John Biffen and reflections on the House

Very few ministers are remembered primarily for their time as Leader of the House of Commons; a glance at Biffen and some related observations

In one closing-of-the-year tweet, John Oxley, who emerged rapidly during 2022 as a perceptive and always-interesting commentator on conservative politics, was kind enough to mention me in a list of people whom he’d got to know and whose output he enjoyed over the preceding year. He named me as someone “whose parliamentary trivia knowledge shames us all”, which is generous, but I do have the unfair advantage of it having been my job for more than a decade, let alone a deep-seated obsession since my teenage years at least. And for me it’s like a rhetorical ear worm: if I’m watching the live coverage of a debate in the Commons, I will from time to time act as my own Mr Speaker, chiding Members or encouraging them to brevity or relevance. I can’t help it; although I admit I don’t try very hard.

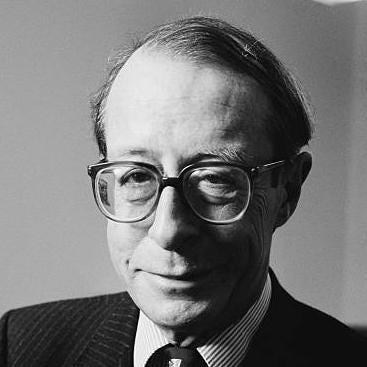

I’m currently re-reading John Biffen’s Inside the House of Commons: Behind the Scenes at Westminster. It’s a vivid but broad-brush pen portrait of the House based mainly on his five years as leader of the Commons between April 1982 and June 1987. (He replaced Francis Pym when the latter became foreign secretary in the wake of Peter Carrington’s resignation over the Falklands crisis.) It’s a very elegant, enjoyable book, though I don’t know what a civilian would make of it; some of the more basic descriptions I skim because I know the material, but the anecdotes are well-chosen and well-told, and I have stored many of them away in my reliable memory banks.

Biffen was a peculiar man in some ways. He was elected at a by-election for Oswestry in November 1961, the sitting Member, Sir David Ormsby-Gore, having been appointed ambassador to the United States. Biffen was cut from very different cloth from his aristocratic, well-connected society predecessor (who would in 1968 propose marriage to his old friend Jacqueline Kennedy). The son of a tenant farmer, he had attended a grammar school in his native Bridgwater in Somerset, then won a scholarship to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he was awarded a first in history. He was ferocious intelligent, but, unlike many who share that distinction, a quite strikingly nice man. Philosophically, however, he was hostile to the Keynsian economic consensus, drawn instead to the same proto-monetarist beliefs that Enoch Powell was beginning to espouse, and was one of the 15 Conservative MPs to vote for Powell in the 1965 leadership election.

It took Biffen many months to make his maiden speech. When he did, on Thursday 26 July 1962, it was in a confidence debate called by the opposition, following the widespread, controversial reshuffle the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, had carried out a fortnight before, sacking some of his closest allies in cabinet. (The Liberal leader, Jeremy Thorpe, wins the prize for the best line on the ‘Night of the Long Knives’, as the reshuffle was dubbed: “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life.”) Maiden speeches are supposed to be uncontroversial, and Biffen did his best, but he marked himself out as a witty, accomplished and articulate speaker, flagging his economic views and generally progressive identity. He took a gentle swing at the combative Labour veteran Manny Shinwell (Lab, Easington) who had first entered the House 40 years before, and was not above twitting Hugh Gaitskell (Lab, Leeds South), the leader of the opposition.

Given his unorthodox (for the early 1960s) economic views, Biffen found little favour with the leadership of Edward Heath. Worse, he was an early Eurosceptic, voting against the European Communities Bill in 1972 at both second and third reading. The accession of Margaret Thatcher as leader of the Conservative Party opened the door to Biffen, and she appointed him energy spokesman in July 1975 and shadow industry secretary at the end of 1976. But he was, unbeknownst to his colleagues, suffering from severe depression. It had first afflicted him in the early 1960s, without warning, though he later wrote “I had been a nervous child—highly strung was the meaningless phrase—and had to be coaxed through examinations.” (It is an acutely familiar description to me.) In 1977, he admitted his illness to Thatcher. With the characteristic kindness which her detractors rarely admit, she told him to take some time away from his shadow cabinet duties and find a way to get better. A doctor prescribed him lithium carbonate, and within months he was back at his post, substantially improved.

Despite his ideological sympathy with Thatcher’s approach to the economy and Europe, Biffen was not a ministerial success, first as chief secretary to the Treasury (1979-81) then secretary of state for trade (1981-82). In her 1993 memoirs, Thatcher commented with fairly lofty disdain that he:

had been a brilliant exponent in Opposition of the economic policies in which I believed... But he proved rather less effective than I had hoped in the gruelling task of trying to control public expenditure.

Perhaps that was true. But he shared little with Thatcher apart from her broad principles. She was intelligent but very definitely not an intellectual, while Biffen was questioning, sceptical, curious and humane. His progressivism, which he had signalled in his maiden speech in 1961, led him to side with the trades unions at GCHQ when they went on strike in 1981, Thatcher arguing fiercely that it was irresponsible and compromised national security. The same year, at a fringe meeting, he mused publicly that the government, at that point going though severe unpopularity because of the economic climate, was “within touching distance of the débâcles of 1906 and 1945”, hardly the sort of mood music cabinet ministers were supposed to broadcast.

When Lord Carrington resigned from the Foreign Office at the opening of the Falklands crisis in April 1982, Biffen became leader of the House in the ensuing reshuffle. He had found the job which fitted him like a bespoke suit, which he enjoyed and at which he was brilliant. I wrote last November about the role of the leader, and it is a singular one: the holder is simultaneously the cabinet’s ambassador to the House and the House’s ambassador to the cabinet. The leader is responsible, with the chief whip, with the management of parliamentary business, but also has a more consensual role in dealing with all parties and representatives of the backbenches as well as the speaker. To do it well, it requires humour, patience, lightness of touch and flexibility, as well as a genuine belief in the importance of the House of Commons as an instrument of scrutiny and representation. Harry Crookshank (Con, Gainsborough) and Michael Foot (Lab, Ebbw Vale) were outstanding post-War leaders; Richard Crossman (Lab, Coventry East) and Chris Grayling (Con, Epsom and Ewell) were fairly disastrous. Biffen was widely seen as the best of the second half of the 20th century.

Obviously Biffen’s account of his five years as leader is dated. Politics is very different 40 years on, controversies have changed, and many of the procedures and traditions of the House have changed. Probably the aspect current MPs would notice most sharply is the different sitting hours: the House did not sit until 2.30 pm on Mondays to Thursdays, and consequently the business regularly continued into the evening, sometimes very late, and sometimes into the early morning of the next day. Legislation was not habitually subject to programme motions, so debate could only be curtailed by the use of allocation of time motions (otherwise known as “guillotine motions”) which were regarded as exceptional and not to be tabled as a matter of course.

Nevertheless, the book is more than worth reading for its encapsulation of the spirit of the House in the 1980s. It was a time at which there was a generational shift going on. The ranks of Members who had served in the Second World War were beginning to thin—I haven’t combed the archives exhaustively but the last veteran must surely have been former prime minister Sir Edward Heath (Con, Old Bexley and Sidcup) who retired in 2001, having risen to lieutenant colonel in the Royal Artillery—while the demographic of MPs was changing, becoming more middle-class, (slowly) more female and (very slowly) more racially diverse. The departmental select committees which Norman St John Stevas had established in 1979 were stretching their legs and becoming influential bodies in the political landscape. And the Labour Party had begun the long process of soul-searching and self-examination which would eventually culminate in Sir Tony Blair’s messianic new dawn of May 1997.

Biffen’s innate reasonableness made him a first-class leader of the House. But it would also be his downfall. He and Thatcher had drifted apart by the mid-1980s, and his opposition to what would become the Community Charge was a grave sin in the Lady’s ledger. In 1986, he said in a television interview with Brian Walden that the country would be hoping for a “balanced ticket” after the next general election. He also hinted that it would be a good thing if the prime minister did not serve the full parliament. Thatcher was furious, and had to be dissuaded from sacking him straight away (for all his courtesy and charm, Biffen was extremely unwise and rather foolish in saying such things publicly), while her press secretary, the congenitally blunt Bernard Ingham, dismissed him as a “semi-detached member of the government”. After the 1987 election, he was permanently detached, and spent another 10 years on the backbenches before retiring from the Commons in 1997.

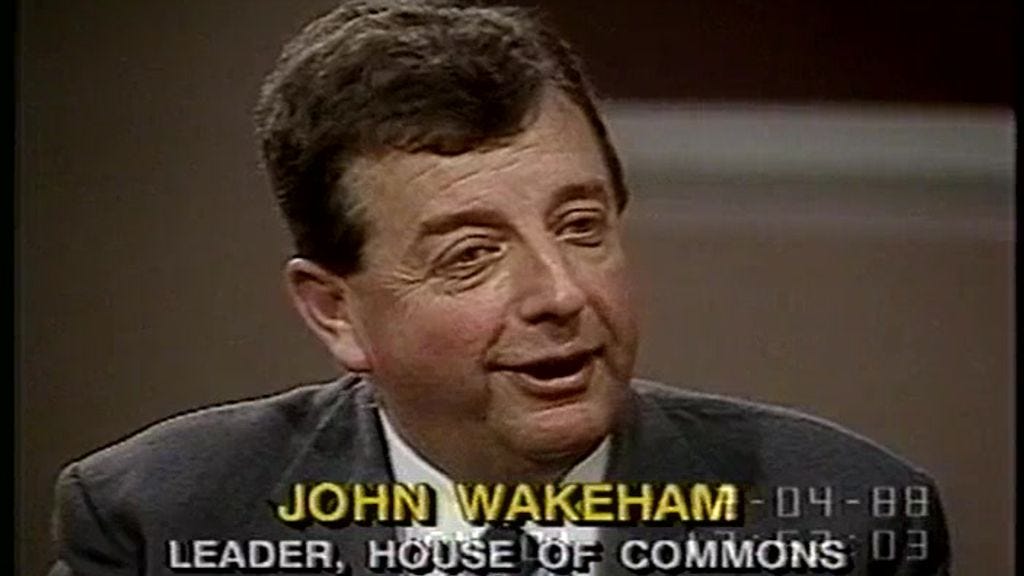

Biffen’s replacement as leader of the House was the former chief whip, John Wakeham. He had been a skilled business manager, sensitive to what would and wouldn’t pass the Conservatives’ parliamentary majority, but he spent some time away from the job after being badly injured in the IRA bombing of the Grand Hotel in Brighton in October 1984 (his wife was killed in the blast). His legs were crushed and for a while there was the possibility of amputation, but they were saved by the surgical team at the Royal Sussex County Hospital. Nevertheless he still walks with difficulty.

He would prove an effective leader of the House, securing the passage of a number of controversial pieces of legislation: the Education Reform Act 1988, which introduced the National Curriculum and created City Technology Colleges and grant-maintained schools; the Local Government Finance Act 1988, which brought in the Community Charge—the infamous and ill-starred “poll tax”—and business rates; and the Water Act 1989, which achieved the privatisation of the water industry. He also oversaw the preparations for televising the House of Commons, a measure which was inevitable after the Lords had taken the plunge in January 1985, hitting the headlines with a bravura performance by the 90-year-old Earl of Stockton, formerly Harold Macmillan. The first regular proceedings broadcast were the beginnings of the debate on the Queen’s Speech on 21 November 1989, and the first speech came from Ian Gow (Con, Eastbourne), who, although opposed to broadcasting, moved the Humble Address brilliantly: it is worth watching. Gow was murdered by the Provisional IRA a year later.

All of this has reminded me, and perhaps this is the only point I want to make, that I love the rhythm of the Commons. What accomplished parliamentarians—good speakers and effective chairs—realise is that the House is an organism when considered collectively. It has a tenor, a mood, a personality. If you can read that, feel it, sense it almost instinctively, you can be a master of the House of Commons. Enoch Powell observed that “For a politician to complain about the press is like a ship’s captain complaining about the sea”, but we might modify his dictum and see the chamber as the rolling, shifting waters of a sea instead. Certainly you can feel it swell and ebb, but it is generally predictable if you know the chamber and have read the Order Paper.

The chances of my becoming a Member of Parliament are as slender as can be, so slim that if they turn sideways you can’t see them. The auguries would not be promising: two former clerks have stood for the House of Commons, of whom the first, the Irish nationalist Erskine Childers, was executed by an Irish firing squad in 1922; the second, Robert Rhodes James, a brilliant brain but devoid of the glad suffering of fools, was Conservative MP for Cambridge from 1976 to 1992, but never achieved ministerial office and more or less drank himself to death, disappointed.

(Rhodes James is ripe for a biographical study. He was a clerk for nine years, from 1955 to 1964, erudite, intelligent and quick-minded, a prize fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, when he arrived at Westminster, but devoted more to his historical writing than to the arcana of parliamentary procedure. Andrew Roth, writing his obituary for The Guardian, said he “never lost the superior manner commonly displayed by clerks of the Commons”, which may have been the case then but I hope is unfair now. He became friends with the Countess of Rosebery, and Tam Dalyell, recalling James’s life in The Independent, observed with his strange combination of fastidiousness and accidental wit:

It was the Rosebery connection which was at least one symptom of Rhodes James’s less than relaxed relations with his professional colleagues when he first arrived in the Commons. To regale senior and clever clerks with what had occurred over the weekend at Dalmeny and Mentmore was rather too grand for a young man’s own good. He injured his prospects by being thought a terrible name dropper.

James was the nephew. of the great Victorian and Edwardian ghost story writer M.R. James. After he resigned as a clerk, he devoted more time to scholarship, but also worked at the United Nations, serving from 1973 to 1976 as principal executive officer to the secretary-general, then the lanky petit bourgeois Nazi war criminal Kurt Waldheim. His biographies remain excellent, though some are showing their age, and he made a reasonable fist of the rather timid, bowdlerised first edition of Sir Henry “Chips” Channon’s diaries, now superseded by the full-disclosure, three-volume version edited by Simon Heffer.)

As I say, I am unlikely ever to grace the green leather benches, and would be anxious to challenge the fates of my fallen colleagues, but were I to do so I can quite see the attraction of being speaker, or one of the deputy speakers, or a member of the Panel of Chairs, senior MPs who chair legislative committees. I am not lacking in strong opinions, and I have politics generally of the right, but I could see the pleasure to be had from renouncing them, at least in part, and dedicating oneself to the business of procedure, as I did when I was a clerk.

But perhaps not. Members should not be clerks manqués, trying to bridge the divide between politician and official. They exist to exercise a political function, to bring that perspective and judgement to the work of the House, and the clerks exist to advise on the technical and regulatory aspects. According to Dalyell, Sir Donald Limon, clerk of the Commons from 1994 to 1997 (nicknamed “Tiger” and before my time), attested of Robert Rhodes James “that on no single occasion did [he] behave other than impeccably to his former colleagues in the Clerk’s department, not succumbing to the temptation to become a buff on parliamentary procedure”. That is as it should be, and shows both grace and judgement on RRJ’s part. So perhaps the unlikely nature of my transformation is a blessing. But I can still watch the chamber on television and mutter my own rulings and obiter dicta from the safety of my home.

" (The Liberal leader, Jeremy Thorpe, wins the prize for the best line on the ‘Night of the Long Knives’, ......"

Just to mention that Thorpe was not Liberal leader at this point. He had been elected at the previous General Election in October 1959 and became Leader of the Liberal Party in January 1967 when Jo Grimond retired. A small point I know!