Please, sir, can I have some more?

Select committees always want more resources, but we should be careful to ensure that we maintain quality if we increase quantity

I come back again to select committees. You will, I hope, forgive my apparent obsession but they were the centre of my life for quite a few years, and, as a childhood politics nut, I immersed myself in the parliamentary ecosystem and thought a lot about how it operated and what were its shortcomings.

It is accepted wisdom that select committees have flowered since the Wright reforms of 2010, which enhanced the authority and mandate of committee chairs and sought to increase the visibility of the detailed scrutiny which select committees carry out. I broadly agree with that narrative. Good committees can explore issues of public policy (and, let us be fair, chase ambulances) in a way no other House of Commons body can, and, if properly arranged, with MPs thoroughly briefed and prepared, present a public spectacle which is edifying and educative as well as a boost to the profiles and egos of Members of Parliament.

When it works well, it can grapple with matters which have aroused genuine public interest and expose a great deal of information. In 2016, a joint body of the Work and Pensions and Business, Innovation and Skills committees examined Sir Philip Green over the sale of BHS and concerns over the viability of its pension fund. It was a tense and combative inquiry, as Sir Philip was reluctant to submit to the committees’ scrutiny and remained defiant over his stewardship of the high-street chain. He would later describe the MPs involved as a “complete bunch of old wankers”, but the inquiry had real impact: in 2017, he paid £363 million into the BHS pension fund and his umbrella organisation, Arcadia Group, went into administration in 2020.

We ought not to suppose that all high-profile committee work is so noble or so telling. For a gruelling and gruesome six months, I was second clerk of the Home Affairs Committee under the chairmanship of Keith Vaz, now out of Parliament and comprehensively disgraced (the Independent Expert Panel report on his conduct is worth reading, and was greeted by many House of Commons staff with a mixture of vindication and relief). As chair of the committee, to which he was not elected by the other members, as was the practice in those days, but nominated by an order of the whole House, he enjoyed the profile of leading one of the Commons’s busiest committees and one which covered a range of subjects which often touched a nerve with the public: crime, policing, public order, counter-terrorism.

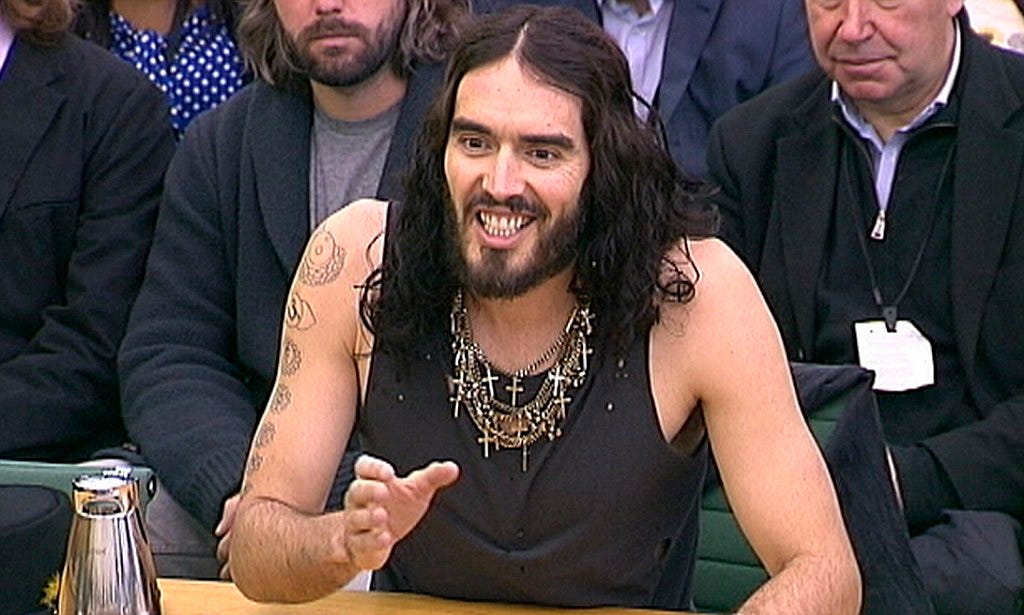

It was a commonplace that Vaz was peculiarly publicity-hungry, even for a Member of Parliament. He adored celebrity witnesses, so he managed to bring Russell Brand, Mitch Winehouse and then-mayor of London Boris Johnson in front of his starstruck colleagues (The Guardian’s Marina Hyde was withering of this tendency), and successive home secretaries were frequent flyers. All were good for copy. Nonetheless, although Vaz was—incredibly—chair for nine years, undone only by consorting with male prostitutes and offering them cocaine, it is difficult to point to many changes in public policy attributable to these media stunts.

Undoubtedly committee chairs became more famous in the period after 2010. Journalists and broadcasters realised as they had not done before what potential jewels of drama these hearings could be, and chairs like Margaret Hodge (PAC), Andrew Tyrie (Treasury) and John Whittingdale (Culture, Media and Sport) achieved a profile outside Parliament of which they could not previously have dreamed. That is by no means a wholly bad thing. The scrutiny work of select committees is detailed, extensive and sometimes influential, and captures the public mood much more easily than the chamber itself; and all politicians know that media profile is a very valuable currency, to be spent for good as well as ill.

Inevitably, however, with the greater public profile and the authority of election by the whole House, chairs have come to see their positions as magnified in importance. There have been some who have shown little enthusiasm for important-but-dull matters like departmental annual reports and accounts, preferring punchier and more immediate subjects which occupy the week’s headlines. With that new, elevated view of themselves, it was only a matter of time before they came to demand greater resources, both for themselves and their committees.

I will admit that such resources were not always lavish. When I joined the Health Committee in 2005, we had a secretariat of six—two clerks, two subject specialists and two administrative staff—and that was a representative headcount for most committees. It imposed certain limitations on the pace of work: there was a simple human limit to how often we could meet, how many inquiries we could conduct and in what depth. These limits, as it happens, were rarely reached before the more circumscribed limit of Member attention, since MPs on select committees have a dozen other claims on their time. Nonetheless, it suggested a simple equation: have more staff and do more work.

Many Members looked enviously at committees in the US Congress, and a lot of Commons committees would visit Washington regularly and swoon at their size and dignity. The current House Budget Committee, for example, has 36 members, with a chair and a formalised “ranking member” (congressional committees are organised on strict partisan lines) and the average headcount for a House committee is 68: this includes dedicated legal counsel, investigators and media advisers. It is, obviously, of a different order of magnitude from those in the House of Commons.

Committees in the Commons do have access to what we would call “specialist” advice. Some, like the Treasury Committee or the Environmental Audit Committee, have secondees from the National Audit Office, trained in financial analysis and value-for-money assessments. Committees now have named media officers (when I started we had a share of someone who worked with half a dozen other committees), and some, like Justice or the Joint Committee on Human Rights, have their own legal advisers.

In 2002, after recommendation from the Modernisation Committee, the House set up a Scrutiny Unit, headed by a middle-ranking but usually high-flying clerk. The unit has around 25 staff of varying specialisms, including lawyers, economists and statisticians, and was designed to provide “surge capacity” to committees on specific inquiries. As well as the departmental committees, the Scrutiny Unit also serves ad hoc committees on draft bills (the much-vaunted “pre-legislative scrutiny”) and performs other tasks which might otherwise remain in the interstices of the committee system.

Clearly, though, our committee system remains small compared to its American counterpart. And therein lies a siren call: give us more! With double the staff, think what a committee like Foreign Affairs or Work and Pensions could do! Think of the exacting scrutiny to which they could subject government policy and spending. After all, it is often argued (and rightly), committees are minnows set against the departments they are required to oversee. DCMS, a small Whitehall institution, has 3,000 civil servants, while the Home Office, across its various agencies and departments, musters a staff of 35,000. This is a daunting mismatch.

I do, however, with the realism or jaundice of more than five years out of the House, have reservations. One is presentational. The size of Westminster committees, usually around 11 at the moment, makes them manageable and of a human scale. The chair knows all the members, probably well, and can interact with every member of staff as required (though the clerk of the committee will usually control that relationship, more or less strictly). A modest agenda of one or two (maybe three) inquiries at a time allows the MPs to engage fully and actively with the committee’s work, though some subjects will interest them more than others.

Perhaps most importantly, the evidence sessions, the public heart of select committee work, are agile and can be directed. Even with a full complement of, say, 11 MPs around the horseshoe, each will be able to ask questions of the witnesses, can pursue lines of inquiry which arise from the evidence and can work together to advance the scrutiny at hand. Some chairs will dominate the public sessions, while others will sit back and let members have free rein, but in the two hours of an average evidence session, the examination of witnesses is a live, responsive, immediate thing. It can twist and turn to follow lines that may emerge, and it can dwell on a particular subject if information is not forthcoming or witnesses are clearly evasive.

Anyone who has watched a congressional committee will know that it is a much grander, stiffer and more stage-managed affair. Members often read out long prepared statements to preface their questions (a particular bugbear of mine) and putting those remarks on the record is often a major priority. Questions tended to be allotted by strict time limits, with a congressman having, say, five minutes to grill the witness, and there is little connection between each bout of inquiry, no sign showing of joined-up thinking by the committee as a whole.

This is inevitable. With dozens of committee staff, as well as their own substantial coteries, congressmen can exist in a solipsistic bubble. The massive resources at their disposal encourage self-importance, and each can be forgiven for seeing him or herself as the star of the show. That attitude, which smacks of grandstanding rather than scrutiny, would simply not wash in Westminster. A chair would pull back an excessively keen MP, or bring in others to allow a fairer distribution of questions. Likewise, even the most self-important and inflated chairs (no names, no pack drill) will find their members restive if the committee runs the risk of becoming a one-man show.

Here is the conundrum, the impossible balance in how committees work. Clearly, a small professional staff will know a chair and committee inside out, will understand their approach to issues and will have a strong insight into what they want to achieve. The MPs will find them responsive and supple, with well-attuned political antennae. There will be an implicit understanding that a high operational tempo will sometimes be needed to get the work done, but that such exceptional overwork is temporary and will bring rewards and compensations.

Undoubtedly, however, that small staff can only deliver a limited programme of scrutiny. If the agenda is too full, the committee will struggle to react to events and crises which arise suddenly, and the chair may have to make painful decisions about what to pursue and what to leave alone. That will sometimes require difficult and frank conversations between chair and clerk. MPs—partly, I would offer, because House staff are so good at delivering the near-impossible—have a tendency to think that a wish expressed is a wish that will come to pass. I certainly had to have some robust and (on my side, anyway) bruising exchanges with my chair on the Scottish Affairs Committee when his substantial ambitions ran up against the modest resources I had available. Of course the outcome was always a bugger’s muddle: he would concede some demands, we would agree to massage some tasks, and I would have to persuade the team to dig deep occasionally to deliver what was, if not impossible, certainly very challenging. I am sure every clerk has had similar interchanges.

The reverse is true of a much larger committee staff. The members will become more remote from the secretariat as a body, will not be able to know or recognise every member of staff, and the staff director (as clerk equivalents are called) will do a lot more people management and consequently less hands-on scrutiny. Each part of the committee machine will become slightly more self-contained and isolated, and the process will become more formalised, more constrained by procedure and less personalised.

But the reverse of my second proposition is also true. With a staff in the dozens, there will be no shortage of hands to draft papers, notes and reports, carry out rigorous and detailed research and manage a snowstorm of documents. This undoubtedly gives the committee more punch and a greater scope of scrutiny. But, I submit, something would have been lost.

Of course I should insert several caveats. The congressional system is not the only alternative to the status quo and there are lessons we could learn from European legislatures (though I fear the simple language barrier makes international relationships with non-Anglophone bodies rarer and more difficult). There are other models of scrutiny which can sit alongside rather than replace the way we do things now, like greater use of sub-committees or the appointment of rapporteurs (essentially individual committee members tasked with examining a particular area or issue).

This is perhaps tangential, but sub-committees are a double-edged sword. I clerked one during my fleeting stay on the Home Affairs Committee, examining the government’s counter-terrorism strategy, and they can work very differently from the main committee. They can be smaller, and therefore consist only of Members passionately interested in the subject, they can act more quickly with fewer moving parts, and they can, if there is Member endurance, expand scrutiny power out of proportion to the effort involved. But they can also act as policy ghettoes, with the members of the main committee essentially writing off a subject as something being covered elsewhere; although sub-committee reports must be agreed by the full committee before they become formal documents, so there is a backstop, in theory, against hobby-horses or bêtes noirs. Some clerks are (or were, anyway) very chary of them as bodies, and I saw more than one face fall when the idea would come up, but they are certainly a weapon which should remain active in the armoury.

There is no prospect of committee secretariats at Westminster ballooning to an American size. But it is the end of a spectrum. Moving along that spectrum will always appeal to MPs, and especially chairs, because Westminster is a world in which more = good. I would simply advise caution and careful thought by all interested parties: chairs, MPs, House staff, senior management and entrenched stakeholders in each committee’s purview. Stasis is a poison against which the Commons must always guard (though I have already argued that it is not as resistant to reform as people sometimes think), and it is right that the committee system should always seek to evolve and improve the breed.

But it does not—I hope—make me a heels-dug-in Bufton-Tufton when I say that change should be approached carefully and with great thought. Reformers must be alive to the danger of unforeseen consequences and I believe passionately that there is a thing we might call the “Westminster committee spirit” which has a lot to recommend it and can be lost, perhaps irredeemably. For ever cross-cutting committee which has sharpened the House’s cutting edge (like JCHR or Environmental Audit), there is a (perhaps predictable) disaster like English Votes for English Laws (EVEL), a complicated mechanism for voting on England-only legislation which was mourned by few when it was stripped from the Standing Orders last year.

More resources will undoubtedly allow committees to do more. But they are not a panacea. And we should be careful to distinguish between the quantity and quality of output. All I will say, in my occasionally mugwumpish, splitting-the difference way, is that change needs to be planned and “prevaluated”, and everyone seeking to change the House of Commons should be careful what they wish for.