Strengthening America's hand in the Pacific

The Pentagon is upgrading its presence in Japan to strengthen its challenge to China, but there may be a degree of reinforcing the alliance before a Trump presidency

Human instinct draws us to flamboyant, dramatic military leaders, like Douglas MacArthur, George Patton and William McRaven. The lesson of the last century, however, is that success in war rests as much on careful, painstaking bureaucracy and organisational efficiency (as Marshall and Eisenhower would have recognised). This makes analysis of defence policy more challenging, but it is important to see the importance of institutional change behind the scenes.

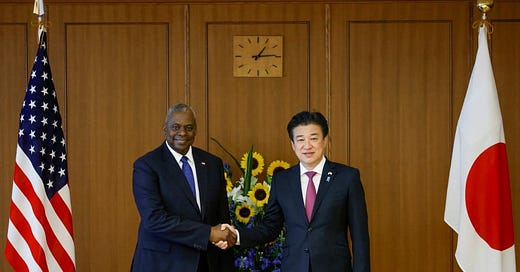

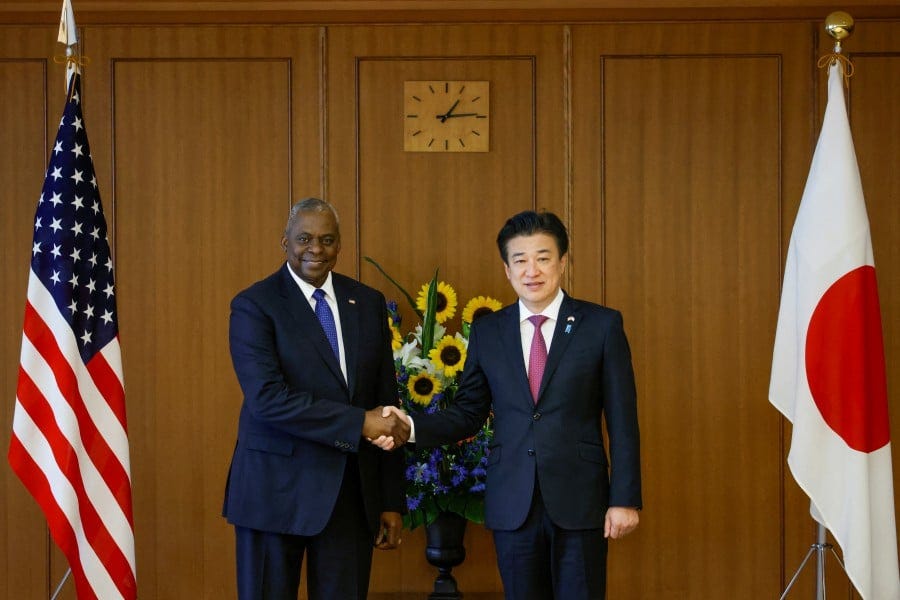

Last month Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III and Antony Blinken, Secretary of State, visited Tokyo for a so-called “two plus two” ministerial summit with their Japanese counterparts. The main themes emphasised were defence co-operation, “extended deterrence” and regional security, with China on everyone’s mind if nobody’s lips. One announcement which slipped out discreetly but has enormous implications was the decision to upgrade United States Forces Japan, the organisation which manages the 50,000 American service personnel deployed in Japan, to a “joint force headquarters with expanded missions and operational responsibilities”.

It would be easy to pass over this as the kind of dry administrative rebranding so common to the armed forces, like when the Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief became the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1949, functionally the same role but with a new description. Secretary Austin’s announcement is more than that, though.

The current US Forces Japan is a subordinate unified command of US Indo-Pacific Command, the oldest and largest of the Pentagon’s 11 combatant commands, and while USFJ is headquartered at Yokota Air Base in Tokyo, INDOPACCOM is based 4,000 miles away at Camp H.M. Smith on Oahu in Hawaii. Moreover, USFJ has strictly limited responsibilities: it supervises bilateral military relations between the US and Japan, manages personnel and infrastructure issues and maintains the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement which has been in force since 1960.

The new joint force command will do more than that. It will have operational responsibility for American military units in Japan, allowing it to “assume primary responsibility for co-ordinating security activities in and around Japan in accordance with the US-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security”. While it will still be subordinate to INDOPACCOM, it will have a much greater level of autonomy, addressing concerns that communications between Japan and Hawaii in the event of a crisis could be subject to serious and damaging delays. Bluntly, if a military stand-off with China escalates, the US commander in Tokyo will be able to respond.

The transformation of US Forces Japan has to be seen in parallel with developments in the Japanese military. Last year the Ministry of Defence in Tokyo announced the establishment of a permanent joint headquarters which will have operational control of all three branches of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). When it becomes fully active in March 2025, it will be commanded by a four-star officer, the same rank as the chiefs of staff of each of the three services, and will be based in the Ministry of Defence building in Ichigaya, eastern Tokyo. The upgraded American command will be a direct counterpart to the new Japanese joint headquarters, allowing close and seamless co-operation.

The timing of this announcement is not coincidental. The United States has a complicated network of security relationships across the Indo-Pacific: as well as the co-operation and security treaty with Japan, the Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of Korea (1953) commits both parties to provide mutual assistance in the event of conflict and allows American military forces to be based in South Korea; the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979 provides for the United States to supply “such defense articles and defense services in such quantity” to Taiwan “to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability”; and the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement between the United States and the Philippines, agreed in 2014, allows US forces to be stationed in the Philippines for extended periods and commits to greater interoperability between the American military and the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

It is no secret that Donald Trump’s commitment to these alliances is hardly inked in blood. His view of Taiwan is coloured by his (inaccurate) belief that the island “did take about 100% of our chip business”, and his promise of the imposition of tariffs and a trade war with China if he is re-elected president would have serious economic repercussions for Japan and other regional players. The government in Seoul, meanwhile, is worried about Trump’s unpredictable but sometimes cordial relationship with the North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

The Biden administration rightly cannot bind its successor’s hands, should Trump be victorious at the ballot box in November. But it knows that Trump pays little attention to details and organisations, so Washington can entrench the current defence alliances in institutional terms to change the landscape Trump might inherit. It has already brought Taiwan more fully into the international community, agreed additional defense industrial co-operation with South Korea and pledged to work with the Philippines on cyber security. In addition, the NATO summit in Washington last month created a number of new frameworks to support Ukraine.

If Donald Trump becomes president again next year, the United States’s strategic posture will change significantly, though not necessarily in ways which can yet be predicted. The current administration cannot prevent that, nor should it be able to. What it can do, however, is make the status quo more difficult to dismantle. Japan has the potential to become America’s key ally in the Indo-Pacific, and the transformation of US Forces Japan is a significant step towards realising that.