I'm just the chief whip. I keep the troops in order.

Last night BBC4 repeated the 1990 TV classic House of Cards, which sees a dark and devious chief whip dispose of his rivals and become PM; it is, of course, fiction

One of the most enduring examples of British political drama was the BBC’s House of Cards, which was screened between 18 November and 9 December 1990. Eagle-eyed readers will notice that between those dates, on 28 November, Margaret Thatcher resigned the premiership after more than 11 years after losing the support of her parliamentary party. Given that the television series began with the (then theoretical) departure of the first female prime minister, it gave the drama an extraordinary, almost prophetic piquancy.

If anyone reading has not seen House of Cards, or thinks that Netflix series starring Kevin Spacey is an original concept, they should stop now and watch the BBC version immediately. It is that good. Based on a novel by Michael Dobbs, formerly the Conservative Party chief of staff, it was written after the author had a catastrophic falling-out with Thatcher just before the 1987 election and escaped for a holiday to Malta. He began by writing the letters “FU” and a pair of raised fingers on a pad of paper, but his initial intention was not to write a novel.

None of this was planned. It was all a bit of a joke, an accident. I had no intention of being a writer, or even finishing the book. It was just a holiday distraction.

Once he began, though, the words poured out. It was not, he insisted, a “book of revenge” but he based it on everything he had witnessed in politics, with the addition of Shakespearean motifs and plot devices. It was published in July 1989 and, with its two sequels, To Play The King and The Final Cut, went on to sell nearly 1.5 million copies worldwide. The BBC quickly snapped up the television rights and Andrew Davies, now a legendary screenwriter, was brought on board for the adaptation (and went on to win an Emmy for his troubles). Everything went right: the script was sharp and fast-paced, the timing was immaculate, and a superb cast was assembled. The young Susannah Harker was perfect as idealistic journalist Mattie Storin, drama stalwarts like David Lyon, Malcolm Tierney and Colin Jeavons filled out the senior ranks of the government, and to play the lead role of Francis Urquhart the producers turned to experienced classical actor Ian Richardson.

Richardson’s performance made a superior political drama into iconic television. He was 54 when the series was made, and had needed no persuasion to accept the part. Landmark television was no novelty to him. He had portrayed senior SIS officer Bill Haydon in 1979’s John le Carré adaptation Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy; but his best work had been on the stage. Nevertheless, Richardson could tell quality.

From the moment I read the first scripts, I felt that not only was it the biggest acting opportunity to come my way since my Shakespeare days, but probably was going to be something rather special on the box.

He was right, and it was in no small way down to him. Urquhart was a rather stiff, reserved Scottish aristocrat, the younger son of an earl, who rose to the position of chief whip through diligence rather than brilliance. He was widely respected rather than liked, and a highly effective party disciplinarian. Addressing the camera directly in the first episode, he explains his role: “I’m the Chief Whip. Merely a functionary. I keep the troops in line. I put a bit of stick about. I make ’em jump.”

Richardson gave the role the appropriate formality—by 1990, Establishment figures like Urquhart were beginning to look old-fashioned even in the Conservative Party, and the chief whip’s three-piece suits, brown trilby and camel coat caught the eye—but his stage experience also allowed him to unleash a gloriously feline and sinister manner when breaking the fourth wall. His clipped, clear diction was perfect for the role. Richardson was born in Edinburgh and educated at George Heriot’s, an independent school in the city, and grew up with the accent of his native land, but as he showed promise in acting a director advised him that a working-class Edinburgh inflection would hold him back. Elocution lessons gave him razor-sharp received pronunciation, perfect for the rapid-fire diction of classical theatre but also absolutely in tune with the character of Urquhart.

Assuming you have already seen or read House of Cards, you know the plot. The important factor is that the government chief whip (who holds the formal title of parliamentary secretary to the Treasury to attract a ministerial salary) is passed over for promotion by Thatcher’s successor in Downing Street, Henry Collingridge, and begins to plot an elaborate scheme of revenge which will bring down the new prime minister, eliminate any likely successors and see Urquhart himself elected as leader of the party. Dobbs would be the first to admit that, while there are many authentic touches to his story, some is, inevitably in fiction, exaggerated or implausible. One of the most unlikely ideas is that of the chief whip going to 10 Downing Street.

There have been chief whips since around 1830, as the formal political party system began to crystallise. Some have achieved a degree of fame, like Willie Whitelaw, later Margaret Thatcher’s deputy, or the recently resigned Gavin Williamson; others would baffle even dedicated political geeks, like Denis le Marchant or Aretas Akers-Douglas. Sometimes chief whips have gone on to cabinet office, even to one of the great offices of state, but, in nearly 200 years, only one holder of the office has “done an Urquhart” and become prime minister: Edward Heath.

Heath was appointed chief whip in 1955 by Sir Anthony Eden. He was under 40, and had been in the Commons for less than five years, but was regarded as a particularly promising member of the fêted 1950 intake. Decades later, a journalist would remark that “Of all government jobs, this requires firmness and fairness allied to tact and patience and Heath’s ascent seems baffling in hindsight”. Eden may have turned to him largely because he was already deputy chief whip, but in his four years in post, from 1955 to 1959, he performed well, holding the parliamentary party together through the trauma of the Suez crisis and managing the slightly surprising elevation of Harold Macmillan to the premiership in 1957. However, Heath did not become prime minister in 1970 because of his service as chief whip; and indeed he was displaced as party leader in 1975 not least because of his poor management of his colleagues. Much more important was the fact that he had moved on to a respectable cabinet career after 1959.

If Heath is the exception rather than the rule, there is one more curious observation. When Thatcher reshuffled her government after her third election victory in 1987, her first choice for chief whip was an able but unspectacular minister of state at the DHSS, John Major. The chancellor of the exchequer, Nigel Lawson, also wanted Major’s services in the Treasury as chief secretary, the second senior ministerial role, and persuaded Thatcher to change her mind (no mean feat). Instead she chose as chief whip David Waddington, an unflashy but able QC who thought he was likely to be appointed solicitor general. The decision was a very close on. When Waddington arrived at his new office in 12 Downing Street, he found notes left by his predecessor John Wakeham which set out ministerial appointments including Major’s as chief whip and his own as the junior law officer.

Nigel Lawson, in his 1992 memoirs The View from No. 11, remarks in a footnote that if Major had been made chief whip in 1987, it would have been very unlikely that he would have become prime minister just three years later, “pace Mr Michael Dobbs”. This direct reference to Francis Urquhart’s career trajectory underlines how implausible that plot device was compared to the reality of politics. Even if Major had been promoted to cabinet in 1989 or 1990, there is almost now way he would have been in the powerful position he actually was, as chancellor of the exchequer, to be Thatcher’s successor. This is no reflection on Major himself—he may well have been an effective business manager, with a sharp brain and a pleasant manner—but it highlights the peculiar status of the chief whip: the incumbent attends cabinet, but is not (normally) a full member, and wields extensive power as a disciplinarian and organiser but has little influence over policy or executive action.

The appearance on BBC2 last night of the brilliantly realised Urquhart has prompted me to look at a few previous chief whips. Last month I wrote an essay on the Conservative Party’s whipping over the last decades and suggested that many of the chief whips have performed poorly, so instead I will look here at one of the outstanding and legendary chiefs of the last century. I will not dwell too much on the role and duties of the chief whip. Readers will have a reasonable idea, I have touched on the subject before and a full exploration would be a whole essay on its own.

I will observe, though, that there are broadly two types of whip (at all grades): those who serve in the role because it is a useful part of a ministerial career which adds experiences politicians will not find elsewhere; and those who are naturally gifted at the strange, coercive persuasion and pastoral care which the whips’ offices carry out. Many ministers will pass through the office over the spread of a career, and, simply to look at the current cabinet, Ben Wallace, the defence secretary, spent a year as a whip, while the Welsh secretary, David T.C. Davies, spent twice that time as a whip. On the other hand, the former chief whip Patrick McLoughlin was clearly born to the position, spending 17 years in the Conservative whips’ office, as a government whip (1995-97), opposition whip (1997-98), opposition deputy chief whip (1998-2005), opposition chief whip (2005-10) and finally government chief whip (2010-12). He has spoken of the immense variety of being a whip, but also the amount you learn about the parliamentary party. Tristan Garel-Jones, a whip from 1986 to 1990, the last year as deputy chief, was also regarded as a rather complicated, Machiavellian figure who thrived in that role.

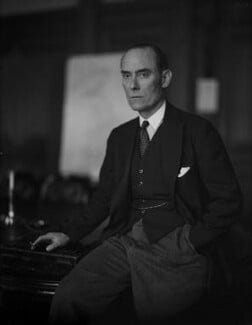

The longest-serving government chief whip since the post was established was Captain David Margesson, who held the office from 1931 to 1940, serving under four prime ministers. Conservative MP for Rugby (having earlier sat briefly for Upton), he took his seat for the second time after the general election of October 1924. He came from an upper-class family in Worcestershire and was educated at Harrow and Magdalene College, Cambridge, though he left without completing his degree to explore opportunities in the US with the reckless optimism that young, well-born men could afford in the days just before the First World War. Amusingly for the many enemies he would later earn, he spent some time walking the floors of a department store in Chicago.

He served on the western front with the 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s Own), rising to the rank of captain which would remain attached to him throughout his political career (it even prefixed his name in House of Commons papers), and winning the Military Cross. By 1922, he had attracted the patronage of senior Conservative minister Lord Lee of Fareham, leading him to his blink-and-you-miss-it time as MP for Upton between 1922 and 1923. He was, however, selected to second the Loyal Address, the Commons’ formal response to the King’s speech, a prestigious honour always given to a new backbencher.

Margesson was fortunate to return to the Commons so quickly in 1924. He was 34 years old, had a secure majority over the Liberal Party in his constituency and was supporting a government which had won by a landslide: Stanley Baldwin’s Conservatives had won 412 seats out of a total of 615. Straightaway he was named an assistant whip, then rapidly promoted to lord commissioner of the Treasury, the office held by the senior rank-and-file whips. His military manner and experience as his regiment’s adjutant during the war recommended him for the duties of party management.

There was not an overwhelming challenge in keeping the parliamentary troops in order between 1924 and 1929. The government had a huge majority, the opposition was split between the Labour Party, bruised by its helter-skelter first taste of office in 1924, and the Liberals, exhausted by internecine struggle and seeing their natural constituency slip away, and the emollient Baldwin was not a man to polarise his backbenchers. The defining feature of the period was the General Strike of 1926. The government handled it deftly; Baldwin used the provisions of the Emergency Powers Act 1920 to deploy military personnel and volunteers and the strike collapsed in nine days.

In the summer of 1931, the second Labour government collapsed after failing to agree on measures to address the financial crisis and after the intervention of George V a National coalition government was formed consisting of the Conservative Party; those Labour MPs who continued to support the prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald; and the Liberals, who were a living embodiment of the motto tria iuncta in uno, being split between the official Liberals under Sir Herbert Samuel, Sir John Simon’s Liberal National group which accepted the Conservatives’ preferred policy of protectionism and a small group of independent Liberals who still adhered to David Lloyd George and his financial party machine. Margesson was reappointed as a lord commissioner of the Treasury when the new administration was constructed in August.

The coalition went to the polls in October 1931. The idea of cooperating to address a state of emergency appealed to the voters, and the governing parties collectively won a shattering victory: the Conservatives won 470 seats, the Liberals 32, the Liberal Nationals 35 and MacDonald’s National Labour 13 and four other MPs supporting the government. That gave the administration a strength of 554, an unimaginably powerful position, while the Labour Party, having expelled MacDonald and left office, could muster only 52 MPs, but were the official opposition.

When jobs were handed out, Margesson, only 41, was named Conservative chief whip and parliamentary secretary to the Treasury, his predecessor promoted to the cabinet. The task ahead of him was both easy and sensitive: on the one hand, there was to all intents and purposes no opposition, and it was inconceivable that the government would be defeated in a division. On the other hand, he was the business manager for a four-party coalition (two parties of which were different flavours of Liberal), juggling up to four different opinions on any given policy, which added a degree of complication to keeping backbenchers in line. It was, however, undoubtedly a senior role, and Baldwin would write to him that “there is no relationship between men so close as that of a prime minister and his chief whip”.

The style of the Conservative whips’ office in the 1930s was strict and formal. Many MPs, of course, had served in the Great War, so a sort of military discipline came easily to them, while many had been educated at public school, which produced the same familiarity with obedience and authority. This seemed to coincide with Margesson’s natural inclination, and it was felt that, for all the government’s titanic majority, the party management was run fiercely and without much mercy. He quickly became a formidable and feared figure, well-dressed and, depending on your witness, “florid” or “a lean, darkly handsome man”.

If Margesson was strict, he was not unbending, and his management of the coalition was dextrous. In March 1932, he opened negotiations with Sir Oswald Mosley to try to tempt the erratic baronet to join the National coalition. Today we think of Mosley simply as a fascist, marching at the head of his Blackshirts, but at the time the judgement was not so obvious. After his switch to Labour in 1924, he had become an energetic and creative thinker, and when the party returned to office in 1929, he was made chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster and tasked with finding solutions to the unemployment crisis. Frustrated by his colleagues, he published his ideas as the “Mosley Memorandum” which advised high tariffs, nationalisation, a higher school leaving age and a major programme of public works, all organised by a National Planning Council. He resigned from the government in May 1930, but his memorandum was praised by John Maynard Keynes as “a very able document and illuminating”.

Always restless, Mosley quit the Labour Party in February 1931. The following day he established the New Party, initially with six MPs: Mosley himself, his wife Lady Cynthia Mosley, the Conservative leader’s son Oliver Baldwin, W.J. Brown, Robert Forgan and John Strachey. They received funding of £50,000 from industrialist Lord Nuffield (about £4 million in today’s money), but after the 1931 general election all had left or been defeated. The New Party did not have long left—it folded itself into the new British Union of Fascists in October 1932—but in that narrow window, Mosley and the energy of his ideas were a prize worth having. Margesson knew that Mosley had considerable appeal to the young, and he was also firmly anti-communist. Labour was also courting him. But Mosley was now heading towards the embrace of fascism and the descent into ignominy.

An article by Peter Howard in The Sunday Express in 1935 gives us an insight into Margesson’s style as chief whip. He gathered the new MPs together to impart some advice to them, and the atmosphere was, Howard said, “just like school again”. Margesson was the headmaster, and he talked while his charges listened. He advised them not to wear top hats—this was a custom on its very last legs in the chamber—and then told them that they should make their maiden speeches quickly. If they did not, he warned, journalists like Howard would take notice and target them for abuse in print.

The main ideological rift which Margesson had to manage was over the response to growing German rearmament and reassertion of national power. One of the first rebels to draw attention to the potential danger of German policy was Winston Churchill: not, as now, the saviour of the nation, but then a figure regarded with suspicion, with a patchy record as chancellor in the 1920s and unfashionably hardline views on India. This inevitably made it more difficult for Churchill to be taken seriously, and Margesson’s iron discipline kept him relatively isolated. There was no suggestion that he might be offered a position in the National government, and he reinforced his own image as a crank, dismissing Indians as “humble primitives” and Mahatma Gandhi as “a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as fakir of a type well known in the East”. When the former viceroy, Viscount Halifax, suggested his views were out of date and he should become familiar with Indian opinion, Churchill was dismissive. “I am quite satisfied with my views of India. I don’t want them disturbed by any bloody Indian.”

Churchill was not quite a lone voice on the backbenches, but those who did hold him in esteem were a motley crew. The Member for Paddington North, a shady young Irishman called Brendan Bracken, was described by Baldwin as Churchill’s “faithful chela”, but was an outlier in the Conservative Party. His other cronies, like newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook and the opinionated professor of experimental philosophy at Oxford, Frederick Lindemann, also reflected little glory. And the man himself further alienated colleagues with his wholeheartedly support for the Prince of Wales in his romantic pursuit of Wallis Simpson.

Margesson also dealt with another group of anti-appeasers, the young and largely homosexual MPs he referred to dismissively and meaningfully as the “Glamour Boys”. They were not directly allied with Churchill, though they were closer to Anthony Eden, and included Members like Victor Cazalet, Robert Bernays and Ronald Cartland. The heavy innuendo that many of these critics of the government were gay was deployed repeatedly by Margesson and his whips, as well as being promoted in the press.

By the time the final crisis came in Europe, Margesson had the government’s parliamentary troops under reasonable control. He was strict but not universally bullying. Harold Macmillan, rebellious of spirit in the 1930s, always found the chief whip charming and friendly, and Margesson was civil to the administration’s critics, even to Churchill. After the accession to the premiership of Neville Chamberlain in 1937, it was true that he was focused overwhelmingly on loyalty, and there was a general feeling in the Commons that his influence on ministerial appointments was in favour of reliable and compliant men. Joseph Kennedy, the US ambassador to London from 1938 to 1940, compared him to a Tammany Hall boss, which was a shrewd observation.

The chief whip was a loyal lieutenant to his prime ministers, especially to Chamberlain, to whom he grew very close. And Chamberlain needed that loyalty and support. It is easy to forget what a shock to the political system he was when he finally became prime minister in 1937. The MacDonald and Baldwin years had passed in a more gentle atmosphere: the former was ageing and ill, increasingly a figurehead after 1933, and Baldwin, when he began his third stint in Downing Street in 1935, was in his late 60s and unlikely to show more verve and spirit than he had done as a younger leader. Chamberlain may have been 68 when he finally achieved the office which had eluded his father and his half-brother, and many thought him a stopgap until after the next election (due by 1940), but he possessed formidable energy. He also brought a harder edge to the conduct of business: he felt his predecessors had been too lenient on inadequate colleagues, and sacked the president of the Board of Trade, Walter Runciman, whom he felt to be lazy.

If others felt Chamberlain was a stopgap, no-one had told the prime minister, and he quickly ordered departmental ministers to prepare two-year plans which could be integrated into a comprehensive legislative programme to take the government to the brink of the next election. Margesson said of Chamberlain:

He engendered personal dislike among his opponents to an extent almost unbelievable… I believe the reason was that his cold intellect was too much for them, he beat them up in an argument and debunked their catchphrases.

This came as a jolt to the opposition leaders, but his businesslike approach suited the chief whip well enough. As opposition to the government’s foreign policy continued to grow, it became an increasing source of anxiety to Margesson. He could still rely on broad public support for keeping the UK out of war—one of his gifts was an ability to read the mood of the electorate—but each crisis made the situation more difficult.

When appeasement finally failed in 1939, and conflict with Germany became inevitable, Margesson was shrewd enough to see that he had to deliver hard truths to the prime minister. The three days which led from Germany’s invasion of Poland on 1 September to the UK’s declaration of war on 3 September were the height of febrility in parliament. When the Commons met on the evening of 1 September, Chamberlain was grave but firm, talking of “action rather than speech”, and all sides seemed in broad agreement. But the mood soured the next day. The chancellor, Sir John Simon, was supposed to make a statement to the House but was recalled to a cabinet meeting, and Chamberlain’s own appearance on the front bench was delayed substantially. When he arrived at around 7.45 pm, Members were grim, irritated and, in many cases, drunk.

The prime minister’s statement was poor. He made vague references to considering, with France, drafting an ultimatum, but was so short on details that Members became suspicious. Harry Crookshank, the financial secretary to the Treasury, who had almost resigned over the Munich agreement, wrote in his diary that Chamberlain’s speech “left the House aghast. It was very badly worded and the obvious inference was vacillation or dirty work”. Matters worsened when Arthur Greenwood, the deputy leader of the Labour Party (Clement Attlee was ill) stood up to respond for the opposition. Before he could speak, Leo Amery, a long-serving Conservative MP and former cabinet minister, shouted “Speak for England”. Greenwood lamented the delay in responding to Germany’s aggression and there followed a succession of speakers on the same theme. Chamberlain was saved by the speaker accepting a motion for the adjournment and the House rising at 8.09 pm, but he and Margesson knew that they had stared at the collapse of the government; if a division had been called, it would have gone against them. In the words of one MP, Chamberlain was “white as a sheet” and Margesson was “purple in the face”. The chief whip was now convinced that a declaration of war against Germany had to come the following day, or the government was finished. He remarked to Henry Channon, MP for Southend, “It must be war, Chips, old boy. There’s no other way out”.

The cabinet had come to the same view. After the House had adjourned, several ministers met in Sir John Simon’s Commons office and drafted a letter which demanded that any ultimatum issued to Germany could not extend beyond noon the following day. The cabinet met just before midnight and the arrangements were agreed for the UK’s ambassador in Berlin, Sir Nevile Henderson, to present such an ultimatum. Margesson was right. There was no other way out.

There were organisational tasks for Margesson to attend to. The cabinet needed to be modified, and, in particular, it was time (at last) to bring Churchill back into the fold. Margesson had in fact been taking soundings with Conservative backbenchers since the summer about their likely reaction to Churchill being given a ministerial role. Now that there was to be a war, it was essential to broaden the base of the government to reflect the new reality. However, the Labour Party and the official Liberals (who had gone into opposition in 1933) refused at this point to join the coalition. So Chamberlain brought in Churchill as first lord of the Admiralty and Eden as secretary of state for the Dominions, thereby co-opting the government’s two most powerful pre-war critics. If some backbenchers were uneasy about Churchill’s return to the office he had last held from 1911 to 1915, the Senior Service was less reticent, and the Board of Admiralty sent a signal to the whole fleet which read simply “Winston’s back”.

Margesson also had an informal conversation with Labour’s Arthur Greenwood about a wartime truce for by-elections, to which the chief whips of the three major parties agreed on 8 September. This effectively put to bed electoral politics for the duration of the conflict, as would the passing of five Prolongation of Parliament Acts from 1940 to 1944, in order to delay the general election which had been due in November 1940 until hostilities ended.

After the tension of the declaration of war there was an extended period in which there was almost no military action in the West. Poland, attacked on both sides by not only Nazi Germany but her temporary ally the USSR, collapsed on 6 October, though she never formally surrendered. But the winter of 1939/40 became known as the “Phoney War”. When action was finally taken in April 1940, with Churchill harking back to the spirit of the Dardanelles Campaign by seeking to open a new front with Germany, the Royal Navy undertook Operation Wilfred, to mine the waters around Norway and in particular to disrupt the transport of iron ore from Narvik, in the high north of Norway, to the German industrial heartlands. The German armed forces were ahead of them, however, and the day afterwards, with 120,000 men, they occupied Denmark and invaded Norway.

Taken by surprise, the Allies assembled a British/French/Polish expeditionary force of 38,000 to counter the Germans in Norway. They made little headway, and by the end of April they had withdrawn from south and central Norway. Was history repeating itself? Churchill, restored to the Admiralty, had proposed a daring and counter-intuitive measure to disrupt the flow of the war, but the enemy had caught them off-balance and it was slipping into failure. In Westminster, once again, serious questions were being asked about the national leadership.

On Tuesday 7 May, a two-day debate officially entitled “Conduct of the War” began. It was a debate on a motion for the adjournment for the Whitsun break, which allowed the House to discuss the issue in broad terms without having to vote on a substantive motion (the question was simply That this House do now adjourn). At 3.48 pm, Margesson rose to propose the question, and the debate opened with a speech by Chamberlain. He began in a rather flat manner, making an early tactical mistake, perhaps, in anticipating the criticisms Members might make of the government’s direction of the Norway campaign. “Ministers, of course, must be expected to be blamed for everything,” he complained rather peevishly. Hansard records that honourable Members responded by jeering “They missed the bus.”

This was a bad early sign. A month before, Chamberlain had confidently told a Conservative Party meeting that the German war machine had stalled, and that Hitler “had missed the bus”. Within a week, the Wehrmacht surged into Denmark and Norway. Now MPs were turning Chamberlain’s own phrase against him with withering scorn. The prime minister pressed on with his lacklustre defence of the campaign—it sounded rather more like a series of excuses—before saying that he was trying to be neither too optimistic nor too downcast. Again, MPs shouted “Hitler missed the bus!” and Chamberlain exacerbated the situation by repeating the phrase, to cries of “You said it!” He concluded by promising to make organisational changes where necessary and appealing to a sense of unity during the conflict.

As far as we in the Government are concerned, we are doing all we can to overtake the start which Germany has obtained during her long years of preparation. We are getting to-day the wholehearted co-operation of employers and workers; we want also to get the co-operation of hon. Members of all parties.

Chamberlain sat down having spoken for about an hour. He had certainly not improved the position of the government; arguably he had made things worse.

Clement Attlee, the Labour leader, opened for the opposition. Carefully and calmly, he asked a series of detailed questions about the government’s decision-making processes. But his real target was the organisation of the War Cabinet and the direction of military operations. Chamberlain was struggling, and had recently attempted to dampen down criticism by announcing that Churchill would henceforth chair not only the Admiralty board but the Chiefs of Staff Committee as well. It was a desperate ploy, and one which put him in danger of the fate which had befallen Asquith in 1916: promoting his rival to such an influential position and marginalising himself that it would raise the question of why he remained prime minister at all.

Attlee concluded by accusing government backbenchers of uncritical loyalty. They had lost their analytical skills, he argued, cowed into mere obedience and allowing Chamberlain to dominate them. Quite simply, they had not been tough enough.

I think it is a particular weakness of hon. Members on the benches opposite. They have seen failure after failure merely shifted along those benches, either lower down or further up. They have been content, week after week, with Ministers whom they knew were failures.

He even singled out Margesson as the author of this pitiful trend. Backbenchers “have allowed their loyalty to the Chief Whip to overcome their loyalty to the real needs of the country”. He concluded with a very serious charge, that major changes were needed. Reading between the lines, it was easy to believe that his real meaning was that Chamberlain must go. “I say that there is a widespread feeling in this country, not that we shall lose the war, that we will win the war, but that to win the war, we want different people at the helm from those who have led us into it”.

Brigadier-General Sir Henry Croft, MP for Bournemouth and something of a reactionary, gave an adequate defence of the government. He was sharply countered by Colonel Josiah Wedgwood, scion of the pottery manufacturer, MP for Newcastle-under-Lyme and a former Labour cabinet minister, who condemned “facile optimism, that saps the morale of the whole country”. Like Attlee, he talked about making changes to the government, and again like Attlee, he made a thinly veiled point: Chamberlain was now an obstacle to success.

I hope we shall get on that Bench a Government which can take this war seriously instead of being prepared to go on in the old style and thinking this is a replica of 1914. We are living in a new world and this is a new war, the end of which may be the utter destruction of the British people. Whatever our parties everyone would sacrifice his life, position and everything else in order to achieve out salvation.

When Wedgwood had concluded, the debate took a dramatic turn. At 7.09 pm, the Conservative MP for Portsmouth North, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, caught the speaker’s eye. He could hardly have failed to do so: he was dressed in full naval uniform, with six rows of medals and the star of the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. He brushed off Wedgwood’s attack and said that he was there as a representative of his service. “I wish to speak for some officers and men of the fighting, sea-going Navy who are very unhappy.”

Keyes may have dismissed Wedgwood, but he was not there to support the government. He told the House that he had implored ministers to place him in command of the Norway operation, while making repeated comparisons to the catastrophe of Gallipoli (where he had served). But his criticisms excepted one person, Churchill.

I have great admiration and affection for my right hon. Friend the First Lord of the Admiralty. I am longing to see proper use made of his great abilities. I cannot believe it will be done under the existing system. The war cannot be won by committees, and those responsible for its prosecution must have full power to act, without the delays of conferences.

Here was the same charge again: the machinery of government was not performing properly, it must be reconstructed and—that heavy hint again—Chamberlain’s continued presence in office was part of the problem. The solution which Keyes all but spelled out was that Churchill should take over strategic direction of the war.

At that time, he had many enemies, who discredited his judgment and welcomed his downfall. Now, however, he has the confidence of the War Cabinet, as was made abundantly clear to me when I tried to interest them in my project; he has the confidence of the Navy, and indeed of the whole country, which is looking to him to help to win the war. I am certain that to-morrow night he will deliver a very fierce counter attack on me, because he is always loyal to his friends and his colleagues, but having done that, I do hope he will accept my view, which, after all, is based on experience, precedent and achievement. I beg him to steel his heart and take the steps that are necessary to ensure that more vigorous Naval action in Norway is no longer delayed. If he does, he will have the Navy wholeheartedly behind him.

Keyes’s speech could hardly have been better for Churchill, nor worse for Chamberlain. In many ways, it was a masterpiece: he had analysed the problems, laid the blame for the Norway debacle at the door of the prime minister, anticipated Churchill’s defence of the government for form’s sake, and invoked the spirit of the Royal Navy to pledge his support for a Churchill premiership.

Next up was Lewis Jones, Liberal National MP for Swansea West. He spoke of his shock at the sharpness of the criticism of Chamberlain and reiterated Chamberlain’s appeal for unity. “I think the country is entitled to say to the right hon. Gentleman [Lloyd George] and to the Leaders of the Opposition that it is time they ceased slinging their political arrows when the country is in such desperate straits.” Jones pointed out that the opposition parties had been offered a chance to join the government in September 1939 but had refused.

He was followed by Captain Frederick Bellenger (Lab, Bassetlaw), who noted that he had been called up from the Army Reserve the previous October. His target was Chamberlain, of course, and he suggested that the opposition parties would have no part in a broader coalition while Chamberlain remained in the premiership. “We know only too well that the Prime Minister can be a very obstinate man, and if his proposal is that certain Members of the Opposition should take office under him, I for one would say that it would be impossible.” The logical conclusion, therefore, was that Chamberlain must go before Labour would come in.

Just after 8.00 pm, the speaker called Leo Amery, an Indian-born schoolmate of Churchill’s who represented Birmingham Sparkbrook as a Liberal Unionist then a Conservative. Ferociously intellectual but not a sparkling orator, he had been first lord of the Admiralty then colonial secretary under Baldwin, but had been left out of office when the National government was formed. He had spent the 1930s as a critic of appeasement and had condemned the Munich agreement. It was Amery, we may recall, who had shouted “Speak for England!” at Arthur Greenwood during the debate on joining the war the previous September. For the second time, his speech reached a level he would never again attain and had a genuine influence on the course of the debate.

Amery was contemptuous of Chamberlain’s opening speech. He declared that “the Prime Minister gave us a reasoned, argumentative case for our failure. It is always possible to do that after every failure”. That must have stung. Like the other attacks on the government, he condemned the current organisation and, by implication, Chamberlain’s leadership. “We cannot go on as we are. There must be a change. First and foremost, it must be a change in the system and structure of our governmental machine.” The government must expand to include the opposition parties.

Unlike the tacit references which had already been made, Amery made direct comparisons with the fall of Asquith in 1916. That trauma for the governing classes had demonstrated an indubitable argument, that a major war had to be directed by a small war cabinet unburdened by everyday departmental responsibilities.

We learned that in the last war. My right hon. Friend the Member for Carnarvon Boroughs [Lloyd George] earned the undying gratitude of the nation for the courage he showed in adopting what was then a new experiment. The experiment worked, and it helped to win the war. After the war years, the Committee of Imperial Defence laid it down as axiomatic that, while in a minor war you might go on with an ordinary Cabinet, helped perhaps by a War Committee, in a major war you must have a War Cabinet—meaning precisely the type of Cabinet that my right hon. Friend introduced then.

Amery stressed that the measures required were well known, and perhaps widely accepted. Yet they had not been adopted. Time was passing, and the country’s military situation was deteriorating. Germany was now largely in control of Denmark and Norway, and the UK had suffered a humiliating reverse. If everyone knew what to do, then. the government had to do it. Amery’s patience had run out, and he electrified the House with his final, desperate plea.

I have quoted certain words of Oliver Cromwell. I will quote certain other words. I do it with great reluctance, because I am speaking of those who are old friends and associates of mine, but they are words which, I think, are applicable to the present situation. This is what Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: ‘You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go.’

Members had greeted each of Amery’s attacks on the government with louder and louder cheers, and his dramatic peroration resulted in thunderous noises of approval. The mood had worsened and now, perhaps, had even changed. As TIME noted a week or two later, when the debate had begun, no-one seriously imagined that the danger to Chamberlain was potentially fatal. Now it was clear that his political life hung in the balance.

Commander Sir Archibald Southby, MP for Epsom and a Royal Navy veteran, now spoke in defence of the government. Perhaps unwittingly, though, he boiled down the debate to its essential elements: the tension between pressing for changes to the government to allow it to pursue the war more effectively, while remaining fundamentally loyal to the Chamberlain administration in principle. The exchanges in Parliament, as he put it:

will have served a useful purpose if it brings the people of this country and the Members of the House back to a unity of purpose in prosecuting the war to an ultimate successful conclusion. If there have to be changes in personnel, let us have them, but let us realise that to bring down the Government of this country by means of intrigue, from whatever part of the House it comes, would be to do a great disservice to the Allied cause which might well be irreparable.

The debate was concluded for the first day by the secretary of state for war, Oliver Stanley. A well regarded figure in the Conservative Party, he carried the weight of expectation as his father, the Earl of Derby, had run the War Office in the second part of the Great War (though not without criticism). He tried to rebut some of the charges made against the government while maintaining an emollient and engaged tone, battling against barbs from Attlee, Bellenger and Viscountess Astor, among others. He prayed in aid his own military service—he had been an officer in the Royal Field Artillery and had won the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre—and ended on a note which was rather pleading: “There are a thousand things that cannot be explained on the Floor of the House.” The debate ended at 11.30 pm, with another full day still to run.

The second day’s debate opened at 4.30 pm. That morning, Labour’s parliamentary executive had met to discuss the situation, and it was agreed that the discontent within the governing coalition was much more serious than anyone had realised. That being the case, Attlee proposed that they force a division at the close of business, to test the scale of a government rebellion. This changed the dynamic utterly. It had until now been a simple debate on the adjournment of the House, intended to encompass a general discussion of the conduct of the war. Dividing the House, even if the result would have no procedural effect, would not only enumerate the government’s detractors, but, by that token, would transform a general debate into what was effectively a motion of censure.

Herbert Morrison, MP for Hackney South and former leader of London County Council, opened for the opposition. He complained that Churchill, whom he called Chamberlain’s “principal witness”, would speak last of all in the debate, and revealed that the opposition had requested that the first lord of the Admiralty be called earlier, but to no effect. The partisan atmosphere was beginning to harden, gloves being removed. After rehearsing the case against the government as revealed and developed the previous day, he announced that the Labour Party would divide the House at the end of the debate, and upped the ante by trying to position the vote as one which Chamberlain had to win.

I ask hon. Members in all parts of the House to realise to the full the responsibility of the vote which they will give to-night, a vote which will, broadly, indicate whether they are content with the conduct of affairs or whether they are apprehensive about the conduct of affairs. I have little doubt about the feelings and the apprehensions of our fellow-countrymen outside.

This revelation brought the prime minister angrily to his feet (and must have come as an unpleasant shock to Margesson). He criticised the opposition for politicising the matter by seeking a division, but then made the atmosphere infinitely worse in that regard by effectively saying that Margesson and his team would whip their backbenchers into supporting the government.

I do not seek to evade criticism, but I say this to my friends in the House—and I have friends in the House. No Government can prosecute a war efficiently unless it has public and Parliamentary support. I accept the challenge. I welcome it indeed. At least we shall see who is with us and who is against us, and I call on my friends to support us in the Lobby to-night.

The use of the word “friends” went down badly, many Members feeling it was crassly emotional and manipulative. Perhaps the prime minister was thinking of the usage of “honourable friends” to describe his own side of the House, but it did not come across that way. Essentially Chamberlain was reducing what even his ministers had admitted were valid questions to be asked of the government to a crude appeal for support based on personal loyalty. It also seemed to confirm Margesson’s reputation as Chamberlain’s consigliere, brutally loyal to him personally in deploying the power of the whips’ office.

In fairness to Margesson, he would have been forgiven for feeling somewhat swindled. He had up until that point had an informal agreement with the Labour chief whip, Sir Charles Edwards, that the opposition would notify the government if it intended to press a question to a division. This was, admittedly, a gracious concession: the government’s majority was enormous, and surprise is one of the few weapons in the hands of a parliamentary opposition. Nevertheless, however gracious, it had been an agreement and it had been observed. For Margesson to learn now, on the floor of the House, that there would be a division, and an absolutely crucial one, in a few hours, was not in the spirit of the “usual channels”.

The government’s case was opened by Sir Samuel Hoare, the secretary of state for air. He had only been appointed a month before, but was in his third term at the Air Ministry. Nevertheless, his speech was weak, and he got badly muddled under questioning, at one point seeming to confuse or conflate the RAF with the Fleet Air Arm. Opposition Members seemed to scent blood, and began to bombard him with detailed technical interventions to which he struggled to respond adequately.

Then followed David Lloyd George. Prime minister during the previous world war, Lloyd George had remained in the House of Commons as his contemporaries had fallen away or ascended to the Lords, and was now 77 but remained active and, it would later transpire, ambitious. He had been ill when the National government was formed in 1931, and thereby missed out on an invitation to serve, but he still entertained some idea of being recalled to save the nation in its hour of need. He spoke of the need to be honest with the country about the strategic situation and framed his speech as requiring the departure of the prime minister.

Lloyd George and Chamberlain were old enemies. Although the Welshman had brought Chamberlain into his government as director-general of national service, their relationship was frosty. Chamberlain, resigning after a year, had vowed never to work with Lloyd George again, while Lloyd George could not help directing his punchy phrase-making towards Chamberlain. “Neville has a retail mind in a wholesale business,” he once remarked acidly of the man he also dubbed “a good lord mayor of Birmingham in a lean year”.

The Welshman was interrupted in his flow at one point by a remark the details of which Hansard does not record. But his response was revealing. “You will have to listen to it, either now or later on. Hitler does not hold himself answerable to the whips or the Patronage Secretary.” The patronage secretary was another name for the chief whip, so here was Lloyd George, directly referring to Margesson and his team. The mood was souring further. And it got worse as Lloyd George reached his peroration. He tried to exonerate Churchill from the worst of the government’s mistakes; when Churchill reassured the House that he took responsibility, Lloyd George chided him “The right hon. Gentleman must not allow himself to be converted into an air-raid shelter to keep the splinters from hitting his colleagues.”

It was clear which colleague he had in mind. He continued “The Prime Minister is not in a position to make his personality in this respect inseparable from the interests of the country.”

Chamberlain rose, furious. “What is the meaning of that observation? I have never represented that my personality—” He was drowned out by cries of “You did!” from MPs. “On the contrary, I took pains to say that personalities ought to have no place in these matters.” Lloyd George finished by twisting the knife again. “I say solemnly that the Prime Minister should give an example of sacrifice, because there is nothing which can contribute more to victory in this war than that he should sacrifice the seals of office.”

As can often happen in the Commons, a fractious mood became self-sustaining. Aneurin Bevan accused the deputy speaker of lacking impartiality, while Sir Stafford Cripps compared the government to “the Mad Hatter’s tea party”. The debate dragged itself towards the end until the opposition wind-up, delivered by Labour’s A.V. Alexander, himself a former first lord of the Admiralty. A moment of concern arose as Alexander made his remarks, as he noticed that Churchill, who was due to wind up for the government, was not yet in the chamber. Chamberlain reassured him that Churchill was on his way.

The first lord of the Admiralty began his speech at 10.11 pm. He gave a steady and detailed response to the specific questions which had been asked about the Norway campaign, at first seeming rather low-key by his own florid standards. Perhaps he saw the advantage in playing down his words when Chamberlain had raised the emotional temperature. But it could not last. Churchill prodded at Neil Maclean, Labour MP for Glasgow Govan and a conscientous objector during the First World War.

I dare say the hon. Member does not like that. He skulks in the corner—[Interruption]—What are we quarrelling about? [Hon. Members: "You should withdraw that."] I will not withdraw it.

Maclean rose to object, asking the speaker if “skulk” was an acceptable parliamentary term. Bizarrely, the speaker responded that it depended on whether the word was used accurately, a ruling which left Maclean sceptical. Churchill was growing exasperated. “All day long we have had abuse, and now hon. Members opposite will not even listen.”

He was scathing of the Labour Party’s decision to divide the House. “It seems to me that the House will be absolutely wrong to take such a grave decision in such a precipitate manner, and after such a little notice.” But he ended by appealed for unity and good humour, finally finding his rhetorical pace.

On the contrary, I say, let pre-war feuds die; let personal quarrels be forgotten, and let us keep our hatreds for the common enemy. Let party interest be ignored, let all our energies be harnessed, let the whole ability and forces of the nation be hurled into the struggle, and let all the strong horses be pulling on the collar. At no time in the last war were we in greater peril than we are now, and I urge the House strongly to deal with these matters not in a precipitate vote, ill debated and on a widely discursive field, but in grave time and due time in accordance with the dignity of Parliament.

At 11.00 pm, the speaker put the question, that this House do now adjourn. The effect of the vote was not important—Members were not really dividing on whether they should conclude their business or not—but it was understood that to vote Aye was to support the government and the prime minister, while to vote No was to withdraw one’s confidence from the administration. It is worth rehearsing some numbers. In a House of 615 Members, the government’s notional majority was 213, and it has been estimated that 550 MPs were present (though not all voted in the end).

The government was collectively worried. The whips had seen how the mood was changing in the House throughout the second day, and they knew that they had to achieve one of two things: persuade government backbenchers to remain loyal when it came time to vote, or find some way to persuade the Labour Party to join the coalition. In pursuit of this second goal, the prime minister had despatched his PPS, Lord Dunglass (later Sir Alec Douglas-Home), to tour the Parliamentary Estate and make concessions: he was offering the dismissal of Sir John Simon, the chancellor of the exchequer, and Sir Samuel Hoare, the air secretary, if that would make joining the government acceptable to the opposition. Simon and Hoare were among the most loyal and identifiable Municheers so they seemed like a satisfying burnt offering.

One of Dunglass’s encounters, with Paul Emrys-Evans (Con, South Derbyshire), gives us a useful summary of the unhappiness simmering on the backbenches. Emrys-Evans argued that he was not only unable to support the government, but not even able simply to abstain: things had gone too far. MPs were “thoroughly dissatisfied” with Simon and Hoare, but their sacrifice would not be sufficient. Sir Horace Wilson, the head of the Home Civil Service, was guilty of “intolerable influence in politics and evil influence on policy”. The whips had adopted a “disastrous” attitude to dissent, with far too strong a concentration on discipline and obedience. Most worryingly of all, Emrys-Evans felt that Chamberlain did not have “the right temperament” to lead a government in wartime.

There was another underlying issue which stemmed from Chamberlain, ultimately, but for which Margesson must bear some of the blame. Emrys-Evans was a veteran malcontent, and had complained to Margesson’s deputy, Captain James Stuart, two months earlier that “the whips are just as busy… they seem to enjoy keep up antagonism against the opposition, and indeed against those of us on our own side who have not seen eye to eye with them in the past”.

There was still a degree of cautious optimism. Although Chamberlain was prepared to throw almost any minister overboard to preserve his leadership, he and Margesson were persuading themselves that winning by a respectable margin—no-one could quite identify how large or small that would be—added to a few concessions on the shape of the government would be enough to escape this temporary danger. Were they refusing to face reality? It is hard to judge without foreknowledge of what was to happen. They had one of the biggest majorities in party political history, and Margesson had navigated them through some difficult waters with regard to appeasement before. Why was this to be any different?

The division did not take long—13 minutes, average at best, perhaps even slightly less than usual (informally one allots a quarter of an hour for each vote). When the tellers approached the table of the House, it was no surprise that the government had won. Only the most wild and optimistic of Chamberlain’s critics could have imagined that a majority of 281 would be overturned. But when Margesson, acting as one of the tellers, handed the division slip, on which the results were written, to the clerk, it must have been seen by MPs on the opposition side, as a strange howl went up from Labour Members. Then Margesson declaimed the results: “The Ayes to the right, 281. The Noes to the left, 200.”

The government had won, but the majority had dwindled—in relative terms—to just 81. To break that down, 41 MPs who usually supported the coalition had voted with the opposition instead, while around 60 Conservative MPs had deliberately abstained (it is not really possible to demonstrate an “active” abstention, except by voting in both lobbies, which is deprecated). That was a catastrophic result and laid bare in plain numbers for all to see how many of his MPs no longer felt that Chamberlain should lead them through the war. It was noticeable, too, that almost every Member in uniform had voted no.

It was, though, not entirely clear what was to happen next. Chamberlain thought he would be able to convince the opposition to join the governing coalition, and the succession of Churchill was by no means a done deal: he was still hugely unpopular with some parts of the Left: they remembered his harsh stance on Indian self-government and his decision, as home secretary, to deploy soldiers to break the striking workers in Tonypandy in 1910-11. Moreover he was 65, only a little younger than Chamberlain. His judgement was widely distrusted, and this had been fed constantly through out his career, whether his repeated changes between parties (“re-ratting”) or his appearance in person, in silk top hat and fur-collared overcoat, at the Sidney Street siege in the East End in 1911.

That night, the scenes in the House were pandaemoniac. The opposition and rebellious Conservatives began shouting “Resign!” and “Go! Go!” Chamberlain, white as chalk, did not stay to bear their anger, and slipped out of the chamber almost straight away. Meanwhile MPs loyal to him were yelling “Quislings!” and “Rats!” at the rebels. Colonel Wedgwood began to sing “Rule, Britannia!”, with which Harold Macmillan quickly joined in. While it was true that nothing positive had been decided, nor perhaps anything at all, some anti-Chamberlain MPs thought the prime minister was doomed. His sharp partisanship, his misjudgement of Hitler and his patronising behaviour of the previous two days combined with obvious military setbacks and made him, to them, unacceptable.

The chief whip was furious. One rebel was John Profumo, voting in his first division after having been elected Conservative MP for Kettering at a by-election. He was 25, a Harrovian like Margesson, and was a serving officer in the Royal Armoured Corps. After his decision not to support the government in the Norway debate, he received a savagely angry note from Margesson. It read “I can tell you this, you utterly contemptible little shit. On every morning that you wake up for the rest of your life you will be ashamed of what you did last night.” The chief whip could not have anticipated that later events in Profumo’s life would overshadow his vote on Norway.

Margesson was at the prime minister’s elbow as the crisis unravelled with speed. The day after the Commons division, Thursday 9 May, Chamberlain, having accepted that something had to change, tried one last time to entice the Labour Party into a coalition. This time he was raising the stakes: if they made his departure from Downing Street a condition of joining, and he was required to serve in cabinet under an alternative premier, he was willing to accept that. Nevertheless, over the course of the day, he seems still to have entertained the idea that Labour might yet concede to his retaining the post of prime minister, and while—if only in his mind—that possibility existed, he pursued it with the grim determination he brought to every task.

The inclusion of the Labour Party was now the overriding priority. It is not quite clear 80 years on why this was so pressing: the government had 429 MPs, leaving a combined opposition (plus the speaker and deputies) of only 186. Even in the turbulent circumstances of the previous night’s debate, the government had come nowhere close to numerical defeat. But all the major players seem to have thought that there was something psychologically and morally totemic about all parties in the Commons being included in the government. Even Chamberlain had come to that conclusion. Indeed, the King had already offered to speak to Attlee to impress on him the importance which was universally attached to this.

Chamberlain probably first met at 10 Downing Street with the foreign secretary, Viscount Halifax (although all accounts of the days meetings vary in some details). The “Holy Fox”, as Churchill nicknamed him, is one of the most misunderstood figures of the inter-war era. Prima facie, he seems a reserved, old-fashioned figure: he was a High Church Anglican from an old Yorkshire family and a devoted huntsman (despite being born with a malformed left arm and no left hand). Halifax was a mediocre pupil but flourished at university, winning a first-class degree at Christ Church, Oxford, then a prize fellowship at All Souls. Almost inevitably he was elected to the House of Commons at 28 for Ripon and ploughed a reactionary if unremarkable furrow.

It was easy to characterise Halifax as a run-of-the-mill aristocrat pursuing politics as a rather sigh-inducing performance of noblesse oblige. He was not given ministerial office until 1921, when he joined the Colonial Office as Churchill’s number two, but after that he rose quickly: cabinet minister by 1922, a heftier portfolio in 1924 and then, in 1925, he was appointed viceroy of India. That was the turning point of his career. When he returned to Westminster in 1931, he was only 50, but, although he had moved to the House of Lords (he would succeed to his father’s titles in 1934), he was now a major figure in the Conservative Party and a close ally of Baldwin. He was offered the Foreign Office on the formation of the National government, declining because he knew he would be opposed by some factions, but when Eden resigned in 1938, Halifax was the obvious choice to replace him.

By 1940, then, he was a well established foreign secretary who carried weight and respect. Inevitably he had been cast as the prime minister’s dutiful apprentice in international relations, as Chamberlain desperately tried to keep the peace in Europe, but that masked Halifax’s toughness and cunning. In India he had spent a great deal of his time negotiating with the leading advocates of independence and had been able to season his considerable intellect with hard-won experience. He was loyal to the prime minister but one historian described him as “pragmatic and contingent, not convinced” by appeasement. Finally, and importantly, he had for some years been seen as the most likely heir if Chamberlain were to leave Downing Street for any reason. As one magazine reported breathlessly in 1939, Halifax “possesses that grandezza del animo to which men respond when their true self is stirred”. He was a man the people would trust with the highest office.

When they met in Downing Street on 9 May, Chamberlain told Halifax that if he were forced to step down, then his firm recommendation would be that Halifax should replace him. Importantly, he was entirely acceptable to the Labour Party, despite being a peer, and was a friendly with the King and Queen, who would have welcomed him as prime minister. Chamberlain seemed, therefore, now to have a plan A and a plan B: to convince the opposition to endorse his own continuation in office, with some judicious culling of unpopular ministers; or, failing which, to advise the King to send for Halifax, and perhaps take a position in the reshaped cabinet himself.

Chamberlain and Halifax met again later that day, joined by Churchill and Margesson. They all knew what was at stake and what the options were: but each had his won agenda and his own preferences. Attlee and Greenwood joined to discuss the Labour Party’s feelings. As it happened, the party’s National Executive Committee was meeting in Bournemouth, and the leader and deputy leader could not make a decision without reference to them. They promised to send a message and have the opinion of the NEC returned to them; Attlee would pass this on by telephone the next day. It was agreed that two questions should be put to the NEC. First, would the Labour Party join the government under Chamberlain? Second, if not, would they join under another leader? Attlee claimed later that he gave his opinion, pending a definitive answer, that the party would not accept Churchill. He and Greenwood left to send their message.

Four now remained: Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill and Margesson. Again, no two accounts of the meeting tally in every respect. But there is a broad consensus that Chamberlain may have made some remark indicating his first choice to be Halifax. Churchill (uncharacteristically) said nothing, and the ensuing silence prompted the foreign secretary to say after a pause that it would be difficult for him to lead a wartime government from the House of Lords, and that therefore he did not think he should succeed. Maybe Churchill’s silence was tactical. Maybe he was unsure how to proceed. Whatever was really said in that meeting, the outcome was certain: Chamberlain would recommend that the King send for Churchill, if the Labour Party declined to serve under him.

Halifax recorded his thoughts of 9 May in his diary, writing it up the following day. It is impossible to tell, of course, whether this reflects his true feelings, or if he was already preparing his narrative of the events.

I had no doubt at all in my own mind that for me to succeed him would create a quite impossible situation. Apart altogether from Churchill’s qualities as compared with my own at this particular juncture, what would in fact be my position? Churchill would be running Defence, and in this connexion one could not but remember the relationship between Asquith and Lloyd George had broken down in the first war... I should speedily become a more or less honorary Prime Minister, living in a kind of twilight just outside the things that really mattered.

There was some truth in this analysis. However, there had already been discussions about the legislative technicalities of putting Halifax’s peerages into abeyance, allowing him to stand for election to the House of Commons (where he had sat for 15 years before going to India). So this may not be the whole reason for his reluctance. It is also not entirely clear that his self-deprecation and preference for Churchill on the grounds of personality were wholly sincere. (I shall examine Halifax’s decision not to press his claim for the premiership in a separate essay.)

In any event, Halifax had let the finger of fate move on. The next day, after the war cabinet had met twice, Chamberlain received a telephone call at 4.45 pm from Attlee. The Labour leader told him that the party’s NEC would not agree to serve under Chamberlain; but they were prepared to enter a new government with a new prime minister.

That decided the matter. Chamberlain had no option but to resign, and, given the discussions in Downing Street the day before, he was now obliged (more or less) to advise the King to send for Churchill. The only way that outcome would be frustrated would be if the King did not ask for Chamberlain’s advice; while the sovereign is obliged by constitutional precedent to accept his premier’s advice, he always retains the right, in extremis, not to ask for it. But George VI was too wise and respectful of traditions and practices to do that. There is no doubt that the King would have preferred the foreign secretary. They were good friends, and George had even given Halifax a key to the Buckingham Palace gardens. By contrast, Churchill had been almost the only senior politician to support George’s elder brother, Edward VIII, in his desire to marry the American divorcée Wallis Simpson while also remaining on the throne. That scandal had caused deep rifts in the Royal Family and Churchill was tainted by association, especially in the eyes of the Queen.

Where did this leave Margesson? He had a friendly and cordial relationship with Churchill, despite the latter’s troublesome reputation as a backbencher. Nevertheless he would not have the same close connection as he had enjoyed with Chamberlain, and he could not by any means be sure he would be retained as chief whip. Unusually, Margesson had exhibited little ambition for full ministerial office, though it must have been offered to him during his stint as chief. He seems to have relished the duties and atmosphere of the whips’ office, and he knew he was an effective operator. Yet he was only 49, and was in the final throes of a divorce from his wife Frances. (He took a room at the Carlton Club; when the club was bombed in October, the chief whip was left temporarily homeless and was reduced to sleeping on a makeshift bed in the underground Cabinet Annexe.)

Churchill seems to have realised that he needed Margesson. He had to reconstruct the government in a way which balanced satisfying those who had rebelled with some prominent Municheer scalps while remembering that the majority of the parliamentary party had remained loyal to Chamberlain. It was also significant that Chamberlain, having resigned his office as prime minister, remained leader of the Conservative Party. There was no mechanism to force him out of that post, but it was more textured than that. Churchill must at least have suspected what Margesson knew, which was that the new prime minister was regarded with scepticism by many Conservative MPs. Churchill had, after all, spent the previous decade kicking against the pricks of party policy across a range of issues. He was, anyway, unreliable: he had begun his Commons career as a Conservative but had defected to the Liberals after only four years, had become a distinctly progressive figure for a while, and had only hauled himself back on board the Conservative ship, and tortuously, in the early 1920s. Those with especially vengeful memories would have recalled Churchill’s involvement in the negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, and would have reflected on why it was that the Conservative Party had added the word “Unionist” to its name in 1912.

Chamberlain informed the war cabinet of his resignation in the morning of Friday 10 May. At the last minute, he tried to escape his fate: because it was in the early hours of that morning that the German armed forces burst across the border into the Netherlands and Belgium. This was, he argued, hardly the time for a change of leader, but it was the Labour Party which decided the matter, confirming that they would not under any circumstances come into the coalition with Chamberlain as prime minister. The outgoing premier broadcast to the nation on the BBC at 9.00 pm, and Churchill invited Attlee and Greenwood to visit him at Admiralty House so that they could begin to construct a new government. He promised them that Labour would be offered more than a third of ministerial positions, something of an overrepresentation if one looked at the strict parliamentary arithmetic, and that these would include some major positions. They met until well into the morning of Saturday 11 May.

Margesson was not invited to this initial meeting, and that was significant. Admittedly, Churchill, Attlee and Greenwood were only at that stage intending to appoint a new, slimmed-down war cabinet. On junior positions, Churchill would, as Chamberlain had done, need Margesson’s help: it was simply impossible that he would know anything about the majority of candidates for office, whereas there was always a government whip on the front bench with a notebook, recording how ministers performed, which backbenchers were good or supportive or interesting, and who the troublemakers were.

The creation of a small war cabinet of ministers largely free from departmental responsibilities had been one of the principal demands to emerge from the Norway debate. And it was eerily reminiscent of the transition from Asquith to Lloyd George in the last war, although Churchill had watched that episode from the backbenches, with a dynamic prime minister succeeding a more lacklustre one, and a small, focused ministerial group replacing a larger one in the name of efficiency.

Like the war cabinet which his friend Lloyd George had assembled, Churchill’s comprised just five members, Chamberlain’s having numbered nine. Churchill, of course, was prime minister and leader of the House of Commons, and gave himself the additional new title of minister of defence: this brought ministerial oversight of the Chiefs of Staff Committee and military issues in general. Chamberlain, to the chagrin of the Labour Party, remained in the team, as lord president of the Council (and Conservative leader). His original intention had been to make Chamberlain chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the Commons, but this Labour would not wear, so he was given the non-departmental sinecure instead. In fact, this office would give him substantial influence. He chaired the Lord President’s Committee, which had a coordinating role over home and economic affairs as well as a range of social issues, and chaired the war cabinet in Churchill’s absence.

Attlee and Greenwood were given non-departmental roles too: Attlee, as leader of the Labour Party, became lord privy seal, the more junior sinecure in the cabinet, while Greenwood, his deputy leader, became minister without portfolio. The fifth and final member of the war cabinet was Halifax, who remained foreign secretary, the only departmental head to be included.

It had been one of the major complaints against Margesson in the Chamberlain days that he had had too much control over government appointments, especially at the more junior level. He tended, his critics grumbled, to favour dull but reliably loyal MPs who often turned out to be adequate at best for their ministerial duties. Like many of the charges laid against Margesson, it was slightly unfair: the chief whip will always have considerable input into patronage, and this will be more true at the junior level where the prime minister would simply be flying blind. But it was perhaps the case that Chamberlain had surrendered the initiative with relief, and that Margesson had taken it on a little too readily.

In any event, Churchill grasped his still-delicate position with regard to the Conservative Party, and gave Margesson almost completely free rein over the junior appointments. The two men met together for many hours on 11 and 12 May, putting together a full set of ministers, accommodating a cohort of MPs from the Labour and Liberal parties which had now joined the coalition. Some of these were or would become significant figures. A.V. Alexander returned to his (and Churchill’s) old post of first lord of the Admiralty; the Liberal leader Sir Archibald Sinclair, who had been Churchill’s second-in-command on the Western Front in 1916, took over the Air Ministry; Labour’s Hugh Dalton, with his booming voice and his boundless self-satisfaction, became minister of economic warfare (with the Liberal Dingle Foot, brother of Michael, as his junior minister); while the rugged and effective Ernest Bevin, general secretary of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, was named minister of labour and national service, though not even in Parliament (a seat in the Commons was rapidly found for him).

Some of Margesson’s advice was surprisingly frank. At one point he indicated a name written down for a ministerial job and said “Strike him out, he’s no good at all.” There was a degree of bafflement, as the MP was a veteran of Chamberlain’s government: why had Margesson appointed him in the first place? “Oh well,” Margesson replied honestly, “he was useful at the time.”

All of this meant, of course, that Churchill had retained Margesson as chief whip. Some expressed surprise and dismay, regarding Margesson as the Chamberlainite sans pareil and therefore the epitome of the old régime, but there is no evidence that Churchill even considered bringing in a new chief whip. He and Margesson had a friendly relationship, and, with the cheerful goodwill of which he was sometimes capable, the new prime minister recognised that he needed the diligence and loyalty with which Margesson had previous served Chamberlain. In fact, the nervousness lay in the Whips’ Office, fearful of a purge. Margesson’s deputy, the dashing Scottish nobleman James Stuart, told a fellow MP that he would get out of the office if he could, describing the new government as “the whole box of tricks”.

In fact, there was a body of opinion which maintained that Margesson had sold out and betrayed his old master. Some wit coined the nickname “the parachutist” for the chief whip after Churchill took over as prime minister, and Margesson found himself cold-shouldered by Chamberlainite ultras in the social spaces of the Commons. But both sides of the argument were allowing emotion, whether long-simmering resentment or newfound and angry surprise, to cloud their judgement. Margesson’s mission had been since 1931 to maintain discipline among government backbenchers and to deliver divisions and legislation for his ministerial colleagues. He had been ruthless but effective in doing that, and when the Commons, in a nebulously collective way, decided that it should now be Churchill, not Chamberlain, who led that government, Margesson continued doing the job he had always done.

One Member seemed to have. a particular vendetta against the chief whip. Vyvyan Adams, the MP for Leeds West, who had been a consistent opponent of Chamberlain’s foreign policy, had protested at the involvement of Margesson in the formation of the new government. On 25 July, he asked a question in the Chamber: “whether, to effect economy, he will now limit the tenure of the Parliamentary Secretaryship to the Treasury to the hon. Member most recently appointed to that office?” That was, of course, Margesson’s official title. Attlee, answering for Churchill, replied with a crisp “No”.

Adams’s supplementary question was even more pointed.

Can my right hon. Friend say how it comes about that the right hon. and gallant Gentleman the Member for Rugby [Margesson] is still allowed to flourish like a green bay-tree; and may I also ask how can that right hon. and gallant Gentleman possibly require support for a Government whose coming into existence he did his best to prevent?