State of the nation: Our Friends in the North

Peter Flannery's majestic 1990s television serial still stands like a giant in cultural history

I was 18 years old when Our Friends in the North first aired on BBC2 on 15 January 1996. It was very much my parents’ sort of television: my mother and my stepfather liked good, literate TV, and it was set just up the road in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (I grew up, as my vowels in no way give away, in Sunderland). I watched with passing interest, still just about being at an age when my mood swung from pretentiously worthy to dismissive of “serious” art. Part of me wanted to devour it, part of me was as happy with old episodes of The A-Team or The Fall Guy. (Don’t @ me, as the kids say.)

It has become a classic piece of British drama, highlighted last year—its 25th anniversary year—by the British Film Institute. Consequently, the BBC, having access to it in the vaults, have been screening it on BBC4 and BBC2, and this evening the former channel showed the last three episodes, set in 1984, 1987 and 1995. This is the heart of my childhood, and I have lapped it up anew with fierce hunger.

A word on identity. I have (according to www.ancestry.com) not a single drop of English blood in me, being mainly of Scots descent, as I’ve always known. Although I had my confusions as a child, since I matured (!), and especially after spending nine years in Scotland, mostly at the University of St Andrews, I have felt the ancestral blood course more powerfully. I have come to know Scotland much better, paradoxically as my few known relatives have died or faded from sight, and I think now of Scotland as the blood home, albeit not where I grew up. I “identify as” Scottish now, I wear tartan, and in the unlikely event that I have to pick a side at sporting fixtures, I pick Scotland over England (and England over Ireland or Northern Ireland, and Ireland over Wales).

Nevertheless, although I twitch at the skirl of the pipes and the smell of haggis, I grew up in England, and specifically in the North East. This was a matter of happenstance: when my parents left the outer rings of Glasgow (Motherwell and Wishaw) and sought a new life south of the border, their destination was determined by my father’s career. He was a psychologist, and was interviewed for two jobs. The first—which, fatefully, he got—was at Winterton Hospital in County Durham, so we moved to Sedgefield, a small market town not then yet known as the political base of Tony Blair. But it could have been very different.

The other job was in Wales. My father always used to talk about the “narrow escape” of Colwyn Bay, and I assume the job he didn’t get must have been at the North Wales Hospital, a psychiatric institution in Denbigh, 25 miles away. Had be been successful, by struggle for identity would have been between Scottish and Welsh, and North Walian at that. I might even have acquired some knowledge of the Welsh language, though Denbighshire is not a stronghold, Welsh was less widely spoken then and I have no great facility with spoken languages (though, probably because I have a good memory, I can learn written languages quite quickly, viz. my neglected French, Latin, German, Italian and, God help it, Greek).

Anyway, Sliding Doors moments aside, it was in County Durham that I emerged, a longed-for baby, first seeing the light in North Tees Hospital in Stockton-on-Tees. (I was ginger at birth, a cause of some alarm to my dark-haired mother and, perhaps, suspicion to my very dark-haired father.) It remained family lore, mostly but not wholly jokingly, that I was a changeling, or at least a spare child left over in a cupboard and palmed off on unsuspecting parents. Happily, anyone who knew my parents will tell you that, for better or worse, I was definitely theirs genetically, with my mother’s features and retentive memory and my father’s expressions, sense of humour and intonation. Sorry, both. But literally your fault.

This is a diversion but it has a purpose. I spent the first 16 years of my life in the North East, moving from Sedgefield to Sunderland (for prep school) in 1981, and I didn’t leave until my abortive three terms at Oxford where I wrestled with Greek and finally had to admit defeat. In 1996, I upped sticks to St Andrews, fell in love with it (and some important people in my life, many of them still features) and have never lived for significant stretches in the North East since except when ill.

I do not sound like a North Easterner. I would never have been a Geordie, as I have to correct people (they are from Newcastle) but I have nothing of the Mackem voice about me either. When I started working at the House of Commons, I had to work hard to persuade a senior clerk about to retire, Frank Cranmer, that I was indeed from Sunderland: he had been born there and educated at Bede Grammar School for Boys, as it then was. It was the alma mater of David Stewart of the Eurythmics, Sir Tom Cowie, the transport tycoon, and Derek Foster, long-time MP for Bishop Auckland and Labour chief whip. Frank has a gentle but distinct Mackem accent, lovely to listen to; and my sister, although she has been in London for a decade, is still unmistakeably from Sunderland. I am, well, not so much.

For all that—I can manage some phrases in decent Mackem but am not fluent—I was heavily marked by the North East. Prep school in Sunderland (not awash with independent schools even then) and then the larger pond of Newcastle Royal Grammar School, to which I owe a huge amount, gave me a degree of local pride, but it was inculcated in me away from the classroom too. The 1980s and early 1990s, when I was growing up, were hard ones for the North East, as the traditional industries of coal-mining and shipbuilding declined and then disappeared. I won’t get into a debate here about the influence and legacy of Thatcherism, but I saw an old way of life vanish. I went on a school trip to see the last Sunderland-built ship launched; it was the Superflex Kilo, built in Pallion and launched at the end of 1988. Ships are still repaired on the Wear but no longer built from scratch. And that was a momentous legacy which came to an end. In the middle of the 19th century, a third of the UK’s ships came from Sunderland, and it was matched only by Glasgow (also ancestral lands for me) for the volume of shipping constructed.

Coal, too, was a powerful master. It had been mined since the 14th century, and the Northumberland and Durham Coalfield was huge, employing at its height 250,000 men and producing 56 million tons of coal from 400 pits. That was about a quarter of the UK’s supply of black gold, and it involved some extraordinary feats of engineering and sheer human endurance. There were mines stretching out eight miles under the North Sea, and, although the writing was on the wall after the industrial strife of the mid-1980s, the last pit in the North East, Ellington, closed in 1995. It was a shattering blow.

Perhaps even more than shipbuilding, mining defined the North East. Miners were, after all, the aristocracy of labour, providing a whole industrial ecosystem, a strong sense of professional pride and generational employment. (Richard Burton, born to a mining family in the South Wales fields, spoke fascinatingly and movingly of the industry and its place in society when interviewed by Dick Cavett in the 1970s.) It was from the mining communities that sprang the Charlton brothers who bestrode football in the 1960s and 1970s, and indeed their father Bob didn’t see the 1966 World Cup final in which they played until he had returned to the surface after his shift in the pit. The family also included Jack, Jim, George, Stan and Jackie Milburn. These were hard, tough, stoic men, and it showed in their careers away from the mines.

It marked the landscape in all sorts of ways. I hope she won’t mind me saying this, but I remember we were visited by the now-famous and always-exceptional journalist Rachel Cooke (there was a family link which is too boring to explain) in the early or mid-1990s and, while driving around County Durham, she asked what a strange tower topped by a wheel was. I was nonplussed: the headstock wheels on mines or former mines were as familiar to me as hills and rivers, but she had not seen one before. (I hope I remember that right and don’t do her an injustice.)

This long autobiographical detour is to explain the extent to which I felt anchored in the North East when I first saw Our Friends in the North. This was why it struck a chord deeper than simply well-written and superbly acted drama. I heard it described recently as the only TV drama about social housing policy, and, in some ways, it is. But it is also the tale of the development and decline of Tyneside in all its rich and tragic detail. I love Newcastle, and have none of the rivalry between it and Sunderland that the football engenders. Ma, a latecomer to football but characteristically giving it her all, worked up disdain and sometimes real vitriol for at least Newcastle United "(“Fucking Mags, dirty bastards”) if not the city itself; for all of us, the city of Newcastle was our cultural, educational and social pole star, with its excellent university (later joined by Northumbria), its museums and galleries, its medical infrastructure which Ma came to know well over the years and especially as she faced up to the rare cancer which shared the distinction (with Covid-19) of killing her.

Although Newcastle was paradoxically smaller than Sunderland (a spread-out town not yet in possession of city status, which came in 1992, it was the ancient settlement on the Tyne which was the “real” city. We went there or to nearby Durham at weekends (though many North Easterners, über-provincial and suspicious of distance, would not do so). It was where we caught trains or planes. It was the recognisable skyline with its 12th century castle and cluster of bridges (the famous arched Tyne Bridge looks like the Wear Bridge but is larger).

Our Friends in the North (yes, we’re still talking about that) begins in 1964, and the election of the Labour government under Harold Wilson after 13 years of Conservative rule. We meet the influential and charismatic leader of Newcastle City Council, Austin Donohue (brilliantly played by Alun Armstrong), who has transformed his city but now craves a bigger stage. Tipped for office in the new government but denied, he sets his sights on further wealth and power though public relations and lobbying.

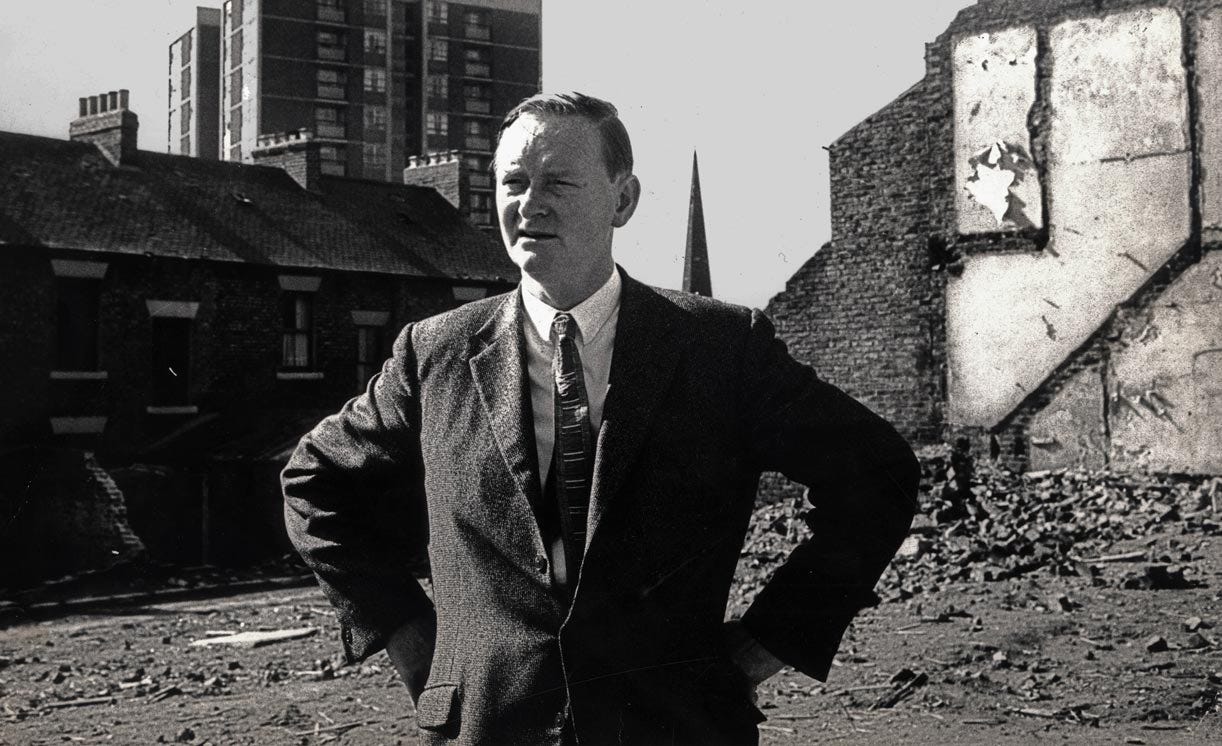

This was intimately familiar to people of a certain age in the North East. Donohue is a very thinly veiled portrait of T. Dan Smith, who led the council from 1959 to 1964 and controlled its planning department to transform the city’s ageing centre, clearing old and crumbling houses, building tower blocks and beginning work on the huge Eldon Square shopping centre. Smith was a visionary. His chief planning officer wanted Newcastle to become “the Brasilia of the North”, a reference which would find fewer echoes now, and much did change, often for the better. But many of the 1960s design projects have not aged well. One construction, the Brutalist Trinity Square car park, grabbed the limelight in the savagely magnificent Get Carter, a film which, as well as being a crime masterpiece, is a fascinating snapshot of Tyneside in the throes of transformation: Bryan Mosley’s character, local gangster Cliff Brumby, is memorably thrown to his death by Michael Caine’s Jack Carter from the car park. It was demolished in 2010.

Smith would have been a mildly famous ambitious city boss rather in the American mould if he had not also been found to be extensively and grandly corrupt. He worked closely with an architect called John Poulson, and Smith’s ostentatious lifestyle—he drove a Jaguar with the number plate DAN 68—was founded on illicit payments and bribes to grease the wheels of modernisation. For a while he rode high. The government appointed him chairman of the Northern Economic Planning Council, he sat on the Buchanan Commission on traffic management and was a member of the famous Redcliffe-Maud Commission which proposed comprehensive reorganisation of English local government. He was king of the quangocrats, disappointed by a failure to join Wilson’s administration but influential and well-remunerated.

Smith came unstuck in 1972. The palimpsest of Peter Flannery’s drama saw this played out in episodes two, three and four. In reality, the architect Poulson went bust, and the shockwaves reached and unseated Smith and the Conservative home secretary Reginald Maudling (Julian Fellowes’s Claude Seabrook in the television drama), who had been involved with Poulson’s business interests, was forced to resign, a catastrophic loss of a lazy but heavyweight politician from the creaking Heath government.

(Maudling would return to the Tory front bench as Thatcher’s shadow foreign secretary in 1975 but was out of sympathy, desperately tired and worn down by alcoholism; he died in 1979 at the age of 61. It was a sad end for a brilliant man; when he was dismissed, he reflected ruefully that he had been “hired by Winston Churchill, fired by Margaret Thatcher.)

If the initial episodes of Our Friends in the North encapsulate the wranglings of council politics in the North East, the series finds an even more iconic setting in the miners’ strike of 1984 in episode 4. I was too young to find the strike comprehensible at the time, but as I grew up and matured politically, it revealed itself to me as an absolutely crucial part of the Thatcher revolution, and I felt a degree of understanding of it because I knew the landscape and the communities in which much of the drama had played out. By the late 1980s, towns like Easington, Stanley, Murton and Houghton were shells of their former selves, unemployment sky-high, opportunities few, families devastated. Ma knew these places much better. She taught children excluded from school for “challenging behaviour” (I cannot now recall what the modish phraseology is and it changed throughout her career), and some of her pupils came from these hollowed-out places.

I will write at greater length about my mother. She died more than two years ago—we were alone at the end in her hospice room, as she went from sleep to the eternal rest of nothingness—and I am not afraid to say I adored her with every fibre of my being. We were exceptionally close, though neither of us regarded the other uncritically and the intimacy did not always show. Ma was very good at self-deprecation as she aged, but she was a brilliant woman, an imaginative author and natural anti-authoritarian who somehow found instinctive connections with “bad” children, seeing as if my magic what they needed to flourish and understanding what would and wouldn’t help them to survive, perhaps even prosper. She had no sentimentality, was brutally clear-eyed and realistic and said (I tend to believe her) that she didn’t much like children, but she cared deeply about her pupils and did everything within her power to give horribly damaged and disadvantaged youngsters the best tools she could to survive life. We joked that her funeral would see the criminal elite of Sunderland and County Durham, come to pay grateful respects; in the end, thanks to the pandemic-inspired lockdown, there was no funeral. But, my God, some of those kids loved her.

Back to the main road of this meandering journey. The depiction of the strike in Our Friends in the North is not impartial, and leans heavily towards the miners’ point of view. That is fine: drama can be partial and polemic. Although my perspective is different, there is no doubt that the strike was a tragedy for mining areas and the police were guilty of widespread brutality and violence, and, while I understand how she came to see it the way she did, Thatcher did not help by describing the miners and the NUM, balefully and wickedly led by the grotesque demagogue Arthur Scargill, as “the enemy within”. That hurt those who had provided the UK’s prosperity, dug out of hard and pitiless conditions. The miners were badly, criminally led: that their proud, tough way of life disappeared was, I will freely say, a tragedy, but by 1984 it was an unavoidable one.

I am a Conservative, and share a lot of Thatcherism’s ideological tenets (though I maintain she was the implement of a philosophy others had developed, from Hayek and Friedman through Powell and Joseph). Unquestionably, though, the Iron Lady was divisive, probably unnecessarily so. And I think the Miners’ Strike was a crisis in the genuine sense of the word, a turning point after which the political landscape of the UK would never be the same. Employers were set against workers, the government against the trades unions, the police against civilians. It caused enormous hardship and suffering, and the government, though its resolution was absolutely necessary if Thatcher was to avoid Heath’s ignominious fate, too easily forgot that we are one nation, a patchwork of communities and economic enterprises and lifestyles, intricately interwoven. The tearing-apart of that social fabric marks us still. Perhaps it always will.

The last two episodes of Our Friends in the North take the drama to (then) the modern day, covering 1987 and 1995. It is framed against the apparently unstoppable rise of the Conservative Party: Thatcher’s third election victory in 1987 caused the Labour Party and the wider movement existential doubts, despite Neil Kinnock’s brave work to modernise and root out those who were addicted to factional conflict rather than electoral persuasion. His speech at the 1985 Labour conference in which he took on the Militant movement is now rightly regarded as a classic piece of platform oratory; it was a raw, emotional, passionate baring of the Welshman’s soul in which he showed how much it mattered to him that Labour had access to power rather than just the best of intentions.

For the North East, which had been home to so much of the birth of the Labour movement, the late 1980s and early 1990s were painful. There was economic rival in some places; the huge Nissan factory in Sunderland began production in 1986, and has been a lifeline for the region (though it swallowed up the site of the aviation museum which I had adored as a child - they had an Avro Vulcan (XL319), for goodness’s sake, and you could climb into the cockpit!). But we remained a part of the country marked by unemployment, poor prospects, poverty and social ills. We became known for “twoccing”, the stealing for joyriding of cars (the word derives from the police phrase “Taking without the owner’s consent”), and many of Ma’s pupils went on to find careers of a sort in that activity.

(An absurd, tragic true cameo which encapsulates Ma’s teaching career: she once looked over a pupil’s shoulder to see him scrutinising a map of our area of Sunderland with various “nickable” cars carefully marked on it. Spotting a Ford Sierra XR4i drawn by my father’s house—he and my stepmother lived a few streets away from us—she leaned over and told the pupil that he had sold his car and it was therefore no longer there. I think the young man amended the map appropriately.)

Our Friends in the North reflects this fragile state brilliantly. Gina McKee’s Mary Soulsby becomes a Newcastle MP with a whiff of emerging New Labour about her, and her ex-husband Tosker (Mark Strong), having lost a fortune in the 1987 crash, opens a club which promises renewed success. Nicky Hutchinson, Christopher Eccleston’s anchor of the whole series, has found success and eminence as a photographer. But childhood friend Geordie Peacock (Daniel Craig) has been a homeless alcoholic and is out of prison on parole, a life of crisis and disaster which gradually begins to rally.

As the series concludes, there is a sense of hope. Nicky and Mary, after a stormy romance, begin their relationship anew: “Tomorrow’s too late,” he tells her after chasing down her car. “Why not today?” The iconic ending sees Geordie walking across the Tyne Bridge as Don’t Look Back In Anger, Oasis’s anthemic consideration of regret and dealing with the past, blasts out. It had been released only weeks before and caught the mood perfectly. Every time I watch that final scene, as I did just before I started writing this, I weep. I can’t help it. It brings the whole story arc together, throws a metaphorical arm around the characters’ shoulders and promises that perhaps everything can, in the end, be well. I do hope it was for them all.

This (overlong) essay has wandered, and will only make sense if you have seen Our Friends in the North. I make no (few) apologies for that. What I wanted to capture is the way the series encapsulates the social and political history of the North East, why it is so moving and why a sense of belonging to the North East, as I have, makes it so powerful. There are of course many other brilliant things about the drama. It is an ensemble cast of which directors and writers could dream—Christopher Eccleston, Mark Strong, Gina McKee, Daniel Craig, Peter Vaughan, Alun Armstrong, David Bradley, Malcolm McDowell, the underrated Tony Haygarth—and each is on exceptional form.

Eccleston and Strong disliked each other during filming, but their performances are outstanding. The period scenes are immaculate. For me, Gina McKee is the stand-out, the quiet, tough, long-suffering, brave and moral lynchpin of the interwoven cast, who goes from a young woman chafing at the prejudices which limit her to a successful and able Member of Parliament, finally seeing personal happiness. McKee is the only North Easterner in the main cast, born in Peterlee and growing up in Easington and Sunderland, and I have always carried a fierce torch for her. She is a consummate actress, as performance after performance has proved, from Croupier through Notting Hill to In The Loop, and I am reduced to speechless awe not just by her acting chops but her gorgeous lyrical North Eastern accent and statue-like looks. I’ll stop there: suffice to say I absolutely love her.

Our Friends in the North is absolutely a state of the nation drama. It takes in Britain from the 1960s to the 1990s, and using the focus of Newcastle and the North East, shines a light on some critical events and developments. It is superb TV drama, from Flannery’s screenplay to brilliant direction from (among others) Simon Cellan Jones. You can watch it in so many ways: an acting masterclass, an impeccable script, a piercing resonance with social history and the story of the working classes. From whatever perspective, it deserves every plaudit. If, by chance, you have not seen it, for God’s sake clear your diary and make good that deficit.

I have gone on too long, about too many thing (not least myself). Regular readers will know by parenthetic tendencies and determination to explain every last detail. I hope it might have been interesting, and it has made me realise I need to write another half-dozen essays, not least an appreciation of Ma, for those who didn’t know her or have only heard my inadequate, offhand characterisation. If you know the North East, this will mean more and I hope some of my friends from the North might see it and find something to strike a chord or two (yes, that’s you, Charles). Anyway, drama meets my life (not for the first time), and I hope the interaction makes some sense.