov, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Count Pyotr Andreyevich Shuvalov, Ambassador to the United Kingdom; Count Pavel Ubri, Ambassador to Germany

United Kingdom: the Earl of Beaconsfield, Prime Minister; the Marquess of Salisbury, Foreign Secretary; Lord Odo Russell, Ambassador to Germany; Lord Lyons, Ambassador to France

Ottoman Empire: Alexander Karatheodori Pasha, Commissioner of the Porte; Sadullah Pasha, Ambassador to Germany; Marshal Mehmed Ali Pasha, Chief of Staff of the Army; Mkrtich Khrimian, former Patriarch of Constantinople and representative of the Armenian people

In addition, four Balkan states, the Kingdom of Greece, the Principality of Serbia, the Principality of Romania and the Principality of Montenegro, sent representatives to the Congress, as did the Albanian population, concentrated in the Vilayets of Janina and Scutari of the Ottoman Empire.

Bismarck had convened the Congress of Berlin because of mounting tensions in Europe after the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 and the signing of the Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano in March 1878. The Russian signatories, at least, had regarded it as nothing more than a holding agreement until a more permanent settlement of conflict in the Balkans could be agreed with the involvement of the other major European powers. It established a largely autonomous Principality of Bulgaria with a Christian government and its own army; in theory Bulgaria was a tributary of the Ottoman Empire, which had controlled the territory for 500 years, but in practice it was an independent state closely allied to Russia.

This caused alarm to other European nations who did not want to see such expansion of Russian influence, especially as the borders of Bulgaria as drawn at first gave it ports on the Mediterranean Sea which might by used by the Russian Navy. The United Kingdom in particular felt its interests were compromised. The Royal Navy had sent the Mediterranean Fleet under Vice-Admiral Geoffrey Hornby to Constantinople in a show of strength in February 1878 to deter Russian encroachment into the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, and Britain was prepared to contemplate war with Russia if it occupied the Ottoman capital.

The purpose of the Congress, therefore, was to achieve a settlement in the Balkans which appeased each of the great powers and averted the likelihood of another conflict. Their aims were disparate: Britain and France wanted to keep Russia out of the eastern Mediterranean—which in effect meant propping up the ailing Ottoman Empire—while Russia wanted to expand its access to warm-water ports and strengthen nascent Bulgaria. Austria-Hungary wanted to exercise its territorial dominance in the Balkans, while Germany wanted to prevent the Habsburg monarchy, with which it was allied, from going to war.

Britain was at her imperial pomp, and her 73-year-old Prime Minister equally so. The Earl of Beaconsfield—Benjamin Disraeli until his ennoblement two years before—had arranged the purchase of the Khedive of Egypt’s shares in the Suez Canal Company in 1875, and had recently managed the Royal Titles Act 1876 through Parliament which had given Queen Victoria the style “Empress of India”. Just days before the Congress of Berlin began, the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire had secretly agreed the Cyprus Convention, under which the island remained formally under the suzerainty of the Sultan but he “consents to assign the island of Cyprus to be occupied and administered by England”. Britain now had a firm grip on the sea route to India through the Suez Canal and a military base in the eastern Mediterranean from which to protect it.

Dizzy was ailing as well as old. His poor health had made him consider giving up the premiership two years before, but his likely successor, the Foreign Secretary the Earl of Derby, had persuaded him to remain in office, feeling he could not manage the Queen in the way Disraeli had if invited to form a government; as a compromise, Disraeli had accepted a peerage and left the strains of the House of Commons for the less arduous surroundings of the House of Lords. When asked how he was finding his new surroundings, he told a friend “I am dead; dead but in the Elysian fields”. The leadership of the government in the Commons was left to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Stafford Northcote (one of the co-authors of the Northcote-Trevelyan Report of 1854 which created to modern permanent civil service).

But by the time of the Congress of Berlin, there was a new Foreign Secretary, one who would conduct most of the detailed business on the British government’s behalf. Derby was much less hawkish towards Russia than the Prime Minister, and generally less inclined to contemplate war: in January 1878, when the cabinet agreed in principle that the Mediterranean Fleet should force its way through the Dardanelles, he offered his resignation in protest. Disraeli allowed him to withdraw it when the naval action proved unnecessary, but it merely delayed the inevitable: in April, the government agreed to call up the Army Reserve and to consider deploying units of the Indian Army to Malta with the possibility of then moving them to the Balkans. Derby resigned again, and this time it was accepted. He would join the Liberal Party within two years.

In his place, Disraeli turned to the taciturn, aristocratic and reactionary Secretary of State for India, the Marquess of Salisbury. A towering figure at 6’4”, bulky in later life, balding and with a bushy beard, he was a strange, impenetrable character: fiercely intelligent and genuinely intellectual, devoutly Anglican, shy, neurotic, depressive, often fatalistic but firm and determined in policy-making. He was a third son, but his eldest brother, James, Viscount Cranborne, died unmarried in his early 40s, while another brother, Lord Arthur Cecil, died in infancy. Salisbury was Member of Parliament for Stamford from 1853 to 1868 but succeeded his father in the marquessate and would spend his remaining 35 years in the House of Lords. He would be Foreign Secretary four times and Prime Minister three (1885-86, 1886-92, 1895-1902), the dominant Conservative politician of his era.

Bismarck concluded early on that Germany could derive little advantage from the Congress so acted as an impartial host-cum-chairman, but his temper was foul: he had no wish to be in Berlin at the height of summer, and his stewardship was peremptory, to say the least. Speeches were often cut off, and the delegates of the small Balkan countries, whose territories were the stakes for which the Great Game was being played, were barely allowed to participate at all.

The Treaty of Berlin, signed this day in 1878, was a mixed bag. The Principality of Bulgaria was preserved, still under nominal Ottoman suzerainty, but it was much smaller than its previous form and a second autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia was carved out of the territory. Russia recovered Southern Bessarabia, which it had lost after the Crimean War, and Romania, Serbia and Montenegro were all confirmed as independent principalities. Bosnia and Herzegovina were granted to Austria-Hungary, although remaining de jure under the Sultan’s jurisdiction, while the Ottoman Empire retained Macedonia.

For the Russians, it was a deeply disappointing outcome after a decisive military victory over the Ottomans, while the Sultan’s crumbling empire was propped up just enough to satisfy opponents of Russian expansion. Tensions remained between Greece and the Ottomans, Italy found no major advantage and the strengthening of Austria-Hungary in the Balkans was a blow to the cause of pan-Slavism. Perhaps the biggest winner in the short term was Britain: despite not having been involved in the Russo-Turkish War, she added had added Cyprus to her domains, seen the Russians thwarted and the Ottomans weakened without collapsing and safeguarded the approach to India. It was an auspicious beginning for the new Foreign Secretary, who, along with the Prime Minister, received the Order of the Garter in recognition of the diplomatic triumph.

It might be noted that Austria-Hungary’s control over Bosnia and Herzegovina would have serious consequences 36 years later, when the heir to the Habsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, visited Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. He would not leave alive.

Greater love hath no man than this, than he lay his friends down for his life

It is appropriate that newspapers are carrying stories of the Prime Minister contemplating a cabinet reshuffle to “reimpose his authority” and reinvigorate his government (after a year in office!), since today is the anniversary in 1962 of one of the most famous—an ineffective—cabinet reshuffles in modern political history: the “Night of the Long Knives”.

By the summer of 1962, it was hard to argue that things were going well for the government. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had been in office for five-and-a-half years, and, even if it had been through shameless and cynical showmanship, he had dragged the Conservative Party from its post-Suez Crisis slump to a third general election victory in October 1959 with a commanding majority of 100. The government’s slogan had been “Life is better with the Conservatives, don’t let Labour ruin it”, and Supermac, as Victor Weisz had dubbed the Prime Minister in The Evening Standard in 1958, initially satirically, was at the top of his game. The Labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, was highly intelligent and able but regarded as dry, and had none of Macmillan’s flair for publicity; Aneurin Bevan’s remark in 1954 about the need for “a kind of desiccated calculating-machine who must not in any way permit himself to be swayed by indignation” was widely taken to refer at least in part to Gaitskell, then Shadow Chancellor.

Now, though, Macmillan was 68 years old, and the Old Etonian former Guards officer was beginning to seem out of touch. The Swinging Sixties were not quite underway, the Beatles’ debut single Love Me Do only being released in October 1962, but Coronation Street was regularly seen by three-quarters of television viewers, British theatre and literature had been convulsed by the “Angry Young Men” like John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe and Harold Pinter and Beyond the Fringe had begun the satire boom of the early 1960s, of which Macmillan would be a key target.

Politically matters were little rosier for the government. In 1961, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Selwyn Lloyd, had been forced to respond to a poor balance of payments situation by imposing a seven-month wage freeze; inflation had risen from one per cent on 1960 to 3.45 per cent the following year and would rise again to 4.2 per cent in 1962; productivity, while increasing steadily, remained stubbornly lower than for European competitors; and the UK’s formal application to join the European Economic Community, made in July 1961, was domestically controversial and making slow progress in Brussels.

The sense of malaise and lack of direction was having concrete political effects. In March 1962, following the appointment of the sitting Member, Donald Sumner, as a County Court judge, the Liberal Party’s Eric Lubbock had won the Orpington by-election with a swing from the Conservatives of 22 per cent. Such a dramatic reversal in what was considered a safe suburban Tory seat was shocking, and made many Conservative MPs in similar constituencies deeply anxious. Macmillan resolved that drastic action was needed, and, like so many Prime Ministers before and since, decided that a far-reaching reconstruction of his ministerial team was the solution.

Since economic policy was believed to be the major factor driving voters to switch from the Conservatives to the Liberals, the central objective of the planned reshuffle was to remove Selwyn Lloyd. In a sense, this was deeply unfair: Lloyd was an able and intelligent man, a successful, methodical barrister and a meticulous staff officer who ended the Second World War an acting brigadier, but he lacked dynamism and vision, and the impetus behind the government’s economic policy was Macmillan rather than his Chancellor. He was also conspicuously loyal and well-regarded, if perhaps in a slightly patronising way, by his parliamentary colleagues, as well as gaining sympathy for his lonely, enforced bachelor lifestyle following his divorce in 1957 (he sometimes tried to persuade civil servants to join him at the cinema on Saturday afternoons).

However, Lloyd was nearing 58, and looked it. He had been in office continuously since 1951, and before his move to the Treasury in 1960 had spent nearly five years as Foreign Secretary, a job he neither liked nor excelled at. As a replacement, Macmillan was sizing up the 45-year-old Colonial Secretary, Reginald Maudling, a formidable intellect who had been a junior Treasury minister from 1952 to 1955 and who, although his degree was in classics, had developed relevant expertise as head of the economic section of the Conservative Research Department in the immediate post-war years. He was a sociable, clubbable man, very different from Lloyd, a bon viveur who had an easy rapport with journalists, although by the early 1960s he was already noticeably more effective before lunch than after it. Most importantly, he shared Macmillan’s vision of the Keynes-influenced, Butskellite economic consensus, with employers, trades unions and government cooperating to manage a stable economy with very low unemployment.

Macmillan’s desire to bring in some new, more energetic ministers from the Conservative benches, and to construct a government which would be ready to face a general election which had to be held no later than October 1964, was not in principle a bad one. He discussed his plans with the party chairman, Iain Macleod, and his long-time deputy, Home Secretary Rab Butler, and they agreed that a reshuffle should be conducted in the autumn.

But telling Rab anything was a hostage to fortune. On 11 July, Butler had lunch with Viscount Rothermere, Chairman of Associated Newspapers which included The Daily Mail (which had recently absorbed The News Chronicle), The Evening News and Star and The Daily Sketch. Notoriously indiscreet, sometimes by accident and sometimes by design, he discussed the planned reshuffle at some length, and inevitably it was then reported in Rothermere’s titles the following day, 12 July. Macmillan had been bounced by his deputy’s inability to keep secrets, but decided to press ahead and make the best of the situation.

That evening, Lloyd was called to Admiralty House on Horse Guards Parade, where Macmillan had been based since 1960 after extensive rot and instability had been discovered in 10 Downing Street. Ideally the Prime Minister would have made Lloyd Home Secretary, as he was moving Butler on after more than five years in post, but Lloyd had made it clear to Macmillan long before that he opposed capital punishment and therefore could not properly exercise the royal prerogative of mercy on behalf of the Queen, one of the Home Secretary’s duties. Having been Foreign Secretary and Chancellor, there was no obvious other portfolio for Lloyd to be offered, and so, after a fraught and distressing 45-minute encounter, he was sacked.

The next day, Friday 13 July, Macmillan proceeded with the rest of the extensive reshuffle. Apart from Lloyd, six other ministers were dismissed, many of them in dismay or anger. The Lord Chancellor, Viscount Kilmuir, a political heavyweight who never underestimated his own value, complained he was let go with less notice than a cook; Macmillan observed that it was easier to find good Lord Chancellors than it was good cooks. His promotion to an earldom a week later was scant consolation. Harold Watkinson, Minister of Defence, was told that the Prime Minister needed to make space for younger talent, only to be succeeded by Peter Thorneycroft, half a year older than he was. The powerfully ambitious but now largely forgotten Sir David Eccles, Minister of Education, would only agree to a move if he became Chancellor, but was offered President of the Board of Trade, an office he had already held in 1957-59. As he was also on his second stint as Minister of Education (1954-57, 1959-62), it was clear his time was up, and he was handed a peerage to soothe the blow.

Lord Mills, Minister without Portfolio, and John Maclay, Secretary of State for Scotland, accepted their fates quietly enough; Maclay had indicated he was ready to leave government at the next reshuffle, though had not expected it to arrive so soon. Dr Charles Hill, Minister of Housing and Local Government, also went without rancour, though he objected to the rushed way in which the changes had been handled. The removal of seven cabinet ministers, a third of the total, in one swoop was extraordinary.

The Night of the Long Knives was not an unmitigated disaster. The average age of the departing ministers was 59, while that of the newcomers was only 50. The 39-year-old Sir Edward Boyle became Minister of Education and looked like a future Conservative star, though he would leave the Shadow Cabinet and the House of Commons in 1969 to become Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds and die of cancer in 1981, aged only 58. John Boyd-Carpenter, an energetic and combative debater, became Chief Secretary to the Treasury, while the intelligent and articulate Sir Keith Joseph, 44, improbably and with wild optimism regarded by some as Britain’s answer to Jack Kennedy, stepped up as Minister of Housing and Local Government.

The flamboyant imperialist Julian Amery—son of long-time cabinet minister Leo Amery, brother of John Amery who was hanged for treason after the war and son-in-law of Macmillan—became Minister of Aviation, and Peter Thorneycroft, who had resigned as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1958, completed his rehabilitation by taking over the role of Minister of Defence and completing the creation of a unified Ministry of Defence in April 1964. Enoch Powell, who disliked Macmillan and whom Macmillan regarded with wary discomfort, remained Minister of Health but was now promoted to the cabinet.

The Spectator enthused about the reconstruction. Its editorial the following week, entitled “Let’s Go”, hailed the new cabinet’s strength and liberalism:

The new administration is strong in intellect, experience, and vigour, with far more weight placed on younger men, and no concessions offered to those who think that a move to the right would save the day for the party and damn the consequences. The liberal wing of the Conservative Party is now unmistakeably in the ascendant, both in the Cabinet and outside it, with no more than the minimum of reassurance handed out to the more cautious and traditionally conservative. The men are there. The progressive force and energy are there. Could Mr Gaitskell’s broken-backed party, even with the assistance of Mr Grimond, provide their equal?

Later in them magazine, the mercurial Henry Fairlie, in an article headed “Macmillan Expects”, called the new cabinet “immensely powerful” and “a powerful, united combination”.

The Cabinet is strong by its sheer intelligence. I am the last person to confuse intellectual with political capacity. But what Mr Macmillan’s Government has lacked from the beginning is a streak of intellectual severity. Mr Butler, Mr Macleod and Mr Maudling, Mr Powell, Sir Keith Joseph and Sir Edward Boyle, their minds fascinatingly different and acting on each other, are capable of supplying this. It is as if Mr Macmillan had at last found out what it was that Trollope missed—and not a century too soon.

It was not a universal view. The parliamentary party felt that Selwyn Lloyd in particular had been poorly treated, and when he entered the Chamber of the House of Commons the following week, he was cheered by all sides. Macmillan’s arrival was greeted in silence. Within two weeks, the Prime Minister told Lloyd that sacking him had been a mistake and he was looking for a way to bring him back, though he never did. (One obvious way to avoid the whole business would have been to appoint Lloyd as Lord Chancellor in place of Viscount Kilmuir, but Macmillan supposedly thought he was not a sufficiently distinguished lawyer.) The former Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden, now ennobled as Earl of Avon, said publicly that he thought Lloyd had been “harshly treated”.

Fundamentally, the Night of the Long Knives did not work. It did not stamp Macmillan’s authority on the government anew, but rather made him look like a panicky old man, sacrificing the reputation he had garnered for “unflappability”. Nor did it kick-start the government’s fortunes, which would continue to be battered by the Vassall and Profumo scandals. By October 1963, Macmillan had resigned, ostensibly because of poor health, and Sir Alec Douglas-Home led the party to defeat (albeit by an astonishingly narrow margin) at the general election of October 1964.

It was the young Liberal MP for North Devon who summed up the grubby political calculations many perceived in Macmillan’s actions. Mordantly reversing the words of John 15:13, Jeremy Thorpe observed, “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life”.

Feast, not famine

It is the feast of St Silas (1st century AD), a companion of St Paul the Apostle who accompanied him to Thessalonica and Corinth; of St Eugenius of Carthage (c AD 505), condemned to death by King Thrasamund of the Vandals for refusing to accept Arianism but with the sentence commuted to exile to Vienne in the Languedoc; of St Mildrith (AD 660-AD 731), daughter of the King of Magonsaete who became Abbess of Minster-in-Thanet; of St Henry II (AD 973-1024), Holy Roman Emperor and Duke of Bavaria who championed the power of the Church and promoted monastic reform; and of St Clelia Barbieri (1847-70), a poor Bolognese girl who founded the Little Sisters of the Mother of Sorrows before dying of tuberculosis and who is invoked by catechists and those mocked for their piety.

In Montenegro it is Statehood Day, commemorating the signing of the Treaty of Berlin in 1878 (see above) when the Principality of Montenegro became the world’s 27th independent state (there are now 195).

Factoids

After the Congress of Berlin (see above), Queen Victoria offered to create Benjamin Disraeli a duke; he had been ennobled as 1st Earl of Beaconsfield and Viscount Hughenden in August 1876. For reasons which are unclear, he declined the offer of a dukedom but accepted the Order of the Garter instead. The Marquess of Salisbury would twice be offered a dukedom by Victoria, in 1886 and 1892, but declined both times. He cited the cost of maintaining the kind of lifestyle expected of a duke, and said that he would rather hold an ancient marquessate than a modern dukedom. In fact the marquessate of Salisbury was hardly ancient: it had been created in August 1789 for James Cecil, 7th Earl of Salisbury, Lord Chamberlain of the Household 1783-1804 under George III.

The earldom of Salisbury was of much greater antiquity. In that creation it dated back to 1605, when James VI and I had bestowed it upon Sir Robert Cecil, Viscount Cranborne, who, as Secretary of State (1596-1612), had been instrumental in the King of Scots smoothly succeeding to the throne of England on the death of Elizabeth I. But there had been four earlier creations of an earldom of Salisbury: 1145 for Patrick of Salisbury, 1337 for William Montagu, 1472 for George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, and 1478 for Edward of Middleham, son of Richard III; and the third creation of 1472 had been restored in 1512 for Margaret Pole, daughter of George Plantagenet, as Countess of Salisbury. The title had been forfeit four times over the years.

Queen Victoria created six dukedoms (and five royal dukedoms) over her long reign, but only four are extant: Cecilia Underwood had married Victoria’s uncle Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, but in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act 1772, making it legally void, so she was created Duchess of Inverness in her own right (she died without issue); the 3rd Marquess of Westminster was created 1st Duke of Westminster, largely because of his vast wealth; the 6th Duke of Richmond and Lennox was additionally created Duke of Gordon as the Queen and her ministers had run out of honours to give him (he was already a duke twice over and a Knight of the Garter); the 1st Earl of Fife was created Duke of Fife twice, in 1889 when he married Princess Louise, Victoria’s granddaughter, and 1900, with a remainder for his elder daughter as his only son had been stillborn and the title would otherwise have become extinct on his death; and the 8th Duke of Argyll, whose title was in the peerage of Scotland, was additionally made Duke of Argyll in the peerage of the United Kingdom, partly for holding political office, partly because he had been a close friend of the Prince Consort, partly because his son, John, Marquess of Lorne, married the Queen’s fourth daughter Princess Louise, and partly (again) because they had run out of honours for a duke who was a Knight of the Thistle and a Knight of the Garter. The dukedoms of Westminster, Gordon, Fife and Argyll are still extant.

In effect, then, Queen Victoria only really created two new dukes, the Duke of Westminster and the Duke of Fife. Disraeli and Salisbury would therefore have doubled her tally. In addition, she offered dukedoms to the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, who held a wide range of government posts between 1806 and 1852; and to the 14th Earl of Derby (three times Prime Minister and father of the Foreign Secretary mentioned above), who said that he preferred to remain 14th Earl of Derby.

Although his father had refused a dukedom, the 15th Earl of Derby is reported to have come close to going several steps better. In October 1862, the King of Greece was deposed by a popular uprising. Otto was a Bavarian prince, second son of King Ludwig I, and at the age of 17 he had been offered the throne of the newly independent Kingdom of Greece by the protocol produced at the London Conference, a meeting of British, French and Russian diplomats convened by Viscount Palmerston. King Otto had been too interventionist, frequently dissolving the Greek parliament and ignoring widespread electoral fraud. After his deposition, there was a strong body of opinion in Greece in favour of offering the throne to Prince Alfred, second son of Queen Victoria, in order to ally Greece more closely with the United Kingdom. A plebiscite showed he was the overwhelming choice, winning a hundred times as many votes as the next contender, the Russian aristocrat Nicholas Maximilianovitch, 4th Duke of Leuchtenberg, but Victoria would not countenance the idea. The Greeks therefore considered inviting a British nobleman to take the crown, and one of their strong preferences was supposedly the 15th Earl of Derby, then still Lord Stanley. Contrary to popular belief, no formal offer was ever made, and the throne eventually went to the 17-year-old Prince William of Denmark, who became King George I of the Hellenes.

As Disraeli and Salisbury refused dukedoms, Lord Lyons (see above), Her Majesty’s Ambassador to France at the time of the Congress of Berlin, three times turned down the opportunity, offered by three different Prime Ministers, to be Foreign Secretary. When William Gladstone won the 1868 general election and became Prime Minister for the first time, he offered Lyons the Foreign Office, given his record as Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States (1858-65) during the challenging years of the Civil War and two years as Ambassador to the Sublime Porte in Constantinople. But he had only been Ambassador to France for 14 months by the time Gladstone’s offer came and he turned it down, to the regret of Queen Victoria; the new premier instead nominated the Earl of Clarendon, who had held the position in 1853-58 and 1865-66, and whom the Queen had come to dislike for his habit of referring to her as “the Missus”.

Lyons was very much in contention for the post again after Derby’s resignation in 1878, and had the strong approval of the Queen, but seems to have pleaded fragile health and Salisbury was appointed. Finally, when Salisbury became Prime Minister for the second time in July 1886, he invited Lyons to be Foreign Secretary after an epic nineteen successful years at the Paris embassy, but he was now nearly 70 and ailing, and would die within 18 months. He had been created Viscount Lyons in 1881, and was promoted to an earldom in 1887 but died before the letters patent were made out, although he is customarily remembered as Earl Lyons. He died without heirs, his titles becoming extinct.

Lyons was not the only man to refuse office when Gladstone formed his first ministry. Former Attorney General Sir Roundell Palmer was offered the position of Lord Chancellor (though that of Lord Chief Justice was also mentioned). Palmer was MP for Richmond, a formidable intellect and one-time leader writer for The Times who preferred equity practice to appearing in front of juries; he was opposed to Gladstone’s proposal to disestablish the Church of Ireland (which would come about under the Irish Church Act 1869) and chose to remain a backbench Member of Parliament to argue against it. However, when Gladstone’s alternative choice, Lord Hatherley, resigned in October 1872 due to failing eyesight, Palmer relented and, ennobled as Lord Selborne, became Lord Chancellor. He oversaw the comprehensive reorganisation of English courts in the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873, and, although he left office when Disraeli became Prime Minister in the following year, he returned for a second term as Lord Chancellor from 1880 to 1885. In 1882 he was created 1st Earl of Selborne but eventually became disenchanted by the Liberal Party’s increasingly radical tendencies, breaking with Gladstone over Home Rule for Ireland, and refused a third term as Lord Chancellor in 1886. He then joined the breakaway Liberal Unionists led by Lord Hartington and Joseph Chamberlain.

Selborne’s son and heir, William, 2nd Earl of Selborne, had a distinguished career as a Unionist politician. He was MP for Petersfield 1885-92 and Edinburgh West 1892-95 before succeeding to the earldom and served under Lord Salisbury (whose elder daughter he had married) as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. In 1900 he was promoted to cabinet rank as First Lord of the Admiralty, before becoming High Commissioner for South Africa in 1905, as well as Governor of the Transvaal and of the Orange River Colony, gaining a reputation for able administration and sound judgement. He retired from his colonial positions when the Union of South Africa was formed in May 1910 but enjoyed a brief return to office as President of the Board of Agriculture from 1915 to 1916.

Fragments of what are believed to be the oldest surviving copy of the Qur’an are kept in the Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham. The manuscript contains parts of surahs 18-20 and are written in an early Arabic script known as Ḥijāzi. The parchment has been radiocarbon dated and identified as being from AD 568 to AD 645 with 95.4 per cent probability; given that tradition says the Prophet Mohammed received the revelations which form the Qur’an between AD 610 and AD 632, and that the Qur’an was codified in its current form under the third Caliph, Uthman, around AD 650, it seems likely that the Birmingham Qur’an must have been among the very earliest copies produced (though some academics challenge the dating and its significance). Still, Birmingham.

“In America journalism is apt to be regarded as an extension of history: in Britain, as an extension of conversation.” (Anthony Sampson)

“How London’s transport network came back to life on 7/7: ‘the fuck-you bus’”: it seems both much less and much more than 20 years since the terrorist attacks on the Tube and bus network on 7 July 2005, yet Monday this week marked just that milestone (I wrote a short piece in commemoration for City A.M.). Here, writer Gareth Edwards, better known as “John Bull”, tells the story of the improvisation, resilience and solidarity which saw Transport for London get the bus service running again in time to help the millions of commuters who had already come into central London before the bombings get home again that evening. Full marks to Peter Hendy, then TfL’s Head of Surface Transport and now Lord Hendy of Richmond Hill, Minister for Rail, and the late Minneapolis-born Bob Kiley, Commissioner of Transport for London, with the backing of then-Mayor Ken Livingstone—while Whitehall hesitated, Hendy and Kiley reasoned that they had not explicitly been told not to restart the bus service, so duly got on with it, and the first bus started its route around 4.00 pm, what one commuter called “that first triumphant, fuck-you bus”. The Blitz spirit at its best.

“A space has opened up in British politics”: in The Financial Times, Camilla Cavendish (Baroness Cavendish of Little Venice) makes the case for a political party which turns down the temperature of politics, presents calm, rational policies to get public finances under control and boost growth. In case you are thinking this was largely Sir Keir Starmer’s pitch, she adds an elusive extra quality, that of competence. “There’s a lot to be angry about,” she notes, “but fixing it requires a level of skill this government has not yet shown.” She spares the Conservatives no criticism, detailing the ways in which the party set fire to its reputation for stability, economic competence and respect for law and order, but also points out the Reform UK leader Nigel Farage “has jettisoned his old libertarianism and made a decisive leftward move on the economy” and “is betting that he can become prime minister by leaning right on culture and left on economics”. Given her ties to David Cameron and other party grandees, one assumes Cavendish hopes this space will be filled by the Conservative Party but she admits she is being optimistic and warns that “it’s going to be a long four years”.

“Trump’s New Favorite General”: I was deeply alarmed when Donald Trump, within weeks of becoming President, dismissed the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Charles Q. Brown Jr, as part of a wider purge of senior military officers. It was reckless politicisation (Brown had been in post not quite 17 months), and it was little reassurance when Trump then nominated as his replacement Lieutenant General Dan Caine, a semi-retired US Air Force officer who was not four-star rank and had never held a major military command; his most senior mainstream position had been Deputy Commanding General of Special Operations Command Central. However, this profile by Mark Bowden in The Atlantic made me feel more optimistic. He portrays an officer whose career has been unconventional but who is utterly dedicated and absolutely clear on his constitutional role and duties as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. Caine has been willing to say publicly things which are not on the Trumpian script, telling a Senate sub-committee that he did not think the United States was being invaded by foreign, state-sponsored forces and that President Vladimir Putin, if victorious in Ukraine, would not be satisfied and would seek further territorial gains. These are early days, but President Trump may not have chosen the kind of politically pliant cipher he thinks.

“Inside the Mind of a Never Trump War Hawk”: in The New Yorker, Isaac Chotiner interviews Eliot Cohen, a former State Department official and influential academic who was among the first to be labelled as a neo-conservative. Cohen is an old-fashioned Republican insofar as he declared himself “never Trump” in an article in The Washington Post in November 2016 and dislikes the President on a personal level. However, he tells Chotiner that he approved of the recent American air strikes on Iran and does not rule out the possibility—indeed, no-one should—that the current administration will occasionally get it right on foreign and defence policy. A very interesting journey through hawkish international affairs circles and the complexity of the current political circumstances.

“Britain ‘must prepare for war with Russia in next five years’”: in her last piece before heading off on maternity leave, The Daily Telegraph’s Defence Editor Danielle Sheridan interviews General Sir Patrick Sanders, Chief of the General Staff from 2022 to 2024. His message is stark: a full-on war with Russia is a strong possibility within the next few years, and the United Kingdom is hopelessly underprepared for the prospect. Sanders is a clever, able, rather sensitive former Royal Green Jackets officer with an enormously impressive career history, but his time in the military did not end entirely happily. It is widely believed he was the Ministry of Defence’s recommendation for Chief of the Defence Staff in 2021, though he was only Commander UK Strategic Command at that point and had held four-star rank for just two years, but Boris Johnson as Prime Minister preferred Admiral Sir Tony Radakin. Sanders then had his term as Chief of the General Staff effectively cut short after two years, having proved too outspoken on the severity of defence cuts. There is a great deal of sense in what he says in this interview, and you can sense his frustration with political leadership: “I don’t know what more signals we need for us to realise that if we don’t act now and we don’t act in the next five years to increase our resilience… I don’t know what more is needed.” I have a slight unease that some of his points are made deliberately dramatic to capture headlines—arguably that is a necessary part of his strategy—and I think his comparison between the UK and countries directly on NATO’s Eastern Flank like Finland, Poland and the Baltic states underplays the obvious difference that, geographically, they are in harm’s way in a sense that Britain is not. Nevertheless, worth reading and absorbing, and Sanders is very well respected. He also has excellent taste in cigars, enjoying a Hoyo De Monterrey Epicure No. 2 during the interview.

“Bring back sedition”: writing in The Critic, Sebastian Millbank argues that we should revive the crime of sedition to deal with those who reject and attempt to subvert lawful authority and undermine the state. Considering the case of recently proscribed group Palestine Action, he proposes that while terrorism legislation was not the most appropriate framework within which to sanction their activity in breaking into a military base and damaging RAF aircraft, it was something which should carry a criminal sanction, and that sedition might fit the bill. It was a common law offence applying to an “intention to bring into hatred or contempt, or to excite disaffection against the person of His Majesty, his heirs or successors, or the government and constitution of the United Kingdom, as by law established, or either House of Parliament, or the administration of justice, or to excite His Majesty’s subjects to attempt otherwise than by lawful means, the alteration of any matter in Church or State by law established, or to incite any person to commit any crime in disturbance of the peace, or to raise discontent or disaffection amongst His Majesty’s subjects, or to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between different classes of such subjects”. The last prosecution was in 1972, and the offence was abolished in England and Wales and Northern Ireland by the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, and in Scotland by the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010. (Sedition by an alien remains an offence under section 3 of the Alien Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919.) Milbank makes an intriguing suggestion that the offence of sedition would not have a deleterious effect on legitimate protest nor force the misuse of terrorism legislation, but allow a very finely calibrated judgement to be made on those who, like Palestine Action, “engage in disruptive and criminal protest that target national defence, and in its own words, seek to ‘bypass our complicit government’”. As ever, I add the disclaimer that I am not a lawyer, but it is something to consider.

“Cuomo and Adams: You Drop Out of the Mayor Race… No YOU Drop Out of the Mayor Race”: in Vanity Fair, Bess Levin examines the extraordinary impending election for Mayor of New York, where young far-left insurgent Zohran Mamdani comfortably won the Democratic Party’s nomination from disgraced former Governor of New York Andrew Cuomo. This puts Mamdani in a strong position for November’s election, since the Democratic candidate has won more than two-thirds of the vote in the past three contests. As Levin notes, New Yorkers now have the extraordinary and unedifying spectacle of Cuomo—who resigned as Governor in 2021 amid a storm of accusations of sexual harassment and misconduct—scrapping with the incumbent Mayor, Eric Adams, who was indicted last year on federal charges of bribery, conspiracy, fraud and two counts of soliciting illegal foreign campaign donations. That both men still feel they are fit to be Mayor is astonishing, and that they feel it so strongly they are willing to run as independent candidates is doubly so. It is this toxic combination of solipsism and chutzpah which has created such promising circumstances for Mamdani. It will be fascinating to see if the Republican Party can find any advantage in this internecine chaos: in 2021, GOP candidate Curtis Sliwa, founder of the Guardian Angels, won 28 per cent of the vote in a city heavily dominated by Democrats, and which has not been carried by a Republican presidential candidate since 1924. But Donald Trump won 30 per cent of the vote last November, the party’s strongest showing since 1988; Sliwa is standing again and must be a very long shot, but if the election becomes a three- or four-way contest, who knows?

“In defence of state banquets”: I’m sure it will surprise no-one that I agreed wholeheartedly with this article in The Critic by Northern Irish writer and photographer Adam James Pollock, in defence of the grand feast which was laid on at Windsor Castle for President Emmanuel Macron’s state visit this week. There has been the usual miserablist, reductive, “think what that money could have bought” criticism from predictable sources—Pollock’s delicate evisceration of Isabel Oakeshott is very enjoyable—and it is a logic which, if followed, would mean governments never did anything in diplomatic terms. Pollock is quite right that hospitality, and good hospitality at that, is an important part of our “soft power” as it is of any nation, and it is generally something we do well. International statesmen are not, to steal Nye Bevan’s phrase, desiccated calculating machines but human being subject to emotion and persuasion. Within the realms of what was possible, I think the government, and the Royal Family, did a pretty good job of receiving the President of the French Republic this week (I wrote about the King’s role for The i Paper on Tuesday), and, yes, it costs money, but in comparison to some public expenditure it is barely a rounding error.

“Lord Tebbit: true blue Thatcherite and scourge of the unions”: there have been many obituaries for Norman Tebbit, who died on Monday at the age of 94, but I think this anonymous piece in The Times (which follows the old-fashioned practice of not attributing its obituaries) is the most comprehensive and balanced. Tebbit was a divisive figure who knew it and revelled in it, and much has been written about his public face, often unpleasant and rude, and his personal kindness (I cannot say as I never encountered him). I do think he was a vital Thatcher ally in the first two-thirds of her leadership, especially as Employment Secretary from 1981 to 1983, and his appalling suffering and that of his wife Margaret after the Brighton bomb in 1984 should elicit the sympathy of anyone. Was he, or could he have been, a likely successor to Thatcher, but for that tragedy? Some have suggested it was almost inevitable he would have succeeded her in 1990 if he and his wife had not been injured; I am not so sure. In his old age, remaining occasionally in the public eye almost until the end, he seemed to become a saddened and downcast figure, one for whom today was always worse than yesterday. Readers will judge for themselves. Of his significance in the politics of that critical decade of the 1980s there can be no doubt.

“Why driving at 80mph won’t save you time”: in his wonderful Wiki Man column for The Spectator, Rory Sutherland returns to a point he makes often, that at higher speeds, going a little faster saves you virtually no time, and the potential disadvantages and dangers begin massively to outweigh any shortening of the journey. Straightforward enough, you might think, but he argues that forgetting or being unaware of this phenomenon has serious public policy consequences: “no one who had studied a paceometer would have demanded HS2 travel so needlessly fast. The distance involved is simply too short for the time-saving to be worthwhile.” Demanding that the trains be capable of 240 mph affected track design, ruled out stopping at potentially popular intermediate stations and offered a saving of only 20 minutes on the journey. “That’s less time than you currently waste on the Euston concourse waiting for them to announce the platform number two sodding minutes before the train leaves.” He raises the possibility of other applications of this method of thinking, and reinforces my belief that, whatever it is you want to do in life, from repainting a bathroom to replacing nuclear weapons, have a conversation over coffee with Rory first. You never know what he might make you consider.

Jukebox jury

“America”, Simon and Garfunkel

“Journey of the Sorcerer”, The Eagles

“Oh I’m A Good Old Rebel”, Hoyt Axton

“All Time High”, Rita Coolidge

“Don’t You (Forget About Me)”, Simple Minds

From the archives: “A Flower for the Graves”

On Sunday 15 September 1963, several members of the United Klans of America planted dynamite attached to a timing device under the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. At 10.22 am, an anonymous man made a telephone call to the church, which was answered by the acting Sunday school secretary, 15-year-old Carolyn Maull. He said simply “Three minutes”. A minute later, the bomb exploded.

The explosion blew a seven-foot hole in the church’s rear wall, and left a crater five feet wide and two feet deep. Several cars parked nearby were destroyed and a passing motorist was blown out of his vehicle. All but one of the church’s stained glass windows were smashed: the remaining window depicted Christ leading a group of young children.

Four girls were killed: Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Denise McNair (11), Carole Rosamond Robertson (14) and Cynthia Dionne Wesley (14). One of the girls was decapitated and her body so badly mutilated in the blast she could only be identified by her clothing and a ring. Addie Mae Collins’s younger sister Sarah (12) had 21 pieces of glass embedded in her face and lost the sight in one eye. Another 13 to 21 people were injured.

Birmingham, Alabama, was a brutally segregated city. Black residents were restricted to specific cinemas, public amenities and water fountains, there were no black police officers or firefighters, and very few black people were registered to vote. At his inauguration on 14 January 1963, Governor of Alabama George Wallace had given a speech which hammered home the message that equal rights and racial integration were no part of his vision for the state.

In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this Earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.

16th Street Baptist Church was, of course, a black church. After the explosion, thousands congregated outside the building, not least to search through the rubble for anyone who might be injured or trapped. Scuffles broke out with the police, and the pastor of the church, the Rev John Cross Jr, loudly recited the 23rd Psalm through a loudhaler in an attempt to maintain calm.

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name's sake. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me. Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over. Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.

Eugene Patterson was Vice-President and Executive Editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a daily newspaper created three years before from the merger of The Atlanta Constitution and The Atlanta Journal. He became editor for both titles in 1956 then took over the combined title in 1960. Every day, he wrote a signed editorial, and the leader he wrote on Monday 16 September 1963, the day after the bombing, was a devastating indictment not just of the men who planted the bomb, “the sick crimnals who handled the dynamite”, but of white Southern society as a whole.

Read the editorial here. Its opening is a sucker-punch:

A Negro mother wept in the street Sunday morning in front of a Baptist Church in Birmingham. In her hand she held a shoe, one shoe, from the foot of her dead child. We hold that shoe with her.

Every one of us in the white South holds that small shoe in his hand.

The editorial hit so hard that Walter Cronkite, the anchorman of CBS Evening News and one of the nation’s most respected television reporters, asked Patterson to read it that evening live on the news.

Just read it.

This time…

… I leave the parting words to a dear friend who lost his wife to cancer horribly early this week.

“We are beyond sad but we keep living on in the memory of her love and in the sure and certain knowledge that we will meet again.”

He is a brave, brave man.