Sunday round-up 12 January 2025

Happy birthday to glittering Bond girl Shirley Eaton, Geordie legend Sir Brendan Foster and thespian's thespian Sir Simon Russell Beale, on the feast of St Benedict Biscop

Presents and cake on this second Sunday of 2025 for a cosmopolitan group including iconic gilded Bond girl Shirley Eaton (88), former professor of law and leading figure of the terrorist group the Weather Underground Bernardine Dohrn (83), Maryhill-born rock singer Maggie Bell (80), first female Senator of the College of Justice Lady Cosgrove (79), former Chair of the London Assembly and Liberal Democrat peeress Baroness Hamwee (78), actor and producer Anthony Andrews (77), athlete, commentator and Geordie legend Sir Brendan Foster (77), Shadowlands playwright William Nicholson (77), novelist and short story writer Haruki Murakami (76), crime novelist Walter Mosley (73), radio host, actor and author Howard Stern (71), journalist and television host Christiane Amanpour (67), co-founder of Roxette and singer-songwriter-guitarist Per Gessle (66), stage and screen actor Oliver Platt (65), actor and theatre veteran Sir Simon Russell Beale (64), reasonably prosperous entrepreneur Jeff Bezos (61), actor Olivier Martinez (59), formerly Beatle-adjacent businesswoman and activist Heather Mills (57), novelist David Mitchell (56), Mercedes Formula 1 team principal Toto Wolff (53), Spice Girl Mel C (51), actress, writer, director and producer Issa Rae (40), singer-songwriter and actress Pixie Lott (34) and One Direction survivor Zayn Malik (32).

Among those who no longer celebrate because they have returned to dust are second Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony John Winthrop (1588), supposed last survivor of the final Byzantine imperial dynasty Godscall Paleologue (1694), Anglo-Irish statesman and author Edmund Burke (1729), Anglo-American Belle Époque portraitist John Singer Sargent (1856), novelist and journalist Jack London (1876), winner of the inaugural Indianapolis 500 Miles Ray Harroun (1879), fighter ace, Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe and Reichsmarschall of the Greater German Reich Hermann Göring (1893), Nazi Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories Alfred Rosenberg (1893), pioneer of intelligence scales David Wechsler (1896), leading slide guitarist and blues musician Mississippi Fred McDowell (1904), first double Academy Award-winning actor Luise Rainer (1910), last Prime Minister and first executive State President of the Republic of South Africa and leading racist P.W. (Pieter Willem) Botha (1916), poetess and prime ministerial spouse Lady Wilson of Rievaulx (1916), US Marine and raiser of the flag on Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima Ira Hayes (1923), ice hockey player and fast food guru Tim Horton (1930), inexplicable all-round entertainer Des O’Connor (1932), lofty blues musician Long John Baldry (1941), heavyweight boxing champion Joe Frazier (1944), actress and producer Kirstie Alley (1951), and talk show host, author and not-much-liked-by-Bill-Hicks Rush Limbaugh (1951).

Amazon prime

Today in 1616, the Portuguese explorer Francisco Caldeira Castelo Branco, Captain of Baía de Todos os Santos (one of the administrative divisions of Portuguese Brazil), anchored his ship in Guajará Bay, at the confluence of the Guamá and Acará rivers. Caldeira had been instructed to explore the mouth of the Amazon river, as yet uncharted by Europeans, and to stop any foreign trading activity by English, Dutch or French merchants.

Like so much exploration of the Americas, Caldeira based his decisions on a misapprehension. Taking Guajará Bay to be the main channel of the Amazon, he struck inland, and about 110 miles upstream he constructed a wooden fort which he named Presépio (“crib” or “Nativity”). A settlement grew up around the fort which was dubbed Feliz Lusitânia (“Lucky Portugal”), and, although French and Dutch merchants continued to trade in the area, neither nation established permanent colonies. The settlement became a municipality named Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão Pará (“Our Lady of Bethlehem of Grao-Para”) in 1621 and then Santa Maria de Belém (“St Mary of Bethlehem”) in 1650; within 18 months of its original foundation it was home to a community of Capuchin friars. In 1655 it was granted city status, and it became the capital of the State of Grão-Pará and Maranhão in 1751.

Belém was the first European settlement in the Amazon. Today it is the capital and largest city of the State of Pará in Brazil, with a population of 1.3 million (which makes it bigger than any British or Irish city except London).

From Charlestown to London town

As investment banker Warren Stephens awaits confirmation as the next Ambassador of the United States of America to the Court of St James’s, as the US representative in London is formally styled, today is the anniversary in 1792 of the appointment of the first such envoy.

(There is a technicality here: from 1785 to 1788, John Adams, one of the Founding Fathers and later second President of the United States, served as America’s “minister plenipotentiary” in London, and was sometimes referred to as the US “ambassador”. He had been recognised as official representative in The Hague by the States General of the Netherlands in 1782, and his house there became America’s first embassy on foreign soil. His time in London, less than a decade after the British colonies had declared themselves independent, was fraught and unsatisfying, and after three years he closed the legation and left, with no successor having been appointed. Since 1792, however, there have been continuous diplomatic relations between the two countries except for the period of the War of 1812.)

Major Thomas Pinckney was a 41-year-old lawyer from Charlestown in the Province of South Carolina, educated at Westminster School, Christ Church, Oxford and the Middle Temple, where he was admitted to the Bar in 1774. He served in the Continental Army during the War of Independence and from 1787 to 1789 was Governor of South Carolina, overseeing his state’s ratification of the Constitution of the United States. He then sat in the South Carolina House of Representatives from January to December 1791.

In 1792, having refused other offers of federal office, Pinckney accepted President George Washington’s appointment as minister to Great Britain and Ireland. In his first years he could make little progress on resolving issues between Britain and America like the impressment of men into military service and the evacuation of British forts in United States territory. Consequently Washington sent John Jay, formerly Minister to Spain, Secretary for Foreign Affairs and Chief Justice of the United States, as a special envoy to London where he negotiated the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, otherwise known as the Jay Treaty.

During his time as Minister to Great Britain, Pinckney also served as his country’s representative to Spain and concluded the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain in 1796. Stepping down that summer, he was chosen by the Federalist Party as running mate to Vice-President Adams in the presidential election later that year, coming third as Adams succeeded Washington as President and the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson came second and therefore assumed the vice-presidency. From 1797 to 1801, Pinckney represented Charleston in the US House of Representatives, stepping down after a second term due to poor health.

Assuming Warren Stephens is confirmed this year by the Senate, he will become the 68th US Ambassador to Great Britain or the United Kingdom. His predecessors, and Pinckney’s successors, include future presidents James Monroe (1803-07), John Quincy Adams (1815-17), Martin Van Buren (1831-32) and James Buchanan (1853-56); famous presidential offspring Robert Todd Lincoln (1889-93) and progenitor Joseph P. Kennedy (1938-40); former US Attorney General and future Secretary of the Treasury Richard Rush (1818-25); former Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin (1826-27); and future Secretaries of State Louis McLane (1829-31), Edward Everett (1841-45), Thomas Bayard (1893-97), John Hay (1897-98), Frank Kellogg (1924-25). The current and outgoing Ambassador, Jane Hartley, was previously United States Ambassador to France and Monaco (2014-17).

First contact

On this day in 1962, American forces undertook their first active combat mission in South Vietnam. A thousand paratroopers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) were airlifted in Piasecki H-21s of theUnited States Army’s 8th Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) and 57th Transportation Company (Light Helicopter) in the imaginatively named Operation Chopper.

The ARVN forces overwhelmed a small Viet Cong stronghold 10 miles west of Saigon and suffered no casualties. It was not a sign of things to come: by the time the conflict in Vietnam ended in April 1975, the United States had suffered casualties of 58,281 killed and 303,644 wounded, while South Vietnam saw around 313,000 military and 195,000 to 430,000 civilian deaths, 1.17 million military personnel wounded and a million taken prisoner.

Happy holy day, neighbouroonie!

It is a quiet day on the festal front: the feast of St Tatiana (3rd century AD), who tended the sick of Rome, refused to offer a sacrifice to Apollo, was blinded, beaten, thrown into a pit with a hungry lion which miraculously left her unharmed, tortured and then beheaded; of St Benedict Biscop (AD 628-AD 690), a Northumbrian aristocrat who founded and was Abbot of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow; of St Ælred of Rievaulx (1110-67), another North Easterner, who was steward of the household of David I, King of Scots, before entering the Cistercian monastery at Rievaulx and rising to be its abbot; St Bernard of Corleone (1605-67), a Capuchin friar from Sicily who joined the Order of Friars Minor after a traumatising duel and was notably austere; and St Marguerite Bourgeoys (1620-1700), a French nun who founded the Congregation of Our Lady of Montreal, ministered to the poor, taught young children and was Canada’s first female saint.

Factoids

I have often written of the lesser known, quirky connections between political leaders, and especially prime ministers, but I have, I realise, neglected the distaff side somewhat, where there are a few nuggets of interest. The Honourable Emily Lamb (1787–1869) was the daughter of the amusingly named Sir Peniston Lamb, 1st Viscount Melbourne (in the peerage of Ireland), who was succeeded in his titles in 1828 by his eldest surviving son, Henry William Lamb. This 2nd Viscount Melbourne, Emily’s elder brother, was twice Prime Minister (1834 and 1835-41), and a mentor to Queen Victoria when she came to the throne in 1837. That same year, Emily’s husband, the 5th Earl Cowper, a Fellow of the Royal Society but an otherwise humdrum aristocrat, died just short of his 60th birthday. The Dowager Countess Cowper then remarried in 1839, to her brother’s Foreign Secretary, another Irish peer, Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston. He would go on to be twice Prime Minister, from 1855 to 1858 and 1859 to 1865, making Emily the sibling and spouse of Irish viscounts who headed the British government. She outlived “Pam” by just four years.

Perhaps the most famously familially linked prime ministers except Pitt the Elder and Pitt the Younger are the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (PM 1885-86, 1886-1892, 1895-1902) and his nephew and direct successor A.J. Balfour (PM 1902-05); Salisbury’s forename was Robert and Balfour’s steep rise up the political ladder is supposed to be the origin of the phrase “Bob’s your uncle” to indicate that something is arranged satisfactorily. They were linked by Salisbury’s elder sister, Lady Blanche Gascoyne-Cecil (1825-72), who in 1843 married the Scottish landowner, businessman and Conservative MP for Haddington Burghs, James Maitland Balfour. They had eight children, of whom the third, the eldest boy, was Arthur James Balfour, whose political career would blossom so fully under his maternal uncle’s patronage.

Lord Salisbury was not hesitant to promote those to whom he was related. When his Unionist government was re-elected at the “Khaki election” of September and October 1900, it was nicknamed the “Hotel Cecil” after a famous London hotel and Salisbury’s family name. Apart from Balfour, who was First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Commons, effectively his ageing uncle’s deputy, Salisbury’s son and heir, Viscount Cranborne, was Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs; his son-in-law, the 2nd Earl of Selborne, was First Lord of the Admiralty; another nephew, Gerald Balfour (younger brother of Arthur), was President of the Board of Trade. In addition, the Chairman of Ways and Means and Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons, James Lowther, was married to one of Salisbury’s nieces, Mary Beresford-Hope, daughter of his other sister Lady Mildred Cecil, and the Prime Minister’s youngest child, Lord Hugh Cecil, was MP for Greenwich.

Clarissa Spencer-Churchill (1920-2021) was the legal daughter of Major Jack Spencer-Churchill, younger brother of Winston Churchill (it was later disclosed that her biological father was a barrister and Liberal MP, Harold Baker). She befriended many of her uncle’s most prominent colleagues and rivals, becoming particularly close to Duff Cooper, Minister of Information (1940-41), Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1941-43) and then Ambassador to France (1944-48), and was the recipient of the last letter he wrote before his death on 1 January 1954. She also developed a relationship with Churchill’s political heir and (eventual) successor, Anthony Eden, and after his divorce from his first wife they married in 1952, when he was in his third stint as Foreign Secretary, impatient to replace the now-ailing and aged Winston as Prime Minister. Clarissa became Lady Eden when her husband was appointed a Knight Companion of the Most Noble Order of the Garter in October 1954, and the following April, Churchill finally though still reluctantly retired and Eden at last reached 10 Downing Street. Clarissa was now the niece of one premier and the wife of another. Eden would resign in January 1957 in the aftermath of the Suez crisis, and was ennobled as Earl of Avon, and the Countess of Avon would live almost another 64 years, dying at the age of 101.

As I was looking over the Salisbury/Balfour government of 1895 to 1905, I noted a number of things, but one was this. When Lord Salisbury constructed his ministry in 1895, he appointed 62 ministers including himself, of whom 19 were in the cabinet. Today’s government has 120 ministers holding 141 posts, and a cabinet at the maximum of 22 full members, with four others “also attending”. Essentially, Sir Keir Starmer has twice as many ministers, with responsibilities over a much smaller jurisdiction but unimaginably more aspects of life than Salisbury’s. Thirty-nine of Salisbury’s 62 ministers hold offices which still exist or are largely identifiable, but some of those which have disappeared or changed beyond recognition include Secretary of State for India, Civil Lord of the Admiralty, Postmaster General, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, First Commissioner of Works, Lord Steward of the Household and Master of the Buckhounds. There was also one woman in a “political” role, the Duchess of Buccleuch as Mistress of the Robes. Although this office had no ministerial authority, until 1901 it would change with the incoming government when there was a queen regnant. What the Marquess of Salisbury would have made of a Minister of State for Energy Security and Net Zero is anyone’s guess.

There has been a Secretary of State for the Home Department (the Home Secretary’s formal title) since 1782, when the Southern Department, responsible for domestic matters, colonies and overseas possessions and foreign affairs in parts of southern Europe, was reorganised as the Home Office, while the Northern Department became the Foreign Office. The original responsibilities of the Home Office were dealing with petitions and addresses sent to the King, advising him on royal grants, warrants, commissions and the exercise of the royal prerogative, maintaining law and order by transmitting instructions from the sovereign to officers of the Crown, lords lieutenant and magistrates, protecting the individual liberties and rights of subjects and matters relating to the colonies. By 1895, when Sir Matthew White Ridley was appointed Home Secretary, he was also in charge of prisons, the Metropolitan Police and other police services, the regulation of aliens, naturalisation, public housing, burial grounds, infant and child care, lunacy and mental health, mining, relations with local government, health and safety, factory inspections, workmen’s compensation, the use of human bodies in medical training, friendly societies, registration of trades unions and the control of explosives. Yvette Cooper might want to ponder that when she feels the burdens of her portfolio.

Between 1894 and 1936, the Home Secretary was also required to be present at royal births, to ensure that the babies were genuine members of the royal family and the line of succession. The first to do so was H.H. Asquith, who attended the birth of Prince Edward of York (later Edward VIII) at White Lodge in Richmond Park on 23 June 1894. The practice was discontinued after 1936, but the last baby born with the Home Secretary in attendance as part of his duties is still alive: Sir John Simon attended the birth of Princess Alexandra of Kent (now Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy) at 3 Belgrave Square on Christmas Day 1936.

When Princess Alexandra was born, she was sixth in line to the throne, Edward VIII having abdicated a fortnight before, after The Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II); The Princess Margaret; Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester; her father Prince George, Duke of Kent; and her elder brother Prince Edward of Kent (now the Duke of Kent). Today Princess Alexandra is 57th in the line of succession.

It is sometimes impossible to predict what foreign news stories will resonate with the public in Britain, but the abduction of 276 pupils from the Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok in north-eastern Nigeria on 14/15 April 2014 caught the attention. The girls were snatched by Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram, who are well practised at kidnapping, but there was something about the scale of the outrage and the age of the victims which was especially shocking. It is sobering to remember that 92 of the girls kidnapped more than 10 years ago, exactly a third, remain unaccounted for, presumably still in captivity or worse.

It would be the 301st birthday today (if mortality were not a thing) of Frances Brooke (née Moore), a novelist, essayist, playwright and translator who was born in Lincolnshire, the daughter of a clergyman, and emigrated to Canada at the age of 40. She moved to Quebec to join her husband, the Rev Dr John Brooke, who was chaplain to the British garrison, and in 1769 published her second novel, the epistolary romance The History of Emily Montague. Well received by contemporary critics, it features extensive descriptions of life in British America and relations between the British and French settlers and colonialists and the Huron and Iroquois populations. It is regarded as the first novel to be written in Canada.

“For me, cinema is a vice. I love it intimately.” (Fritz Lang)

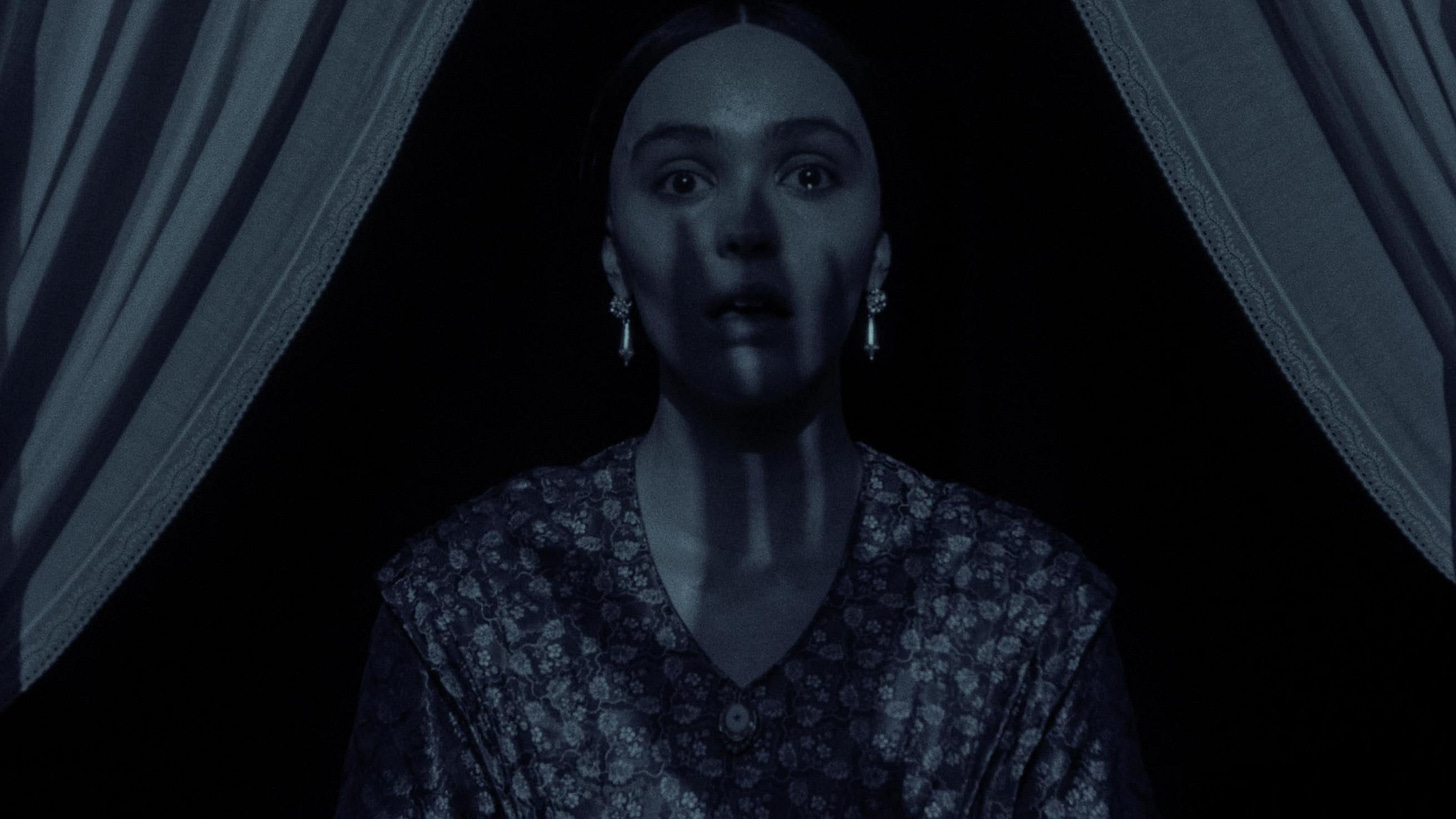

“Nosferatu”: I was wary of Robert Eggers’s remake of the pioneering 1922 Expressionist masterpiece Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens. It is a film which goes beyond the iconic, as I recently explained in CulturAll, and to attempt a new interpretation is fraught with danger. At a very basic level, what’s the point? But my brother-in-law was keen to see it, and my sister had made it unmistakeably clear that this was an experience up for which she was not, so I happily accompanied him out of sheer curiosity. I hold my hands up: I think Eggers has made a very good film. The cinematography is gorgeous and meticulous, there are superb performances from Lily-Rose Depp as Ellen Hutter, Bill Skarsgård as Count Orlok, Ralph Ineson as Dr Sievers and Simon McBurney as a horrifying Herr Knock, while Willem Defoe positively feasts on the scenery as Professor Albin Eberhart von Franz. I found Nicholas Hoult slightly blank and formless as Thomas Hutter but that is easy to overlook. It is a punishing 132 minutes, eerie, gruesome, overhung by death and disaster, and there is no happy ending. But in its dark, corrupted horror there is a spirit that I think F.W. Murnau, who directed the original film, and perhaps Bram Stoker, whose Dracula it so unashamedly plagiarised, would have found satisfyingly chilling.

“Nightmare: The Birth of Horror: Dracula”: since we’re on the subject of vampires, this episode from the excellent 1996/97 BBC documentary on the origins of the genre of horror was first shown just before Christmas 1996. It’s fronted by the wonderful Sir Christopher Frayling, and was a companion to his book of the same name; I remember reading it as I rounded out my teens and realising, almost incidentally, that I was without any great intention in the field of what is broadly considered cultural history, and found it gripping. Frayling is a hugely engaging presenter and shows real relish in his work, and the evolution of vampire mythology is (I think) fascinating and revealing of the world around it. Nearly 30 years on there’s less in here that’s revelatory but a very enjoyable 50 minutes in the safest of hands.

“7/7: The London Bombings”: when I remind myself that the Islamist terror attacks on public transport in London happened nearly 20 years ago it seems at first a shockingly and unexpectedly long time, but on reflection the world in which we lived then was so profoundly different: barely any social media (Facebook was still student-only), the BlackBerry in its pomp, Tony Blair having recently won a record third election victory for the Labour Party and, on 6 July 2005, it was announced that London had won the competition to host the 2012 Summer Olympics. Then it all changed. This thorough and well produced documentary has an impressive roster of talking heads: Blair himself, Baroness Manningham-Buller, then Director-General of MI5, the Metropolitan Police’s counter-terrorism chief Andy Hayman, newly elected Labour MP for Dewsbury Shahid Malik (the ringleader, Mohammad Sidique Khan, was from his constituency), but most of all some of the survivors, who talk bravely and frankly about the horror of the day. It’s a sombre and often harrowing tale, but for me, having brushed against parts of that world subsequently, one of the encouraging conclusions was the necessarily uncelebrated scale of success that MI5 has achieved in stopping so many similar atrocities. The number of late-stage terrorist plots foiled in the past 20 years is comfortably into triple figures. But the threat level is currently at “substantial”, meaning an attack is “likely”, and has been at that level or higher since the events of 7 July 2005. It is, to use that hoary phrase, the new normal.

“The Best of… Not Only… But Also”: this week marked the 30th anniversary of the death of Peter Cook, the influential writer, satirist and comedian, who suffered a gastrointestinal haemorrhage after years of heavy drinking and reached the end of his road aged just 57. The BBC marked the occasion with a few pieces from their archives, including a “best of…” compilation from Cook’s famous partnership with Dudley Moore in Not Only… But Also, a comedy sketch series which ran for 24 episodes between 1965 and 1970. There are some moments of unadulterated and blissful comedy gold, but, so many decades on, I have to conclude that Not Only… But Also was probably more important as a catalyst and an influence than as comedy in its own right. Bluntly, much of it has not aged well, and seems excessively self-regarding, stiffly stagey or simply dulled by the passage of time. That is somehow reflective of Cook himself, I suspect. A strange, flippant, oddly flirtatious and restless man when not in character, he was fundamentally unhappy in his own skin and easily bored. He has been dubbed “the father of modern satire”, and his legacy is visible in Monty Python, Adrian Edmondson and Rik Mayall, Fry and Laurie, Have I Got News For You?, Brass Eye, Eddie Izzard and others. Yet, with the stand-out exception of Private Eye, which he bought and effectively saved from an infant death in 1962, Cook’s personal achievements can look slender. He was instinctively, imaginatively, brilliantly funny, and perhaps that is enough.

“The Revenge of Middle America”: Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook turn the attention of their podcast behemoth The Rest Is History to the pivotal US presidential election of 1968 and the return from the political wilderness of former vice-president and failed California gubernatorial candidate Richard Milhous Nixon. When we think about 1968, we think, of course, of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, of the shock decision by the exhausted President Lyndon Johnson not to seek a second full term, of the violent and ill-omened Democratic National Convention in Chicago, of the devastating Tet Offensive by the Viet Cong and the Vietnam People’s Army, of the My Lai massacre and of anti-war student protests across America. It can too easily frame that November’s election purely in terms of the Democratic losers and make it seem a foregone conclusion, but Vice-President Hubert Humphrey trailed Nixon by only half a million votes nationwide in the end. It is vital to understand the role of Nixon himself though, that most complex, convoluted and contradictory of presidents. He had lost the presidency to John F. Kennedy in 1960 by not much more than 100,000 votes, many of them probably fraudulent, and after an unsuccessful bid to be Governor of California, his home state, in 1962, he had quit the political stage, bitter, resentful and disappointed. Many contemporaries thought it would be the last page of his public career, even though he was only 49, and he sat out the Democratic landslide of 1964. By 1968, however, he was never seriously challenged for the Republican nomination and took the White House with a powerful hold over his party. Tom and Dominic explain how and why.

“Let me live, love, and say it well in good sentences.” (Sylvia Plath)

“Sir Keir Starmer can combat Elon Musk with cold hard facts”: I’ve long had a great deal of time for Fraser Nelson, who was a brilliant editor of The Spectator for 15 years, transforming the magazine’s commercial status and profile, and for me it’s always worth reading his work. He has recently joined The Times as a columnist—I should say “rejoined”, because he began his career there writing first about business then Scottish politics—and this column in his new guise is a helpful and sober-minded intervention in the current storm over child sexual abuse, grooming and the influence of Elon Musk. He argues that the debate should focus on solid, reliable, relevant data, which is available in abundance, but which may cause partisans on all sides to address problems which make them uncomfortable. As Fraser concludes, “the truth, awkward or not, is the best tool of defence”.

“Britain needs babies! And PM should find the right words to say so”: I confess that this article in The Times by political correspondent and columnist Lara Spirit made me somewhat uneasy. I don’t dispute that the United Kingdom has a falling birthrate, and that this presents real and difficult demographic challenges like a shrinking population and a consequently smaller tax base, and potential costs and difficulties in caring for the elderly and treating their inevitable health needs. But the very notion of “natalism”, encouraging more women to have more children, is to me one of the murkiest of policy areas. I have sympathy with and see the intellectual case for ensuring that the costs of having and rearing children are not prohibitively high and, in Lara’s words, “helping women who would like to have children fulfil their wish to do so”. We should certainly design our taxation and benefits system so that it does not deter parenthood. I am, however, anxious of essentially permissive policies giving way to anything even slightly prescriptive. I don’t have children nor do I plan to have, but many, perhaps most, people do. Finding that finest of lines is an extraordinarily sensitive matter, and there is always the unsettling image of loyal Nazi women being awarded the Mutterkreuz, the Cross of Honour of the German Mother, which was bestowed on German women who had four or five children (bronze), six or seven children (silver) or eight or more offspring (gold). Nevertheless, I think this is a sober and measured exploration of a real problem, even if I can’t immediately suggest any especially effective solutions. Worth reading.

“The Wire, but make it Keeley Hawes”: from the entertaining Substack The Metropolitan, “a weekly newsletter about the pop-cultural and social experience of British Generation X” (what’s not to like?), Rowan Davies uses an illness-facilitated second viewing of the BBC police drama Line of Duty to think more deeply about it. While she acknowledges the futility of a straight comparison, she argues that Jed Mercurio intended his creation as a kind of analogue of David Simon’s The Wire, a sprawling, multi-character, morally ambiguous state-of-the-nation epic. Davies touches on interesting parallels like George Eliot’s Middlemarch and the novels of Dickens, and presents a thoughtful, plausible analysis. At this point, I will have to admit that I have only ever seen a couple of episodes of The Wire, and none at all of Line of Duty. So regard that as a caveat.

“Blood, incest, giant phalluses! The cheat’s guide to Greek tragedy”: again in The Times, Patrick Kidd takes recent productions/adaptations of Sophicles’s Oedipus the King by Robert Icke and Ella Hickson and Brie Larson’s forthcoming British stage debut in Elektra as a starting point for a brisk, lively bluffer’s guide to Greek tragedy. This caught my eye as I saw the Icke production last November and found it staggeringly good; Mark Strong was predictably fine but huge credit to Lesley Manville’s understudy as Jocasta, Celia Nelson, and the insanely brilliant June Watson, undimmed at 89, as Merope. In addition, my book club has just finished reading Madeline Miller’s impressive The Song of Achilles, so I’ve been in an ancient Greek frame of mind recently. You may be familiar with much or all of what Kidd says, and he makes no apology for it being a “cheat’s guide”, but it is also a useful reminder, as debate is rekindled over the value of studying classics, of just how foundational to our culture the surviving Greek tragedies are and how elemental and acutely observed they remain. (I made my own case two years ago here.) Violent, gruesome, vicious, heartbreaking and ineffably human: we owe Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides a vast debt, as we do Greek and Roman literature more broadly.

“Does Kemi Badenoch have a plan?”: whether it’s deliberate, I don’t know, but Simon Heffer can sometimes come across as much more bufferish and blustering than he is. He is enormously learned and perceptive: his doorstop biography of Enoch Powell, Like the Roman, is a brilliant and meticulous study, he has written rich and thoughtful accounts of Britain before the First World War, during the war and between the world wars, and his editing of the diaries of “Chips” Channon has been exemplary. In The Spectator, he examines Kemi Badenoch’s leadership of the Conservative Party at this early stage—remember she has been in office for 10 weeks—and while you may not agree with his assessment, it is careful and well argued. I regard Nigel Farage with more unease and distance, perhaps, than Heffer does, but I sense that I share a degree of optimism (tempered by experience) about the possible future of the party. By a long chalk one of the most plausible assessments I’ve read recently.

Always give your best…

… as the 37th President of the United States said on leaving the White House; never get discouraged, never be petty; always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.

Like Richard Nixon, I hope you will all not be away for too long. À bientot.

Wonderful and some intriguing links. Thank you.