Ruler of the King's navee: a Royal Marine as First Sea Lord?

Rumours suggest General Sir Gwyn Jenkins RM will be the next head of the Royal Navy; it would be unprecedented, but are there any problems?

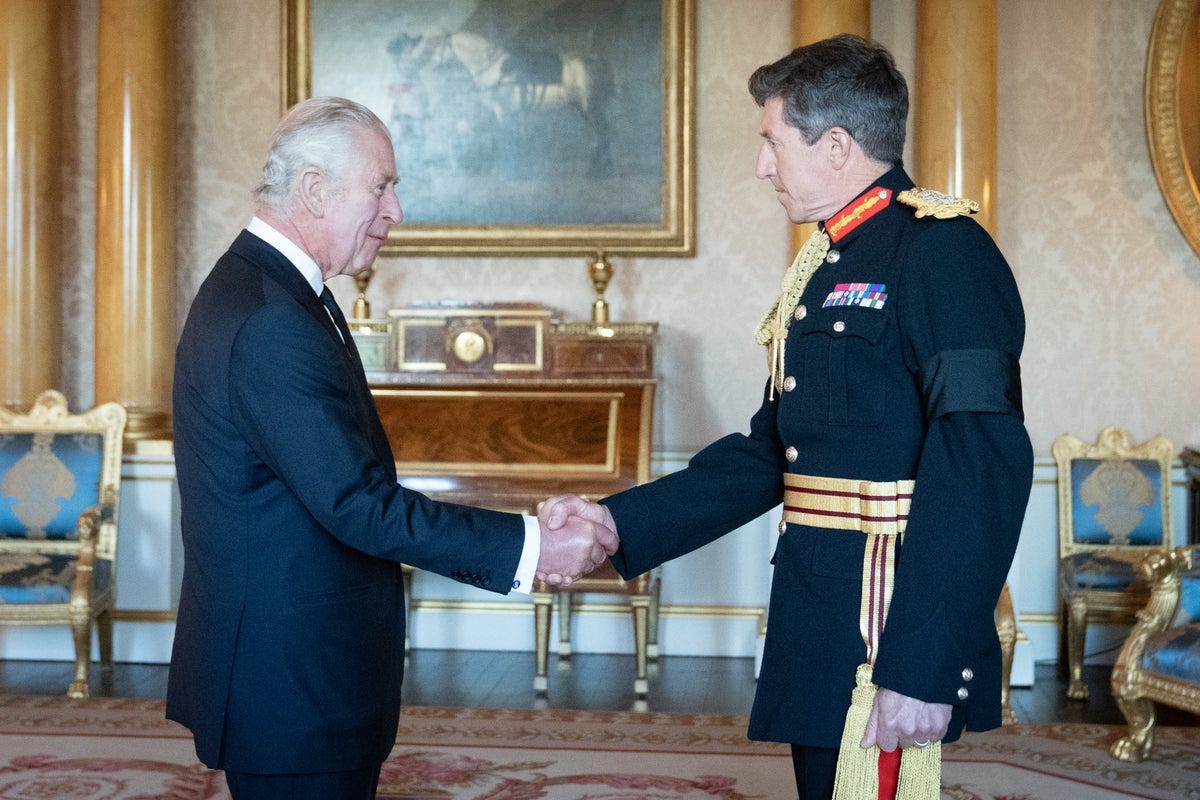

At the beginning of last week, The Sun reported that General Sir Gwyn Jenkins, former Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff and tapped by Rishi Sunak to be National Security Adviser only for Sir Keir Starmer to cancel his appointment, is being lined for a new role. Subject to approval from the King, Jenkins will succeed Admiral Sir Ben Key as First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff later this year.

The headline in this story is, of course, a Royal Marines officer being chosen to head the Royal Navy. The Marines are “the Royal Navy’s amphibious infantry”, one of its five fighting arms alongside the Surface Fleet, the Submarine Service, the Fleet Air Arm and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary, but they have always existed slightly apart from the navy too. They were formed as the Duke of York and Albany’s Maritime Regiment of Foot in October 1664, when James, Duke of York and Albany, later King James II and VII was Lord High Admiral of England. In April 1755 they were reorganised by Order in Council as His Majesty’s Marine Forces, controlled by the Admiralty and based at Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth. As well as acting as infantry on land, the Marines would engage with the crews of enemy ships during naval battles, and also maintained and enforced discipline on Royal Navy ships.

As a small and specialised division of the Royal Navy, however, the Royal Marines offered limited prospects for its officers. Until 1771, the highest they could rise was lieutenant colonel, the most senior positions being occupied by naval officers; that year, commandants were appointed for each of the three divisions at Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth at the rank of colonel. From 1812 these roles were upgraded to be held by major-generals or occasionally lieutenant generals, and in 1825 an additional role, Colonel Commandant and Deputy Adjutant General of Marines resident in London, was created, at the ranks of major-general, lieutenant general or general. In 1914 that post was renamed as Adjutant General and usually held by a full general, changing again to Commandant General in 1943. From 1977, the occupant was a lieutenant general, then a major-general after 1996. In 2021, having previously held the post from 2016 to 2018, Rob Magowan was reappointed Commandant General, but he had been promoted to lieutenant general in the interim.

Jenkins was appointed Commandant General in concurrence with Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff in November 2022, but he was already at the rank of general because of the first position, which has been held by a four-star officer since 1978. Indeed, since the downgrading of the post of Commandant General to a three-star appointment in 1977, becoming VCDS was the only way a Royal Marines officer could become a full general: the only officer to do so before Jenkins was General Sir Gordon Messenger, Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff 2016-19.

The point of all of this is that there are very few senior roles available to Royal Marines officers, and for a century there has not been more than one four-star general in active service at a time. From time to time Marines have held positions on the Admiralty Board like Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (although the Commandant General also usually attends), as well as tri-service roles like Deputy Chief of the Defence Staff (as opposed to Vice-Chief, as above) or senior jobs at Strategic Command (formerly Joint Forces Command). But the idea of a Royal Marines officer assuming the most senior position in the Royal Navy, as First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, is a striking proposition unprecedented in reality.

Unprecedented in reality, but not utterly unanticipated: in April 2021, at the Supersession of the Commandant General, as Major-General Matt Holmes handed the post on to Lieutenant General Rob Magowan, the then-First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Tony Radakin gave a speech in which he alluded to the possibility of a Marine heading the whole service.

How can it be that Marines—21 per cent of the Navy—have such successful joint and Defence careers and yet the most senior Navy roles elude them? Is it a lack of talent? No. It is cultural—on both sides… It is not acceptable that you can only get to 3* or 4* by “leaving” the Navy and relying on Defence positions.

It should be noted that this problem does not face the American military establishment, in which the United States Marine Corps is a separate service alongside the Navy, Army and Air Force; two USMC officers, General Peter Pace (2005-07) and General Joseph Dunford (2015-19), have served as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and two, Pace (2001-05) and General James E. Cartwright (2007-11), have been Vice-Chairman. The Commandant of the Marine Corps is a member of the Joint Chiefs.

Radakin, now Chief of the Defence Staff, was correct when he identified culture as the principal obstacle. This notion of Royal Marines officers being separate and sidelined is not one which has just appeared unexpectedly on the horizon. In 1902, Admiral Sir John Fisher, newly appointed Second Sea Lord in charge of personnel, devised a scheme to bring together the executive and engineering branches of the Royal Navy, with a single system of entry and initial training followed by later specialisation. All cadets would enter the service together at 12 or 13, spending two years at the Royal Naval College, Osborne, before proceeding to the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. They would train under a common curriculum and régime until reaching the rank of sub-lieutenant, at which point they would be assigned to the executive or engineering branches.

Initially, the Royal Marines were included in the so-called Fisher-Selborne Scheme, named after the Second Sea Lord and the Earl of Selborne, First Lord of the Admiralty (the minister in charge of the Royal Navy). However, it did not seem to encourage entrants to choose a career in the Royal Marines, and a separate entry scheme was restored in 1912. But Fisher explicitly addressed the point Radakin made 120 years later when he said of officers who went through his scheme:

In the rank of sub-lieutenant and junior lieutenant, they would be trained according to their specialisations but from the rank of commander onwards there would be much interchangeability of functions and all would have a chance of promotion to the highest ranks.

The question is certainly more urgent now that the Royal Marines constitute a fifth of the strength of the Royal Navy rather than eight or nine per cent 50 years ago. This is not a feature of the growth of the Royal Marines, but rather their shrinkage at a slower rate than the Navy as a whole, but in terms of balance the effect is the same.

This kind of unofficial discrimination, for want of a better word, is not restricted to the Royal Navy. The current Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Knighton, was appointed in June 2023 to become the first head of the RAF in its 105-year existence who was neither a military pilot nor aircrew-qualified at all; he had been an engineer—with a first-class degree from Clare College, Cambridge, it should be noted—and had led on major design and procurement programmes like the Future Combat Air System.

In the British Army, the issue is not much less acute: of the 43 Chiefs of the General Staff or Imperial General Staff since the position was created in 1904, all but two have been drawn from the traditional combat arms, predominantly (27 candidates) from the infantry; the remaining pair, Field Marshal Sir William Nicholson (1908-09) and General Sir Peter Wall (2010-14), had both been commissioned into the Royal Engineers.

Is this purely cultural inertia, tradition and snobbery? Yes and no. All of those factors play a part, certainly, and the UK armed forces are acutely traditional institutions from top to bottom. This can be positively beneficial, rituals and customs playing a critical part in forming a common identity and esprit de corps. But the argument that something should not happen because it has never happened before is, on its own, self-evidently absurd and would prevent all innovation and progress.

Of course there have to be some requirements in terms of experience as well as capabilities. (I am drawing gratefully here on an essay for the Wavell Room by Commander Oliver De Silva.) Every First Sea Lord since Admiral Sir Edward Ashmore (1974-77) has at least at some point previously held one of two positions, Second Sea Lord (responsible for personnel and naval shore establishments) or Fleet Commander (responsible for the operation, resourcing and training of ships, submarines and aircraft; previously Commander-in-Chief Fleet). Although both are now three-star vice-admiral roles, the Second Sea Lord was until 2005 generally a full admiral, and Commander-in-Chief Fleet was a full admiral, the job downgraded to vice-admiral when it was renamed Fleet Commander). They have been drawn from the ranks of Warfare Officers, and have therefore served in key roles on warships; all have been captains of ships at the rank of commander or above, even those who were initially in aviation.

Obviously enough, no Royal Marines officer has commanded a warship in the same way, though some have been given responsibility for shore establishments; for example, Brigadier Mark Noble was Commanding Officer of RNAS Yeovilton from 2009 to 2011, and the current Commander of HM Naval Base Devonport is Brigadier Mike Tanner. On the other hand, one could counter that no First Sea Lord has ever undergone the All Arms Commando Course and earned the right to wear a green beret, or commanded one of the battalion-sized Royal Marines Commando units like 40 Commando or 45 Commando. These latter positions are in general the same seniority as commanding a warship, that is, commander or lieutenant colonel (NATO OF-4). The question is how vital one regards captaining a warship—traditionally, it is true enough, the “core task” of the Royal Navy—in terms of qualification for overall leadership.

In terms of applicable experience of high command and staff jobs, it is not clear that this “ship of the line” requirement is justifiable. If General Sir Gwyn Jenkins does become First Sea Lord, he will bring a career which includes not only two years as Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, a hugely important role at the heart of senior leadership of the armed forces, but also experience overseeing global operations at the Permanent Joint Headquarters, and as Commanding Officer of 3 Commando Brigade, Deputy National Security Adviser for Conflict, Stability and Defence and Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (Policy). It is a wide and formidable range of experience.

The First Sea Lord is not a fighting admiral. He is responsible to the Secretary of State for Defence for the readiness and efficiency of the Royal Navy and acts as the principal military adviser on naval matters. He is also a member of the Defence Council and its sub-committee the Admiralty Board (which meets once a year), and of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, and he chairs the Navy Board which is responsible for the day-to-day management of the Royal Navy. Operational command of UK forces deployed overseas is generally exercised by the Chief of Joint Operations and the Permanent Joint Headquarters, part of Strategic Command. (The current First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Ben Key, was promoted from the role of Chief of Joint Operations.)

A great deal of the management, administration and policy advice which falls to the First Sea Lord, just as to the Chief of the General Staff and the Chief of the Air Staff, is effectively tri-service and depends on skills which are not specific to the command of relatively small units or vessels at an operational level. On that basis, there is no reason why a Royal Marines officer could not carry out the role perfectly well with the right service record and, again on that basis, it is hard to argue that Jenkins is in any way lacking.

There remains, however, a nebulous but unavoidable issue of credibility: what must a service chief, whether First Sea Lord or any other, have done for the broad mass of that service to have faith in him as their most senior officer? Does it include, in the Royal Navy, having commanded a warship? Commander de Silva, who has written with diligence on this, suggests not, pointing out that two of the last five Commanders of the Royal Netherlands Navy have been former Commandants of the Royal Netherlands Marine Corps.

On the other hand, in the United States—where, as I said, the Marine Corps is a separate service—of the 24 Chiefs of Naval Operations since the Second World War, although six have been naval aviators, all but one have commanded a warship at some point (and Admiral Jay Johnson, CNO 1996-2000, was commander of a carrier group for nearly two years). All but two heads of the Royal Australian Navy in the same period have captained a ship, the remaining two having commanded air stations, as have all the chiefs of the Royal Canadian Navy.

That is not to say that other countries are always right and that the UK would get it wrong to act differently. Almost certainly, there would be a proportion of naval personnel who were uneasy at the prospect of a Royal Marine as First Sea Lord (although those to whom I’ve spoken, especially those who know and have worked with Jenkins are entirely relaxed about his candidacy), but that is inevitable for any innovation. The deeper question is whether, firstly, command of a warship is intrinsic to being head of the Royal Navy, and, secondly, whether that is a sustainable viewpoint when one in five serving personnel in the Royal Navy is a Royal Marine.

It seems hard to maintain the idea that service as a Warfare Officer, which, while an important part of the Royal Navy’s capabilities, is only one of many specialisms, is a sine qua non for rising to the top of the service. The Royal Air Force has had a Chief of the Air Staff who was not trained as aircrew, and it does not seem to have presaged the end of the world. When Key retires as First Sea Lord later this year, there is only one other full admiral in active service, Admiral Sir Keith Blount, Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe since 2023. Jenkins already outranks the 10 serving vice-admirals (of whom three were only appointed to three-star rank in the past 12 months). So it is not even as if a Royal Marine is leapfrogging traditional Royal Navy candidates. If the decision has, as reported, been made provisionally in favour of Jenkins, it will be an important and likely beneficial step. And may even cause fewer waves than we might expect.

Great piece!

Two points that come to mind, from experience of the inside:

1) Part of the domination of the Combat Arms at the highest level is due to their domination further down at Corps, Div, and Bde, and - especially recently - within the Special Forces. This in turn is partly due to culture, partly due to politics, and also partly due to the natural progression of different Army career structures (I could wax lyrical about this but I won't for time!). Also, being pedantic, but we have also had a handful of Artillerymen as CGS in the British Army; the Royal Artillery is considered Combat Support rather than a Combat Arm in modern doctrine.

2) It is highly noticeable to anyone who has worked in Joint roles how common Royal Marine officers are in these departments - I've worked under several as an Army officer - partly due to the lack of positions within the Cdo Bde and also, frankly, due to some clever footwork on the part of the Marines. Noting that the current push in the MOD is towards the 'Integrated Force', I wouldn't be surprised if General Gwyn's appointment is a nod to this priority. A commander with significant joint experience is more likely to play nicely with the other services than one who has spent almost his entire career with the boundaries of the Navy.