I'm not a journalist, and let me tell you why

Even though I write a lot for newspapers, there are different disciplines involved in producing content: mine is different from what journalists do, but we all have our place

I’m not a journalist. And let me explain why that matters.

Being asked what you do for a living is an absolutely standard part of social existence. When two strangers are forced together by circumstance, it’s an inquiry which guarantees at least a few conversational rallies, it isn’t regarded as too personal or potentially offensive and most people have a ready answer. Of course it’s an easier one to answer for some people than others: “I’m a police officer” or “I teach English” are intelligible to any enquirer, they have potential supplementary information if it’s required, and one can relate them to the reciprocal response.

I find it a little more challenging, not merely because of ingrained diffidence and awkwardness. In the old days, “I work in the House of Commons” was too imprecise, requiring clarification which I was always aware had not been sought, and very few people know to any extent—nor is there any reason they should—what a clerk in the House of Commons does. So I became all too familiar with the facial expression on others which said, eloquently, “I wish I’d never started this conversation” as I began explaining the select committee system or what distinguishes a private Member’s bill from any other kind of legislation.

These days, with what is, I hope, increasing fluency, I tend to respond “Well, I’m a writer, really”. It’s not the most emphatic or confident assertion, and it carries the whiff of qualification because I write several different sorts of content, in different contexts, I write fiction and non-fiction, and there are other things I do like consulting and networking and advising on all sorts of issues. At the moment—with the exception of the at-least-two books I’m supposed to be writing—my most pressing and visible work is for newspapers and magazines, so why, you may ask, bringing us unwittingly but according to my dastardly plan back to my original question, don’t I say I’m a journalist?

It is a long time since I first has a byline in a newspaper. A very long time, as it happens: Monday 2 April 1984. I was six years old, I won a competition in the Sunderland Echo run by their Young Reporters’ Club, and my submission to the Under-12 category, a straightforward tale of a visit to Tynemouth Priory, was published under the headline “Adventures at the old abbey”. (I will have to shoulder the burden of responsibility for inaccurately tagging the Benedictine community as an “abbey” rather than a “priory”, but, in my defence, I was only six.)

My regular career in print, however, really dates from March 2019, when the estimable Matt Chorley asked me to write a piece for The Times’s Red Box column. We were deep in the Brexit trenches, and Theresa May, by then in her last few months as prime minister, intended to offer the House of Commons (but really the parliamentary Conservative Party) a menu of options for a withdrawal scenario, which process was dubbed “indicative votes”. Having been a clerk in the Commons for more than a decade, I knew in my bones this was a disastrous idea, was incompatible with the very working of the House and would do nothing to resolve the prime minister’s political difficulties. I tweeted to that effect, and Matt read the tweet and asked me to expand for the coming Monday’s Red Box, which I was delighted to do.

Since then, I have managed to carve out a role as a more-or-less regular commentator on parliament, the Conservative Party and politics more generally, which has seen me settle at my keyboard for The Daily Telegraph, The Scotsman, The i Newspaper and, most regularly, City AM, for whom I have written a weekly column since the summer of 2019. I have also contributed to all sorts of other publications, and those who wish to become super-fans can find a collected list of my work here. As a paid contributor to newspapers and magazines in print as well as on the internet, then, surely I can say I’m a journalist?

Well, no. I’m not. I don’t have the training, I’m not sure I have the instincts or flair of good journalists, and I don’t do the same sort of work as journalists do. I avoid the term not only because it is misleading, but also because I don’t want to misappropriate a label which belongs to a demanding job which some people do really well. I’m a commentator, I write op-ed or opinion pieces, and they are a long-established and respectable part of a newspaper but they are not reportage.

(If you are interested and don’t already know this, comment pieces are referred to as “op-eds” because they first appeared on the page opposite the newspaper’s editorial. The New York Times’s John B. Oakes pioneered an op-ed page on 21 September 1970, writing “We hope that a contribution may be made toward stimulating new thought and provoking new discussion on public problems”. The first example, however, may have been the creation of Herbert Bayard Swope, editor of The New York Evening World, in 1921, of which innovation he noted:

It occurred to me that nothing is more interesting than opinion when opinion is interesting, so I devised a method of cleaning off the page opposite the editorial, which became the most important in America... and thereon I decided to print opinions, ignoring facts.

Swope was an epigrammatic, swashbuckling Missourian who had already won a Pulitzer Prize in 1917 and moved in society circles sufficiently elevated that rumours spread he was an inspiration for elements of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. But he at least deserves acknowledgement by the non-existent guild of professional opinion-possessors. I should found that.)

In my view, and this is why I shy away from the tag, a journalist is principally the discoverer, collator and presenter of facts. For an authoritative definition, we could do worse than go to City University’s collection of MA courses in journalism, one of the most prestigious institutions for those who want to be professional hacks:

As a journalist you will work with stories. It will be your job to find stories, package them in a certain format and communicate them to an audience through a variety of media. These may include television, radio, print or online.

That will do as a workable summation, and it captures many of the things I do not do. This is not simply to denigrate myself: I can produce 600 words, or 800, or 1,000, as required, on a subject of current interest, combining news, facts, analysis and opinion, I can do it with considerable speed, and—because why should I deny it?—I do so with a grace and elegance which seems to please enough people for editors to give me repeat business. Not all journalists could do this, though some can, in the same way that I cannot do what they do. So my avoidance of the word “journalist” is not so much about belittling myself as preferring a degree of precision when talking about what people do.

This is in my mind because earlier I watched Alison Millar’s 2022 documentary Lyra, a biography of the young Northern Irish journalist Lyra McKee who was murdered in the Creggan area of Londonderry in April 2019 by members of the New IRA. It is a poignant film, with the inevitability of its ending hovering above it, but for me, one of the greatest tragedies of the whole affair was the senselessness: the New IRA is a small, nihilistic splinter group of Republican terrorists, potent enough to try to murder DCI John Caldwell of the Police Service of Northern Ireland in February 2023, but numbering only a few hundred people at most; and, according to their own statement, they had not intended to murder Lyra and offered an apology to her family and her fiancée, Sara Canning. She was the first journalist to be killed in the UK since 2001, and, for all that some of her journalistic work had raised the hackles of those whom she probed, she was, in the end, in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I didn’t know Lyra but I know people who did, and she was highly rated as an investigative journalist, recognised by Forbes as one of their “30 Under 30” in the media in 2016. She had published a book about the murder of the Rev Robert Bradford MP in 1981, Angels with Blue Faces, in 2019 and signed a two-book deal with Faber and Faber. The film makes it clear that she was an unusually ambitious, determined and driven young woman who had long wanted to be a journalist, and was clearly a considerable and fearless talent. None of this, of course, makes her death more tragic in the long run than that of any other victim of the Troubles, but it did make me think again about the idea of journalism, or reporting, in its stricter sense; so too had some interviews I’d watched on YouTube with the late Christopher Hitchens, whom I admire enormously despite the fact that we share few political views. Moreover, one of Hitchens’s great heroes was George Orwell, who, in addition to being a supremely gifted novelist and polemicist, was a first-rate journalist: many rate his Homage to Catalonia as the best description of the Spanish Civil War, while The Road to Wigan Pier is a savage exposure of poverty in the industrial north of England in the 1930s.

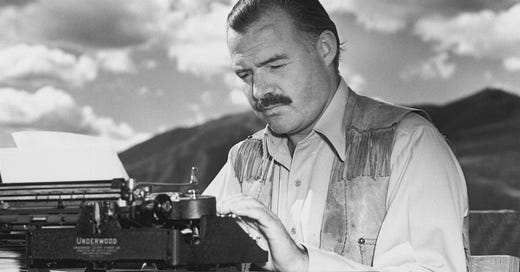

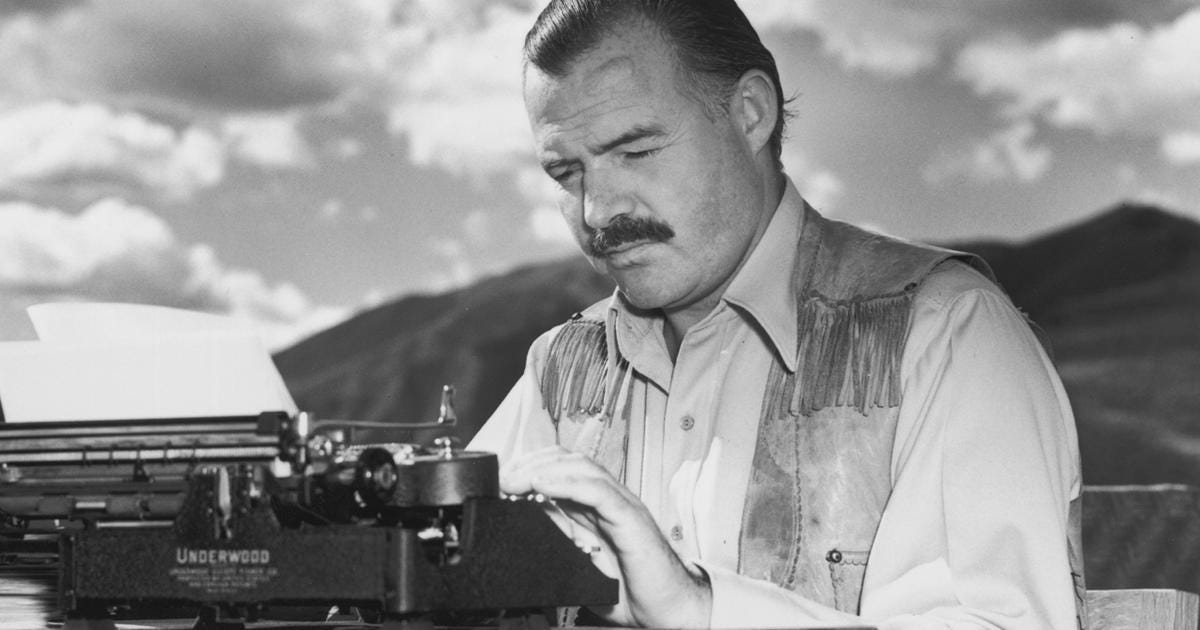

Journalism of the Orwell or McKee school will always have a glamour and a frisson of danger (tragically relevant in Lyra’s case) that sitting at a desk and having an opinion will never have. And that is as it should be. Journalists at their best can be heroic figures, from Hemingway in France in 1944 (the story was bruited that he had virtually single-handedly liberated Paris and arrived at the Ritz Hotel to drink champagne in vast quantities) to the late Marie Colvin, already one-eyed after a grenade attack in Sri Lanka but laughing in the face of death until the end in Homs in 2012. Let’s put it this way: the divine Rosamund Pike portrayed Colvin in 2018’s A Private War, but I am still waiting for the star-studded biopic of Owen Jones.

I wouldn’t for a moment suggest that journalists, unlike columnists, have no care for style or language. Sir Max Hastings marched and yomped with the British soldiers in the Falklands in 1982, and was with the first units to enter Port Stanley, but is a prolific and superb author and columnist; John Cole was a superb political editor for the BBC and knew Westminster inside out, but his style, enthusiasm and accent forged an extraordinary connection with the viewer; and Gillian Tett was Journalist of the Year in 2009 for her work at The Financial Times, had already picked up a doctorate in social anthropology from Clare College, Cambridge, and went on to write the acclaimed Anthro-Vision: A New Way to See in Life and Business in 2021.

I hope that explains a little bit about what I do, and why I differentiate myself from journalists and journalism. At the moment, I’ll take “columnist”, as I don’t think I’m quite prickly enough to be a polemicist (but give me time). But it is why I hesitate slightly when people ask me what it is I do.