Parliament engaging with the public can't be an empty gesture

The House of Commons has a popular e-petitions system, but it doesn't change policy: does it unreasonably inflate expectations and risk disappointing voters?

Petitions are great, aren’t they? In their original paper form, they were a stalwart tool and feature of the political landscape for a century, and when I was growing up there always seemed to be a limbless child or a blind person or somebody tending an animal, standing awkwardly by the famous black door of 10, Downing Street, while boiler-suited Royal Mail employees wheeled boxes and boxes full of paper into view. Its most effective manipulators were people like Mary Whitehouse, who established a “Clean Up TV” petition in 1964 which attracted half a million signatories; bizarrely to modern sensibilities, the proposed disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Wales prompted in 1912 a petition to retain the status quo which was signed by 2.3 million (roughly the same as the population of Wales itself but signatories were more evenly spread).

By the turn of the millennium, the idea of reams of paper covered with the names and addresses of individuals, all supporting a common objective (or opposing the same thing), seemed enormously cumbersome, not least physically, open to manipulation, and, from the point of view of the growing corpus of data protection law, a heavily planted minefield. Meanwhile, desktop computers were standard in office environments, and access to the internet was growing rapidly. If only a quarter of UK households had access in 2000, it was over half by 2002, three quarters by 2007. The transformative potential on establishing, signing and storing petitions electronically was obvious, and both government and parliament began to explore options in the early 2000s. In 2006, the Labour government unveiled an “e-petition” section on 10 Downing Street’s website, through which the administration could be pressed to act.

When I left the House of Commons in 2016, the new system of e-petitions was taking its first tentative steps in public. It was a well-intentioned response to a perceived demand for greater public engagement, but no-one at that time could be sure whether it would be effective or successful, nor exactly how it would work in everyday parliamentary life.

A report from the Procedure Committee in November 2014 had considered the idea of updating the House’s long-standing system of receiving petitions from ordinary voters. It looked favourably on the website then operated by the government and recommended a collaboration to use the existing architecture. In addition, there would be a committee of MPs to oversee the process (and take responsibility for the older, paper-based system), giving it not only the imprimatur of elected accountability but also a kind of moderating capability. The report used the sort of language which is always popular with Members, promising “a significant enhancement of the relationship between the petitioning public and their elected representatives” and noting with gleeful anticipation that the government’s system “had proved very popular with the public”. The proposals “can meet the needs of both the executive and the legislature—but more importantly, also of petitioners themselves”.

This language was a slam-dunk to find favour with a House still suffering PTSD from the expenses scandal, and a Petitions Committee was established after the 2015 general election, the undistinguished but often surprisingly quarrelsome Helen Jones (Lab, Warrington North) beating her amiable and laid-back colleague Nick Smith (Lab, Blaenau Gwent) by a serviceable margin. The committee began with five members of staff (small for a select committee but not tiny), a number which by 2022 had more or less doubled.

In its first days, the committee attracted a wide range of Members. The current deputy prime minister, Oliver Dowden, the departing and little-mourned former SNP Westminster leader, Ian Blackford, and one of the candidates for the Conservative mayoral nomination for London, Paul Scully, were early participants; so too were the single-minded and curmudgeonly Paul Flynn (who had a brief stint in Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet, becoming at 81 the oldest Member ever to serve in the opposition top team), Jim Dowd, a shrewd and clever Labour MP who could never quite take politics seriously enough to scale the uppermost heights, and Nick Hurd, son of former foreign secretary Douglas Hurd, an able and debonair man who rattled around junior ministerial office in the 2010s but left the House in 2019.

The process is straightforward. Going to the petitions homepage allows the would-be petitioner to see what petitions are currently open, search for those which apply to their area, and start a new petition. Each petition is open for six months, and if it attracts 10,000 signatures, the government will respond to the issue it raises. If a petition garners 100,000 signatures, the Petitions Committee will consider it for debate by MPs. There is also a useful help page which gives guidance on how to word petitions and the sorts of issues they might raise. By the standards of British bureaucracy, it is user-friendly and responsive.

There is no doubt that the e-petitioning system has attracted a lot of users. The website reports that it has received 46,647 petitions, although the fact that 35,501 of these were rejected suggests that there is refinement to be made (the rejections were for all sorts of reasons, from relating to something outside the direct responsibility of government or parliament, through being unclear or duplicating an existing petition, to being submitted with an incomplete or fake name. Given that reasons have to be provided for every petition rejected, this process is a substantial undertaking. The argument goes, however, that it has hugely enhanced the House of Commons’s ability to connect with the electorate.

After its first year, the Petitions Committee published a report, Your petitions: a year of action, which rehearsed the arguments in favour of having created the system and (understandably) described how successful it had been. “Between July 2015 and July 2016, over 10 million unique email addresses were used to sign petitions in the UK. In total, there were over 20 million signatures on petitions.” This is a substantial level of interest. The report made the usual, necessary cautions that for the subject of a petition to be debated in Parliament did not mean that action would flow from this, but it was still very upbeat about this new outlet for the public’s views to be aired.

Raising your issue through a debate in Parliament is a great step for any campaign. You should never underestimate the power of making the Government defend its position, or respond to an issue it might not otherwise have been thinking about. It’s also a great way to raise the issue amongst MPs, who can then continue to press the Government for action even after the debate has finished.

All of this is earnestly executed work, done diligently by talented people, some of whom I still know. And the House of Commons clearly was right to engage with emerging technology in the 2000s to allow petitions to be established and managed outwith the old paper-based system. I have a default setting which leans towards conservatism and the maintenance of tradition, and my colleagues knew and largely tolerated that, but I am conscious that an old-fashioned institution like Parliament, if it is to be able to retain its grandeur and traditions, must be alive to the fine line between dignity and pomposity. That was why, as I wrote in November last year, I thought the House of Commons authorities were quite right to allow the Youth Parliament to sit in its chamber, and why I regarded those who objected as failing to see the world beyond the boundaries of the Parliamentary Estate.

I am also acutely aware, having spent a bit of time in reputation management, that expectations are very fragile and must be cared for with delicacy. And I do wonder if the way in which the e-petitions system, though it is easy to see the apparently logical steps which have got us to where we are, raise the hopes of the electorate that a new way to make a real impact in politics has been opened to them. The Petitions Committee lays out the criteria necessary for an orderly petition, and does it well, but the requirements are not without kinks or wrinkles. For example, “Petitions must be about something that the Government or the House of Commons is directly responsible for.” Seems reasonable enough, but I’ve been a political obsessive for 30 years or so, and I’d need to check in some cases whether the responsible body was a department, or a non-ministerial department, or an arm’s-length body, or an executive agency, and I approach this as someone who knows the landscape and the jargon, and who knows where to start looking for the answer.

Removing the mediation of a Member of Parliament, who would present a petition under the paper system, has certainly widened access, but it has also stripped out a layer of expertise or at least knowledge of where to go for advice. It is surely not a coincidence that three-quarters of all petitions are rejected, even if there can be many reasons for that, but it adds up to create a somewhat misleading picture of what is happening. I fear that many voters and participants in the petitioning process would be profoundly disappointed if its limits were clearly explained, and might well feel short-changed.

I nurse a concern that one narrative ion our politics for 15 or 20 years is that the faults, institutional, cultural or personal, which we can all identify are purely the responsibility of the political class to address. The voters should just wait to receive the revelation of a better, more open, more equal world, when they will smile indulgently and let our politicians know that finally, finally they have redeemed themselves. But it cannot work like that. Politics is a conversation, a dialogue: as the aphorism has it, bridge-building is a two-way street. I emphasised this in a recent essay on the central importance of trust and good faith, and it applies in the case of petitions too.

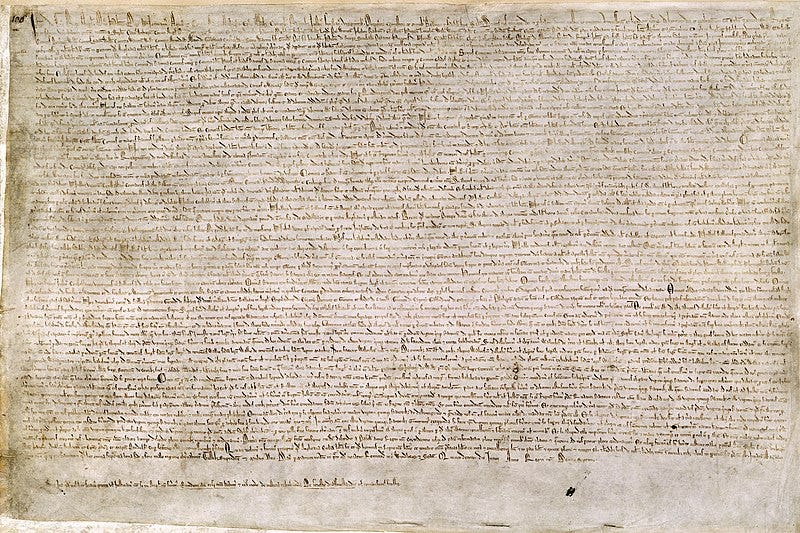

The House of Commons was right to see the subject of petitioning, which was, after all, for centuries the only effective way in which the people could engage with their elected representatives on their own ground, as fertile ground for public engagement. The right of subjects to petition the monarch for redress of personal grievances is reiterated in Magna Carta, so was at least being debated that long ago, and the first extant petitions are from the reign of Richard II (1377-99). This entitlement was affirmed by two Resolutions of the House of Commons in 1669. The concept, therefore, was venerable and valuable. It must be a fundamental entitlement of a voter to have a channel to go to the elected legislature and say, Here, look, this is an issue for which you are responsible and in which I have a problem: please help.

Human beings are complex organisms, and managing them effectively is challenging and sometimes counter-intuitive. I strongly believe that there are few neater ways to arouse anger and resentment among the electorate than extending the prospect of a right and then taking it away or allowing them to discover that it is made of a metal much baser than the gold it appeared. In connection with this, we must understand, while we can regret, that most voters devote very little time and attention to what they consider “politics”, and we simply cannot expect even those sufficiently motivated to begin a petition to understand, as if by instinct, the complexities of how a petition works and the effect it is likely to have.

When we look at some of the most heavily subscribed petitions, we see what little prospect there is of a response or consequential action which would be regarded as satisfactory. A petition started in February 2019 to revoke Article 50 and have the United Kingdom remain within the European Union was eventually signed by more than six million people. It has not “stopped Brexit”. A 2016 petition demanded a threshold for the referendum on EU membership, making it effective only if more than 75 per cent of voters participated on both sides, and more than 60 per cent voted in favour of leaving. It gained 4.2 million signatures, but was not implemented by the government nor were its provisions respected. The result of the referendum stood.

The pattern is repeated again and again. 1.8 million people signed a 2007 petition (on the Downing Street website) to abandon road pricing, but Tony Blair politely but firmly declined to accept the recommendation. Petitions to deny President Donald Trump entry to the United Kingdom, and to legalise cannabis (was there a link?) attracted support well into six figures, but were disregarded by the government. This recurring pattern of substantial sections of opinion being able to leverage the e-petition system well enough to achieve high numbers of signatories, but then almost all petitions on major matters coming to nothing in legislative or policy terms, suggests, however inadequate, the Commons has created a kind of displacement activity for the voters. But the dangers are obvious.

Some of the greatest seismic political shocks of recent years, from the success of the Brexit referendum to the hearty victory of Boris Johnson and his government over the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn, have owed a great deal to disenchantment, disenfranchisement and a widespread feeling among voters that they no longer have any agency to affect the political process. It would be the most perilous hostage to fortune if the necessarily modest system of e-petitions were sold to the British people as a revolution in the relationship between the governing and the government. We need to treat petitions as pinpricks on the hide of the policy elephant: each assailant might feel important, but the overall effect is minimal. Petitions are, effectively, a way of angry voters to let off steam.

Reform is hard. If there is a policy elephant, then it was apposite of the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu to say “there is only one way to eat an elephant: a bite at a time”. When we make a change which we think will be an improvement, we should be resolute but realistic: on its own, the change will not transform politics. But if walk gingerly, tread softly, and speak honestly, we can benefit from those bites of the elephant. A forkful of elephant meat is not a sirloin steak, so let us act in good faith and make sure that the voters and the government move forward together, each having agreed where they are going and the relative merit of the destination a matter of consensus. If we let the voters race ahead, they will eventually realise they are alone, and we know what their reaction will be.