Politics exists for ideas, debated instead of imposed

Some think we are in a post-ideological era, or that political ideas are dogmatic, but politics existed to propose, test and implement doctrine

British politics is a tribal affair. We are more or less a two-party state—sometimes we can stretch to two-and-a-half but rarely for long—and we have been that way since political factions started to emerge not long after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the coronation of the Stuart heir Charles II. (By some calculations, including my own, he had of course been king of England, Scotland, Ireland and France de jure since his father’s head had hit the boards of the scaffold around 2.00 pm on 30 January 1649, and the Parliament of Scotland had declared him their sovereign on 5 February).

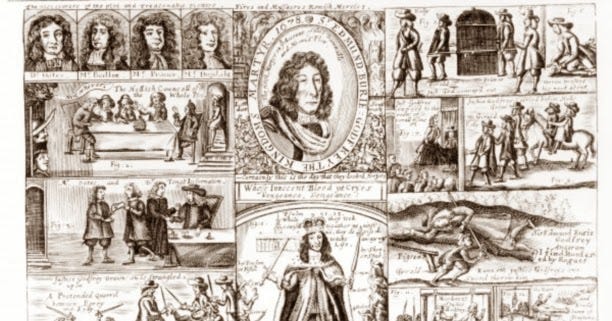

The first parties emerged during the Exclusion Crisis of 1679, when Protestant Members of Parliament grouped around the Earl of Shaftesbury introduced the Exclusion Bill to delete the king’s Catholic brother, James, Duke of York, from the succession. Charles saw that the bill might well pass the House of Commons, so exercised his powers under the royal prerogative and dissolved Parliament on 24 January 1679. Another Parliament was summoned the next day, another bill introduced and agreed to by the Commons, and another dissolution announced on 12 July. A third Parliament was then summoned on 24 July. Again the Commons agreed to an Exclusion Bill, and again the king dissolved Parliament at the beginning of 1681.

During this extended crisis of religio-political divisions, parliamentarians coalesced into two factions. Those who supported the Exclusion Bills became known as the Petitioners, because they petitioned the king to assemble the Parliament elected in the summer of 1679 (it would not meet till the following autumn). Those who supported the right of the Duke of York to succeed and wanted the Exclusion Bills defeated were dubbed Abhorrers because they presented addresses to Charles II abhorring the acts of the Petitioners. The temperature of the feelings provoked caused all kinds of insults to be thrown from each side against the other. Two of them stuck.

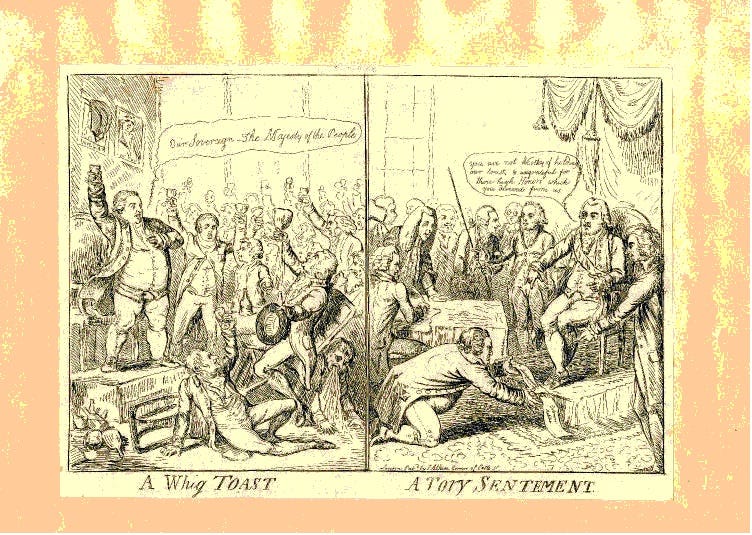

A whiggamore was originally a term of dialect from the north of England which referred to cattle drivers from the west of Scotland who came to Leith, the port of Edinburgh, to buy corn. They would shout in Gaelic “Chuig” or “Chuig an bothar”, “away” or “to the road”, which to Anglophone ears sounded like “whig” or “whiggamore” which became a derisive term for radical Presbyterian Scots during the Civil Wars. In the Exclusion Crisis it then became applied to the supporters of excluding the Catholic Duke of York. The “Whig” Party which developed was in favour of constitutional monarchy, the rights of Parliament and measures to prevent French-style absolutism, and became one of the two dominant parties until it merged with Radicals and Peelites in 1859 to form the new Liberal Party.

Another Scottish insult which crossed the border was the adoption of the Middle Irish word tóraidhe, an outlaw or robber. Anglicised as “Tory”, it was applied to the Abhorrers, and in October 1681, the anti-Exclusionist newspaper Heraclitus Ridens, one of the earliest political news-sheets, recorded the first appearance in print: “They [Whigs] call me scurvy names, Jesuit, Papish, Tory; and flap me over the mouth with their being the only True Protestants.” The Tory Party evolved to support a strong monarchy with effective prerogative powers as a counter-balance to the influence of Parliament and the established Church of England, often in its High Anglican variety, and drew its bedrock of support from the minor gentry. The party eventually transformed itself into the modern Conservative Party in 1834 when Sir Robert Peel, the Tory prime minister, issued his Tamworth Manifesto. Unlike “Whig”, “Tory” remains in popular and frequent use as a synonym for “Conservative”.

The two-party model essentially lasted until the turn of the 20th century. The exception was the Irish Parliamentary Party. This began in 1873 as the Home Rule League, supporting devolution of power to a new (or restored) parliament in Dublin, but was reorganised after the 1874 general election into a group of 46 MPs under Isaac Butt, the Member for Limerick. The Irish Party would remain a separate power bloc in the House of Commons until the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, though its strength collapsed in the December 1918 general election as the abstentionist Sinn Féin won most of the Irish seats.

The gradual extension of the franchise during the 19th century and the development of organised labour and trades unions brought a new radicalism to progressive politics in Britain. The Representation of the People Act 1884, otherwise known as the Third Reform Act, extended to the country seats the voting qualifications which prevailed in the borough seats, and almost doubled the electorate at a stroke, from around three million to 5.7 million. The interests of the urban working class were increasingly pressing but not strongly represented by the Liberal Party, so candidates began to come forward who were sponsored by the new trades unions. Local Liberal associations sometimes reached agreements with these candidates, and the first to stand for election was George Odger, a former shoemaker, who showed strongly in the Southwark by-election in February 1870.

A variety of socialist organisations was emerging, including the Independent Labour Party, the Fabian Society, the Social Democratic Federation and the Scottish Labour Party. Only the largely middle-class and intellectually inclined Fabians survive in 2023. The ILP fielded 28 candidates in the 1895 general election, but the fragmented nature of the socialist movement was clearly undermining any potential of significant parliamentary success. In 1899, therefore, the Doncaster branch of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants proposed that the Trade Union Congress convene a conference which would include all the various socialist and labour groups to allow them to form a single body to sponsor parliamentary candidates. That conference met at the Congregational Memorial Hall on Farringdon Street in London on 26/27 February 1900 and established the Labour Representation Committee as an umbrella body for socialist Members of Parliament with its own agreed policies and its own whips.

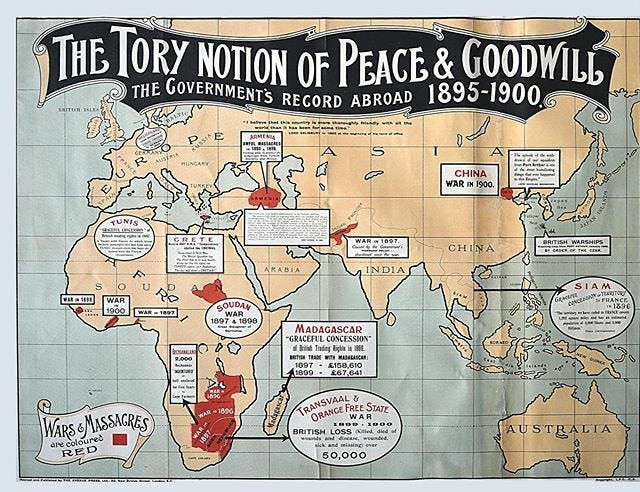

The performance of the LRC at the so-called “Khaki Election” in October 1900, as the Second Boer War was thought to be reaching a victorious conclusion, was disappointing. Only 15 candidates were fielded, of whom just two—Keir Hardie at Merthyr Tydfil and Richard Bell at Derby—won election. But it had been a landslide for the Conservatives and their Liberal Unionist coalition allies, collecting 402 of the 670 seats. (In 163 seats the governing parties had not even faced opposition.) It was the high water mark of Victorian Toryism, the last general election at which a major party would be led by a peer (the Marquess of Salisbury would retire in 1902) and the last before Victoria died. But it would all change so quickly.

The general election of January 1906 was a disaster for the Unionists and a triumph for the Liberals. But in fact it was the beginning of the end for the Liberal Party: although they won 397 seats, and even unseated the Unionist leader, A.J. Balfour, in Manchester East, they would never again win a parliamentary majority. Twenty-nine Members were returned under the banner of the Labour Representation Committee, and in less than 20 years the country would have its first socialist government. Simply, the Liberals had nowhere to go, no constituency to serve which would give them anything like the base for a majoritarian government. And so, by the time the party split between the followers of Lloyd George, who forced a coup and became prime minister at the end of 1916, and those who remained loyal to the man he displaced, H.H. Asquith, it had placed itself in the position which the third party has occupied ever since: passionately committed to electoral reform because a coalition of parties represent the only chance it has of ever occupying ministerial office again.

That the Liberal Democrats found themselves in a coalition government with the Conservatives from 2010 to 2015 does not disprove this fact. It was a freakish set of electoral results and the political imagination of the Conservative leader, David Cameron, which brought the coalition about, but those five years of responsible government has almost destroyed the party. In 2010, the Liberal Democrats won 62 seats in the House of Commons, enough to hold the balance of power. Five years later, having agreed to the introduction of higher student tuition fees and been defeated on a new electoral system and reform of the House of Lords, they were reduced to a mere eight MPs.

I dwell on this because our two-party system, sustained by our first past the post electoral arrangements, simply leave no room for a progressive centrist party to flourish. Especially since the 1970s, when the Conservative Party replaced Edward Heath with Margaret Thatcher and set in train a doctrinal revolution abandoning the post-war consensus and embracing monetarism and a wholehearted commitment to free markets, UK politics have been essentially binary: yes or no, left or right, statist or free enterprise. These polarities were comfortably represented by the Conservative and Labour parties, and there was neither space nor requirement for a third choice. Liberals were less statist than the Labour Party but more pro-European than the Conservatives; more willing to embrace the nostrums of the free market than Labour, but more communitarian than the Conservatives. They presented themselves successfully as the recipients of protest votes at by-elections and council elections, but when the voters were asked to make the important decision, the Liberal Democrats rarely seemed to represent a satisfactory solution.

The House of Commons can seem more ideologically pluralistic or nuanced than it is, because of the presence of distinct parties from the parts of the United Kingdom which have devolved assemblies and administrations: Scotland is currently represented by the Scottish National Party and the Alba Party, both committed to independence for Scotland; Wales adds Plaid Cymru, the nationalist organisation; while the tortuous politics of Northern Ireland send MPs from the Democratic Unionist Party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, the Alliance Party and Sinn Féin (though those last do not take their seats, as Sinn Féin is an abstentionist party). In addition, there is one representative of the Green Party of England and Wales, Dr Caroline Lucas (Brighton Pavilion). But this blossoming of small parties should not distract from the fact that the two traditional parties of government, the Conservatives and Labour, hold around 85 per cent of the seats in the Commons. As Benjamin Disraeli said in 1852, “England does not love coalitions”.

Now, let me be very clear at this point: I am satisfied with the current first past the post electoral system, and I do not think a change to a more proportional system, which would almost mandate coalition governments, would be a benefit to our polity. Of course the current system has its faults. It is designed to produce decisive results by amplifying electoral success, but that is inevitably a distortion while disenfranchises some voters. Of course it is not a flawless system. Nor, however, is a more proportional system delivering a multi-party legislature such as most of continental Europe has (and remember that our constitutional history and traditions are very different from theirs and, in our case, essentially evolutionary, with no complete caesuras. (Even our civil wars, which saw the temporary abolition of the monarchy, saw the House of Commons maintained as the principal representative body in England, and most of the old constitutional arrangements were re-established without much difficulty after 1660.) The coalition governments which a proportional system almost always creates means that there are compromises and deals between parties, with policies and commitments traded off against each other. This is all done after the election, and therefore beyond the control of the electorate. I think Liberal Democrat voters looking back on the 2010 Parliament should be seized of the disadvantanges which coalitions often bring.

Just to get a flavour of the alternative to our system, let’s look at the French Assemblée nationale, the lower house of their parliament. It consists of 577 députés, slightly smaller than the House of Commons but of a similar order. The Assemblée was last elected in June 2022, and the president of the Republic, Emmanuel Macron, is not supported by a majority in the legislature, though the centrist party which backs him, Ensemble, has by some way the largest group in the Assemblée, with 245 seats. After that, the recent left-wing alliance, the New Ecological and Social People’s Union (NUPES), is the next strongest party, at 131. The far-right National Rally has 89 députés, while the traditional right, the Union of the Right and Centre, has a mere 64. Then there are the camp followers: 21 députés of the miscellaneous left, 10 of the miscellaneous right and 10 regionalists, four broadly centrist députés and then one each from the Radical Party of the Left, the sovereignist right and an “other”. You can see straight away how difficult this makes both party management and the retention of clarity of purpose and adherence to comprehensive ideals.

Some people will point to the art of compromise and the horse-trading made necessary by coalition arrangements and say that these are good things, that they force people to cooperate more, find common ground, establish shared principles. That is one point of view. You could also say that it is a process of chasing the lowest common denominator, that trying to assemble alliances from such a fragmented legislature means dumbing down, adhering only to those policies which are most broadly supported and, might I suggest, most platitudinous. Think of those governments in the UK which have faced and faced down generational change. Would the Attlee government of 1945-51 have created the modern welfare state if it had been in coalition, smoothing out any rough edges and avoiding radicalism? Or would Margaret Thatcher have been able to transform the UK economy and Britain’s standing on the world stage after 1979 if she had merely led one partner in a coalition agreement? I think she would have argued that her Conservative Party was a broad enough coalition on its own, and that would remain true until at least the purge of the Wets in 1981.

Sir Tony Blair, one of the most electorally successful politicians of our age (certainly only Thatcher can match him), understood, and still understands, that politics is about ideas. At the time, I was very much not a Blairite. I have never been tempted to vote Labour, and in the 1990s, when Blair seemed unstoppable, I was a Conservative of probably a rather inflexible, exaggerated kind (teenagers are allowed to stray into overemphasis, I thin). I am still a Conservative: I think my Toryism has a tribal element, an extent to which it is in the marrow of my bones. In his later life, Enoch Powell explained his political convictions, and I think some of his remarks are worth noting.

I was born a Tory. Define: a Tory is a person who regards authority as immanent in institutions. I had always been, as far back as I could remember in my existence, a respecter of institutions, a respecter of monarchy, a respecter of the deposit of history, a respecter of everything in which authority was capable of being embodied, and that must surely be what the Conservative Party was about, the Conservative Party as the party of the maintenance of acknowledged prescriptive authority.

I can agree with much of that. Perhaps most of it. Certainly my friends will recognise traits like regarding authority as immanent in institutions and adhering to the maintenance of acknowledged prescriptive authority in me. I can, sometimes, be radical, but in the main I regard change as having a duty to prove its case. I have written of the important role of ritual. Anyone who has studied history will be familiar with the human tendency to change things for the sake of it, to regard change as a virtue in itself and the new as inherently superior to the old. That, surely, must be antithetical to Toryism.

I have mellowed since the mid-1990s, or else I have become wiser, more experienced, more imaginative and more curious. Part of that process has caused me to reassess Blair as a politician and leader, spurred on, I must confess, by a contrariness which wants to rehabilitate him all the more as the far-left use him as a shorthand for deceit, dishonour, disenchantment and devilry. Last year I wrote an essay about what I jocularly called “born-again Blairism”, and it is certainly true that when I see Sir Tony make a public appearance these days, the level to which he can effortlessly outperform our current crop of politicians is dramatic. Whatever you think of his ideas and his government, it is hard to deny that he was an exceptionally skilled communicator and campaigner.

Last year, the BBC screened a five-part documentary called Blair and Brown: The New Labour Revolution. It is a brilliant series with contributions from all the eyewitnesses and participants you could expect, and it brings the decades of New Labour to life vividly and accurately. While, as I say, I am not a Blairite, watching the BBC series brought home to me profoundly one or two observations about the phenomenon of New Labour. The first is that Blair instinctively, wholly and immediately “got it”, grasped what had been wrong with Labour’s proposition in the 1970s and 1980s and what had to be done to regain the electorate’s trust: essentially, the party had to reassure the voters that it supported their individual and familial desire to get on, to be successful, to have an agreeable life with creature comforts. Blair saw that with painful clarity. By contrast, in my opinion, Gordon Brown did not get it at all, or ever. He took the more conservative view that the Labour Party simply needed to present its high-tax, interventionist ideology in a more palatable and sophisticated way. I am not sure he ever thought there had to be fundamental change.

Another observation was the the true genius, the tutelary angel of New Labour and one of the most gifted politicians of the past 50 years is Peter Mandelson. Not only did he see the need for change as clearly as Blair, he knew how to achieve it, how to sway public opinion, and, in addition, he had the self-awareness and insight to see that he did not have the skills necessary to be the party’s saviour. He knew he was cast as Père Joseph, not Cardinal Richelieu. (The other towering talent of the Blair years, I think, was Alan Milburn, now lost to front-line politics; I may return to him more fully another time.)

Blair was right about ideas. They are the lifeblood of politics. In the 1990s we talked sometimes of being in a post-ideological world, but it was not true. We allowed ourselves to think, particularly when New Labour accepted a great deal of the Thatcherite revolution as a fait accompli, that our political masters had nothing now to do except compete over their efficiency of management, who would run the country more effectively. That was a dismal prospect, a reduction of politics to an exercise in bureaucracy and middle management, not even leadership. And it attempted to return the favour to Thatcher by portraying all that Blair did as inevitable, overwhelmingly obvious and impossible to contradict. Get enough sensible people together, was the implication of the era, and they will reach an agreed solution, which it is then our duty to implement. Ironically, Blair sometimes exemplified Thatcher’s old mantra of TINA: there is no alternative.

I think this was a misstep on Blair’s part. In the Labour manifesto for the 1997 general election, he said as follows:

New Labour is the political arm of none other than the British people as a whole. Our values are the same: the equal worth of all, with no one cast aside; fairness and justice within strong communities.

For me this was sinister and oppressive. If New Labour was so closely identified with the “British people as a whole” that you couldn’t see the join, then the inference was that to oppose New Labour was to oppose the people. TINA again. And this rejected Blair’s mantra that politics is about ideas. If you have ideas, you must expect others to have different, sometimes contradictory ones, and debate is how we reconcile these things. I present my view of the world, you present yours, and the people decide whose they like better. That, surely, is how a liberal democracy operates.

Blair is also wrong, though by no means unique in this respect, when he contrasts “ideas” with “ideology”, and condemns the latter as rigid, unyielding dogma which takes no account of reality. I don’t accept that. It’s not inherent in the meaning of the word, and I think of ideology simply as a more coherent, more rational collection of ideas. But Blair was right in one respect, without saying it: “ideology” is what people tend to call ideas with which they don’t agree. For him, New Labour had “ideas” and “values”, while the Conservative Party had “Thatcherite ideology”. Once you’ve seen it, it’s hard to unsee.

Politics is not management. It is not administration. It cannot always be a grand vision, but when you seek to make a contribution to the public world, you will, and must, have ideas behind you. Ideas can be big or small, and can be framed in a variety of ways. And what you regard as your principles must never become slavish idolatry. An example: as a mainstream, pro-armed forces Tory growing up, I took it as unremarkable and second nature that I supported the nuclear deterrent, first Polaris and then Trident. Of course we must have nuclear weapons: we want the United Kingdom to be a strong country, and a strong country must have the strongest possible weapons. I gave it little enough thought, if I’m honest, because no-one else did. People who opposed the deterrent were far-left lunatics, from Michael Foot through CND down to the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. Jeremy Corbyn was a unilateralist. It was the faith of the impractical, the idealistic, the unworldly.

Two years working for the House of Commons Defence Committee did not change my mind. The members of the committee were all avowed retentionists. They understood the sophisticated strategic arguments for retaining and indeed replacing the deterrent. Of course it was expensive, but what price our ultimate security? Not so long ago, though, I started to think about it. And, without rehearsing the arguments (because you can read them here if you’re interested), I realised that the line I’d always taken, the propositions I’d always accepted, made no sense to me. So, reluctantly, I decided that I didn’t believe the nuclear deterrent worked. It was a hard realisation but if you can’t accept you’ve been wrong, you’ve no business telling people your opinions.

My point, made in a manner which is perhaps less than succinct, is that politics is about difference, clash, argument—it’s much less about consensus and common ground, or at least about instinctive consensus. We talk about democracy, thinking it means “people power” (“demos” and “kratos”), but in a representative democracy it’s much more about the power to choose between competing visions of the world, difference collections of ideas. And if we don’t have those, if we reject the discussion of principles and philosophy, instead having our parties compete among each other to show or suggest who would simply be most competent at administration, who would most effectively manage the existing institutions of state, we cheat the electorate. We dismiss the notion of values or priorities and assume that everyone is the same in what they believe, and just want the received wisdom implemented well.

This is not only a denial of choice, it is a misrepresentation of the way the world works. It assumes that political problems can be reduced to a series of propositions to which, if you think hard enough and apply enough data, there is a single, rational, “right” answer. Surely not? you cry. Surely in an age which is ever more scientific, in which we have access to more information than ever before, in which we are better educated and have access to better analytical tools than ever before, we are creeping ever closer to a point at which we can solve problems? We can find the “correct” mechanism to control inflation, or maximise revenue from taxation while promoting economic growth, or design the most effective healthcare system.

It’s not true, and it’s not true because we don’t live in a rational world. We are human beings, and we interact with each other, and human beings are not machines but organisms, not subject solely to logic and equation but also to instinct and imagination. To believe that we can reach a stage where politics is just about competence is to commit a category error. It’s about the conception and development of ideas, the exposition of them and the persuasion of an audience to a vision of what the world can be like.

We shouldn’t be afraid of this conclusion. Think about your political heroes, the people who inspire you and whom you wish to emulate. Whatever part of the political spectrum you are on, it’s unlikely, I suggest, that they are predominantly leaders who were effective managers or competent administrators. Instead they will be great orators, or imaginative thinkers, or impressive writers, or persuasive and dynamic personalities. Try it. That’s no bad thing, because politics is a human business. Humans fight for ideas more easily and with more commitment than they do for spreadsheets.

It’s the beginning of a new calendar year, Parliament has returned from its periodic adjournment, the prime minister and the leader of the opposition have made speeches to try to create narratives for the next months, and we know that Parliament will be dissolved in December 2024 at the latest. So an election is in the offing. Let’s try to do better, be more articulate and philosophical, think more, and try to engage with ideas. Better that, I suggest, than simply crouching behind the parapet and waiting for the other side to self-destruct. It may not alter the final result, but we should at least feel rather better about ourselves and the world.