In defence of "doctrine": why ideas matter

Sir Keir Starmer has promised a government "unburdened by doctrine", but that doctrine is just a pejorative word for ideas, and ideas are vital in politics

The names we choose for things reflect the way we feel about them. We all know this, but it is wittily summed up in Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn’s Yes, Prime Minister when Bernard Woolley, Jim Hacker’s principal private secretary, is talking about confidentiality in Whitehall.

Oh, that’s another of those irregular verbs, isn’t it? I give confidential press briefings; you leak; he’s been charged under Section 2a of the Official Secrets Act.

This is a phenomenon particularly prevalent in politics, in which appearances, outward form and taxonomy are hugely important. Look at France’s Rassemblement National, the party led for many years and still substantially controlled by Marine Le Pen. It rebranded itself in 2018, abandoning its original name of Front National because of its neo-Nazi associations, but we still describe its place on the political spectrum in ways which are influenced by our own views. Is it “far right”, “hard right”, “populist”, “nationalist”, “right-wing”, “anti-immigration”, “radical right”? It may be one or more, but the point is that when we choose a descriptor, we are presenting it as a supposedly neutral term but it is already weighted with meaning.

When Sir Keir Starmer made his first official address as prime minister outside 10 Downing Street on Friday, he promised to lead a “government unburdened by doctrine”. We all know what he means: he will be “moderate”, “centrist”, “practical”, rather than pursuing mad or damaging policies for ideological reasons. His words were carefully chosen, and he meant “doctrine” in a negative sense, as a rigid, arbitrary set of principles which are, by further implication, as often as not impractical and counter-productive. There is at least partially an unspoken comparison with the 49-day premiership of Liz Truss, which is portrayed by the Labour Party as an unthinking adherence to ideas which were inherently bad for Britain.

“Doctrine”, of course, has religious overtones, and it is worth reflecting that Starmer is the first prime minister openly to identify himself as an atheist (though several of his predecessors including David Lloyd George and Clement Attlee were functionally non-believers). We think of the broadest notion of Christian doctrine, or individual items of doctrine like the Holy Trinity or transubstantiation, or the Salvation Army’s Handbook of Doctrine. The important and derogatory element is that doctrine is not a set of conclusions reached by rigorous argument or testing of evidence but a collection of inflexible beliefs which must merely be accepted. To be “burdened” by doctrine as a politician, then, is to be unthinking, close-minded, impervious to argument or persuasion; it is an inflexible approach which cannot adapt to different and changing circumstances. Liz Truss, the narrative implies, failed because she brought a fixed doctrine and tried to shape the economy round it, whereas Starmer will succeed because he is pragmatic, will look at evidence and treat each issue on its own merits.

Etymologically, this is at best arguable. Doctrine is simply something which is “taught” (docere is Latin for “to teach”, giving us doctor or “instructor”), and there is no reason why doctrina should be inherently mistaken, inaccurate or unreasonable. I was taught Latin, physics and palaeography, and I don’t think I could simply have intuited them from first principles.

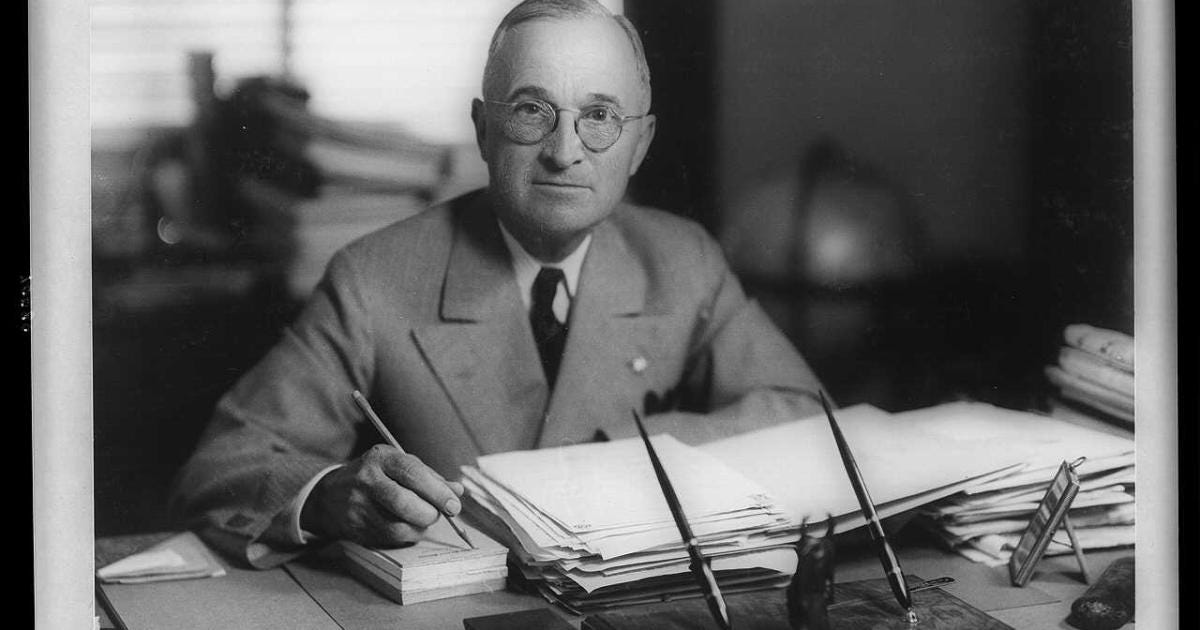

Doctrine also has a perfectly respectable political pedigree as a framing of ideas into a general approach to situations, especially in terms of foreign policy. The Truman Doctrine adopted by the United States in 1947 represented an assumption that America would assist democratic nations which were threatened by internal or external authoritarian forces, and was a useful statement of principle by the US government which sent a signal to the international community. But in no way did it result in America being compelled to intervene to support every state or face up to every dictatorship. Equally, the so-called Blair Doctrine which Sir Tony Blair outlined in his speech in Chicago on 23 April 1999 was an assertion of ambition, that liberal democracies could and should intervene in the internal affairs of other countries if it was the only way to save lives.

Starmer’s declaration that he is “unburdened by doctrine” is the culmination of an intellectual trend which began certainly as early as Blair’s leadership of the Labour Party. Partly in reaction to the stark ideological clash of the 1980s, and partly in recognition that the mainstream left had lost many of the important battles of that clash, Blair presented New Labour as post-ideological. He wanted people to see a political movement which wanted the best for everyone, which was maximally inclusive, which merely sought the most effective and efficient way of managing the British state. The Labour Party’s manifesto for the 1997 general election summed up this biggest of all big tents:

We are a broad-based movement for progress and justice. New Labour is the political arm of none other than the British people as a whole. Our values are the same: the equal worth of all, with no one cast aside; fairness and justice within strong communities. But we have liberated these values from outdated dogma or doctrine, and we have applied these values to the modern world.

That word “doctrine” again. This was the ultimate expression of what I term the “centrist fallacy”, the mistaken and corrosive notion that every political problem is amenable to a single, correct, effective solution which will be reached if enough people with enough goodwill spend enough time discussing it. I have touched on this issue before, here and here and here, and I think it is a notion which which is utter rubbish. I am all in favour of doctrine.

“Doctrine”, however slightingly the word was used by the prime minister, could equally be described as “values” or “philosophy” or “ideology” or even, mundanely, a “platform”. There was a time when we called them “-isms”: socialism, conservatism, liberalism, pacifism, protectionism, isolationism, Marxism, Thatcherism, even Blairism (the existence of which gives the lie to Blair’s idea of a post-ideological world). These ideologies are not only nothing to be ashamed of; I would go much further and say that they are beneficial and, indeed, essential to a coherent approach to politics.

Politics is not simply management or maintenance. It is not like being a mechanic and keeping a car in good working order, or rather, it is not just that; it is the conception and design of the car itself, and the understanding of its purpose. Everyone, however little we may admit it, and however confused it may be, has a doctrine or a philosophy, a way of looking at the world and a sense of how society should be ordered, and to what end. Not everyone will agree on these questions, and we should not expect them to do so, because we are not dealing with issues which can be resolved definitively in one correct way. We can and should argue passionately, fiercely but with courtesy about them, and sometimes we will persuade and convert, but that will not always be the outcome.

I have a political philosophy—a “doctrine”, if you like—and I am very happy to argue its merits and it is the one according to which I would like to see the country run because I think it delivers the greatest benefits not just in material terms but with regard to happiness and human dignity. I am a conservative and I believe in liberty and opportunity, in personal agency and autonomy and responsibility, underpinning which is a strong belief in free markets, private enterprise and free trade. I also believe in the power and benefits of tradition and institutions, and of evolution over revolution. Collectively those ideas make up my “-ism”, however you want to brand it. While I believe in it and will argue for it, I don’t expect to convert every interlocutor nor do I think it is the single, ineluctable, inevitable “truth” at which we will arrive by sufficient rational discussion.

By the same token, I unhesitatingly accept that people of integrity, intellect and good will see the world through a different lens, have different priorities and hold them to be as beneficial and high-minded as I do mine. I have always said, for example, that there is a position in favour of independence for Scotland which I respect without reservation, that Scotland, an old, identifiable and discrete polity, should be entirely self-governing. I don’t agree, and think that Scotland is better off for any number of reasons within the Union, but a Scottish Nationalist of that stripe and I can co-exist with perfect civility, simply accepting that our views on that principle are different and incompatible. Unfortunately there are many supporters of Scottish independence who cannot see that equivalence and must regard Unionists as “colonialist”, agents of English hegemony and enemies of the true interests of the Scottish people.

If you lack this intellectual framework, this set of principles about how society should be ordered and how the world is views, how do you approach politics in a coherent way? Of course there are some political questions which can be reduced to practical matters, but there are many which cannot, and the whole process must be much more difficult and confused if it does not stem from a “doctrine”, an ideology, a mindset. None of this has to mean an intellectual fixity which is impervious to reality: the notion of insisting mulishly on pursuing policies which are proven not to work is a caricature when applied to any part of the political spectrum. But deep thought, consideration of politics as a whole, a sense of purpose and vision—all of these things matter and are a good thing.

This touches on a critical matter for the future of politics. It is now accepted, to the point of being a commonplace, that politicians and political institutions are hugely discredited in the eyes of the public. Last year’s Ipsos Veracity Index showed that only nine per cent of those surveyed trusted politicians to tell the truth, the lowest score in 40 years. A 2020 study highlighted the importance of authenticity, which can take a number of form, but I don’t think it is fanciful to say that it is more difficult for a politician to show authenticity and integrity if he or she has no visible ideological moorings or overarching sense of principle. Competence is necessary but not sufficient: our leaders cannot simply say that they will be able to solve a problem through managerial and technocratic ability (and relying on that alone is an enormous hostage to fortune).

For all that many public figures like to champion consensus and compromise, politics is ultimately about debate—it is about disagreement but also persuasion, reasoning, emotion and, crucially, an acceptance of the outcome of the process. There is something dreadfully impoverished in intellectual terms about a bidding war for supposed technocracy: if politicians are asking for the opportunity to govern the country, asking essentially for the electorate’s trust for a period of four or five years, it is reasonable to ask how they see the world, what their values are and the vision of society they have. To dismiss this as “doctrine”, something which is a “burden” and by implication a weakness and a flaw, diminishes the business of politics and narrows its horizons. Worse, there is a potential arrogance in it: if there is no ideology, if there is only one truth to be arrived at by painstaking, inclusive, consensual deliberation, then anyone who rejects that “truth” is an enemy of the people. We cannot have that.

The prime minister is engaged in a political exercise and he should attract no blame for that. He must distinguish himself from the administration which went before, and he is painting himself as “the grown-up in the room”. But it is an exercise and it is a falsehood. Starmer may have buried it deep out of public sight, but he must have an ideological or principled view of the world. I sincerely hope he does, otherwise he should not be in senior public office. It is a vision which he has the means to pursue for the moment. But no-one who is active in politics should feel ashamed of articulating a philosophy and saying clearly what they believe. If we don’t do that, we tear the heart out of democracy and make the process an empty struggle. Doctrine, for lack of a better word, is good. Doctrine is right. Doctrine works. Let us stand up in its defence.

Excellent.