Len Deighton: Britain's most underrated writer?

He is 95 and living contently in retirement but his contribution to Anglophone literature and film is enormous and under-recognised by many

“The best thing about writing books is being at a party and telling some pretty girl you write books, the worst thing is sitting at a typewriter and actually writing the book.”

That was how Len Deighton summed up his profession when he appeared on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in June 1976. I had been thinking about writing and being a writer, and had begun to form some thoughts which I intended to turn into words, when I was reminded of Deighton’s quip and laughed out loud. It was hard on the heels of the most recent meeting of The Writing Salon, the monthly creative writing group in Soho I’m part of, at which we’d been talking about the espionage genre, and a repeat of the relevant episode of Sleuths, Spies and Sorcerers: Andrew Marr’s Paperback Heroes on BBC4. It made me realise that I should actually write about Len Deighton.

Len Deighton turned 95 earlier this year. His last novel, Charity, was published in 1996, the ninth and final book of the cycle of Bernard Samson novels which began in 1983 with Berlin Game. For me, it’s one of the great achievements of post-war British fiction, complex, multilayered, analytical, moving and exceptionally evocative of the last years of the Cold War and the early years of the era that followed. In 2006, he contributed a short story, “Sherlock Holmes and the Titanic Swindle”, to The Verdict of Us All: Stories by the Detection Club for H.R.F. Keating, but that light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek homage to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and his legendary consulting detective was the last fiction he published. In 2012, he wrote James Bond: My Long and Eventual Search for His Father, a slender but priceless examination of the evolution of Bond which was issued as an e-book only.

One can hardly blame Deighton. He turned 67 the year Charity was published, a more than respectable retirement age, and he could look back at 26 other novels, a collection of short stories, 15 non-fiction books and (uncredited) the screenplay for Richard Attenborough’s 1969 directorial debut Oh! What A Lovely War. Because he has lived abroad for more than 50 years, does not frequent literary festivals and dislikes giving interviews, Deighton essentially vanished from public view, and what few indications he has given are that he is very happy with such a state of affairs. In a rare encounter for BBC Radio 4, The Deighton File, in 2006, he told Patrick Humphries that he had come to the conclusion that writing was “a mug’s game” and he didn’t miss it. He had certainly put in the hours to earn that decision.

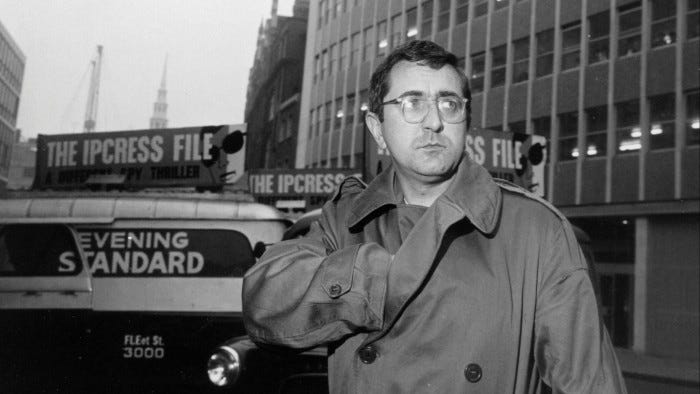

Despite this prodigious output, I have the impression that many people would not recognise Deighton’s name or his bibliography, or perhaps have a vague sense of him as a thriller writer responsible for the iconic 1965 Michael Caine film The Ipcress File and the six-part television adaptation of 2022. I’m willing to bet he comes to most people’s minds less readily than Ian Fleming or John le Carré or Frederick Forsyth or Charles Cumming or Mick Herron. I have no doubt that the man himself is supremely unworried about this if it has ever occurred to him at all, but it bothers me, because I have loved Deighton since I was an adolescent and continue to do so, and will happily assert that he is one of the best and most influential writers of espionage fiction this country has produced. More than that, he is an exceptionally versatile talent, a keen historian and gifted draughtsman and illustrator: more fundamentally, though, he is one of our best authors of fiction, full stop.

We like the idea of “genre fiction” because it is an easy and helpful taxonomy for readers and publishers: crime, thriller, science fiction, fantasy, romance, horror, historical. It effectively does some initial thinking and selection for us, and is an essential tool in the armoury of those who tend the commercial side of fiction, but the reverse of that is that it narrows and limits, and there has long been a vague sense that it is the second division of fiction, the Championship to literary fiction’s Premier League.

The barriers are not impermeable. Both critics and readers now would, I think, happily count the late Dame Hilary Mantel as an author of the first rank, rather than relegate her to the genre of historical fiction, and recognise Wolf Hall, Bring Up The Bodies and The Mirror and the Light as great British novels (the first two winning the Booker Prize and the third being longlisted). Sir Philip Pullman has probably also made the leap, the His Dark Materials trilogy sufficiently popular and lauded to have escaped the gravitational pull of the fantasy genre. The renewed focus on John le Carré (David Cornwell) in the three and a half years since his death, including a posthumous novel, Silverview, Adam Sisman’s brilliant biography and the publication of a collected volume of letters, A Private Spy, have marked his confirmation as a literary legend, not that it should have needed any confirmation.

Deighton has not made that leap. Without a public profile, I suppose it is unlikely. He has never been a conventional author in any event. You can read in any number of places about his fascinating early life, born in a workhouse to parents who were in service, training in photography during his National Service with the Royal Air Force, winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art, working as a pastry chef at the Royal Festival Hall and becoming a professional illustrator.

When Melvyn Bragg interviewed Deighton for the BBC’s The Lively Arts in 1977, he spoke revealingly of his introduction to the world of writing. He had begun writing what would become The IPCRESS File, his first novel published in 1962, as a “story” to amuse himself while on holiday in the Dordogne, drawing on his interest in and knowledge of espionage as a context. But he makes the telling observation that most writers who embark on a novel have some experience of writing, whether as academics or journalists or civil servants, while he had virtually none. He didn’t know that novels were typically between 80,000 and 100,000 words, nor did he have any conception of what that meant or represented in terms of effort. He knew nothing about plot development or characterisation, let alone structure and rhythm. Echoing Orson Welles’s explanation of the brilliance of Citizen Kane deriving from his not knowing what was impossible, Deighton describes how he simply began writing his “story” and ended up with a novel.

And what a novel. Hodder and Stoughton published The IPCRESS File in November 1962: the timing is important. It was only two months after le Carré’s second novel, A Murder of Quality, had been released, again featuring retired intelligence officer George Smiley. Additionally, it was only a month after the world premiere of the first James Bond film, Dr. No, at the London Pavilion. Ian Fleming had already published nine novels featuring the sophisticated and aspirational 007, and in April 1962 he had published a collection of short stories, The Spy Who Loved Me. (Fleming was ailing by this stage, having suffered a heart attack the previous year, and would die in August 1964.)

Espionage-leaning thrillers were very much in vogue: Eric Ambler, one of the masters of the genre, had published The Light of Day, his 11th novel, to positive reviews, while Alistair MacLean, writing under the pseudonym Ian Stuart to prove his books were successful because of their content rather than his imprimatur, explored the dangers of biological warfare in The Satan Bug. The idea of mind control, so central to The IPCRESS File, had been given the Hollywood treatment a month earlier with the release of The Manchurian Candidate, John Frankenheimer’s tense, star-studded adaptation of Richard Condon’s 1959 novel.

All of this was happening against an acutely tense geopolitical backdrop. The United States had introduced a trade embargo against Cuba in February, the same month that captured U-2 spyplane pilot Captain Francis Gary Powers was released by the Soviet Union as part of a prisoner exchange. And the very month before the publication of The IPCRESS File, the world had skated dangerously close to nuclear armageddon in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The social milieu is important too. By the end of 1962, Harold Macmillan’s premiership was looking fragile. He had attempted to revive his fortunes that summer with a dramatic cabinet reshuffle, dismissing seven ministers, but a leak in advance by his deputy, Rab Butler, had thrown the timing into disarray and the end result looked desperate and brutal. The rising Liberal star Jeremy Thorpe had summed up the prime minister’s predicament when he had observed acidly, “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life”. Macmillan was a 68-year-old Old Etonian who had studied at Balliol College, Oxford, and served in the Grenadier Guards in the First World War. He looked increasingly incongruous appealing to a nation which had just heard “Love Me Do'“, the debut single by the Beatles, was enthralled by the gritty realism and authentic dialogue of Coronation Street and had recent memories of the defeat of the Establishment and its staid values in the Chatterley trial of 1960.

This is why The IPCRESS File was a bombshell. It planted itself firmly on Fleming’s turf of Cold War espionage, but its narrator (unnamed; “Harry Palmer” was an invention of the 1965 film adaptation) was a combative, insubordinate, witty and bespectacled working-class NCO from Burnley. He hates but understands the mind-numbing bureaucracy of the intelligence services, having just been transferred from military intelligence to the fictional WOOC(P), a civilian organisation under Major Dalby which reports directly to the cabinet. He is also sophisticated and well read, unusually interested in cooking, referring to Kierkegaard and Brecht and listening to jazz by Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughan and Charlie Parker.

The IPCRESS File is a gripping thriller, but it is also a savage and thorough dissection of the class system of Britain in the early 1960s. The narrator’s tastes in literature, music, food and coffee are distinctive enough to combine aspiration, enthusiasm and provocative cosmopolitanism. He has scant respect for the traditional establishment. At one point, he describes how “Corrugated iron manufacturers and chinless advertising men shared the joys of our expense-account society with zombie-like debs with Eton-tied uncles”.

The narrator’s description of a well-bred young subordinate, Phillip Chillcott-Oakes, is eviscerating, funny and all too recognisable.

Chico always looked glad to see me, it made my day; it was his training, I suppose. He’d been to one of those very good schools where you meet kids with influential uncles. I imagine that’s how he got into the Horse Guards and now into WOOC(P) too, it must have been like being at school again. His profusion of long lank yellow hair hung heavily across his head like a Shrove Tuesday mishap. He stood 5 ft. 11 in. in his Argyll socks, and had an irritating physical stance, in which his thumbs rested high behind his red braces while he rocked on his hand-fasted Oxfords. He had the advantage of both a good brain and a family rich enough to save him using it.

The nuances of class and its hold on society are captured in a typically brilliant Deighton epigram when the narrator notes that there is brass band music audible in an office below Major Dalby’s. “It made Dalby feel he was overlooking Horse Guards Parade; it made me feel I was back in Burnley.”

In a few sentences on the first page, Deighton says more about the administration of the British state as it really was in the early 1960s than Fleming, for all his wartime service in naval intelligence, ever did.

They came through on the hot line at about half past two in the afternoon. The Minister didn’t quite understand a couple of points in the summary. Perhaps I could see the Minister.

Perhaps.

This secret work takes place not in some grand, colonnaded department redolent of empire, but a shabby house on Charlotte Street, “one of those sleazy long streets in the district that would be Soho, if Soho had the strength to cross Oxford Street”. To make the point, the building, which has several rather shady and disreputable occupants, is next door to “a new likely-looking office conversion wherein the unwinking blue neon glows even at summer midday”.

Deighton is often credited with creating an “anti-Bond” in his unnamed narrator. Certainly the protagonist of The IPCRESS File fits that description, but the tag incorrectly implies causation. Deighton had not set out to create an alternative fictional polarity to Fleming’s 007 but instead to shine a light in Britain as it was from the perspective of below rather than above. While Bond, a wealthy, public school-educated (although orphaned) naval officer at home in the clubs of Pall Mall and the casinos of Mayfair, could afford to regard his surroundings with detachment, he saw an essentially benign atmosphere in which his place was secure. Deighton’s narrator saw instead a hollowed-out bureaucracy still in the grip of the upper and upper-middle classes, with advantages on offer to the inadequate but well-connected, and an inability to fend off decline and decay.

John le Carré is rightly celebrated for his gritty espionage thrillers, born of time spent working first for the Security Service (MI5) then the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, or MI6). He depicted a much less clearly defined moral universe than that of Bond, one of compromise and accommodation, of doubt and anxiety, exquisitely depicted in The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and, perhaps most of all, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. But le Carré was to some extent an insider himself. Not only had he served with both the domestic and foreign arms of the British intelligence community, he had been educated at Sherborne School and Lincoln College, Oxford, where he had been a member of the prestigious Gridiron Club and his college’s own exclusive Goblin Club. He had then taught modern languages at Eton for two years.

Deighton had done all of this revolutionary work, he had done it from a background lacking privilege or advantage, and he had done it in one single, dazzling, tense, witty, barbed 224-page punch. And it was a brilliant commercial and critical success from the beginning. The cinema adaptation—produced, let us not forget, by Harry Saltzman, who was co-producer of Dr No and the subsequent eight Bond films—followed swiftly and the novel has sold more than 10 million copies. If he had done nothing else, Deighton would deserve a prominent place in the pantheon of post-war British authors for a work which was not only brilliantly written and observed, but acutely relevant and perfectly timed.

“Nothing else”, however, hardly applies. There were three more “Harry Palmer” novels in quick succession, Horse Under Water (1963), Funeral in Berlin (1964) and Billion-Dollar Brain (1966), the last two also adapted for the screen with varying success. In 1970, he published Bomber, the fictional account of a Second World War raid by RAF Bomber Command which was based on meticulous and exhaustive research. Following the bomber crews, their families and the ground staff at the airbase, the inhabitants of the fictional German town of Altmarkt in the Ruhr and the personnel of Luftwaffe night fighter units based in the Netherlands, it exposes in pitiless and heart-wrenching detail over 500 pages the human horror of the bomber campaign and the appalling suffering it caused. For my money, it is one of the best and most insightful books, fiction or non-fiction, about the Second World War.

Deighton also made a very skilful and plausible contribution to the now-booming field of alternative history with SS-GB (1978), a detective thriller set in a Britain which had surrendered to Germany in 1941. Churchill has been court-martialled and executed in Berlin, George VI is imprisoned in the Tower of London and Queen Elizabeth and her young daughters, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, have fled to New Zealand. A government-in-exile led by (the real) Rear Admiral Conolly Abel Smith, a former equerry to the King, has been established in Washington DC, as the United States being a neutral power, but it lacks widespread recognition. The BBC produced an five-part television adaptation of the novel starring Sam Riley and Kate Bosworth in 2017.

SS-GB was by no means the first alternative history novel. Keith Laumer’s Worlds of the Imperium (1961) had approached the idea from a science fiction perspective, with a protaganist discovering parallel worlds, while the following year Philip K. Dick had imagined a Second World War in which Imperial Japan had been victorious in The Man in the High Castle. Vladimir Nabokov’s strange and ambitious Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (1969) had taken place in a North America which had been settled by Tsarist Russia, while Kingsley Amis set his The Alteration (1976) in an alternative world in which the Protestant Reformation had enjoyed much less widespread success and is limited to the Republic of New England, while Europe remained Catholic.

Deighton did something different again, something more striking and perhaps more influential. In SS-GB, he took one of the most perennial propositions of alternative history—what if Britain had lost to the Nazis?—but, rather than examine it directly, he used it as the warp and weft of a police procedural. It was a stroke of genius, humanising a potentially dry theoretical exercise and allowing different perspectives on and approaches to the million tiny ways in which ordinary life would have been different, and the small compromises that a defeated nation is forced to make to exist under occupation. It is safe to say that, without SS-GB, Robert Harris could not have written his iconic and best-selling Fatherland (1992).

There have also been scholarly, well-argued volumes of military history. Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain (1977) was the product of encouragement from Deighton’s friend A.J.P. Taylor, the great historian and broadcaster, who contributed an introduction. Not only does it combine strands of military, political, personal and technological history, it looks behind many myths then still prevalent about the period and champions the achievements of Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding, head of RAF Fighter Command (1936-40), who was effectively scapegoated for British failures and sidelined shortly after the beginning of the Blitz, first to the United States as an envoy of the Ministry of Aircraft Production and then as head of an inquiry into RAF manpower, before retiring in July 1942.

In 1978, he released Airshipwreck, a expertly written analysis of that short period between 1912 and 1937 when dirigibles seemed a potential future of air travel and aerial warfare. A year later Deighton brought out Blitzkrieg: From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk, which drew on interviews with Allied and German participants and used his mastery of technical detail to give a compelling account of the early military successes of Nazi Germany and the initial intuitive leadership of Adolf Hitler. 1993’s Blood, Tears and Folly: An Objective Look at World War Two was an attempt to examine in a comprehensive way the events leading up to the Second World War. At more than 800 pages, it covered an enormous amount of ground and was praised for the breadth of its perspective.

In addition to all of this, there is what I think is his multi-volume masterpiece, the three Bernard Samson trilogies of Game, Set and Match, Hook, Line and Sinker and Faith, Hope and Charity (as well as the allied prequel-cum-family saga, 1987’s Winter). Published between 1983 and 1996, they are on one level a magnificent evocation of the business of spying as the Cold War thaws and comes to an end, and spies who knew their place in the order of things have to adapt to a new and rapidly changing world. Picking up from the four Harry Palmer novels, they are also a sharp and sometimes satirical depiction of the flaws of bureaucracies, especially British ones, and the foibles of the individuals who operate them. They also provide a loving and painstaking portrait of Berlin over the course of the 20th century.

I think they are something more profound than that, too. In a preface to a 1986 omnibus edition of Game, Set and Match, he describes dwelling on the idea of betrayal: if a man could betray his wife, would he betray his country? From there blossoms a meditation on human nature and the strength of human relationships, which are, after all, the component parts from which espionage is constructed. Spies, intelligence officers, agents, double agents, moles, spy hunters: all of these carry out their roles because of some kind of bond of loyalty, or a bond of loyalty broken, and these bond have different strengths and longevities. Connected to that, and displayed to agonising perfection across the span of the novels, is the cost of state policy on the men and women who carry it out. It is not just the physical cost, though the body count is high enough and there are some shocking deaths, but the emotional cost: what does serving your country in the shadows where espionage takes place do to your soul and your psyche?

We see most of this—of the nine novels, only Spy Sinker is in the third person—through the eyes and the prejudices of Bernard Samson. We know, we are told, that he is an unreliable narrator, but that tells us much more, in fact, than if the whole cycle were a straightforward third-person narrative. By casting Bernard as narrator, another echo of The IPCRESS File and its sequels, Deighton shows us the story as it happened, as if we were there, with an immediate but necessarily partial field of vision, rather than making us god-like observers who can scan the panorama of events. It is an extraordinary achievement of storytelling, and its brilliance is doubled by the sixth novel, Spy Sinker, when we are taken back through the events we have experienced with Bernard but now from a new perspective. We see where there were gaps, where there were movements behind the scenes, and we see where Bernard was mistaken or deceived, and where he deceived himself.

Taken as a whole, the ennealogy—yes, that’s a nine-part work, though Winter makes it a decology if you want to include it—does so many different things. It is, unapologetically and importantly, an outstanding spy story, capturing the essence of East-West tensions and rivalries as the 1980s progressed and gave way to the 1990s. Within that, it is a vivid and witty sketch of internal bureaucratic politics of a peculiarly British kind, and, as in Deighton’s earlier work, a masterful portrayal of the subtleties of the evolving class system and its part in those politics. It is also a fantastically rich and involving character study of divided Berlin, a city traumatised by war, savaged in its aftermath and then used as a theatre to play out the Cold War in microcosm, especially after the Berlin Wall (or “Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart”, Antifaschistischer Schutzwall) was begun in 1961.

Like all great literature, though, the Samson novels are a story of human nature in adversity, its resilience and its limits. They show you “what it was like to be there” in small, clever, practical ways, with tricks and techniques of spycraft and impenetrable bureaucracies, but on a much deeper level it shows you what it means to work and live in the shadows, to exist in a world where the truth is always a compromise and a transaction, where trust is always qualified and no-one ever sees the whole canvas. And the effect of that is a price demanded and paid, and casually devastating.

Len Deighton did all of this, and he did it all in a career which really only lasted 35 years, before he effectively withdrew into happy retirement and anonymity with his wife Ysabele. As an author of espionage fiction he is at least as significant as Fleming and le Carré, and much of what is attributed to the latter in shaping the genre—stripping away the glamour, showing post-imperial decline, exposing internecine bureaucratic wrangles, portraying moral compromises—was done just as much, and in some cases earlier and more fully, by Deighton than by le Carré. Some critics have accused him of having not a prose style but a prose strategy, but I think that undervalues his use of language: some of the observations and epigrams are tiny, perfect, cutting jewels of observation, and Deighton always writes with a distinct and discernible but relentlessly dry humour.

We all live in Len Deighton’s world, in small, occasional but accreting and influential ways. Gritty, sardonic Northern humour? Check. Hard-bitten, unsentimental, transactional and brutally realistic spies? Check. A lingering inheritance of a shabby, uncertain, post-imperial identity crisis? Check. Men who love cooking and music and culture but “like birds best”? Check. He has had so many careers, all pursued brilliantly and in parallel, and it would do us good to revisit them from time to time.

“In 1970, he published Bomber, the fictional account of a Second World War raid by RAF Bomber Command …For my money, it is one of the best and most insightful books, fiction or non-fiction, about the Second World War.” I absolutely agree. I still imagine the horrors of some of the scenes from the book 50 odd years after first reading it. Something about the fictionalising of the events, giving them a case of identifiable characters, makes it so much more gut-wrenching than any academic history does. For me, HMS Ulysses by Alistair MacLean has the same effect. My father, who served in the RN as a DEMS gunner on various convoys during WWII but rarely spoke of his experiences (which did include at least one torpedoing and one sinking, but also sailings to Sydney, Cape Town and New York) did comment after reading this story of the Arctic convoys that he was very glad that he was never assigned to the Russian runs.

Thank you for this very good overview of Deighton’s career.