Reflections on politics of the week

Some issues which have been on the news agenda (or my mind) but don't have enough material for a full essay (or I haven't thought deeply enough yet)

As occasionally in the past, there have been some stories in the news and some thoughts which have flitted across the skid pan of my mind which have piqued my interest but aren’t quite meaty or significant enough for a full essay, or are subjects I need to think about more. But I didn’t want to let them go past entirely unremarked, so I’ve bundled them together just to put them on the record and leave a marker. They may or may not resonate with you, but it’s always worth raising a flag.

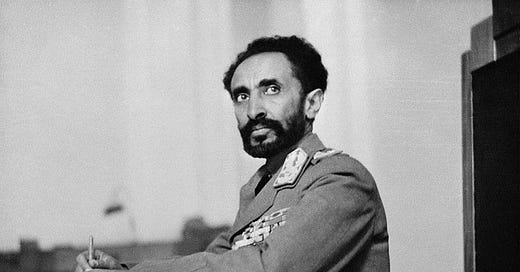

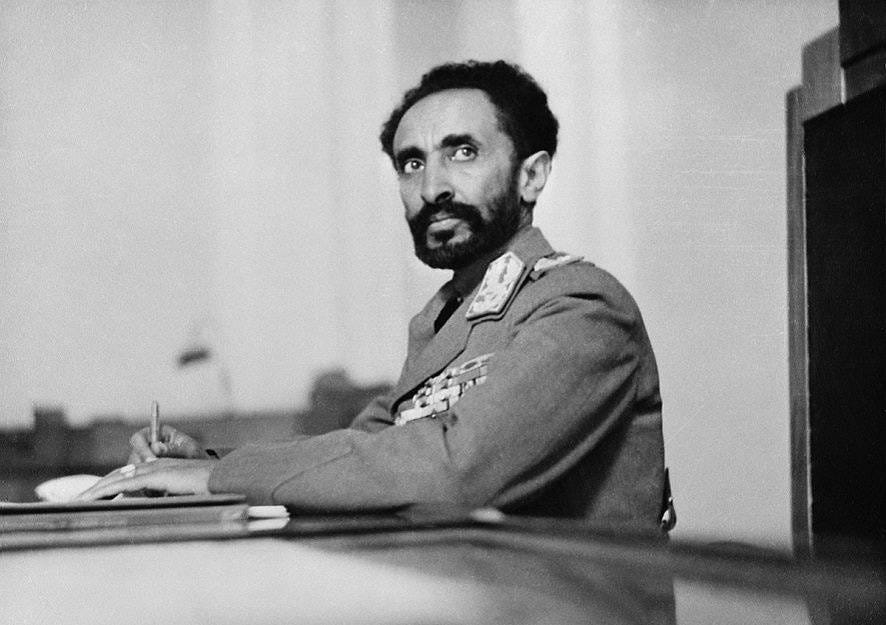

Calling time on the Lion of Judah

Today, 12 September, is the 50th anniversary of the deposition of the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie I. He was 82 and had been on the throne for 44 years, after 14 years as regent (Enderase) under Empress Zewditu. He was overthrown in a coup d’état by the Marxist-Leninist Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army, a Soviet-backed body made up of junior officers and enlisted men of the Imperial Army and known as the Derg.

Haile Selassie is a fascinating figure, hugely anachronistic by 1974. For followers of Rastafarianism, which had developed in Jamaica in the 1930s, he was in many ways literally the Messiah: some viewed him as the Second Coming of Christ and the incarnation of Jah, while others regarded him as a prophet. (His personal name was Tafari, and in 1917 was crowned Le’ul-Ras, becoming known as Ras Tafari.) From 1936 to 1941, following the Italian invasion and occupation of what was then known as Abyssinia, Selassie was in exile, going first to Jerusalem but settling at Fairfield House near Bath. He returned to Addis Ababa on 5 May 1941 after the Italian armed forces were defeated by British and Commonwealth soldiers under Lieutenant General Sir Alan Cunningham.

The emperor’s full title was “By the Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Elect of God”. “Haile Selassie” translates from Ge’ez as “The Power of the Trinity”, but he was also known to his subjects as Janhoy (“His Majesty”), Talaqu Meri (“Great Leader”) and Abba Tekel (“Father of Tekel”, his horse name which, according to Ethiopian tradition describes a ruler as “father of” his war horse). To Rastafarians, he was also known as Jah, Jah Jah, Jah Rastafari and HIM (for “His Imperial Majesty”). He was kept under house arrest after the coup at the Jubilee Palace in Addis Ababa, and on 28 August 1975 state media announced that he had died the previous day of respiratory failure. It transpired in 1994 that he had been murdered on the orders of the Derg.

The Ethiopian monarchy was enormously old. The Solomonic dynasty to which Selassie belonged had ruled since 1270 but claimed descent literally from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba through their son, the legendary Menelik I. But the polity could trace its lineage back to the Axumite Empire which had been established around the end of the 1st century AD. Importantly, Ethiopia is a Christian nation; Ezana, king of Axum from around AD 320 to AD 360 was converted to Christianity by his tutor Frumentius, a Phoenician former slave whom he appointed first bishop of Axum and head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church which still represents just under half of the population. Ethiopia was the only region of Africa to resist the spread of Islam, and its church maintains unbroken traditions since the earliest days of the faith. At 81 books, its biblical canon is the largest of any mainstream Christian denomination, its liturgy is celebrated in Ge’ez (although Haile Selassie sponsored translations of the Ge’ez scriptures into Amharic) and it claims that its Church of Our Lady, Mary of Zion, at Axum contains the Ark of the Covenant. (Yes, the actual ark.)

I mention this for a number of reasons. Partly it is because for people of my generation, the first association of the name “Ethiopia” is undoubted with “famine”. If you have never seen or have forgotten Michael Buerk’s mesmerisingly harrowing BBC report from Korem in northern Ethiopia in October 1984, watch it now. It is a masterpiece of foreign reporting: calm, almost quiet, controlled and devastating, and it was watching Buerk’s item that motivated Bob Geldof to organise first Band Aid then Live Aid to raise money for famine relief. The Derg was overthrown in 1991, and in 1993 Eritrea, the northern region of Ethiopia, became independent, but the two countries fought a costly border war between 1998 and 2000 and the dispute was not formally settled until 2018. Ethiopia remains plagued by civil unrest, however, and famine has become a feature of life again in some areas.

The government of Ethiopia remains authoritarian, and freedom and human rights have deteriorated since 2010, although the current prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, who has been in office since 2018, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his contribution to resolving the border conflict with Eritrea. But Ethiopia is an important country: with a population of 110 million, it is the 14th largest country in the world, and in the first two decades of this century its GDP per capita grew enormously (though at 159th in the world it remains very low, at just $4,019).

It also touches on one of my more niche interests, the cause of independence for Somaliland (about which I wrote for The Hill earlier this year) and therefore the geopolitical situation in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia has been landlocked since Eritrea became independent and until 1997 it had an agreement to use the Red Sea ports of Assab and Massawa, but it now relies on neighbouring Djibouti. This becomes complicated because Djibouti is home to Doraleh Multipurpose Port, part of which is controlled by the People’s Republic of China and houses a base for the Chinese navy, and Doraleh Container Terminal (now Société de Gestion du Terminal a Conteneur de Doraleh), which was built by Dubai shipping giant DP World but seized by the government of Djibouti in 2018 (though legal action is ongoing). DP World also operates a major facility at Berbera, Somaliland’s main sea port. At the beginning of this year, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a memorandum of understanding by which Somaliland will lease an area of coastal territory to Ethiopia to grant access to the Red Sea in return for a political alliance which could lead to formal recognition of Somaliland’s independence.

I also mention it because many years ago—while on holiday in Jerusalem, I think—I read Graham Hancock’s The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant (1992), in which he explores and largely endorses the Ethiopian Church’s claim to possess the Ark of the Covenant. The book was not reviewed well, and was the beginning of Hancock’s trajectory towards full-blown conspiracy theorist, and there are certainly flaws in it and some claims which are palpably absurd. That said, I found it had aspects which I found at least plausible, if not persuasive. Is the ark really in Axum? Did it ever exist? I don’t know. All I will say is that, having read Hancock’s book, I won’t say with certainty that it isn’t.

Hindsight changes your perspective

In connection with the elections for select committee chairs, I was thinking about parliamentary intakes, as eight new MPs stood for the positions, of whom only one, Patricia Ferguson as chair of the Scottish Affairs Committee, was successful (and was running against another newcomer, Gregor Poynton, so one of them had to win). Six new MPs have been given ministerial posts straight away: the Hon Georgia Gould, the Hon Hamish Falconer, Alistair Carns, Dr Miatta Fahnbulleh, Kirsty McNeill and Sarah Sackman (amusingly, two of them are the children of Labour peers). This has fluttered the dovecots of Westminster slightly, especially as some shadow ministers, most notably the shadow attorney general Emily Thornberry, were not given government posts.

All of the new appointments are able people and have every chance of thriving in ministerial office. But early promotion is not always a reliable guide of lasting success and posterity. I thought back the 2010 general election, my first as an official in the House of Commons as I joined just after the 2005 election, so the new intake from that year was the first I greeted as a body of men and women. Up to an including Theresa May forming her government in July 2016, 14 MPs elected for the first time in 2010 reached cabinet rank (or were ministers “also attending” cabinet), which is by most standards a swift rise: from newcomer to cabinet minister in six years is quicker progression than Winston Churchill (eight years), Clement Attlee (18 years), Margaret Thatcher (11 years) or Tony Blair (14 years).

How will the early stars of the Conservative Party’s class of 2010 be remembered? I leave you to judge. Here they are with the first cabinet jobs they held.

April 2014

Sajid Javid, culture, media and sport secretary

July 2014

Nicky Morgan, education secretary

Liz Truss, environment, food and rural affairs secretary

Attending cabinet

Matt Hancock, minister of state for business and enterprise & for energy

Esther McVey, minister of state for employment

May 2015

Amber Rudd, energy and climate change secretary

Attending cabinet

Robert Halfon, minister without portfolio

Priti Patel, minister of state for employment

Anna Soubry, minister of state for small business, industry and enterprise

March 2016

Alun Cairns, Welsh secretary

July 2016

Karen Bradley, culture, media and sport secretary

Andrea Leadsom, environment, food and rural affairs secretary

Attending cabinet

Ben Gummer, paymaster general

Gavin Williamson, government chief whip

Of those 14, only four are still MPs 14 years after they were first elected: one was promoted in office to the House of Lords, four stepped down voluntarily, four were defeated and one was deselected as a candidate. One became prime minister (albeit for 49 days), while five others were formal leadership candidates at some point. Five received knighthoods or damehoods (so far: Truss for the Garter?).

Other members of the 2010 intake who made slower career progress but might have more lasting impact in various ways include Rory Stewart, Louise Bagshawe (now Mensch), Penny Mordaunt, Nadhim Zahawi, Zac Goldsmith and, of course, Rehman Chishti.

Norwegian would

Jens Stoltenberg, the former Norwegian prime minister, finally steps down as secretary general of NATO at the end of the month, to be succeeded by ex-premier of the Netherlands Mark Rutte. He has served a full decade in Brussels, longer than anyone except Dutchman Joseph Luns (1971-84), though, in fairness, Stoltenberg was halfway out the door in 2021 and applied to be governor of Norges Bank, his home country’s central bank. He was appointed to the position on 4 February 2022 and was due to stand down from NATO that October, but 20 days later Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and it became clear that NATO would want to extend Stoltenberg’s term of office. In March 2022 he accepted a one-year extension, and in July 2023 the North Atlantic Council pushed his departure date back again to 1 October 2024.

Today Politico reported that Stoltenberg will become chairman of the Munich Security Conference, an annual summit on international security policy. He will succeed German former diplomat Dr Christoph Heusgen after the February 2025 edition of the conference, dubbed “Davos with guns”. It was founded in 1963 by Ewald-Heinrich von Kleist-Schmenzin, a former Wehrmacht officer who had been active in the July 1944 plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler then founded a publishing house after the war. Kleist retired in 1998 and was succeeded by Professor Dr Horst Teltschik, an academic and former official in the Federal Chancellery in Bonn and Berlin.