Humanism: it's not what you might think

With a sparkling new history of humanism on the shelves, we need to pause and understand exactly what we mean by the term so highly elevated by modernity

I’ve been thinking about humanism a lot recently. Now, I’m aware that, even by my high standards, that’s an opening sentence of considerable pretension and unbearableness, but stay with me. It’s not quite as dreadful as it sounds: my academic background is early modern history, my anchor the middle Tudors and my beloved and inspiring history master at school was devoted to Erasmus, perhaps the greatest humanist intellectual of them all. So this is a world I’ve slipped in and out of for 30 years and more.

One spur to all of this has been reading reviews, most recently by fellow former Commons clerk Philip Hensher in this week’s edition of The Spectator, of a new book by Sarah Bakewell entitled Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Thinking, Enquiry and Hope. On the whole, Philip liked the book. There were elements missing, he felt, and some issues were dealt with in less depth than he would have liked, but he concluded that it was “a jolly and readable skate through a large swathe of philosophical thought and practical endeavour”, which I would certainly accept with contentment if I had tried to pack seven centuries of humanism into 464 pages. It seems to be a common judgement. Mark Oppenheimer in The Washington Post called it “a terrific invitation to argument, to conversation, to all the fun people make together, on their own”. The former archbishop of Canterbury Lord Williams of Oystermouth, no mean scholar of thought (he was appointed Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at Oxford when he was 36), reviewed the book for The New Statesman and found it a “superbly readable, witty and attractive survey of the history of ‘humanism’”. And the novelist and science writer Simon Ings, writing in The Daily Telegraph, judged it an “epic, spine-tingling, seamless account” detailing “the Western mind’s 700-year effort to ignore priestly and sectarian blarney so as to nurture its own voice, its own conscience, and its own good”.

The other thought which flared in my brain was the ongoing Twitter sniping at Professor Alice Roberts, the exceptionally well qualified author and anthropologist who holds a chair in the Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham. (I say “well qualified” as she is a qualified medical doctor with an intercalated degree in anatomy, has a doctorate in palaeopathology, has conducted research into osteoarchaeology and has taught embryology. That’s always struck me as a dazzling array of fields.) I enjoy her television work and I think she’s an enthusiastic and effective communicator, even if her inextinguishable perkiness can sometimes be too much for my occasionally dyspeptic soul. But she—perhaps unwittingly—vaulted over the parapet of the trench into no man’s land when she took on the presidency of Humanists UK (formerly the British Humanist Association) in January 2019.

Professor Roberts attracted the ire of some believers for what they perceived as an overly aggressive or superior tone towards men and women of faith. An early critic was the inevitable Peter Hitchens, who attacked her supposed hypocrisy for sending her daughter to a church school and concluded she was “just an annoying zealot”; if I were a prominent humanist, I might regard an assault by Hitchens Minor as a badge of honour or at least a good start, but that is by the by. Theo Hobson took her to task for the very nature of humanism itself, suggesting it lacked “any real coherence” and wondered aloud if Roberts neglected the contribution of Christianity to her own world view. And the amiable Fr Marcus Walker, rector of Great St Bartholomew’s and a genial but scholarly public intellectual, felt that Roberts, like many humanists, unfairly presumed bad faith (excuse the pun) in her philosophical opponents, a habit which damaged the whole superstructure of debate.

I don’t want to be drawn here into the debate between Roberts and her organisation (she was succeeded as president by the geneticist and writer Dr Adam Rutherford in June last year). I don’t think I have much to add to it, but I was aware of its overspill on to the timelines of Twitter, so Bakewell’s book led me on to recall the conflict. I should say at this point, however, that I am not a religious person. I was brought up in a middle-class Establishment atmosphere no more permeated by the Church of England than any other, and my academic studies (and many friendships) have bathed me in the history and spirituality of the Roman Catholic Church; I have never passionately believed in a supernatural being but for a long time was a comfortably imprecise agnostic. Not so very long ago, though, I realised that a little intellectual precision and honesty would show me that I was, in fact, an atheist, that there was nothing so very forbidding in that, and that in fact it offered a degree of solace and acceptance of the world which I had not anticipated. However, I am absolutely not a militant atheist, and I regard such unbelievers with irritation and disdain. So long as it neither breaks my back nor picks my pocket, I am very comfortable with people having faith. By all means deprive yourself of things you enjoy for Lent, but I would rather you didn’t blow up the public transport I use frequently.

This does not mean I am a humanist. I know and love some people who are, and that is fine, but the movement, if that is the right word, often strikes me as a little pompous and, more curiously to me, seems to crave the kind of ritual and ceremony which theistic religion had always enjoyed. So there are humanist celebrants, humanist ceremonies, humanist texts. This strikes me as an awkward halfway house: religious pomp and display has an obvious genesis and an obvious role, and it is very easy to imagine similar ceremony which is free from religion. But humanism’s attempt to inject a kind of credo, a morality, a sort of godless faith sits uneasily with me. For that reason I’ve never been drawn to the humanist part of the forest.

The reason that humanism has been flitting round my head like a determined moth is that I worry the term is being used both freely and inaccurately. I think any serious thinker will understand that the quasi-religious definition of humanism which sets it up, as modern humanists do, as an alternative to theism is a specific and rather niche one. Humanists UK talk about a creed for non-religious people who “trust to the scientific method, evidence, and reason to discover truths about the universe”, and whose decision-making looks to the human experience for its ethical basis. They are careful to emphasise the logical and rational nature of their belief system, relying on “reason, empathy, and a concern for human beings and other sentient animals”. They also reject notions of an afterlife or any kind of deferred reward for good works done in this life. This is, of course, to maximise the effort devoted to human wellbeing and happiness.

I fully understand why people who do subscribe to a religious faith can find this definition grating. It is easy to infer from it that humanism is in some ways superior to faith, with a stronger intellectual basis and a more accurate grasp of the reality of the world around us. Indeed, there are humanists who would not dissent from this notion. Absent the sense of superiority, it is a blameless and understandable code of thought and behaviour, and, stripped to its essentials, it is not so far from the sort of belief system to which I adhere. The late Christopher Hitchens, whom I admired and liked greatly even if many of his beliefs were almost opposite to mine, had a nicely pointed spin on it. When he debated with proponents of religion, as he did often, they would often pray in aid the good and charitable deeds done by religious figures. His challenge was to name a single instance of kindness, valour, generosity or protection which could not have been carried out by an unbeliever. It is a very difficult challenge to answer. We may all be able to think of saintly figures of many faiths, and they may well have been motivated by a deep sense of their religious conviction, but I cannot think of a single one who would have been unable to perform the same act of kindness or charity in the absence of his or her faith.

The reason I am uneasy and my historian’s sensibilities are pricked is that the definition above would have been unfamiliar and largely unintelligible to the first scholars and thinkers to bear the humanist label. That it was in opposition to religious belief, rejected the idea of life after death or focused wholly on the experience of the individual human being was simply not true, and dealt in concepts, like atheism, which were at best theoretical to late mediaeval intellectuals.

When I was a doctoral student at the University of St Andrews, many years ago, I had the opportunity to help teach a history module for second-year students, which covered British and European history from 1450 to 1815. I particularly relished the challenge of the first semester, since that covered the early modern period (1450-1660) which was and is the centre of my interest and research. Most of the students I taught—especially those from the US—had never studied the period before, and, quite understandably, had to overcome some hurdles in seeing into the very different mindset and mental world of people living in the 16th century. Among those hurdles, and which are relevant to the consideration of humanism, were the universality of religion and the all-pervading nature of religious belief.

Atheism is not a new concept. It had existed at least as early as the 6th century BC in south Asia and the Far East, with Buddhism, Jainism and some Hindu sects rejecting the notion of a central creator deity and Taoism in China lacking an omnipotent god and instead being based on the natural order of the universe. In the classical Mediterranean world, with a pantheon of gods who differed from the Abrahamic idea of an all-powerful deity, atheism was recognised and regarded as a capital offence, but it was not so much the rejection of belief in the existence of the pantheon, more the subversion of the form of publicly endorsed devotion, what would become more usually regarded in Christianity as heresy or heterodoxy.

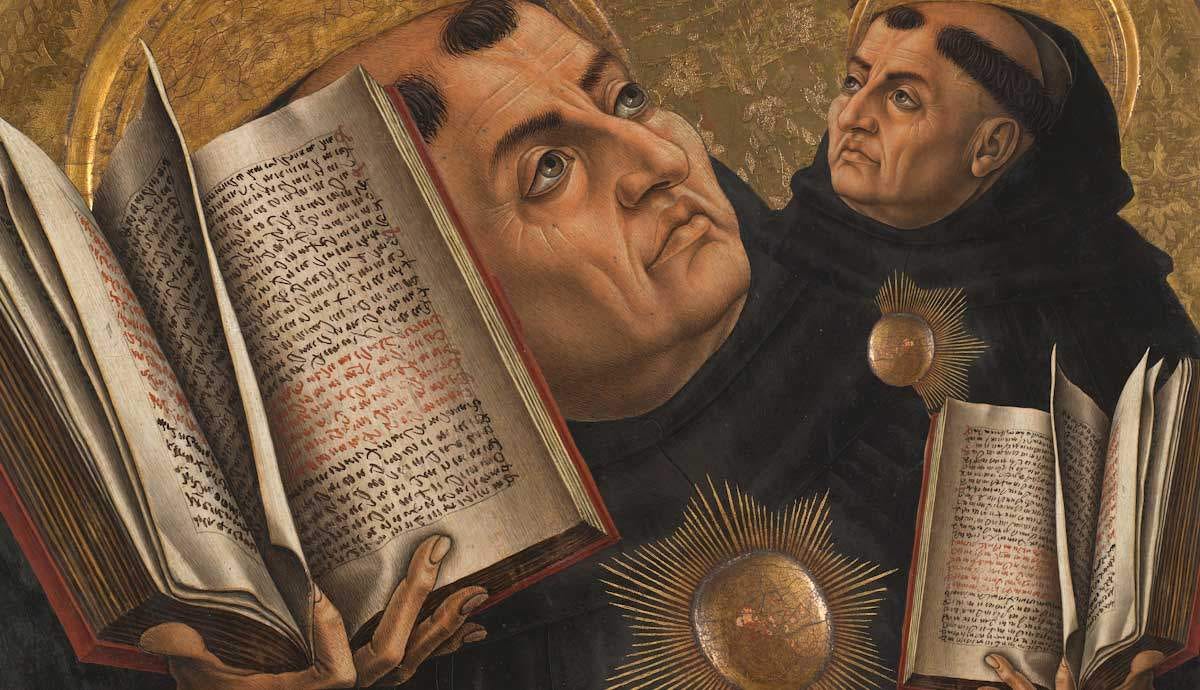

Although some of the most eminent theologians of the Middle Ages, like St Anselm of Canterbury and St Thomas Aquinas, the “Angelic Doctor”, produced proofs of the existence of God which have been taken to imply the currency of atheism, they were in truth more specifically targeted at different notions of belief and heterodox theories, such as that the existence of God was innately known to man without any external support or that no further reflection than instinct was needed to approach the divine. (If you want to dig into this more, St Thomas deals with the existence of God in Question 2 of the First Part of his Summa Theologica of 1265 to 1273. Even if it doesn’t persuade you, it’s an excellent example of the mediaeval Christian form of scholarship, teaching and argumentation.)

There are, of course, instances of lax adherence to religious observance in mediaeval Europe. It is obvious from the proliferation of sermons and injunctions to attend church that there were people who regarded the practice of their faith very lightly and may well have worshipped according to rote when they were compelled. But it is too big a leap from scepticism or lack of enthusiasm to the intellectually coherent proposition that God did not exist. It’s also worth remembering that the duties of mediaeval Christianity were not desperately onerous. Attendance at Mass was expected on Sundays and for important religious feasts, of which there were 40 or 50 a year, so most people would go to church once or twice a week. But this was not compulsory and it was understood that the rigours of life sometimes took precedence. Children were not generally expected to attend once they were old enough to be left alone, until they reached puberty.

The non-negotiable obligation was participation in Mass on Easter Sunday. Everyone had to take communion at that service (though they would only receive the bread, which was the body of Christ, not the wine, the blood of Christ), and in order to be given the Eucharist they would have to have confessed their sins and be shriven, that is, be assigned penance for one’s sins and granted absolution by the priest. The congregation would not normally have received the Eucharist at other services during the year, though they would have adored the Host when the priest (who always took communion in both kinds, bread and wine) elevated it at the central point of the mass.

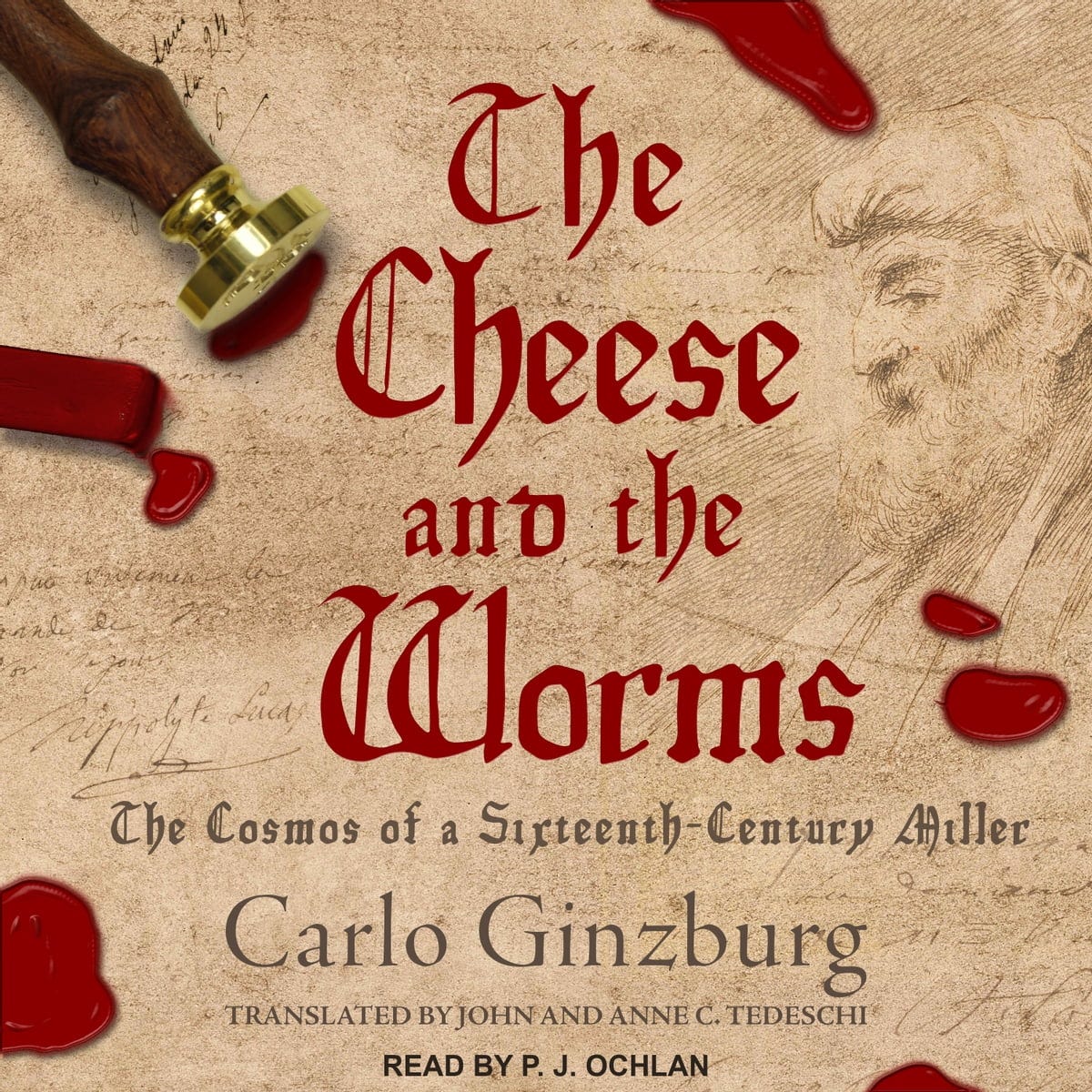

This rhythm of collective and communal obligation made the development of a determined and performative form of atheism difficult. We know that, because the critical parts of the Mass were in Latin rather than the vernacular, and the clergy were not always as literate and learned as they should have been, the detailed grasp of Catholic theology among the laity was often imperfect and sometimes consciously heterodox. Carlo Ginzburg’s brilliant 1980 microhistory of Domenico Scandella, known as Menocchio, The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller, unpicks all sorts of unusual beliefs and denials in the person of a miller in the Venetian village of Montereale.

Interrogated by the Inquisition in 1584, Menocchio, having been isolated in his small community, poured out his curious or dangerous notions to his examiners. He disapproved of the use of Latin for worship and doubted the precise veracity of Scripture, while looking with less scepticism than the Church on the gospels declared apocryphal. Furthermore, he rejected imagery, ceremonies, the seven sacraments, the significance of saints’ days, and a mediating priesthood, believing that laymen had a right to preach. He also attacked the wealth and economic power of the Church. This was quite the heretical catalogue. He even came close to articulating a code which modern humanists would recognise and welcome, telling the inquisitors “We should be concerned about helping each other while we are still in this world” rather than wasting time on intercessory prayer.

Perhaps humanists are cheering. But Menocchio was not an atheist. However much of the Church’s ritual and theology he rejected, he still believed, almost reflexively, in a divine being, or perhaps more than one. There was simply not path for him to follow, nor any inclination, to reject the supernatural altogether and aver that this life was all there was and it was irrational to think otherwise. The early modern Christian world had no satisfactory intellectual mechanism for imagining a world without the presence, if not necessarily influence, of the divine, and this might very well have been because it had never sought one.

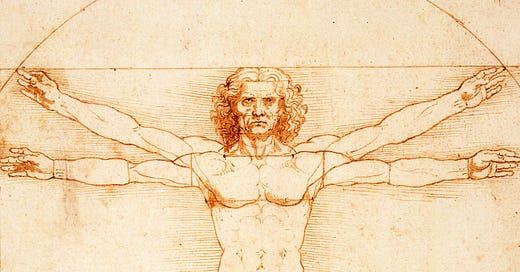

The reason, if you are wondering, that I make such heavy weather of this issue is that it directly affects the way we identify and define the beginnings of “humanism”. The Romans had dealt freely and comfortably with the notion of “humanitas”, a notion they took to fuse the Greek ideas of philanthropia (a love for the essence of being human) and paideia (education), and it was lauded as a key virtue by Quintilian, Seneca, Cicero and a slew of other writers and public figures, a badge pinned on the chest of Pompey, Caesar and Crassus among others. When a major revival of classical learning and mores began in 14th-century Europe, taking its cue from the first prophets of the Renaissance in Tuscany, Veneto and Avignon, men like Lovato Lovati, Ferreto de’ Ferreti and Convenevole da Prato, it looked to the Greek and Roman origins of European culture as a reaction against the accretion and ossification of styles and methods which the mediaeval period had seen develop. It was significant that it would eventually be labelled as the Renaissance, though this would take until the 19th century; but Giorgio Vasari had reached for the word rinascita, “rebirth”, when describing the movement in his The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, the first edition of which appeared in 1550. So there was a consciousness at the time that this was not a movement of innovation but of rediscovery.

All of this matters because humanism was not a rejection of Christianity. Certainly, it was an epochal shift in emphasis. Beginning in the hyper-scholarly and affluent city states of northern Italy, there was an unquenchable thirst for returning to the intellectual life of classical Greece and Rome: these were, of course, pagan texts, written by thinkers who had lived centuries before Christ, but that was not, nor had it ever been, an obstacle for Christian writers. In the second century AD, with the very life of Christ himself only just beyond memory, Christian apologists had found ways to understand classical philosophy as compatible with the new revealed faith and even to treat it as buttressing Christianity. Justin Martyr, for example, born to a Greek family in Samaria around AD 100, argued that Platonism and Stoicism were simply different ways of approaching elements of what was transformed into Christian doctrine; while St Basil the Great, a Greek Cappadocian active in the fourth century AD who was prominent in the defeat of Arianism, drew the analogy between pagan thinkers preceding Christian ones and cloth being prepared before dyeing in order that the colour should be fast.

So the humanist eagerness for classical texts implied no conflict with a Christian identity. But historical narrative thrives on, or is more intelligible through, opposition and antithesis. Simplistic perspectives have, therefore, set up humanism not only as an opposite of Christianity but also of scholasticism, the mediaeval superstructure of learning and critical thought. Scholasticism, growing from the intellectual life of the monasteries and founded on the Categories of Aristotle, was itself concerned with the synthesis of Christian and pre-Christian thought, rediscovering Greek texts which had been lost in their original language in what we may no longer call the Dark Ages (except where they were preserved, curiously, by Irish monastic schools) and absorbing classical wisdom from translations into Arabic via Syriac and then into Latin.

The caricature of scholasticism which developed, not least thanks to the efforts of many humanist scholars, it must be said, was less about the examination and synthesis of ancient philosophy and more about a supposed methodology which grew up over the centuries of the Middle Ages. (Remember the span of time which we are contemplating: the foundations of scholasticism were laid by Boethius in the early 6th century AD and the discipline, if we can use that word, reached its height in the 13th century with St Thomas Aquinas and was still dominant in the universities of western Europe 100 years later.) Renaissance humanists would come to depict scholasticism as rigid and hidebound, focused on legal, logical and rationalistic aspects of scholarship and increasingly inward-looking and self-referential.

The emblem of all that was deficient about scholasticism was the purported theological question, posed mockingly by Protestant thinkers of the 17th century: how many angels can dance on the head of a pin? It was meant as a parody of obsessive, microscopic scrutiny of issues which had no connection to the real world, to the “human condition” which exemplified the humanist approach to learning, and took a direct swipe at the angelology of Aquinas and the Berwickshire Franciscan scholar Duns Scotus. There is no evidence that the exact question was ever considered, although Aquinas’s Summa Theologica did deal with the physicality of angels, for example considering whether several angels could be in one place at the same time. But in the Angelic Doctor’s supple intellectual grip, this was not an abstruse mental exercise. It spoke to the very nature of angels, whether they were corporeal bodies, if their heavenly natures could physically co-exist and to what extent the soul had a specific location in the human body or existed throughout.

What humanists were, for their own reputational reasons, taking aim at was in fact the style of disputation used by the schoolmen. As it had developed over centuries of intense scholarship, it is hardly surprising that that method became stylised, formulaic, perhaps outwardly stiff. But it was wholly unfair to imply that it bespoke an underlying aridity. Indeed, how could it be other? It would be foolish to assume that humanists sprang fully formed from the earth, like the skeleton warriors which grew from the hydra’s teeth sown by Cadmus at the direction of Athene. On the contrary, they came, in the main, from the very schools whose doctors they came to despise and ridicule. Pico della Mirandola had begun his studies in canon law at Bologna, the West’s first university, now around 935 years old, where Petrarch had also been educated; Martin Luther had been trained in the traditional mediaeval trivium of grammar, rhetoric and logic before reading law then theology at Erfurt, and had even taken the tonsure as an Augustinian friar at the convent there; and Desiderius Erasmus, perhaps the greatest humanist scholar of them all, had attended the Sorbonne in Paris, in the 1490s still the Mount Doom of scholastic thought and practice.

In fact we can make no clear nor useful distinction between humanists and orthodox Christians, nor between humanists and scholastics, in the period which bridges the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Humanism was a new approach to understanding the world, man’s place in it and—absolutely crucially—his relationship with God, and it would emerge as a massively influential change of emphasis, but it is not plausibly a discontinuity of the intellectual tradition, much less a tmesis between a world which looked only upwards to the Creator and one which abjured the heavens exclusively in favour of the society of men.

This, then, explained perhaps at greater length than some readers will have been expecting, is the source of my unease at the easy way in which “humanism” is tossed around taxonomically. Consistently with my thesis that we are becoming more careless and ignorant of our past, we are projecting our current understanding of the notion of humanism backwards through time without noticing how far it goes or where the intellectual shellfire lands. This matters. It matters not simply because I am fusser when it comes to meaning and semantics, but because if we do not pay attention we see revolutionary caesuras where there are none and equally assume continuity where it is absent.

Perhaps most of all, we fail to grasp in its totality the extraordinary development of western thought. The transition from the late mediaeval period to the Renaissance and Reformation and then onwards through the Counter-Reformation and onwards to the Enlightenment is not a tournament of football matches in which we must pick our sides; we do not have to cheer on St Thomas More while booing William of Ockham, or pile in behind Cornelius Jansen against slippery and casuistical Jesuits.

(Which being said, I confess to a slight knee-jerk suspicion of Jesuits and those educated by them which is, I’m sure, largely unjustified; that said, see Johnnie Cochran (Loyola Law School), Sir William Cash (Stonyhurst) and Hardeep Singh Kohli (St Aloysius), not to mention the current Holy Father, the fanatically factional and doctrinally unreliable Pope Francis.)

Our intellectual tradition is rich, profound, dazzlingly embroidered and powerfully influential. It has given us the most humbling and weighty thoughts as well as some of the greatest, purest and often most charming delights. Let’s keep it that way, and cherish it. And a good start, I would humbly submit, is to make sure we know what we’re talking about when we consider different strands of philosophy, belief and behaviour. If you begin a journey properly prepared and equipped, it is much more likely to go well, and lead you to your intended destination.

Religion baffles me. Its utterly irrational. Belief in something invisible. But it must fulfill a need because it has survived so long and across all of history and humanity. An explanation of why is I think at its core. I was in a Cathedral on Saturday, it was built starting in 1086, on the site of older Anglo saxon place of worship. It's magnificent almost magical place. It inspires and gladden me whenever I go inside, though I'm agnostic. Maybe because three great acts of life are inextricably linked to such places, birth, marriage and death. Service to society and country are recorded too by the flags, colours, plaques and stones all around its walls. The Grave of a King can be seen and touched. To an open and receptive mind such places link the one to the many and also across time. It's a very impressive gig. Light a candle for your mum. Buy a jar of honey to help poor kids. Listen to an organ playing. Watch the shadows play in the Great East window made 750 years ago. Humanism despite its many virtues has a long way to go to equal all that.